Ella Winter

Leonore (Ella) Wertheimer, the daughter of Adolph Wertheimer and Freda Lust Wertheimer, was born Melbourne, Australia, in 1898. Rosa had been born in 1895 and Rudi in 1897. Ella later wrote: "I was an avid tomboy, full of energy, climbing the highest branches, dreaming wild adventures to share with my gentle brother, who was just a year older... Rudi and I shared everything. Having learned to read at four, I could read aloud to him as we lay on our stomachs on the nursery floor."

When she was at junior school she experienced Anti-Semitism. When she asked her mother what was happening, she replied: "It's time for us to tell you, it wasn't untrue, we were Jewish but we had you baptized when you were born, and Father and I were, too. So we are not Jewish now... We did it because there was so much hatred of Jews in Germany. We thought, in a new country one should make a fresh start. Why should one suffer disabilities needlessly? Since neither Father nor I have any religion, why should you children suffer possible disadvantages and discrimination, especially in another country where no one knows us or our background?"

The family changed its name to Winter and moved to London in 1910. Ella attended the North London Collegiate School. "Teachers played an important role in our school lives... I developed a really serious crush that lasted the rest of school, when I venerated Miss Eleanor Doorly, a very tall, slender, blond-haired woman, with large features and limpid gray eyes. She had long slender hands, which she used as she read aloud verse or parts of plays; it was she who discovered for me the Brownings, Shelley, Coleridge, Addison.... When it was my turn to sit next to Miss Doorly at lunch, I suffocated and afterward suffered tortures because I hadn't known what to say."

While she was at school she discovered the work of Oscar Wilde: "I approved of every argument in The Soul of Man Under Socialism and recited all of The Ballard of Reading Gaol. How dreadfully they treated him! I treasured my volumes in their pale-blue bindings and asked only for Wilde as presents. I stood up for him against all comers; my friend had gone to jail, unfairly, I thought, and I was on his side." After reading The Soul of Man Under Socialism Ella considered herself a socialist.

On the outbreak of the First World War Ella Winter volunteered for war work: "During my last school summer vacation, sixteen of us went farming as war work. Debenham (the large British department store) owned farms in Dorsetshire, and we were to replace farmers who could then go to war. We were promised newly built stables to live in and would be paid fourpence a day... It wasn't quite as pictured. Our lodgings were stables, but cold, bare, with stone floors and walls, tiny bunks jammed together, no electric light, no furniture, and no privacy. We were also underfed. Ravenous from the unaccustomed physical labour, we had to write home for food parcels."

Marion Phillips, knew the Winter family when they lived in Melbourne. Phillips was now living in London. "We all admired her extravagantly - her brilliant mind and effectiveness as a speaker, her activities as suffragist, pacifist, labour organizer... It was a red-letter day for us all when Marion came. She was striking-looking, with black hair, small hands and feet, intense brown eyes - and a stout, uncorseted, ungainly body, which one forgot in the acute discussions she always brought into being. I sat on a hassock, ears and eyes glued to her, drinking in what she said about events, political personalities - she knew everyone - and policies. She made public questions so alive and fascinating that I am sure politics must fill my world; Marion lived as I wanted to live, I would pattern my career on hers. I would not need to marry, any more than she had. My life, like hers, would be in my work."

Ella Winter studied at the University of London and the London School of Economics. Her tutors included Harold Laski ("always invigorating and original, his acute mind could penetrate all one's defenses and make one feel small"), R. H. Tawney ("analyzed the acquisitive society and the economic role of religion in our world"), Sidney Webb ("short, stubby... with squat brown beard and a lisp, delved into his enormous array of facts and the panorama of colonial history), L. T. Hobhouse ("huge, lionlike... examined mind and morals evolving"), Graham Wallas ("his lectures dealt with a newspaper's everyday items"), Clement Attlee ("rather unimpressive... explained the usefulness of charity and took us to the slums") and Lilian Knowles ("a stout woman lecturer who looked like a provincial housewife, revealed to me the economic underpinnings of history").

Winter later admitted that all the writers she admired were "politically minded". This included H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy, Arnold Bennett, Henry Nevinson, H. N. Brailsford, Henry J. Massingham. She added that Granville Barker and Lillah McCarthy "were explosive off stage or on". Winter observed that most of the "best journalists... held socialist or near-socialist views; hardly an intelligent person did not, it seemed."

In 1918 her tutor, Graham Wallas, told Ella that his friend, Professor Felix Frankfurter, was coming to London. "A good friend of mine has come to London on a highly confidential mission and asks me to suggest someone to help him... Felix Frankfurter is a professor at the Harvard Law School and Chairman of the War Labour Policies Board in America, and is here to learn what he can from England's experience. Would you like to work for him."

