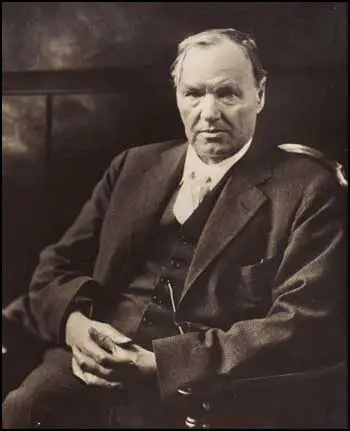

Clarence Darrow

Clarence Darrow was born in Kinsman, Ohio, on 18th April, 1857. His father had originally trained as a Unitarian minister, but lost his faith and Clarence was brought up as an agnostic. An opponent of slavery, Darrow brought up his son as a supporter of reformist politicians such as Horace Greeley and Samuel Tilden. "From my youth I was always interested in political questions. My father, like many others in northern Ohio, had early come under the spell of Horace Greeley... I was fifteen years old when Horace Greeley ran for the presidency. My father was an enthusiastic supporter of Greeley and I joined with him; and well do I remember the gloom and despair that clouded our home when we received the news of his defeat."

After an education at Allegheny College and the University of Michigan Law School, Darrow became a member of the Ohio bar in 1878. For the next nine years he was a typical small-town lawyer. However, in 1887 Darrow moved to Chicago in search of more interesting work. During this period he read the work of radical journalist, Henry George. "During these early years in Chicago I was very much interested in what passes under the name of 'radicalism' and at one time was a pronounced disciple of Henry George. But as I read and pondered about the history of man, as I learned more about the motives that move individuals and communities, I became doubtful of his philosophy. Socialism seemed to me much more logical and profound; Socialism at least recognised that if man was to make a better world it must be through the mutual effort of human units; that it must be by some sort of co-operation that would include all the units of the state. Still, while I was in sympathy with its purposes, I could never find myself agreeing with its methods. I had too little faith in men to want to place myself entirely in the hands of the mass. And I never could convince myself that any theory of Socialism so far elaborated was consistent with individual liberty."

As a young lawyer, Darrow had been impressed by the book Our Penal Machinery and Its Victims by John Peter Altgeld. The two men became close friends and shared a belief that the United States criminal system favoured the rich over the poor. Later Altgeld was elected governor of Illinois and controversially pardoned several men convicted after the Haymarket Bombing.

In 1890 Darrow became the general attorney to the Chicago and North Western Railway. However, during the Pullman Strike Darrow felt sympathy for the trade unions and offered his services to its leaders. Darrow argued in one trial involving union leaders: "Let me tell you, gentlemen, if you destroy the labor unions in this country, you destroy liberty when you strike the blow, and you would leave the poor bound and shackled and helpless to do the bidding of the rich. It would take this country back to the time when there were masters and slaves."

Darrow defended Eugene Debs, president of the American Railway Union, when he was arrested for contempt of court arising from the strike. Although Debs and his fellow trade unionists were convicted, Darrow had established himself as America's leading labour lawyer. Over the next few years Darrow defended several trade union leaders arrested during industrial disputes. Darrow also became involved in the campaign against child labour and capital punishment.

In September 1905, Darrow helped to establish the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Other members included Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Florence Kelley, Jack London, Anna Strunsky, Bertram D. Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, Rose Pastor Stokes and J.G. Phelps Stokes. Its stated purpose was to "throw light on the world-wide movement of industrial democracy known as socialism."

In 1905 William D. Haywood, leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), was charged with taking part in the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho. Steunenberg was much hated by the trade union movement after using federal troops to help break strikes during his period of office. Over a thousand trade unionists and their supporters were rounded up and kept in stockades without trial.

James McParland, from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was called in to investigate the murder. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire. McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named Hayward and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Darrow was employed to defend Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Harry Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry. During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard and were all acquitted.

Harrison Gray Otis, the owner of the Los Angeles Times, was a leading figure in the fight to keep the trade unions out of Los Angeles. This was largely successful but on 1st June, 1910, 1,500 members of the International Union of Bridge and Structural Workers went on strike in an attempt to win a $0.50 an hour minimum wage. Otis, the leader of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association (M&M), managed to raise $350,000 to break the strike. On 15th July, the Los Angeles City Council unanimously enacted an ordinance banning picketing and over the next few days 472 strikers were arrested.

