Anna Strunsky

Anna Strunsky, the daughter of Elias Strunsky, a successful businessman, was born in Russia on 21st March, 1879. Her mother, Anna Horowitz Strunsky, had married her husband when she was only sixteen-years-old. Anna later recalled: "The only recollection of Russia for me was of a long village street and barefoot children and rambling hovels. I remembered myself a little child standing in a patch of sunlight and poking my fingers into a wall and finding it soft as sand." (1)

In 1885 the Strunsky family emigrated to the United States: "The Strunskys came to America carrying little beyond the family feather-beds and copperware. Like other hundreds of thousands, they made their first home on New York's Lower East Side, crowded into a tenement on Madison Street with the toilet in the backyard." (2)

The Strunsky's lived in New York City before moving to San Francisco in 1894. During her last year in high school, Anna joined the Socialist Labor Party (SLP). She later recalled: "You are born a socialist. You are born with music, or poetry or painting or science. You can't really become a socialist unless you're born that way." Her father, who had inspired her interest in politics, disagreed with her decision - "not because he grudged me to a great cause, but because he felt there was something amiss with the cause with which I had become infatuated." (3)

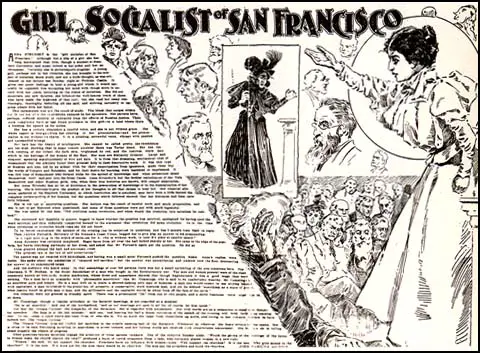

Anna Strunsky: Girl Socialist

Anna Strunsky was a talented orator and in October 1897, The San Francisco Examiner described her as the "Girl Socialist of San Francisco". John Hamilton Gilmour described her face as the "beauty of intelligence" rather than prettiness and noted her "pleading, sorrowful voice". Gilmour referred to her as Russian by birth but clearly identified her as Jewish with references to "Oriental" aspects of her appearance. (4)

As a young woman she met important political figures such as Emma Goldman and Daniel DeLeon. She later wrote: "The memory of the men and women that came and went throughout the years is perhaps the most romantic and the most precious memory of my life. This was my best school and from these personalities I got more than I have ever got out of books or halls of learning. Here were truly formative forces - meeting people in intellectual councils; budding genius, refugees, revolutionist; broken lives and strong lives, all made welcome, all met with reverence and with warmth." (5) A friend, Joseph Noel, described her as "a pretty little ingenue who played the part of a Stanford University intellectual to perfection. She had soft brown eyes, a kindly smile and a throaty little voice that did things to your spine." (6)

Stanford University

Strunsky became a student at Stanford University and in December 1899 met the young writer, Jack London. She later recalled: "Objectively, I confronted a young man of about twenty-two, and saw a pale face illumined by large, blue eyes fringed with dark lashes, and a beautiful mouth which, opening in its ready laugh, revealed an absence of front teeth, adding to the boyishness of his appearance. The brow, the nose, the contour of the cheeks, the massive throat, were Greek. His form gave an impression of grace and athletic strength, though he was a little under the American, or rather Californian, average in height. He was dressed in gray, and was wearing the soft white shirt and collar which he had already adopted."

London told her he was reading Seven Seas by Rudyard Kipling. "The Anglo-Saxons were the salt of the earth, he declared. He forgave Kipling his imperialism because he wrote of the poor, the ignorant, the submerged, of the soldier and sailor in their own language." Anna was a socialist and was critical of his desire to become rich. "I looked for the Social Democrat, the Revolutionist, the moral and romantic idealist; I sought the Poet. Exploring his personality was like exploring mountains and the valleys which stretched between troubled my heart ... He was a Socialist, but he wanted to beat the Capitalist at his own game. To succeed in doing this, he thought, was in itself a service to the Cause; to show them that Socialists were not derelicts and failures had certain propaganda value." (7)

London wrote warmly about Anna to Elwyn Irving Hoffman: "I should like to have you meet Miss Anna Strunsky some time. She is well worth meeting.... She has her exoteric circles and her esoteric circles - by this I mean the more intimate and the less intimate. One may pass from one to the other if deemed worthy.... She loves Browning. She is deep, subtle, and psychological. She is neither stiff nor formal. Very adaptive. Knows a great deal. Is a joy and delight to her friends. She is a Russian, and a Jewess, who has absorbed the Western culture, and who warms it with a certain oriental leaven." (8)

Anna Strunsky & Jack London

Jack was in love with Anna but did not feel she was the right woman to marry. It has been claimed by one biographer that London divided women into two groups. They were either "wonderful and unmoral and filled with life to the brim", or offering the promise of being "the perfect mother, made pre-eminently to know the clasp of the child". (9) Another biographer, Rose Wilder Lane, claimed he wanted a mother to "seven sturdy Anglo-Saxon sons". (10) Jack knew such a woman, Bessie Maddern, like Strunsky, a member of the Socialist Labor Party. The journalist, Joseph Noel, described Bess was "slender and, no doubt because she had her hair in the Pompadour mode, looked nearly as tall as Jack. Her face, strong, well-modelled, was enhanced by grey eyes fringed by chorus-girl lashes. When she smiled she was at her best. The surroundings were brightened." (11) Although he told Bessie he did not love her, he married her on 7th April 1900. After a brief honeymoon, husband and wife moved into a large house at 1130 East Fifteenth Street in Oakland.

Soon after his marriage, Anna Strunsky and Jack London been writing a joint novel, The Kempton-Wace Letters. The idea came when they were onboard London's boat, The Spray. Anna later wrote: "He (Jack London) was speaking of eugenics. He was saying that love was a madness, a fever that passes, a trick. One should marry for qualities and not for love. Before marrying one should make sure one is not in love. Love is the danger signal... Jack proposed that we write a book together on eugenics and romantic love. The moon rose, paled, and faded from the sky. Then the night came awake and our sails filled. Before we landed we had our plot, a novel in letter form in which Jack was to be an American, an economist, Herbert Wace, and I am an Englishman, a poet, Dane Kempton, who stood in relation to him of father to son." (12)

James Boylan, the author of Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998) has pointed out: "They decided the method of collaboration - a real exchange of letters between her home in San Francisco and his across the bay in Oakland. Neither of them stated outright the underlying proposition, nor was there a hint of what Bessie (Jack London's wife) thought of it: that Anna would be attacking the loveless basis of his marriage, and he defending it, a possibly cataclysmic scenario." (13)

London told his friend, Cloudesley Johns: "A young Russian Jewess of San Francisco and myself have often quarrelled over our conceptions of love. She happens to be a genius. She is also a materialist by philosophy, and an idealist by innate preference, and is constantly being forced to twist all the facts of the universe in order to reconcile herself with her self. So, finally, we decided that the only way to argue the question out would be by letter." (14) A mutual friend, Joseph Noel, described her as "a pretty little ingenue who played the part of a Stanford University intellectual to perfection. She had soft brown eyes, a kindly smile and a throaty little voice that did things to your spine." (15)

London suggested that Anna lived with him and his wife during the final revision of the book. This made Bessie London very jealous. She later claimed that Anna and her husband would rise "at the unusually early hour of half-past four in the morning and would retire to Jack's study where they remained until breakfast time... immediately after breakfast they would wander off into adjacent woods, to remain away all day." (16) Anna had a slightly different interpretation of events: "During the first few clays of my stay Mrs. London was very cordial and manifested great interest in our work, but, after a stay of five days, I became convinced that, for some reason, Mrs. London had begun to dislike me. She said nothing of any importance to make me feel out of place, but, judging from several little occurrences, I decided it was best for me to leave the London home. I carried out my resolve and left Piedinont, much against Mr. London's will." (17)