Winter met Frankfurter at Claridge's Hotel. "He was a short, mercurial man, with glasses and a cleft chin, who smiled, talked in quick staccato phrases, flung questions at one, while attending to twenty other matters at the same time. His smile showed a row of dazzling teeth. Even at rest he seemed in motion. He was warm, friendly, trusting, and assumed so immediately and unquestionably that I would do this job, indeed that I could do anything, that doubt, fear, hesitation vanished."

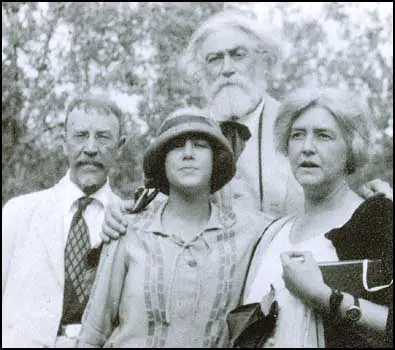

As a research assistant and secretary for Frankfurter, she attended the Versailles Peace Conference in December 1918. Frankfurter asked her to take a message to Lincoln Steffens. "He's a great wit, Steffens is, fond of saying things differently. He's an American newspaperman, much older than you, in his early fifties; he muckraked our cities, knows a lot about politics. You can learn from him, he'll give you a different picture than you got at the London School of Economics." Ella Winter later recalled: "The man was not tall, but he had a striking face, narrow, with a fringe of blond hair, a small goatee, and very blue eyes, and he stood there smiling. The face had wonderful lines... There was something devilish - or was it impish? - in the way this figure stood grinning at me."

Winter recalled that Felix Frankfurter seemed to know everyone at the conference. "Frankfurter had a foothold, or at least a toe-hold, it seemed, in about every delegation. He knew everyone and heard everything. People smiled when they talked of Felix - everybody called him that, so I adopted the habit, but not to his face. He was a magnet attracting politicians and statesmen, labor leaders, diplomats. As I went about his interests on practically a daily Cook's tour of the Peace Conference, I found friends, colleagues, and ex-students of his in almost every office. His name was an open sesame."

Frankfurter also introduced her to Prince Feisal and T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia): "The young, beautiful Prince Feisal was always followed by his group of tall, imposing, silent Arabs in long white robes and head dress, and by his shadow, Colonel T. E. Lawrence, also in native dress. Lawrence was short and fragile-looking, with a delicate, poetic face, but he appeared as much at home with the desert Bedouins and the prince he seemed so attached to as with European diplomats. Felix was as much intrigued by Lawrence's role in all the Middle Eastern politics as with his romantic appearance." Frankfurter told Winter: "Use every opportunity to meet people in person. The English are not very enterprising. You with your zip and energy belong to the United States: you ought to go there, but take my counsel now, use every chance to make personal contacts. They are what count in life. You never know when one may become important."

After her return to London she finished her studies worked for the Committee on Nationalization. An active member of the Labour Party, between 1920 and 1923 she was a member of the Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliamentary Labour Party. During this period she became close friends with Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb, Marion Phillips, Bertrand Russell and Josiah Wedgwood.

Ella Winter attempted to become a journalist. She was turned down by the Daily News because she was "too young and inexperienced". George Lansbury, the editor of the Daily Herald, offered her a job writing about "fashions or cooking". She rejected the idea and accepted a post teaching at the London School of Economics. She also lectured on behalf of the Workers' Educational Association (WEA) "explaining to tired clerks and office workers the magnificent benefits of socialism and nationalization, which they could not have cared less about".

At this time William Heinemann asked Winter to translate a German best seller, The Diary and Letters of Otto Braun. He was a poet and scholar who had been killed during the First World War. The preface was written by Havelock Ellis and Winter visited him a few times: "He was an astonishing old man, extremely tall and imposing, with a large head, white hair, and a bushy square beard. He lived alone in a small flat and, to my surprise, made the tea and carried in the tray." Ellis told her: "My wife lives in another flat, we feel that's better for our relationship." Winter pointed out: "When he discussed marriage, I kept very still lest he stop, but I was uncomfortable because he kept his eyes glued on the opposite wall and did not look at me. He developed this habit, I supposed, when he interviewed women about their sex lives for his Psychology of Sex. Presumably one talked more freely that way, but it gave me an eerie feeling. He did not ask me about my sex life. I was rather hurt."