On 1st October, 1910, a bomb exploded by the side of the newspaper building. The bomb was supposed to go off at 4:00 a.m. when the building would have been empty, but the clock timing mechanism was faulty. Instead it went off at 1.07 a.m. when there were 115 people in the building. The dynamite in the suitcase was not enough to destroy the whole building but the bombers were not aware of the presence of natural gas main lines under the building. The blast weakened the second floor and it came down on the office workers below. Fire erupted and spread quickly through the three-story building, killing twenty-one of the people working for the newspaper.

The next day unexploded bombs were found at the homes of Harrison Gray Otis and of F. J. Zeehandelaar, the secretary of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association. The historian, Justin Kaplan, has pointed out: "Harrison Gray Otis accused the unions of waging warfare by murder as well as terror.... In editorials that were echoed and amplified across a country already fearful of class conflict, Otis vowed that the supposed dynamiters, who had committed the 'Crime of the Century,' must surely hang and the labor movement in general."

William J. Burns, the detective who had been highly successful working in San Francisco, was employed to catch the bombers. Otis introduced Burns to Herbert S. Hockin, a member of the union executive who was a paid informer of the (M&M). Information from Hockin resulted in Burns discovering that union member Ortie McManigal had been handling the bombing campaign on orders from John J. McNamara, the secretary-treasurer of the International Union of Bridge and Structural Workers. McManigal was arrested and Burns convinced him that he had enough evidence to get him convicted of the Los Angeles Times bombing. McManigal agreed to tell all he knew in order to secure a lighter prison sentence, and signed a confession implicating McNamara and his brother, James B. McNamara. Other names on the list included Frank M. Ryan, president of the Iron Workers Union. According to Ryan the list named "nearly all those who have served as union officers since 1906."

Some believed that it was another attempt to damage the reputation of the emerging trade union movement. It was argued that Harrison Gray Otis and his agents had framed the McNamaras, the object being to cover up the fact that the explosion had really being caused by leaking gas. Darrow was employed by Samuel Grompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, to defend the McNamara brothers. One of Darrow's assistants was Job Harriman, a former preacher turned lawyer.

On 19th November 1911, Darrow and Lincoln Steffens was asked to meet with Edward Willis Scripps at his Miramar ranch in San Diego. According to Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Darrow arrived at Miramar with the sure prospect of defeat. He had failed, in his own investigations, to breach the evidence against the McNamaras; on his own, he had even turned up fresh evidence against them; and, in desperation, hoping for a hung jury and a mistrial.... Steffens, who had interviewed the McNamaras in their cell that week, asking for permission to write about them on the assumption that they were guilty; he had even talked to them about changing their plea. Darrow, too, was approaching the same stage in his reasoning. It was tragic, he had to agree with the other two, that the case could not be tried on its true issues, not as murder, but as a 'social crime' that was in itself an indictment of a society in which men believed they had to destroy life and property in order to get an hearing."

Scripps suggested that the McNamaras had committed a selfless act of insurgency in the unequal warfare between workers and owners; after all, what weapons did labour have in this warfare except "direct action". The McNamaras were as "guilty" as John Brown had been guilty at Harper's Ferry. Scripps argued that "Workingmen should have the same belligerent rights in labour controversies that nations have in warfare. There had been war between the erectors and the ironworkers; all right, the war is over now; the defeated side should be granted the rights of a belligerent under international law."

Lincoln Steffens agreed with Scripps and suggested that the "only way to avert class struggle was to offer men a vision of society founded on the Golden Rule and on faith in the fundamental goodness of people provided that they were given half a chance to be good". Steffens offered to try and negotiate a settlement out of court. Darrow accepted the offer as he valued Steffens for "his intelligence and tact, and his acquaintance with people on both sides". This involved Steffens persuading the brothers to plead guilty. Steffens later wrote: "I negotiated the exact terms of the settlement. That is to say, I was the medium of communication between the McNamaras and the county authorities". Steffens met with the district attorney, John D. Fredericks. It was agreed the brothers would change their plea to guilty but offer no confession; the state would withdraw its demand for the death penalty, agree to impose only moderate prison terms, and also agree that there would be no further pursuit of other suspects in the case.