The Kempton-Wace Letters was published by Macmillan in May 1903. Despite the company spending $2,000 on advertising, the book only sold 975 copies. Jack London's friend, George Sterling, was highly critical of the book and described it as "a spiritual misprint, a typographical error half a volume long." (18) Joseph Noel, praised Strunsky's contribution: "Courage, devotion, the power to hope largely, to dream bravely, are in her pages. The simplicity of faith in life and life's processes gives dignity and beauty to nearly all she writes under the name of Dane Kempton." (19)

Visit to London

Anna became close to Emma Goldman during this period. Goldman later wrote: "Anna and I became great friends. She had been suspended from Leland Stanford University because she had received a male visitor in her room instead of in the parlour. I told Anna of my life in Vienna and of the men students with whom we used to drink tea, smoke, and discuss all through the night. Anna thought that the American woman would establish her right to liberty and privacy, once she secured the vote. I did not agree with her." (20)

After leaving university Anna Strunsky decided to spend her $500 advance for the The Kempton-Wace Letters on a trip to London. She wrote to her publisher, George Platt Brett: "The advance enables me to take a long looked-for trip to the Old World and I am very happy. While in London I shall call on Kropotkin and others. I may be able to incarnate an echo from the International Revolutionary movement into a book which will be the Uncle Tom's Cabin of the capitalist regime. Could I do this I would not so much care what became of my life, could I write the book that would serve the cause and the muse at the same time." (21)

While in England she did visit Peter Kropotkin. Anna noted "the warmth of his hand and the embrace of his look" but was disappointed that he did not appear to be interested in the growth of anarchism: "Why does he not ask me about the movement in America? Does he not know I know." (22)

In September, 1903, she received a letter from Jack London telling her that The Kempton-Wace Letters was being republished with their names together on the title page (the first edition had been published anonymously and therefore could not take advantage of London's popularity). However, the book was still not selling in large numbers: "It is a good book, a big book, and, as we anticipated, too good & too big to be popular." (23)

On her return to San Francisco Anna Strunsky discovered that London had left his wife. She wrote to London expressing sympathy: "Cameron King sent me a newspaper clipping some weeks ago. I am sorry for all the unhappiness, and I am strong in my faith. You never meant to do anything but the right and the good - poor, ever dear, dreamer! You will never do wrong. I cried over the news, half in gratitude for your strength and half in sorrow, perhaps all in sorrow, for all the sadness with which you are weighted." (24)

At the time she was unaware that rumours were circulating that she had been responsible for the break-up of the marriage. In fact, Anna had always refused to become sexually involved with London. He had written to her about his failure to seduce her in August 1902. (25) London also told his friend, Joseph Noel: "It would have to be marriage if anyone went after Anna... You know what a hell of a fuss these little intellectuals make about their virginity." (26)

Anna Strunsky was named in Bessie London's divorce petition. (27) This was leaked to the newspapers. On 30th June, 1904, the San Francisco Chronicle, interviewed Anna about the case. She complained that the scandal had reduced her mother "almost to the stage of nervous prostration." She denied the "silly little stories about lovemaking that went on before Mrs. London's eyes." Anna added that London had never behaved inappropriately: "His behavior was most circumspect toward me and always has been... He was blindly in love with his wife." (28)

Jack London had left Bessie for another woman, Charmian Kittredge, who was a friend of his wife. However, he wanted to keep this from Bessie and so he was encouraging her to believe that Anna was the woman he was involved with. London's lawyers eventually persuaded Bessie to drop her allegations in return for him agreeing to build a house for her and to make alimony and support payments. Her original claim of adultery was changed to desertion. (29)

Anna told her sister: "Jack has his divorce. There hasn't been much more unpleasantness for me though what there was was hard enough to bear. It was a plain case of blackmail. The divorce was obtained by his wife on the grounds of desertion. I am very glad he has his freedom at last. He has suffered bitterly. Further, I do not know. I hide nothing from you dearest. I think we do not love each other but I may be slandering a supreme feeling in thinking so. I am too breathless from the race for happiness and do not know. After all, I have not raced very hard. I have the Semitic temperament that gives up over readily and I have ever had a genius for giving up. I must be fought for gallantly to be won and I think lack would rather wait than fight. He, too, is tired. He is a pessimist and what has a pessimist to do with love? So, dearest, you know all." (30)

1905 Russian Revolution

After the 1905 Russian Revolution Anna Strunsky established a branch of the Friends of Russian Freedom in San Francisco. Other members included Jack London, William English Walling, George Sterling, Cameron King and Austin Lewis. Strunsky became chairman and produced a leaflet calling for "sympathy and help" for the Russian people. Walling, who was just about to leave for Europe sent her a note: "I almost shouted with delight at the dash with which you have under taken your Russian movement. Your leaflet is the best yet." (31)

Walling visited Paris in the summer of 1905. While in the city he met sixteen-year-old, Anna Berthe Grunspan, a recent arrival from Russia. He asked her if she was an "Hebrew". When she said she was, he replied that he was "very fond of Hebrew ladies". According to his biographer, James Boylan: "She recently had left school to become a shop girl. She lived with her family in quarters so humble that, she recalled later, she tried to keep Walling from paying a call. He began to see her several times a week, then every night. They entered a sexual liaison that, in his account, began within a few days... Her persuaded her to quit her job, assuring her that he would give her money equivalent to her pay." (32)

Walling took her on holiday to Germany. In order to get a room in a hotel in Berlin he was forced to claim that Anna was his wife. She later claimed that she assumed that they now were engaged to be married. (33) However, Walling claimed he told her the relationship was over and took her to the railway station and "with great difficulty" put her on the train back to Paris. He also supplied her with money so that she could go to London where she could receive training in English secretarial skills." (34)

In November 1905 William English Walling wrote to Anna Strunsky telling her that he intended going to St. Petersburg to witness the impact of the 1905 Russian Revolution, he sent her a telegram inviting her to join him. "I intend to preach (in American publications) the necessity in Russia of: (i) The stirring of the masses to revolt - of the lower orders, to the utmost (ii) Widespread battle against Cossacks and police and execution of bureaucrats (iii) The most complete political revolution, perhaps a republic." (35)

Anna and her sister Rose Strunsky, took up the offer and arrived in December, 1905: "He (Walling) met us at the train, dressed in a big Russian coat and an astrakhan cap. I kissed him." Strunsky was excited by the revolutionary atmosphere of the city. "On the streets, they were selling pamphlets, the covers of which were decorated with the portraits of Karl Marx, Bakunin, Kropotkin. In the windows of book shops were displayed photographs of Sophi Perovski, who was executed for taking part in the assassination of Alexander II; of Vera Zassulich, the first to commit a deed of violence for political reasons in modern Russia; of Vera Figner, whose resurrection from the Fortress of Schlusselburg had just taken place... More astounding... were the cartoons which appeared several times a day were bought as quickly as they could be had - cartoons portraying the Czar swimming in a sea of blood, mice gnawing away the foundation of the throne... Was I dreaming? Free press, free speech, free assemblage in Russia." (36)

Anna Strunsky was shocked by the level of violence that she saw. She was in a restaurant when they were singing "God save the Czar!". However, a young man sitting with his mother and girlfriend, refused to join in. An officer at a nearby table walked over to him and commanded him to rise. When he refused, he shot him dead. She wrote to her brother, Hyman Strunsky about how the incident drew her closer to Walling: "On New Year's Eve we saw a student shot to death in a cafe for refusing to sing the national hymn, and our love which had been filling our hearts from the hour of our meeting suddenly burst into speech. It was baptised in blood you see, as was fitting for a love born in Russia." Anna also wrote to her father admitting her love for Walling: "I found Russia in the same hour that I found love. It was fated. Russia had stood for quite other things, but the man I love and who loves me, so tenderly, dear, as tenderly as mother, and as deeply has opened vistas before me and changed the face of things forever." (37)

