George Bellows

George Bellows, the son of a building contractor, was born in Columbus, Ohio on 19th August, 1882. At Ohio State University (1901-1904) Bellows was a talented baseball player but his first love was art and he moved to New York City without graduating.

Bellows studied at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri, leader of what became known as the Ashcan School. He was also taught by John Sloan. In 1906 he rented a studio and began painting scenes of everyday urban life. He also taught art at the Arts Students League.

Bellows developed a strong social conscious and in 1911 began contributing pictures to the radical journal, The Masses. Although rarely paid for his work, Bellows got the opportunity to work with other left-wing artists such as John Sloan, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Alice Beach Winter, Mary Ellen Sigsbee, Cornelia Barns, Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent, Art Young, Robert Minor, Lydia Gibson, K. R. Chamberlain, Hugo Gellert and Maurice Becker.

Bellows were deeply influenced by the events of the First World War and he completed a series of paintings and lithographs on the subject. He also produced 25 illustrations for the The Masses in 1917. This included several anti-war drawings, including the powerful attack on Woodrow Wilson and his Espionage Act, entitled, Blessed are the Peacemakers (July, 1917).

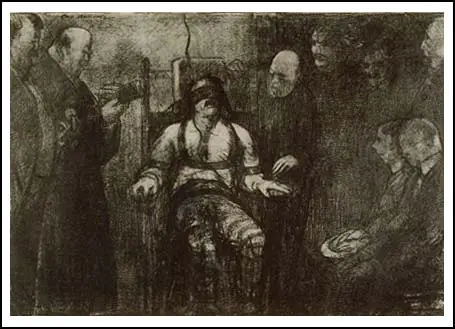

In 1917 Bellows produced the lithograph, Electrocution . He described the print as a "study of one of the most horrible phenomenon of modern society". It was a protest against the sentence of death passed down on Thomas Mooney who had been convicted of being involved in anarchist bombings in San Francisco. As Stephen Coppel has pointed out: "Bellow's horrific subject recalls Goya's etching The Garrotted Man, where the victim is also tied to an upright rectangular block. Bellows equates the fate of those executed by the State with secular martyrdom. Certain devices from religious art are used, such as the signifying of the condemned man by lighter tones, in contrast to the darker tones of his executioners."

In 1919 Bellows moved to the Chicago Art Institute. He also illustrated novels including several by H. G. Wells. The author of The American Scene (2008) has pointed out: "The subjects of his lithographs ranged from sporting themes to images of New York street life, as well as political concerns, while studies of the nude and many portraits dominated the latter years. Bellows worked directly on the lithographic stone for immediacy and speed, and soon showed a mastery of crayon and wash techniques."

George Bellows died on 8th January, 1925 in New York after a neglected attack of appendicitis.

Primary Sources

(1) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1964)

In spite of a ruling by the Attorney General that "the constitutional right of free speech, free assembly, and petition exist in wartime as in peacetime," nearly two thousand men and women were jailed for their opinions during the First World War, their sentences running as high as thirty years.

The Espionage Act, signed by Wilson one month after our entrance into the war, although it contained no press censorship clause, and was ostensibly designed to protect the nation against foreign agents, established three new crimes which made it dangerous to criticize the war policy and impossible to voice the faintest objection to conscription.

A subsequent amendment known as the Sedition Act, defined as seditious, and made punishable, all disloyal language and attacks on the government, the army, the navy, or the cause of the United States in the war. Under this act it became a crime to write a "disloyal" letter, or an anti-war article which might reach a training camp, or express anti-war sentiments to an audience which included men of draft age, or where the expression might be heard by ship-builders or munition-makers.

In our June and July numbers (of The Masses) we had two anti-war cartoons by Boardman Robinson: a picture of Uncle Sam in chains and handcuffs, "All ready to fight for liberty," and one of Jesus Christ being dragged in on a rope by an idiotic recruiting officer. George Bellows contributed another Jesus, in stripes now, with ball and chain and a crown of thorns: "The prisoner used language tending to discourage men from enlisting in the United States army: "Thou shalt not kill - Blessed are the peacemakers."

(2) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1964)

There was one big difference between the Masses and the Liberator; in the latter we abandoned the pretense of being a co-operative. Crystal Eastman and I owned the Liberator, fifty-one shares of it, and we raised enough money so that we could pay solid sums for contributions.

The list of contributing editors, largely brought over from the Masses, reads as follows: Cornelia Barns, Howard Brubaker, Hugo Gellert, Arturo Giovannitti, Charles T. Hallinan, Helen Keller, Ellen La Motte, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Louis Untermeyer, Charles Wood, Art Young.

Later Claude McKay, the Negro poet, became an associate editor. At a New Year's party in 1921, we elected Michael Gold and William Gropper to the staff - two opposite poles of a magnet: Gropper as instinctively comic an artist as ever touched pen to paper, and Gold almost equally gifted with pathos and tears.

(3) Stephen Coppel, The American Scene (2008)

The subjects of his lithographs ranged from sporting themes to images of New York street life, as well as political concerns, while studies of the nude and many portraits dominated the latter years. Bellows worked directly on the lithographic stone for immediacy and speed, and soon showed a mastery of crayon and wash techniques.