Darrow argued in his autobiography, The Story of My Life (1932): "The one reason that made me most anxious to save their lives was my belief that there was never any intention to kill any one. The Times building was not blown up; it was burned down by a fire started by an explosion of dynamite, which was put in the alley that led to the building. In the statement that was made by J. B. McNamara, at the demand of the State's attorney before the plea was entered, he said that he had placed a package containing dynamite in the alley, arranged the contraption for explosion, and went away. This was done to scare the employees of The Times and others working in non-union shops. Unfortunately, the dynamite was deposited near some barrels standing in the alley that happened to contain ink, which was immediately converted into vapor by the explosion, and was scattered through the building, carrying the fire in every direction."

On 5th December, 1911, Judge Walter Bordwell sentenced James B. McNamara to life imprisonment at San Quentin. His brother, John J. McNamara, who could not be directly linked to the Los Angeles bombing, received a 15 year sentence. Bordwell denounced Steffens for his peacemaking efforts as "repellent to just men" and concluded: "The duty of the court in fixing the penalties in these cases would have been unperformed had it been swayed in any degree by the hypocritical policy favoured by Mr. Steffens (who by the way is a professed anarchist) that the judgment of the court should be directed to the promotion of compromise in the controversy between capital and labour." As he left the court James McNamara said to Steffens: "You see, you were wrong, and I was right".

Although Darrow supported Allied involvement in the First World War he represented several people charged with anti-war activities. Darrow was especially critical of the Espionage Act and the way it was used to imprison left-wing trade union activists. However, he refused to support the Russian Revolution and he told Lincoln Steffens that the Bolshevik leaders would "end up like all the rest".

Darrow's liberal views were based on the belief the social and psychological pressures were mainly responsible for an individual's anti-social behaviour. In 1924 he agreed to take the Leopold-Loeb case, where two wealthy students had kidnapped and murdered a young boy. Darrow insisted that his clients plead guilty and then saved them from the death penalty by using expert witnesses to show how Leopold and Loeb were not completely responsible for their actions.

His old friend Lincoln Steffens claimed that "Darrow handles himself as if he were a musical instrument. He has fought the greatest battles of our day and won them. He can't bear to have a client executed. We call him the attorney for the damned, and he says life isn't worth living!" (Darrow had once said that "had I known what life would be like when I was born, I'd have asked God to let me off.")

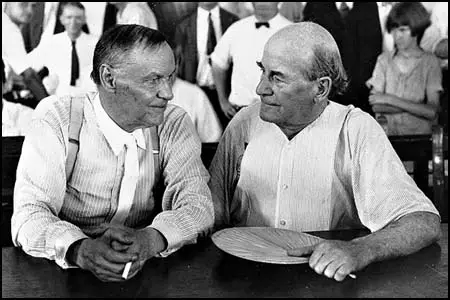

Darrow's most famous case was in 1925 when he defended John T. Scopes, a teacher accused of teaching the evolutionary origin of man, rather than the doctrine of divine creation. His main opponent in the case was the former presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, who believed the literal interpretation of the Bible. Although it is claimed that Darrow outshone Bryan during the Scopes Trial, Scopes was found guilty.

Darrow also played a prominent role in the Sweet Case (1925-26), where he successfully defended a black family who had used violence against a mob trying to expel them from a white area in Detroit. Darrow also worked on the Scottsboro Case, where nine young black men were falsely charged with the rape of two white women on a train.

Ella Winter, the wife of Lincoln Steffens met Charles Darrow for the first time in 1926. She wrote in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "Clarence Darrow was as picturesque as he was fascinating. His huge head dropped sideways, as if too heavy to carry. His face was carved into deep and wonderful lines, his hulking frame hung loosely inside his clothes, and he hunched his head deep into his shoulders when he made a point, so that you saw no neck at all.... Darrow, craggy, broad-shouldered, slow-speaking and humorous... I was tremendously drawn to him and he was eager to know his old friend's new young wife. Darrow had a great interest in women."

Clarence Darrow, the author of several books, including Crime, its Cause and Treatment (1925), The Prohibition Mania (1927) and an autobiography, The Story of My Life (1932), died on 13th March, 1938.