On 26th January, 1906, Walling wrote to his parents about the woman he intended to marry: "She is considered by Mr. Brett the manager of Macmillans as nothing less than a genius in her work as a writer. She is the most known speaker on the Coast. She is loved, sometimes too much, by everybody that knows her - literary men, Settlement people, Socialists. All my friends know her. She is 26 and very healthy and strong... Of course she is a Jewess and her name is Anna Strunsky (but I hope to improve that - at least in private life - but we haven't spoken much of such things). (38)

Strunsky wrote to her father: "We are in the city where you have spent so many happy and so many bitter years... I found Russia in the same hour that I found love. It was fated. Russia had stood for quite other things, but the man I love and who loves me, so tenderly, dear, as tenderly as mother, and as deeply has open vistas before me and changed the face of things forever." (39) She confided in her diary: "Henceforth I am no longer alone. I am more afraid of this than a sick child alone in the dark."

Anna Strunsky told Jack London the good news about her proposed marriage to William English Walling: You see, how my love throws me more upon the world than ever. We mean never to have a home, never to belong to a clique, never to prevent life from playing upon us, never to shield each other. This is not a theory, but a fact springing from the heart of the man who loves me. He is far less bourgeois than I and I am not bourgeois. He is my supreme comrade always, heart of my heart. Our lives will show you, friend of mine, how good this love is! (40)

On 31st March 1906, Anna Strunsky told her brother, Hyman Strunsky that they intended to marry but it would be an unconventional relationship: "We will never have a home - except each others arms - never let our love stand in the way of the world, in the way of any human association. We dedicate ourselves and each other to Life - that is our marriage sacrament." (41) She explained to her future mother-in-law: "I adapt myself so easily to conditions that it may be any country could be a home to me. I really feel something like world-citizenship, and provincialism of any kind is distasteful to me, but I am devoted to the future America and I consider that my life belongs to it. English and I see wholly as one in this feeling, as we are on everything that is fundamental and essential." (42)

Marriage to William English Walling

Anna Strunsky was unwilling to have a conventional marriage. She told Rosalind English Walling: "Neither English nor I belong to any creed, and a religious ceremony would be farcical to us, at best something less than sincere and beautiful. A greater reason still is that according to the law of Moses I cannot marry English at all, and there is no Rabbi in the world who could listen to our troth without committing sacrilege! From the standpoint of the faith in which I was born I must be stoned to death for what I was about to do. My parents are very liberal yet I have heard them say they would rather see me dead than marry a Gentile. I should not record this at all for their attitude towards English is perfect... The Jewish religion would unite us only if English became a Jew, and another form of religious marriage is equally impossible for me. It would mean conversion on my part to have even a Unitarian minister officiate, and it would literally kill my mother." (43)

Walling explained to his mother why they decided to marry: "We are together all day and half the night in the same Hotel. We ought to be married. If we went back to be married it would... immediately result in a host of complications, inconveniences, heartburnings, strains and smaller little nuisances that puts it almost quite out of the question... Both of us believe thoroughly in romantic love (one love) in marriage and in all reasonable restraint. We shall marry sensibly and not hastily and we shall not behave as if we were married before we are. Outwardly we have broken most conventions. We go down the streets hand in hand, we kiss one another in the sleigh, we live in one another's sitting rooms and sometimes go into one another's bedrooms." (44)

Walling and Strunsky left Russia in May 1906. They arrived in Paris on 2nd June 1906, and married at the end of the month. The San Francisco Call newspaper carried the headline: "Girl Socialist Wins Millionaire". (45) Another newspaper, The Chicago American stated: "Socialism Finds Bride for a Rich Yankee in Russia" and compared their marriage to those of Graham Stokes and Rose Pastor and Leroy Scott and Miriam Finn, two rich men who married left-wing Jewish immigrants. (46)

Anna Strunsky explained to her brother it was not going to be a conventional marriage and that she refused to change her surname: "We got legally married, because we did not believe it best to run in the face of the world on this matter. But now that we have got married we don't talk of it. We don't like to remember that the law gives us a right over each other. Our love is so strong that we are not in the least afraid of being bruised by the legal form or any other bondage the world may lay upon us, but yet it is better not to remember too much the vulgarity and the meaninglessness of the promises we made to each other before the Mayor. (They were in French, and said too quickly, for us to understand.) I had to sign a paper regarding some property of English's and I signed Anna Strunsky Walling, my legal name-but all my other letters and writings I sign Anna Strunsky." (47)

Return to Russia

In October 1907 Strunsky and Walling returned to Russia. Soon after arriving in St. Petersburg they were arrested along with her sister, Rose Strunsky, who had been living in the country since December 1905. "When I opened the door of our apartment, I found a Chief of Police, gendarme spies, the proprietor of the hotel, and servants. The contents of our trunks lay scattered on floor, chairs and bed. The desks were littered with books and manuscripts. They were reading my letters, scrutinizing my photographs... When I entered the room and saw the confusion of clothes and papers, my checks flamed with anger and horror." Strunsky claimed they asked her: "Where do you hide your revolvers and dynamite." She told the interpreter. "Tell him that we are writers, and when we use weapons we use pen and ink and not arms." (48)

Other journalist friends such as Harold Williams and Ariadna Tyrkova, were also detained. All five were accused of writing articles supporting the revolutionaries. The American newspapers soon took up their case. The Boston Herald headed its story "Czar's Police Jail Harvard Men." (49) The The Chicago American reported that Elihu Root, the United States Secretary of State, had already protested about the behaviour of the authorities. (50) They were soon released but were deported.

Birth and Death

Anna Strunsky was heavily pregnant and decided to have her baby in Paris. It was born on 8th February, 1908, but died five days later: "When our first-born died and lay a little corpse on my breast, English not knowing she was still there and that nurse had not taken her away, flung himself full length on me, his arms around me, his tears falling full on my face and sobbed: Let us not wash away our grief in tears! This is a grief for all our life: Let us not feel it all at once!" (51)

At first Anna blamed her nurse, Miss Plumb, for her baby's death: "We trusted our darling into the hands of a friend. It seems as if the hand of God held us from snatching the child away from her, for none of us liked her, all of us now remember that she filled us with dread, that she was coarse and queer and eminently out of place amongst us, trusting and fond hearts that we are, and yet none of us drove her from the house." (52) This appears to have been a temporary feeling and she wrote in less vengeful tones to her mother-in-law: "It is twelve days since my baby died-the exquisite, beautiful, perfect little child that we were allowed to keep for only five days!... I called her 'my little International' - the beauty and loveliness of every country in Europe entered in the making of her." (53)

Books on Russia

On their return to the United States both Anna Strunsky and William English Walling worked on books about the 1905 Russian Revolution. Anna's book remained unfinished but Walling's book, Russia's Message: The True World Import of the Revolution, was published in June 1908. He admitted that he had "not dwelt on personal experience" and owed "little to writers of books and much to active leaders of the movement". The book was mainly made up of hundreds of interviews with officials and revolutionaries, peasants and workers, priests and politicians. This included Leon Trotsky and Lenin who he described as "perhaps the most popular leader in Russia". (54)

The book managed to obtain some good reviews. Walling reported that 27 out of the 30 newspaper reviews were favourable. The Nation praised him for his treatment of the peasants and said that his book was the only one to rank with the work of the British scholar Bernard Pares. However, he did come under attack from his uncle, William English, because of his negative comments about his friend, Albert J. Beveridge, the Republican senator from Indiana and his book, The Russian Advance (1903). English also disliked what he considered was "socialistic" propaganda. "The book will do one good thing certainly in any event and that is you can never go back to Russia... For which all of us are thankful." (55)

Anna Strunsky & the NAACP

On 14th August, 1908, Walling and Strunsky heard about the Springfield Riot in Illinois, where a white mob attacked local African Americans. During the riot two were lynched, six killed, and over 2,000 African Americans were forced to leave the city. Walling and Strunsky decided to visit Springfield "to write a broad, sympathetic and non-partizan account". When they arrived they interviewed Kate Howard, one of the leaders of the riots. Walling later wrote: "We at once discovered, to our amazement, that Springfield had no shame." He and Anna were treated to "all the opinions that pervade the South - that the negro does not need much education, that his present education even has been a mistake, that whites cannot live in the same community with negroes except where the latter have been taught their inferiority, that lynching is the only way to teach them, etc."

