Graham Stokes

James Graham Stokes, the son of Anson Phelps Stokes, was born in New York City on 18th March, 1872. The family was extremely rich. His father was a multimillionaire banker but the main wealth came from his great-grandfather, Thomas Stokes, the founder of Phelps, Dodge & Company.(1)

Stokes was educated at Yale University and after graduating in 1892, studied for a medical degree at Columbia University. This was achieved in 1896 but he never worked as a doctor. Inspired by the activities of Jane Addams he became a strong supporter of the University Settlement on the Lower East Side. (2)

James Boylan, the author of Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998), has pointed out: "James Graham Phelps Stokes... brother of the architect, Newton... was a member of one of the city's old and wealthy mercantile families; he had to look after family businesses, but his heart was with New York's social and reform enterprises, which placed him on more boards and committees than he could efficiently serve. The Stokeses were particularly important to the University Settlement; in addition to Newton's role, his sisters were part-time volunteers, and Graham himself was a member of the governing council." (3)

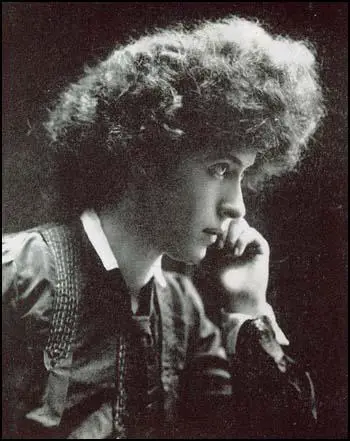

In 1903 Graham Stokes was interviewed by Rose Pastor, a journalist working for the Jewish Daily Forward. Rose Pastor was very impressed with what Stokes had to say and became a volunteer worker at the settlement. The couple were married on 18th July 1905 and moved to a house in Greenwich, Connecticut.

In September 1905, the couple joined with Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Clarence Darrow, William English Walling , Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Leonard D. Abbott, Mary Ritter Beard, Crystal Eastman and Florence Kelley to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. An original statement was published that stated: "The undersigned, regarding its aims and fundamental principles with sympathy, and believing that in them will ultimately be found the remedy for many far-reaching economic evils, propose organizing an association, to be known as the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, for the purpose of promoting an intelligent interest in Socialism among college men, graduate and undergraduate, through the formation of study clubs in the colleges and universities, and the encouraging of all legitimate endeavors to awaken an interest in Socialism among the educated men and women of the country." (4)

In 1906 Stokes joined the Socialist Party of America. Other members included Eugene Debs, Victor Berger, Ella Reeve Bloor, Emil Seidel, Daniel De Leon, Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, William Z. Foster, Abraham Cahan, Sidney Hillman, Morris Hillquit, Walter Reuther, Bill Haywood, Margaret Sanger, Florence Kelley, Mary White Ovington, Helen Keller, Inez Milholland, Floyd Dell, William Du Bois, Hubert Harrison, Upton Sinclair, Agnes Smedley, Victor Berger, Robert Hunter, George Herron, Kate Richards O'Hare, Helen Keller, Claude McKay, Sinclair Lewis, Daniel Hoan, Frank Zeidler, Max Eastman, Bayard Rustin, James Larkin, William English Walling and Jack London.

In May 1907, Stokes replaced Jack London as president of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Over the next few years the ISS took up a lot of his time and made several lecture tours. The main objective of the organization was to encourage study and discussion of socialism in colleges. Stokes was successful with forming branches of the ISS at Harvard University, Princeton University, Bernard College, New York University Law School and the University of Pennsylvania.