In the 1922 General Election Ella agreed to help H. G. Wells, the Labour Party candidate for London University. One of those who helped him in his campaign was Ella Winter. She later recalled in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "The constituency consisted of London University teachers and students anywhere in the world, present and past; the campaign was carried out mainly by mail. I had known Wells slightly, but never before seen him troubled about the effects of his well-known unconventional behavior. Had we not regarded him as the apostle of women's rebellion and women's freedom? I was disillusioned when he wondered whether he ought to send out a letter justifying, possibly excusing, those actions. I was also surprised to find how little he knew of, and how childish he seemed about, practical politics." The campaign was unsuccessful and Wells only won 19% of the vote.

Whenever Lincoln Steffens came to London he spent a great deal of time with Ella Winter. After he returned from the Soviet Union, where he interviewed Lenin he said to Bernard Baruch, "I have seen the future and it works." Steffens admitted that "it was harder on the real reds than it was on us liberals". For example Emma Goldman, told him that she was strongly opposed to the communist government. "Emma Goldman, the anarchist who was deported to that socialist heaven, came out and said it was hell. And the socialists, the American, English, the European socialists, they did not recognize their own heaven. As some will put it, the trouble with them was that they were waiting at a station for a local train, and an express tore by and left them there. My summary of all our experiences was that it showed that heaven and hell are one place, and we all go there. To those who are prepared, it is heaven; to those who are not fit and ready, it is hell."

Winter became increasingly radicalised during this period. A visit from Marion Phillips, who was now a senior figure in the Labour Party, ended up in a heated discussion about the Russian Revolution. Winter later described the incident: "When the conversation turned to the Russian Revolution and Bolshevism, the evening, to my dismay, exploding into astonishing hostility and bitterness from Marion Phillips. Like the official Labour Party, she was implacably opposed to the Russian Revolution, but it did not occur to me that her enmity and personal rudeness may have been partly due to her realization that she was losing me."

In 1924 Ella Winter agreed to live with Steffens, thirty-two years her senior. They moved to Paris and spent some time with William Christian Bullitt and Louise Bryant, who had just got married. Bryant was the widow of John Reed. Winter later wrote in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "We saw much of Louise Bryant and Billy Bullitt, Louise very pregnant in an Arabian Nights maternity gown of black and gold that I thought could have been worn by a Persian queen. Billy hovered over her like a mother hen." A daughter, Anne Moen Bullitt, was born in 24th February, 1924.

The couple also spent time with Ernest Hemingway, a young writer he discovered. According to Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Among the younger men Steffens saw in Paris, Ernest Hemingway appeared to him to have the surest future, the most buoyant confidence, and the best grounds for it." Steffens told Ella Winter: "He's fascinated by cablese, sees it as a new way of writing." Winter explained: "Stef loved anything new, original, or experimental, and he especially cherished young people. He was sending Hemingway's stories to American magazines, and they were coming back, but this did not alter his opinion." Steffens told anyone who would listen: "Someone will recognize that boy's genius and then they'll all rush to publish him." Hemingway also encouraged Winter to write: "It's hell. It takes it all out of you; it nearly kills you; but you can do it."

Ella Winter became pregnant. She later explained, "Steff wanted the baby, but not to be again a married man... Illegitimacy, so dread a concept to me, meant nothing to him; in fact, he regarded it as rather an advantage." He argued "love-children have always been the best, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Erasmus" and added "I'm an anarchist, I don't want the law to dictate to me." However, he changed his mind and they married in Paris when she was six months pregnant. Their son Pete Steffens was born in San Romeo, in 1924.

By this stage of his career Steffens found difficulty in finding magazines willing to publish his work. He believed it was because he had campaigned against the imprisonment of James and Joseph McNamara, convicted of the Los Angeles Times Bombing. Steffens complained: "Editors are afraid of me since I took the McNamaras' part ten years ago. I was condemned by everybody." He wrote an article, Oil and Its Political Implications , that he was very pleased with but could not find a publisher for it. He told Ella, "I don't seem able to state my truths so that they'll be accepted. I must find a new form."

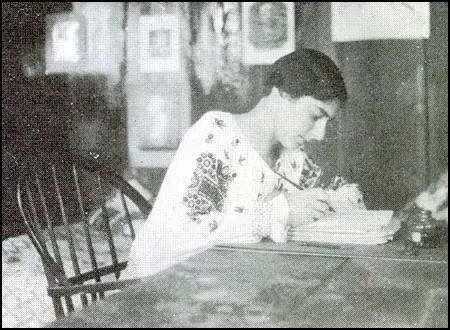

Although they did not want his articles several publishers had offered him contracts to write his autobiography. He had talked about it, but the job seemed too vast. Steffens was also a perfectionist. According to Ella he "wrote on small pad pages by hand, wrote and rewrote" unwilling to leave a paragraph "until the prose sings". He insisted that "I can't leave a paragraph until it's perfect. That's how I trained myself to write."