On 3rd September 1908, William English Walling published his article, Race War in the North. Walling complained that "a large part of the white population" in the area were waging "permanent warfare with the Negro race". He quoted a local newspaper as saying: "It was not the fact of the whites' hatred toward the negroes, but of the negroes' own misconduct, general inferiority or unfitness for free institutions that were at fault." Walling argued that they only way to reduce this conflict was "to treat the Negro on a plane of absolute political and social equality".

Walling argued that the people behind the riots were seeking economic benefits: "If the white laborers get the Negro laborers' jobs; if masters of Negro servants are able to keep them under the discipline of terror as I saw them doing in Springfield; if white shopkeepers and saloon keepers get their colored rivals' trade; if the farmers of neighboring towns establish permanently their right to drive poor people out of their community, instead of offering them reasonable alms; if white miners can force their negro fellow-workers out and get their positions by closing the mines, then every community indulging in an outburst of race hatred will be assured of a great and certain financial reward, and all the lies, ignorance and brutality on which race hatred is based will spread over the land."

Walling suggested that racists were in danger of destroying democracy in the United States: "The day these methods become general in the North every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as in the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war, which shall obliterate not only the remains of slavery but all other obstacles to a free democratic evolution that have grown up in its wake. Yet who realizes the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid. (56)

Mary Ovington, a journalist working for the New York Evening Post, responded to the article by writing to Walling and inviting him and a few friends to her apartment on West Thirty-Eighth Street. Ovington was impressed with Walling: "It always seemed to me that William English Walling looked like a Kentuckian, tall, slender; and though he might be talking the most radical socialism, he talked it with the air of an aristocrat." (57)

Also at the meeting was Charles Edward Russell. He argued: "Wittingly or unwittingly, the entire South was virtually a unit in support of hatred and the ethics of the jungle. The Civil War raged there still, with hardly abated passions. The North was utterly indifferent where it was not covertly or sneakingly applause of helotry... The whole of the society from which Walling emerged was crystallized against the black man; to view the darker tinted American as a human being was not good form; to insist upon his rights was insufferable gaucherie." (58)

They decided to form the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). The first meeting of the NAACP was held on 12th February, 1909. Early members included Anna Strunsky, William English Walling, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Lillian Wald, Florence Kelley, Mary Church Terrell, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, George Henry White, William Du Bois, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, William Dean Howells, Fanny Garrison Villard, Oswald Garrison Villard and Ida Wells-Barnett.

Anna Strunsky became pregnant again but miscarried at three and a half months, on the first anniversary of Rosalind's birth. "I do not feel that I can survive this horror that has come to me. And if ever I prayed at all I would pray that the peace which passes understanding, the peace which comes only with death wrap me round for ever." (59) However, over the next few years she did give birth to four children, Rosamond, Anna, Georgia, and William Hayden English.

Anna Berthe Grunspan

Anna Berthe Grunspan moved to New York City and on 21st February, 1911, the New York Times reported: "Anna Bertha Grunspan, a Russian girl, who spent most of her life in Paris, told a Supreme Court jury before Justice Giegerich yesterday the story on which she hopes to recover $100,000 for breach of promise from William English Walling, the wealthy Socialist and husband of Anna Strunsky Walling, a settlement worker and writer on Russian politics. Walling denies that he ever promised to marry Miss Grunspan, who now lives at 245 East Thirtieth Street." (60)

Miss Grunspan told the court: "He told me that I was the sweetest and dearest woman on earth and that he ought to know, because he had been all over the world. He said I would make him the happiest man in the world if I would marry him. He said he was rich and that it was criminal for me to work when he had so much money." On 29th July, 1905, in the company of her parents "put a new ring, with a design of three leaves and studded with two pearls and a diamond, on her finger".

The New York World reported that: "Mrs. Walling - Anna Strunsky, authoress and revolutionist - was present in court... Several hundred comrades, men and women, packed the big courtroom. At the recesses they formed excited groups and discussed the trial in many languages." Strunsky also gave evidence in the case. Her mother-in-law, Rosalind English Walling, later recalled: "I think Anna's corroboration of her husband's testimony was good, and she said just what she ought to have said." (61)

During the trial Anna Berthe Grunspan attacked the behavior of Walling in the court: "Oh, that man, that man, I can't stand the way he's looking at me. His look goes right through me, and it's the nastiest kind of a look. It gives me the horrors. And then, too, the way he and that woman, his wife, chuckle and laugh together." Grunspan also complained about Strunsky smiling and laughing in court. (62)

The all male jury found Walling not guilty. However, the trial did have an impact on his image. Fred R. Moore, the editor of the New York Age, wrote: "We hope that no colored man or woman will in the future disgrace our race by inviting Mr. Walling in their home or ask him to speak at any public meeting." (63) There were also complaints by the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and although he remained on the board he rarely attended meetings.

Childbirth

The death of her first child in February 1908 hit Anna Strunsky badly. This was followed by a couple of miscarriages. Inez Gilmore met he during this period: "Anna is very beautiful I think, a creature of mahogany and jet - of red showing through the satin brown; brown eyes, shining, clear and pure as pools with drowned stars in them-a most lucent gleamy agate. Her hands are lovely. Her voice is deep, rich with organ-notes in it. Her accent is charming. Her diction, as Frank Burgess always told me, exquisitely clear and elegant. I love her moist, rippling black hair. Her figure has thickened. She will be a haus-frau type in a few years. But always that soul will shine through that naive eloquence; always that temperamental fervor will prove an illuminating fire." (64)

Anna Strunsky gave birth to Rosamond on 29th January 1910. Anna was overjoyed at having a healthy child. This was quickly followed by two more children, Anna and Georgia. Walling wrote to his mother that "Georgia... is by far the strongest and healthiest we have had. Anna looks as well as when you saw her. Five hours labor, half hour of severe pains." (65)

Having three children under the age of four meant that she had little time for writing. She had been writing her book on the 1905 Russian Revolution for the last five years. Emma Goldman told her she was surprised that she had sacrificed her career by having so many children. "What a strange girl you are to have so many kiddies, especially when you go through such a terrible ordeal during pregnancy." (66)

The Masses

In 1912, their Max Eastman , became editor of the left-wing magazine, The Masses. Organised like a co-operative, artists and writers who contributed to the journal shared in its management. Walling and Strunsky joined the team as did Floyd Dell, John Reed, Crystal Eastman, Sherwood Anderson, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Amy Lowell, Louise Bryant, John Sloan, Dorothy Day, Cornelia Barns, Alice Beach Winter, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

In his first editorial, Eastman argued: "This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers." (67)

Walling was given the job of writing a column about worldwide socialism. Anna Strunsky tried to persuade Jack London to supply articles: "Max Eastman mailed you yesterday the three copies of The Masses that have so far appeared. We are all quite mad about this publication, and we want something from you, if it is only a paragraph. Eugene Debs wrote a letter - do the same, if you are not inclined to write anything more at the present moment, but a word from you at this critical juncture in the infant life of the magazine we must have." (68) However, London had lost interest in socialism and he did not reply to the letter.

