Carl Sandburg

Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois on 6th January, 1878. Sandburg's parents, August and Clara Anderson Sandburg, were Swedish immigrants and at the age of thirteen left school and found work as a labourer. He also worked as a bricklayer and a truck driver.

In 1897 Sandburg became a hobo. Has one biographer has pointed out: "His experiences working and traveling greatly influenced his writing and political views. As a hobo he learned a number of folk songs, which he later performed at speaking engagements. He saw first-hand the sharp contrast between rich and poor, a dichotomy that instilled in him a distrust of capitalism."

After fighting in the Spanish-American War he returned to Galesburg and studied at Lombard College while working as a fireman. He joined the Poor Writers' Club, a literary organization formed by Lombard professor Philip Green Wright. Members met to read and criticize each other's work and Wright immediately recognized Sandburg's talent and encouraged him to continue to write. Wright paid for the publication of Sandburg's first volume of poetry, Reckless Ecstasy, in 1904.

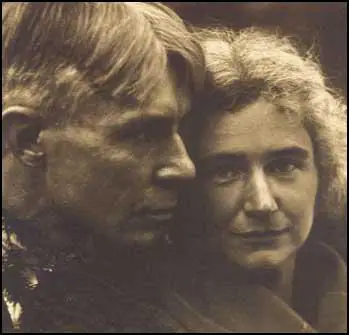

After college, Sandburg moved to Wisconsin, where he worked as an advertising writer. By this time Sandburg was a committed socialist and in 1907 he met Lilian Steichen, the sister of the photographer Edward Steichen, at the Social Democratic Party office. They married the following year and over the next few years Lilian (he called her Paula) gave birth to three daughters (Margaret, Janet, and Helga). Sandburg was also district organizer of the American Socialist Party and in 1910 became secretary to Emil Seidel, the socialist mayor of Milwaukee.

Sandburg became a freelance journalist and eventually was employed by the Chicago Daily News where he met another aspiring writer, Ben Hecht. Other friends during this period included Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, and Edgar Lee Masters. He also produced articles for the International Socialist Review, a journal published by Charles Hope Kerr in Chicago.

In 1911 E. W. Scripps decided to publish a newspaper that was completely free of advertising. The tabloid-sized newspaper was called The Day Book, and at a penny a copy, it aimed for a working-class market, crusading for higher wages, more unions, safer factories, lower streetcar fares, and women’s right to vote. It also tackled the important stories ignored by most other dailies. Carl Sandburg was employed by Scripps in 1913. As a socialist, Sandburg enjoyed working for the The Day Book. According to Duane C. S. Stoltzfus, the author of Freedom from Advertising (2007): "The Day Book served as an important ally of workers, a keen watchdog on advertisers, and it redefined news by providing an example of a paper that treated its readers first as citizens with rights rather than simply as consumers." The newspaper ceased publication in 1917.

Sandburg also contributed poems and articles to The Masses, a socialist journal edited by Max Eastman and run by a co-operative of radical writers and artists. Other members of the group included Floyd Dell, John Reed, William Walling, Sherwood Anderson, Upton Sinclair, Michael Gold, Amy Lowell, Louise Bryant, John Sloan, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

Sandburg's reputation as a major poet was established in 1916 with the publication of Chicago Poems. The book, with its urban themes and Sandburg's use of colloquialism, heralded a new development in American poetry. Sandburg produced several collections of poems over the next fifteen years including Cornhuskers (1918), Smoke and Steel (1920), Slabs of the Sunburnt West (1922) and Good Morning, America (1928).

As well as his poetry, Sandburg is known for series of books on the life of Abraham Lincoln. This included Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926), a book for children, Abe Lincoln Grows Up (1928), Mary Lincoln: Wife and Widow (1932) and Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939). This work won a Pulitzer Prize as did his Complete Poems (1950). Other books include the novel, Remembrance Rock (1948) and an autobiography of his early life, Always the Young Strangers (1952).

Sandburg continued to write poetry and some critics believe that Honey and Salt (1963) published when the author was 85, contains some of his best work.