Primary Sources

(1) Clarence Darrow, The Story of My Life (1932)

From my youth I was always interested in political questions. My father, like many others in northern Ohio, had early come under the spell of Horace Greeley, and, as far back as I can remember, the New York Weekly Tribune was the political and social Bible of our home. I was fifteen years old when Horace Greeley ran for the presidency. My father was an enthusiastic supporter of Greeley and I joined with him; and well do I remember the gloom and despair that clouded our home when we received the news of his defeat.

Our candidate, Samuel J. Tilden, was elected in 1876, but was not allowed to take his seat. The Civil War was not then so far in the background as it is now, and any sort of political larceny was justifiable to save the country from the party that had tried to destroy the union. So, though Tilden was elected, Rutherford B. Hayes was inaugurated and served Tilden's term.

(2) Clarence Darrow, The Story of My Life (1932)

During these early years in Chicago I was very much interested in what passes under the name of "radicalism" and at one time was a pronounced disciple of Henry George. But as I read and pondered about the history of man, as I learned more about the motives that move individuals and communities, I became doubtful of his philosophy.

Socialism seemed to me much more logical and profound; Socialism at least recognised that if man was to make a better world it must be through the mutual effort of human units; that it must be by some sort of co-operation that would include all the units of the state. Still, while I was in sympathy with its purposes, I could never find myself agreeing with its methods. I had too little faith in men to want to place myself entirely in the hands of the mass. And I never could convince myself that any theory of Socialism so far elaborated was consistent with individual liberty.

(3) Clarence Darrow, comments on Trade Unions during the trial of Charles Moyer, William Hayward and George Pettibone in 1907.

Let me tell you, gentlemen, if you destroy the labor unions in this country, you destroy liberty when you strike the blow, and you would leave the poor bound and shackled and helpless to do the bidding of the rich. It would take this country back to the time when there were masters and slaves.

I don't mean to tell this jury that labor organizations do no wrong. I know them too well for that. They do wrong often, and sometimes brutally; they are sometimes cruel; they are often unjust; they are frequently corrupt. But I am here to say that in a great cause these labor organizations, despised and weak and outlawed as they generally are, have stood for the poor, they have stood for the weak, they have stood for every human law that was ever placed upon the statute books. They stood for human life, they stood for the father who was bound down by his task, they stood for the wife, threatened to be taken from the home to work by his side, and they have stood for the little child who was also taken to work in their places - that the rich could grow richer still, and they have fought for the right of the little one, to give him a little of life, a little comfort while he is young. I don't care how many wrongs they committed, I don't care how many crimes these weak, rough, rugged, unlettered men who often know no other power but the brute force of their strong right arm, who find themselves bound and confined and impaired whichever way they turn, who look up and worship the god of might as the only god that they know - I don't care how often they fail, how many brutalities they are guilty of. I know their cause is just.

I hope that the trouble and the strife and the contention has been endured. Through brutality and bloodshed and crime has come the progress of the human race. I know they may be wrong in this battle or that, but in the great, long struggle they are right and they are eternally right, and that they are working for the poor and the weak. They are working to give more liberty to the man, and I want to say to you, gentlemen of the jury, you Idaho farmers removed from the trade unions, removed from the men who work in industrial affairs, I want to say that if it had not been for the trade unions of the world, for the trade unions of England, for the trade unions of Europe, the trade unions of America, you today would be serfs of Europe, instead of free men sitting upon a jury to try one of your peers. The cause of these men is right.

(4) Clarence Darrow, comments on the possible conviction and execution of William Hayward for the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg (1907)

He (William Hayward) has fought many a fight, many a fight with the persecutors who are hounding him into this court. He has met them in many a battle in the open field, and he is not a coward. If he is to die, he will die as he has lived, with his face to the foe.

To kill him, gentlemen? I want to speak to you plainly. Mr. Haywood is not my greatest concern. Other men have died before him, other men have been martyrs to a holy cause since the world began. Wherever men have looked upward and onward, forgotten their selfishness, struggled for humanity, worked for the poor and the weak, they have been sacrificed. They have been sacrificed in the prison, on the scaffold, in the flame. They have met their death, and he can meet his if you twelve men say he must.