First World War

William English Walling, like most of his friends, was totally against war. He wrote that he supported "not only the ordinary Socialist opposition to all wars, but the taking of the most desperate means to prevent them". (69) However, on the outbreak of the First World War he changed his mind on the subject as he agreed with H. G. Wells that the conflict would lead to a revolution against Kaiser Wilhelm II and Tsar Nicholas II. (70)

Walling wrote to Jack London in 1915: "I am an ultra-optimist about the war. I think it is altogether going to eclipse the French Revolution and have an infinitely greater result for good in all directions - before we are through with it... the everlasting smash of German civilization and all it stands for is worth almost any price." Walling added that "practically all of the men in the Socialist movement in the different countries are, to his mind, pro-Germans and pacifists, peace-at-any-price men." (71)

Anna Strunsky disagreed with her husband over this issue of the First World War. Whereas he urged President Woodrow Wilson to join on the side of the allies, Strunsky joined the Women's Peace Party and argued for a negotiated peace. Other women involved in the organization included Jane Addams, Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Mary Heaton Vorse, Freda Kirchwey, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt and Sophonisba Breckinridge. Walling described the activities of these women as "bourgeois pacifism". (72)

Despite all her other activities Anna Strunsky continued to write and published her novel, Violette of Père Lachaise in 1915. It was dedicated to Rosalind English Walling, her dead child, and on the dust jacket it said: "A subjective biography, the author calls it, But, though it is the spiritual development of a specially gifted individual, it is also the development of every individual, the adjustment of everyone to life and death... In this way, Mrs. Walling, herself a prominent figure in the social revolution, embodies her conception of the modern philosophy of love and revolution idealism and democracy. Violette is a forerunner of the future." (73)

Walling's support for the war brought him into conflict with Max Eastman, the editor of The Masses, who argued that the war had been caused by the imperialist competitive system. Eastman and journalists such as John Reed who reported the conflict for the journal argued that the USA should remain neutral. Most of those involved with the journal agreed with this view but there was a small minority, including Walling, Graham Stokes, John Spargo and Upton Sinclair, who wanted the United States to join the Allies against the Central Powers. When Walling failed to convince his fellow members he ceased to contribute to the journal.

William English Walling now began to attack those in the the American Socialist Party who opposed the war as really being secret supporters of Germany. Emma Goldman wrote to Anna Strunsky: "I hope you and the children are well and that English is not quite as rabid on the war question as in the past. It is absolutely inexplicable to me how revolutionists will become so blinded by the very thing they have been fighting for years." (74)

Walling was even more critical of his former comrades in private. In a letter to his father he wrote: "A Washington friend on the inside told me today he expected that Germany would declare war on us after we had taken certain hostile commercial action. I expect this too - within a few weeks. I desire it - because of pro-Germans, wild Irish, Catholics, anti-Japanese, peace fanatics, treasonable Socialists and the armament trust in this country. Only that will silence them all." (75)

Anna's first love, Jack London, died at his California ranch on 22nd November, 1916. Anna was heavily pregnant at the time and was unable to go to the funeral. The following month, on 22nd December, William Hayden English Walling was born. It was their only son. Her mother-in-law wrote: "I wish I had been with you. I know what that terror is and English was away when you wrote too - I do hope he came soon after - Well, it is all happily over and a son is born unto you." (76)

Russian Revolution

After the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917 Anna Strunsky supported armed struggle to protect the gains of the revolution. Walling wrote to Strunsky in March, 1917: "Of course I think your proposal to attack in the back those who are giving up their lives for democracy, peace, and anti-militarism is criminal to the last degree. But the world is moving in spite of all you do to help the militarists and reactionaries. You are their accomplice and neither I nor mankind, nor the genuine idealists and revolutionaries of the world will ever forget or forgive what your kind has said and done in this great hour. If I fight it will be against the traitors to internationalism - I trust you will not be among them." (77)

Strunsky replied that women tended to value peace more than men: "Ever since Rosalind English was born I have seen everybody as a little baby shining on a pillow or on a mother's breast; I have had a mother's tenderness towards the world of men and women; I could always see everybody as they were born to be, not as they were." However, she had changed her mind about the use of violence because of events in Russia: "A Revolutionist believes in the people and opposes the established order - my faith in the people and opposition to establishment law and order are deep and integral with my whole being. I am not a Junker because I not only give my consent to the rioters of the streets of Petrograd for what they did, but had I not you and our children I would not have hesitated, even at this distance to join them and fall by their side for a regenerated Russia. As it is, rich and wonderful as my life is with you and my children I do not at all feel that I belong wholly to myself and the time may come when I, the most passionate lover of life ever born, may go out to meet death for my Cause - as gallantly as any soldier ever did - but I will make sure that it is my Cause and not the Cause of my enemy... I have capitulated to your point of view about this War. What else can we do with the enemy at the door of the Russian Revolution but give him battle and rout him? Until the German people revolt we have to repel their advance upon freedom and democracy with the edge of the sword." (78)

William English Walling feared that the Provisional Government in Russia would negotiate a peace settlement with Germany. Walling joined forces with Graham Stokes, Upton Sinclair and Charles Edward Russell, to send a telegram to Alexander Kerensky, the Minister of War, warning against a separate peace. (79) William B. Wilson, Secretary of Labor, suggested to President Woodrow Wilson that Walling should be sent to Petrograd to negotiate with Kerensky. "I know of no Socialist in this country who has been more in touch with the Socialistic group of Russia or understands them better than Mr. Walling." (80)

Emma Goldman was furious with Walling and other pro-war socialists and wrote in Mother Earth: "The black scourge of war in its devastating effect upon the human mind has never been better illustrated than in the ravings of the American Socialists, Messrs. Russell, Stokes, Sinclair, Walling, et al.... As to English Walling, he was the reddest of the red. Though muddled mentally he was always at white heat emotionally as syndicalist, revolutionist, dissenter, etc... One might overlook the renegacy of a Charles Edward Russell. Nothing else need ever be expected from a journalist. But for men like Stokes and Walling to thus become the lackeys of Wall Street and Washington, is really too cheap and disgusting." (81)

William English Walling had now abandoned his beliefs in socialism. In an article published on 10th November 1917, he made a savage attack on Socialist Party of America. Entitled "Socialists: The Kaiser-Party" it argued that the party was under the control of "several million German-drilled voters". Walling called for the suppression of dissent: "We must isolate it, brand it and set the rest of the nation against it... we can be certain of nothing unless we take the offensive against these Allies of the Kaiser - and take it now." (82)

Walling had moved so far to the right he accused the Woodrow Wilson administration of being infected with bolshevism: "The evidence from public expressions of influential friends of Mr. Wilson is sufficient enough to make a book to prove the pro-Bolshevist tendencies of our government... I really believe that every revolutionary movement in Europe from the mild and revolutionary Socialism of Arthur Henderson to Bolshevism has been largely sustained by the Wilson appointees with the full knowledge of Mr. Wilson himself." (83)