Carl Sandburg died on 22nd July, 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) Carl Sandburg, International Socialist Review (November 1917)

Thru a steel cage door of the Cook county jail, Big Bill Haywood today spoke the defiance of the Industrial Workers of the World to its enemies and captors.

Bill didn't pound on the door, shake the iron clamps nor ask for pity nor make any kind of a play as a hero. He peered thru the square holes of the steel slats and talked in the even voice of a poker player who may or may not hold a winning hand. It was the voice of a man who sleeps well, digests what he eats, and requires neither sedatives to soothe him nor simulants to stir him up.

The man accused of participation in 10,000 separate and distinct crimes lifted a face checkered by the steel lattice work and said with a slow smile: "Hello, I'm glad to see you. Do you know when they're going to bring the rest of the boys here? We'd like to have them from all over the country together here. It would be homelike for us all to be together."

He was asked about the 10,000 criminal offenses of which the I. W. W. is accused.

"I don't see where they can scrape up 10,000 offenses unless they claim that we circulated 10,000 copies of Pouget's book on sabotage." This with a half smile, and then more intensely:

"Ten thousand crimes! If they can make the American public or any fair minded jury believe that, I don't see how they'll do it. Why, they can't put their fingers on one single place where we have hampered the government in carrying on the war.

"The I. W. W. has done nothing on the war one way or another. It is true we have called strikes, but they were not aimed at stopping the war. Look! In one industry where a strike was called they could have paid workmen $10 a day and then made fat profits. The I. W. W. has been fighting and will keep on fighting for higher wages to pay for a higher cost of living.

"Eggs awhile ago were two for a nickel. Now they're a nickel apiece. A porkchop costs double what it used to. It takes a week's pay of a lumberjack to buy a wool shirt."

"Thousands of married men with families belong to the I. W. W. Milk has gone up for them. At 13 cents a quart they can't buy milk for their babies unless they get more money as wages. Read the testimony federal investigators took up in the Mesaba range. It's conditions and not philosophy that makes the I. W. W."

The checkered face in the steel slats and electric light kept a perfect calm. Where LaFollette is explosive and Mayor Thompson overplausible and grievous, Haywood takes it easy. He discusses the alleged 10,000 crimes with the massive leisure of Hippo Vaughn pitching a shut-out.

"You are charged with burning wheat fields," he was reminded.

"I deny it absolutely. Why should workmen burn up their own employment? They would be fools."

"You are accused of driving spikes into spruce trees needed for war airplanes."

"Deny it absolutely. And get this, boy: Not a dirty German dollar has ever come into our hands that we know of. Go back thru our speeches and literature and you will find that a year ago, two years ago and before the war ever started we were in favor of slashing the kaiser's throat. Every dollar we've got now and every dollar the organization will get comes from workingmen."

(2) Carl Sandburg, Paula (April 1908)

Woman of a million names and a thousand faces,

I looked for you over the earth and under the sky.

I sought you in passing processions

On old multitudinous highways

Where mask and phantom and life go by.

In roaming and roving, from prairie to sea,

From city to wilderness, fighting and praying,

I looked.

Dusty and wayward, I was the soldier,

Long-sentinelled, pacing the night,

Who heard your voice in the breeze nocturnal,

Who saw in the pine shadows your hair,

Who touched in the flicker of vibrant stars

Your soul!

When I saw you, I knew you as you knew me.

We had known far back in the eons

When hills were dust and the sea a mist.

And toil is a trifle and struggle a glory

With You, and ruin and death but fancies,

Woman of a million names and a thousand faces.

(3) Floyd Dell wrote about discovering the work of Carl Sandburg while the literary editor of the Chicago Evening Post in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933)

I met Carl Sandburg, and he read some of his poems from manuscript. They were all impressionistic, misty, soft-outlined, delicate; I remember liking particularly the one about the fog that "comes on little cat feet". Carl Sandburg had not struck yet the note he was soon to strike in Chicago Poems.