Gentlemen, you short-sighted men of the prosecution, you men of the Mine Owners' Association, you people who would cure hatred with hate, you who think you can crush out the feelings and the hopes and the aspirations of men by tying a noose around his neck, you who are seeking to kill him not because it is Haywood but because he represents a class, don't be so blind, don't be so foolish as to believe you can strangle the Western Federation of Miners when you tie a rope around his neck. Don't be so blind in your madness as to believe that if you make three fresh new graves you will kill the labor movement of the world. I want to say to you, gentlemen, Bill Haywood can't die unless you kill him. You have got to tie the rope. You twelve men of Idaho, the burden will be on you. If at the behest of this mob you should kill Bill Haywood, he is mortal. He will die. But I want to say that a hundred will grab up the banner of labor at the open grave where Haywood lays it down, and in spite of prisons, or scaffolds, or fire, in spite of prosecution or jury, these men of willing hands will carry it on to victory in the end.

(5) H. L. Mencken, Baltimore Evening Sun (21st July, 1925)

At last it has happened. After days of ineffectual argument and legal quibbling, with speeches that merely skirted the edges of the matter which everyone wanted discussed in the Scopes anti-evolution trial. William Jennings Bryan, fundamentalist, and Clarence Darrow, agnostic and pleader of unpopular causes, locked horns today under the most remarkable circumstances ever known by American court procedure.

It was on the courthouse lawn, where Judge Raulston had moved so that more persons could hear, with the Tennessee crowds whopping for their angry champion, who shook his fist in the quizzical satiric face of Mr. Darrow, that Mr. Bryan was put on the stand by the defense to prove that the Bible need not be taken literally.

The youthful Attorney General Stewart, desperately trying to bring the performance within legal bounds, asked, "What is the meaning of this harangue?" "To show up fundamentalism," shouted Mr. Darrow, lifting his voice in one of the few moments of anger he showed, "to prevent bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the educational system of the United States."

Mr. Bryan sprang to his feet, his face purple, and shook his fist in the lowering, gnarled face of Mr. Darrow, while he cried: "To protect the word of God from the greatest atheist and agnostic in the United States."

And then for nearly two hours, while those below broke into laughter or applause or cried out encouragement to Mr. Bryan, Mr. Darrow goaded his opponent. His face flushed under Mr. Darrow's searching words, and he writhed in an effort to keep himself from making heated replies. His eyes glared at his lounging opponent, who stood opposite him, glowering under his bulging brow, speculatively tapping his arm with his spectacles.

No greater contrast in men could be imagined. The traps of logic fell from Mr. Darrow's lips as innocently as the words of a child, and so long as Mr. Bryan could parry them he smiled back, but when one stumped him he took refuge in his faith and either refused to answer directly or said in effect: "The Bible states it; it must be so."

(6) In 1911 Clarence Darrow defended James and Joseph McNamara who had been charged with the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building.

The one reason that made me most anxious to save their lives was my belief that there was never any intention to kill any one. The Times building was not blown up; it was burned down by a fire started by an explosion of dynamite, which was put in the alley that led to the building. In the statement that was made by J. B. McNamara, at the demand of the State's attorney before the plea was entered, he said that he had placed a package containing dynamite in the alley, arranged the contraption for explosion, and went away. This was done to scare the employees of The Times and others working in non-union shops. Unfortunately, the dynamite was deposited near some barrels standing in the alley that happened to contain ink, which was immediately converted into vapor by the explosion, and was scattered through the building, carrying the fire in every direction.

(7) Clarence Darrow, The Story of My Life (1932)

It seemed that Loeb had gotten it into his head that he could commit a perfect crime, which should involve kidnapping, murder, and ransom. He had unfolded his scheme to Leopold because he needed some one to help him plan and carry it out. For this plot Leopold had no liking whatever, but he had an exalted opinion of Loeb. Leopold was rather undersized; he could not excel in sports and games. Loeb was strong and athletic.

Leopold had not the slightest instinct toward what we are pleased to call crime. He had, and has, the most brilliant intellect that I ever met in a boy. At eighteen he had acquired nine or ten languages; he was an advanced botanist; he was an authority on birds; he enjoyed good books.

From the beginning we never tried to do anything but save the lives of two defendants; we did not even claim or try to prove that they were insane. We did believe and sought to show that their minds were not normal and never had been normal.