Divorce

The relationship between William English Walling and Anna Strunsky became very difficult after their political differences during the First World War. Walling left the family home and in 1932 filed for a Mexican divorce, but Anna refused to recognize the end of the marriage. Anna wrote to her son-in-law Rifat Tirana in November 1932: "English promised me he would come back when he left me. Eventually he will keep that promise... He has made mistakes and so have I, and for the most part each was the cause of the other's mistakes... Now we have come to an impasse, because I look upon my life with English as a collaboration. He cannot ask me to write the wrong ending to the book we have been writing all these years. All he can do is suspend publication - which is exactly what has happened." (84)

On 27th September, 1933, Strunsky wrote in her diary: "I was wrong when I fell in love with him and began my life with him. I was never safe in his hands. He worked against me in the dark with my children, his mother, so passionately dear to me, my friends and family. He did worse - he worked against me in the dark with himself, in his own heart, for he never gave me a chance to explain, to defend myself." (85)

Strunsky's old friend, Leonard D. Abbott, asked her to marry him. James Boylan, the author of Revolutionary Lives (1998), has pointed out: "She loved him (Abbott), she told herself, but she did not admit him to the status of lover. She remained always radical in public, Victorian and bourgeoisie in private." (86)

William English Walling died of pneumonia in Amsterdam on 12th September, 1936. On his bedside table was a new edition of Michel de Montaigne, with a passage marked: "Do not be afraid to die away from home, do not abandon travel when ill or old."

Anna Walling continued to be active in politics and was a member of the War Resisters League, the American League to Abolish Capital Punishment, the League for Industrial Democracy, and the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People.

Strunsky never completed her book on the 1905 Russian Revolution. As her biographer, James Boylan, has pointed out: "It was true that she had fallen far short of her aspirations. Although she never renounced her faith in a vaguely cooperative, utopian socialism, doctrine hardly played a greater role in her later life than, say, theology among suburban Christians. Once she had made her true lifetime commitment, to marriage, she retained her freedom of opinion but gave up freedom in her economic environment. She lacked the will and the urgent circumstances of the women she portrayed in her account of the revolution to make her own life truly revolutionary." (87)

Anna Strunsky Walling died on 25th February 1964. Her daughter Anna English Walling, found her in her apartment, lying among papers she was still struggling to put in order. (88)

Primary Sources

(1) Anna Strunsky, Revolutionary Lives, unpublished memoir (1942)

We had climbed the dusty stairs and had sat in the garish hall lighted by flickering gas-jets. We had looked about ... at the red-draped speaker's stand, the pictures on the walls of Marx, Engels, Liebknecht, Lassalle, at the black letters on white stretched across the platform: "Workers Unite! You have only your chains to lose, you have a world to gain!"

We had listened to the eloquence of the speaker, Austin Lewis, a London University man who brought something of an old-world culture to our Western movement. It was as if we were there in that Paris which we had never seen, in a time before we were born. We were by the side of the Communards on those barricades. In that hour we re-lived those days and nights of conflict and tragedy.... The speaking over, we rose and sang the Marseillaise and the International.

He was there that night.... He rose from a seat well towards the front and walked towards the platform. I too was on the way to the speaker."Do you want to meet him he is Jack London, a Comrade who has been speaking in the street in Oakland. He has been to the Klondyke and he writes short stories for a living."

He (Jack London) was proud, he said, that we had men like Austin Lewis with us. Already some of the best and finest had crossed the barriers of class to side with the people. Then he hurried away to catch the last ferry for Oakland where he lived with his mother.... Jack London seemed at once younger and older than his years. There was that about him that made one feel that one would always remember him. He seemed the incarnation of the Platonic ideal of man, the body of the athlete and the mind of the thinker....

The light played on his face. He had large blue eyes, dark lashes, a broad forehead over which a lock of brown hair fell and which he often brushed aside with his small, finely shaped hand. He was deep-chested, wide shouldered... Jack picked up a copy of Rudyard Kipling's Seven Seas, recently published, turned to the Song of the English and read it aloud. The Anglo-Saxons were the salt of the earth, he declared. He forgave Kipling his imperialism because he wrote of the poor, the ignorant, the submerged, of the soldier and sailor in their own language...

There was a fire in the grate and its light played on his face. He spoke of his marriage. He had acted with directness and conviction perhaps only because he had needed to be convinced. He had acted through what might be called defense psychology. He had arrived at sonic idea that it would be easy to trick his imagination, to harness his fancies. One had a purpose in marrying. One married for qualities. He would found his marriage on that friendship in which love resolves itself. It was as if he was saying he could be happy without happiness - this romantic youth.... He explained how he had worked it out-there was to be freedom within the frame of marriage... He thought it something new, modern, not realizing that he was being old-fashioned and living like the majority who do not aspire to the luxury of love.

(2) Jack London, letter to Anna Strunsky (21st December 1899)

Somehow I am like a fish out of water. I take to conventionality uneasily, rebelliously. I am used to saying what I think, neither more nor less. Soft equivocation is no part of me. As had I spoken to a man who came out of nowhere, shared my bed and board for a night, and passed on, so did I speak to you. Life is very short. The melancholy of materialism can never be better expressed than by Fitzgerald's "O make haste." One should have no time to dally. And further, should you know me, understand this: I, too, was a dreamer, on a farm, nay, a California ranch. But early, at only nine, the hard hand of the world was laid upon me. It was never relaxed. It has left me sentiment, but destroyed sentimentalism. It has made me practical, so that I am known as harsh, stern, uncompromising. It has taught me that reason is mightier than imagination; that the scientific man is superior to the emotional man. It has also given me a truer and a deeper romance of things, an idealism which is an inner sanctuary and which must be resolutely throttled in dealing with my kind, but which yet remains within the Holy of Holies, like an oracle, to be cherished always but to be made manifest or be consulted not on every occasion I go to market. To do this latter would bring upon me the ridicule of my fellows and make me a failure; to sum up, simply the eternal fitness of things:

All of which goes to show that people are prone to misunderstand me. May I have the privilege of not so classing you?

Nay, I did not walk down the street after Hamilton - I ran. And I had a heavy overcoat, and I was very warm and breathless. The emotional man in me had his will, and I was ridiculous.

I shall be over Saturday night. If you draw back upon yourself, what have I left ? Take me this way : a stray guest, a bird of passage, splashing with salt-rimed wings through a brief moment of your life - a rude and blundering bird, used to large airs and great spaces, unaccustomed to the amenities of confined existence. An unwelcome visitor, to be tolerated only because of the sacred law of food and blanket.

(3) Jack London, letter to Anna Strunsky (15th March, 1900)

Regarding box... please remember that I have disclosed myself in my nakedness - all those vain efforts and passionate strivings are so many weaknesses of mine which I put into your possession. Why, the grammar is often frightful, and always bad, while artistically, the whole boxful is atrocious. Now don't say I am piling it on. If I did not realize and condemn those faults I would be unable to try to do better. But - why, I think in sending that box to you I did the bravest thing I ever did in my life.

Say, do you know I am getting nervous and soft as a woman. I've got to get out again and stretch my wings or I shall become a worthless wreck. I am getting timid, do you hear? Timid! It must stop. Enclosed letter I received to-day, and it brought a contrast to me of my then 'unfailing nerve' and my present nervousness and timidity. Return it, as I suppose I shall have to answer it some day.

(4) Anna Strunsky, letter to Katia Strunsky (2nd September, 1904)

Jack has his divorce. There hasn't been much more unpleasantness for me though what there was was hard enough to bear. It was a plain case of blackmail. The divorce was obtained by his wife on the grounds of desertion. I am very glad he has his freedom at last. He has suffered bitterly. Further, I do not know.

I hide nothing from you dearest. I think we do not love each other but I may be slandering a supreme feeling in thinking so. I am too breathless from the race for happiness and do not know. After all, I have not raced very hard.