First World War

Most socialists in the United States opposed American involvement in the First World War. However, Graham Stokes, along with his friends, William English Walling, Jack London, Charles Edward Russell, John Spargo and Upton Sinclair, thought that President Woodrow Wilson should send troops to fight the German Army in Europe. Stokes began to attack those in the the American Socialist Party who opposed the war as really being secret supporters of Germany. Emma Goldman wrote to Anna Strunsky, the wife of Walling: "I hope you and the children are well and that English is not quite as rabid on the war question as in the past. It is absolutely inexplicable to me how revolutionists will become so blinded by the very thing they have been fighting for years." (5)

The men feared that the Provisional Government in Russia would negotiate a peace settlement with Germany. Stokes, Sinclair, Russell and Walling sent a telegram to Alexander Kerensky, the Minister of War, warning against a separate peace. (6) William B. Wilson, Secretary of Labor, suggested to President Wilson that Walling should be sent to Petrograd to negotiate with Kerensky. "I know of no Socialist in this country who has been more in touch with the Socialistic group of Russia or understands them better than Mr. Walling." (7)

Emma Goldman was furious with Stokes and other pro-war socialists and wrote in Mother Earth: "The black scourge of war in its devastating effect upon the human mind has never been better illustrated than in the ravings of the American Socialists, Messrs. Russell, Stokes, Sinclair, Walling, et al.... As to English Walling, he was the reddest of the red. Though muddled mentally he was always at white heat emotionally as syndicalist, revolutionist, dissenter, etc... One might overlook the renegacy of a Charles Edward Russell. Nothing else need ever be expected from a journalist. But for men like Stokes and Walling to thus become the lackeys of Wall Street and Washington, is really too cheap and disgusting." (8)

Social Democratic League

Graham Stokes and his left-wing friends who argued for intervention on the side of the Allies formed the Social Democratic League of America (SDLA). Early members included William English Walling, John Spargo, Upton Sinclair, Charles Edward Russell, Algie Simons, William James Ghent, Allan L. Benson, Frank Bohn, Emanuel Haldeman-Julius and Alexander Howat. Stokes claimed that the SDLA had a membership of 2,500. However, Kenneth E. Hendrickson, has argued that outside the leadership "the organization must be said to have existed on paper only." (9)

One of the main objectives was to join forces with pro-war forces in Britain. Spargo, who had been born in England, visited London and had a meeting with Henry Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation. Although the Labour Party had given support of the war, and its leader, Arthur Henderson, was a member of the government, and in August, 1917, he made a speech in favour of the proposed Stockholm Peace Conference. Spargo was also concerned about the growth in support for Ramsay MacDonald and his peace group.

It was not long before William English Walling began falling out with other leaders of the SDLA. He objected to the idea that John Spargo should become president of the organisation. He particularly disagreed with Spargo's tolerant position on wartime dissent. Strokes tried to negotiate with Walling about his relationship with Spargo but ended up frustrated with Walling's inability to compromise. Stokes told Walling: "You sometimes make it terribly hard for your friends to work with you." (10) Spargo eventually resigned from the SDLA accusing Walling of believing that "practically all of the men in the Socialist movement of the different countries are, to his mind, pro-Germans and pacifists, peace-at-any-price men." (11)

Rose Pastor Stokes and the War

Rose Pastor Stokes, like most members of the Socialist Party of America was completely opposed to American involvement in the First World War. In 1917 Rose was arrested and charged under the Espionage Act. She was found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison for saying, in a letter to the Kansas City Star, that "no government which is for the profiteers can also be for the people, and I am for the people while the government is for the profiteers."

At the end of the war Rose Pastor Stokes was released from prison. Her experiences moved her to the revolutionary left. The right-wing leadership of the Socialist Party of America opposed the Russian Revolution. On 24th May 1919 the leadership expelled 20,000 members who supported the Soviet government. The process continued and by the beginning of July two-thirds of the party had been suspended or expelled.

Some of these people, including Rose Pastor Stokes, Jay Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Benjamin Gitlow, Charles Ruthenberg, Mikhail Borodin, William Dunne, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Louis Fraina, Ella Reeve Bloor, Juliet Poyntz, Nathan Silvermaster, Jacob Golos, Claude McKay, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, decided to form the Communist Party of the United States. Within a few weeks it had 60,000 members whereas the Socialist Party of America had only 40,000.