I have the Semitic temperament that gives up over readily and I have ever had a genius for giving up. I must be fought for gallantly to be won and I think lack would rather wait than fight. He, too, is tired. He is a pessimist and what has a pessimist to do with love? So, dearest, you know all.

(5) Alex Kershaw, Jack London: A Life (1997)

Anna Strunsky, a young Russian Jewess with long, lustrous black hair.... Anna was from a Russian Jewish family that had escaped the pogroms roms in Russia and took pride in its connections with the notorious anarchist Emma Goldman and other radicals. Though she was just seventeen when she met Jack in autumn 1899 at a left-wing lecture, she was already called "the girl socialist of San Francisco". At Stanford University she had been suspended for "receiving a male visitor in her room instead of the parlour".

In Anna's eyes, Jack was "a young man with large blue eyes fringed with dark lashes, and a beautiful mouth which, opening in its ready laugh, revealed an absence of front teeth. The brow, the nose, the contour of the cheeks, the massive throat were Greek. His body gave the impression of grace and athletic strength. He was dressed in grey and was wearing a soft white shirt with collar attached, and black neck tie."

Jack was immediately infatuated with the romantic and spiritual Anna, even though he had developed an image of himself as a hard man who lived by the rule of cold logic. "He systematised his life," Anna later wrote. "Such colossal energy, and yet he could not trust himself! He lived by rule. Law, Order, and Restraint was the creed of this vital, passionate youth."

"I too was a dreamer," Jack confided to Anna shortly after his marriage to Bess: "But early, at only nine, the hard hand of the world was laid upon me. It was never relaxed. It has left me sentiment, but destroyed sentimentalism. It has made me practical, so that I am known as harsh, stern, uncompromising. It has taught me that reason is mightier than imagination; that the scientific man is superior to the emotional man." (letter from Jack to Anna 21st December, 1899)

As with many of his friends, the more Anna got to know Jack, the more concerned she became about his philosophy of life. Theirs would be a relationship of opposing minds. Time and again, as their friendship blossomed, Anna would combat his Spencerian belief that "all is law".

Our friendship can be described as a struggle - constantly I strained to reach that in him which I felt he was "born to be",' Anna later recalled. "I looked for the Social Democrat, the Revolutionist, the moral and romantic idealist; I sought the Poet. Exploring his personality was like exploring mountains and the valleys which stretched between troubled my heart ... He was a Socialist, but he wanted to beat the Capitalist at his own game. To succeed in doing this, he thought, was in itself a service to the Cause; to show them that Socialists were not derelicts and failures had certain propaganda value."

Anna warned Jack that to "pile up wealth, or personal success" was to play by the capitalists' rules. Such a game could only end one way - in the defeat of non-material ideals. She never doubted "the beauty and the warmth and the purity of his own nature". But she was afraid where his philosophy might lead him. "These ideas were not worthy of him," she thought. "They belittled him and eventually they might eat away his strength and grandeur."

(6) William English Walling, Race War in the North (3rd September 1908)

If the new Political League succeeds in permanently driving every negro from office; if the white laborers get the Negro laborers' jobs; if masters of negro servants are able to keep them under the discipline of terror as I saw them doing in Springfield; if white shopkeepers and saloon keepers get their colored rivals' trade; if the farmers of neighboring towns establish permanently their right to drive poor people out of their community, instead of offering them reasonable alms; if white miners can force their negro fellow-workers out and get their positions by closing the mines, then every community indulging in an outburst of race hatred will be assured of a great and certain financial reward, and all the lies, ignorance and brutality on which race hatred is based will spread over the land....

Either the spirit of the abolitionists, of Lincoln and of Lovejoy must be revived and we must come to treat the negro on a plane of absolute political and social equality, or Vardaman and Tillman (two of the South's leading spokesmen on race) will soon have transferred the race war to the North....

The day these methods become general in the North every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as in the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war, which shall obliterate not only the remains of slavery but all other obstacles to a free democratic evolution that have grown up in its wake.

Yet who realizes the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid.

(7) Anna Strunsky, The Masses (July 1917)

Who that ever knew him can forget him (Jack London), and how will life ever forget one who was so indissolubly a part of her? He was youth, adventure, romance. He was a poet and a social revolutionist. He had a genius for friendship. He loved greatly and was greatly beloved. But how fix in words that quality of personality that made him different from everyone else in the world? How convey an idea of his magnetism and of the poetic quality of his nature? He is the outgrowth of the struggle and the suffering of the Old Order, and he is the strength and the virtue of all its terrible and criminal vices. He came out of the Abyss in which millions of his generation and the generation preceding him throughout time have been hopelessly lost. He rose out of the Abyss, and he escaped from the Abyss to become as large as the race and to be identified with the forces that shape the future of mankind.

His standard of life was high. He for one would have the happiness of power, of genius, of love, and the vast comforts and ease of wealth. Napoleon and Nietzsche had a part in him, but his Nietszchean philosophy became transmuted into Socialism--the movement of his time - and it was by the force of his Napoleonic temperament that he conceived the idea of an incredible success, and had the will to achieve it. Sensitive and emotional as his nature was, he forbade himself any deviation from the course that would lead him to his goal. He systematized his life. Such colossal energy, and yet he could not trust himself! He lived by rule. Law, Order and Restraint was the creed of this vital, passionate youth. His stint was a thousand words a day revised and typed. He allowed himself only four and one-half hours of sleep and began his work regularly at dawn for years. The nights were devoted to extensive reading of science, history and sociology. He called it getting his scientific basis. One day a week he devoted to the work of a struggling friend. For recreation he boxed and fenced and swam--he was a great swimmer--and he sailed--he was a sailor before the mast--and he spent much time flying kites, of which he had a large collection. Like Zola's, his first efforts were in poetry. This no doubt was the secret of the Miltonic simplicity of his prose which has made him the accepted model for pure English and for style in the universities of this country and at the Sorbonne. He had always wanted to write poetry, but poets proverbially starved - unless they or theirs had independent incomes--so poetry was postponed until that time when his fame and fortune were to have been made. Fame and fortune were made and enjoyed for over a decade, but yet the writing of poetry was postponed, and death came before he had remembered his promise to himself. Death came before he had remembered many other things. He was so hard at work--so pitifully, tragically hard at work, and it was a fixed habit by now.

(8) Jack London, letter to Cloudesley Johns (17th October, 1900)

A young Russian Jewess of San Francisco and myself have often quarrelled over our conceptions of love. She happens to be a genius. She is also a materialist by philosophy, and an idealist by innate preference, and is constantly being forced to twist all the facts of the universe in order to reconcile herself with her self. So, finally, we decided that the only way to argue the question out would be by letter.

(9) Jack London, letter to Elwyn Irving Hoffman (6th January, 1901)

I should like to have you meet Miss Anna Strunsky some time. She is well worth meeting.... She has her exoteric circles and her esoteric circles - by this I mean the more intimate and the less intimate. One may pass from one to the other if deemed worthy.... She loves Browning. She is deep, subtle, and psychological. She is neither stiff nor formal. Very adaptive. Knows a great deal. Is a joy and delight to her friends. She is a Russian, and a Jewess, who has absorbed the Western culture, and who warms it with a certain oriental leaven.

(10) Anna Strunsky, unpublished manuscript written in about 1915.

During the first few clays of my stay Mrs. London was very cordial and manifested great interest in our work, but, after a stay of five days, I became convinced that, for some reason, Mrs. London had begun to dislike me. She said nothing of any importance to make me feel out of place, but, judging from several little occurrences, I decided it was best for me to leave the London home. I carried out my resolve and left Piedinont, much against Mr. London's will.

(11) William English Walling, letter to Elias Strunsky (22nd April, 1906)

Anna and I begin to see our lives together in a clearer light. We are talking of our love as much as ever but we begin to speak of our lives too now. This means some very great changes on the part of both. Neither of our lives followed ordinary channels and the adjustment means a great deal. Often it is the woman that does most of the adjusting. With us it is not so. Anna is a personality and a personage in her work and the beautiful and noble influence she must have on the world means as much to me as it does to her. To-day for the first time I have even urged some of her work on her-though I know that must usually be left to her own conscience and inspiration. But I can, must and will help her. I am sufficiently differently constituted to do this and too sympathetic to utter a word that might hinder her in any way.

(12) William English Walling, letter to Elias Strunsky (22nd April, 1906)

We at once discovered, to our amazement, that Springfield had no shame." English wrote later. He and Anna were treated to "all the opinions that pervade the South-that the negro does not need much education, that his present education even has been a mistake, that whites cannot live in the same community with negroes except where the latter have been taught their inferiority, that lynching is the only way to teach them, etc." They even interviewed loan of Arc, one Kate Howard, who proudly said that she drew her inspiration from the South and showed off the buckshot wounds in her arms."

(13) Anna Strunsky, diary entry (12th September, 1916)

The last remark English made last night in bed was "Who ever got any service out of you?"

"What about my serving the babies day and night,"' I remonstrated and I might have added had I not followed my new plan of avoiding as much as possible personal conversation, even when it begins most pleasantly because lie always makes it end speedily in disaster - I might have added "I have served all my life unstintingly - when I taught English to foreigners for nothing all through my girlhood, when I sat up nights correcting other people's articles and stories, when I helped workingmen friends prepare for Regents exams, when I nursed momma, suffered because I was not allowed to do more for my motherless nieces; when in the Socialist Party, I did endless drudgery like being secretary of the Central Committee for over 2 years, and on other committees to which I gave my precious time - time for which my soul and my young fiery senses had other uses altogether. I have given, given, given and now in my babies I give a thousand fold more than ever." . . .

So this morning he refers to his leaving himself free to go or not to go to Boston. "I never tie myself up, it I can help it."

"That's splendid," I say to him. "I always tie myself up. I love freedom, but I have so many duties always."

"Well," he says deprecatingly, "You are like my father." I remonstrate. "I am anything but rigid in my plans; I have always broken my own appointments with myself, in order to keep the last least appointment with everybody. I lose my freedom through being so social, father through being so set on his own ways he tics himself up. I let others tie me up."

"You," says English, "are neither social nor individual. The one who possesses you gets nothing out of you, for you are tied up to the first person that comes along."

This is what I call a thought to cheer me on the way, to start the day upon.

(14) William English Walling, letter to Anna Strunsky (March, 1917)

Of course I think your proposal to attack in the back those who are giving up their lives for democracy, peace, and anti-militarism is criminal to the last degree. But the world is moving in spite of all you do to help the militarists and reactionaries. You are their accomplice and neither I nor mankind, nor the genuine idealists and revolutionaries of the world will ever forget or forgive what your kind has said and done in this great hour. If I fight it will be against the traitors to internationalism - I trust you will not be among them.

(15) Anna Strunsky, letter to William English Walling (21st March, 1917)

Not being a Junker you cannot turn me into one by saying so. It is as just to call my opposition to war Junkerism as it would be for me to say that because you do not always oppose war that you are cruel and blood-thirsty... by torturing and slaying people known to mankind!

You are not a militarist, and I am not a Junker.

A Revolutionist believes in the people and opposes the established order - my faith in the people and opposition to establishment law and order are deep and integral with my whole being. I am not a Junker because I not only give my consent to the rioters of the streets of Petrograd for what they did, but had I not you and our children I would not have hesitated, even at this distance to join them and fall by their side for a regenerated Russia. As it is, rich and wonderful as my life is with you and my children I do not at all feel that I belong wholly to myself and the time may come when I, the most passionate lover of life ever born, may go out to meet death for my Cause - as gallantly as any soldier ever did - but I will make sure that it is my Cause and not the Cause of my enemy.

Some day you will understand me as well as I understand you and then we will laugh together at our past sufferings. That is my day and night dream. It lies in your power to make it come true.

I have had a happy birthday.

I have capitulated to your point of view about this War. What else can we do with the enemy at the door of the Russian Revolution but give him battle and rout him? Until the German people revolt we have to repel their advance upon freedom and democracy with the edge of the sword....

I am forced to descend from my height "Above the Battle" freely to adopt new processes of thought and feeling altogether from those that have guided me for two and a half years. But you cannot dream how it tortures me to have been weak and sick all day to consent to war! I do finally "vote the money and the men" but I do not expect to survive it. In a sense I have already failed to survive it - so much has fallen together in me and died since this morning when my new conception was borne in upon me.

Ever since Rosalind English was born I have seen everybody as a little baby shining on a pillow or on a mother's breast; I have had a mother's tenderness towards the world of men and women; I could always see everybody as they were born to be, not as they were. I feel as if this, my motherhood, were slain this morning when I read the papers and read of the German danger to Russia and when I vicariously flew to arms.... You are more fortunately constituted than I am. You are never divided against yourself. Whatever you think is right and best you have strength for.

(15) Emma Goldman, Mother Earth (June, 1917)

The black scourge of war in its devastating effect upon the human mind has never been better illustrated than in the ravings of the American Socialists, Messrs. Russell, Stokes, Sinclair, Walling, et al.... As to English Walling, he was the reddest of the red. Though muddled mentally he was always at white heat emotionally as syndicalist, revolutionist, dissenter, etc.

With Charles Edward Russell as the conferee of Root, English Walling is the colleague of the New York Times, and Stokes, Simons, Sinclair, Poole, etc. are still waiting for the reward from Washington....

One might overlook the renegacy of a Charles Edward Russell. Nothing else need ever be expected from a journalist. But for men like Stokes and Walling to thus become the lackeys of Wall Street and Washington, is really too cheap and disgusting.

(16) Walter Weyl, Tired Radicals (1921)

I once knew a revolutionist who thought that he loved Humanity but for whom Humanity was merely a club with which to break the shins of the people he hated. He hated all who were comfortable and all who conformed. He hated the people he opposed and he hated those who opposed his opponents in a manner different from his. Zeal for the cause was his excuse for hating, but really he was in love with hate and not with any cause.

The war came, and this vibrant, humorless man, this neurotic idealist who was almost a genius, found a wider vent for his emotion. His hatred, without changing its character, changed its incidence. He learned to hate Germans, Bolshevists, and radicals. He completed the full circle and soon was consorting most incongruously with those whom he had formerly attacked. Today nothing is left of his radicalism or his always leaky consistency; nothing is left but his hatred. At times he hates himself. He would always hate himself could he find no one else to hate. He is becoming half-reactionary, half-cynical. He will end - But who knows how anyone will end?

(17) Anna Strunsky, diary entry (27th September, 1933)

I was wrong when I fell in love with him and began my life with him. I was never safe in his hands. He worked against me in the dark with my children, his mother, so passionately dear to me, my friends and family. He did worse - he worked against me in the dark with himself, in his own heart, for he never gave me a chance to explain, to defend myself.

(18) James Boylan, Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998)

Hutchins Hapgood... paid conventional tribute to Anna's sincerity and constancy, but he implied her ineffectuality as well, with the inevitable insinuation that she had been much diminished by her marriage.

It was true that she had fallen far short of her aspirations. Although she never renounced her faith in a vaguely cooperative, utopian socialism, doctrine hardly played a greater role in her later life than, say, theology among suburban Christians. Once she had made her true lifetime commitment, to marriage, she retained her freedom of opinion but gave up freedom in her economic environment. She lacked the will and the urgent circumstances of the women she portrayed in her account of the revolution to make her own life truly revolutionary.