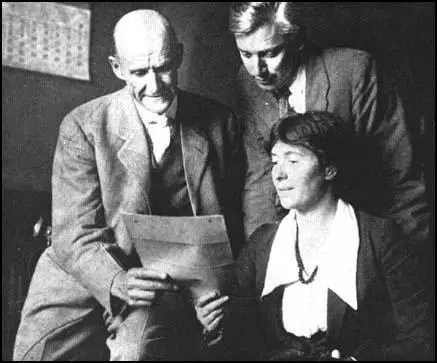

Graham Stokes did not share his wife's communist beliefs. Rose suggested they had become "friendly enemies". In 1925 her husband brought a petition for divorce on grounds of misconduct. He won a decree and four years later married a Greenwich Village teacher, Issac Romain.

Graham Phelps Stokes died in 1960.

Primary Sources

(1) James Boylan, Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998)

The last to come, even more belatedly than English, was the one celebrity among Hunter's crop: James Graham Phelps Stokes, brother of the architect, Newton. Graham, as he was known, was a member of one of the city's old and wealthy mercantile families; he had to look after family businesses, but his heart was with New York's social and reform enterprises, which placed him on more boards and committees than he could efficiently serve. The Stokeses were particularly important to the University Settlement; in addition to Newton's role, his sisters were part-time volunteers, and Graham himself was a member of the governing council. Although he had lived at the settlement once before, the press viewed his return as remarkable and some what amusing. An out-of-town newspaper poked fun at him: "not even the dinner party among the smart set at Newport last summer, when a trained monkey was the guest of honor, aroused more interest." Indeed, settlement residents - particularly male residents in a field dominated by women - were in danger of being seen as unmanly, as "exquisites."

(2) Emma Goldman, Mother Earth (June, 1917)

The black scourge of war in its devastating effect upon the human mind has never been better illustrated than in the ravings of the American Socialists, Messrs. Russell, Stokes, Sinclair, Walling, et al.... As to English Walling, he was the reddest of the red. Though muddled mentally he was always at white heat emotionally as syndicalist, revolutionist, dissenter, etc... One might overlook the renegacy of a Charles Edward Russell. Nothing else need ever be expected from a journalist. But for men like Stokes and Walling to thus become the lackeys of Wall Street and Washington, is really too cheap and disgusting.

(3) James Boylan, Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998)

The celebrated American-dream marriage between wealthy Graham Stokes and Rose Pastor, the one-time immigrant cigarmaker, was ruptured by the war. Graham Stokes took the lead in organizing the prewar socialists. Rose Pastor initially followed him out of the Socialist Party, but soon regretted her decision and then metamorphosed after the authorities blunderingly indicted her under the Sedition Act for a mildly critical speech on war profiteers. She ultimately became a pioneer in the budding American Communist Party. The political division between them, and its personal accompaniments (she wrote to Anna that Graham's "puritanism... made what came inevitable") set them irrevocably on the road to divorce, which took place in 1925.

References

(1) Arthur Zipser and Pearl Zipser, Fire and Grace: The Life of Rose Pastor Stokes (1989) page 28.

(2) The New York Times (28th November, 1902)

(3) James Boylan, Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998) page 57

(4) Max Horn, The Intercollegiate Socialist Society (1979) pages 9-10

(5) Emma Goldman wrote to Anna Strunsky (2nd June, 1915)

(6) Ronald Radosh, American Labor and United States Foreign Policy (1969) pages 73-77

(7) William B. Wilson message sent to President Woodrow Wilson (30th April, 1917)

(8) Emma Goldman, Mother Earth (June, 1917)

(9) Kenneth E. Hendrickson, The Pro-War Socialists, the Social Democratic League, and the Ill-Fated Drive for Industrial Democracy in America, 1917-1920, Labor History, vol. 11, no. 3 (Summer 1970), page 315.

(10) Graham Stokes, letter to William English Walling (16th August, 1917

(11) John Spargo, letter to Graham Stokes (18th September, 1918)