In 1927 Winter and Steffens moved to the U.S. and settled in Carmel, California (Winter became a naturalized American citizen in 1929). Winter wrote: "Carmel had been created when a real-estate man decided to enhance the value of the land by developing it and offering free lots to any artist who would build. Among early settlers were George Sterling, the California poet, Jack London, Mary Austin, Ambrose Bierce... Now Carmel was an artists' colony, with painters, writers, musicians, photographers living in little wooden or stone cottages." During this period Winter and Steffens befriended a number of artists, journalists, and political figures, including Albert Rhys Williams, John Steinbeck, Robinson Jeffers, Harry Leon Wilson and Marie de L. Welch.

In 1930 Ella Winter visited the Soviet Union with a group of American politicians including Burton Wheeler, Bronson Cutting, Robert A. Taft and Alben Barkley. She wrote to Steffens in August: "The chief trouble with some Americans is that they bring their own economic ideas and judge Russia by them... I'm beginning to see that economic laws are dependent on time and place, too, and are relative, not absolute... Moscow is torn up, new paving being hurried through before winter. Everywhere new buildings - it's like New York. These new buildings are modern - of the sort that excited us so in Los Angeles... My room at the Grand Hotel is on the Square and the trams are noisy. Wheeler says there were practically no trams in 1923 - and you should just see the numbers of automobiles."

Winter later wrote about her first time to the Soviet Union: "The trip was a revelation. However much I had heard, I had not pictured the reality. These were still in many ways the early revolutionary days, with the fire and excitement, the hope and enthusiasm of the new young world. People were poor, certainly, poorly dressed, living in a single room, short of many things, with the shop windows exhibiting cardboard pictures of meat, vegetables, and eggs rather than the real thing. Yet millions of children, workers' children who before had had nothing and could hope for nothing, were eating, singing, dancing, holding hands in the new nursery schools, freed from squalor and disease and neglect. Health and education, literacy and knowledge were replacing the results of centuries of poverty and ignorance." Lincoln Steffens did not share Ella's enthusiasm for the Soviet form of government. He never joined the American Communist Party but Ella became an active member.

Steffens's memoirs, Autobiography, was published in April 1931. It was a great success and as Ella Winter has pointed out: "He had to talk everywhere, at bookshops, lunches, meetings, and autograph copies even for the salesgirls in bookstores... I couldn't help feeling proud. The six years' doubts, agonies, despairs had their reward. I felt Stef had done what he sought to do, showed in a wealth of anecdote and incident what he had learned and unlearned in the course of his life... He had told the stories he had been telling me for years and which had so opened my eyes." Steffens told Ella: "I guess I'm a success. I guess I'll go down in history now."

In 1931 Ella Winter visited Germany. She managed to obtain an interview with General Erich Ludendorff. He asked her what magazines she was working for. Winter replied, Harper's Magazine and Scribner's Magazine. Ludendorff commented: "In the hands of Freemasons, both of them; of course you know that... The Freemasons, the Bolsheviks, the world international financiers are trying to rule the world... They and the Jews." Winter later pointed out: "I had not heard such talk outside a mental hospital and did not know how to proceed with a supposedly rational political interview."

Winter also returned to the Soviet Union and was impressed by the progress the government was making: "As on my earlier visit, I was particularly concerned with the changes in the status of women, one of the most underprivileged sections of the old society. I found that part of the new Russian plan was the determined drive to get women out of the kitchen and into public life, the farm, industry, the professions. Soviet women were judges, doctors, engineers, editors, bricklayers, and were learning to utilize their new independence."

However, she found the country struggling to modernize. She wrote to Lincoln Steffens: "In the midst of the new and visionary I found an inefficiency that could drive one to desperation. I suppose it's because they've had to be so hurriedly trained and have no experience, and centuries of apathy to overcome, and perhaps just because they can get jobs whether they're good or not. But it takes days to get anything done. They never make an appointment, they tell you to come and then they'll arrange when you must must telephone again to ask for an appointment. Lifts are always out of order; a current anecdote has a 'lift factory' entirely devoted to manufacture of the notices LIFT OUT OF ORDER".

Ella Winter saw Maxim Gorky lecture on literature to students during a visit in 1932: "He (Gorky) was like a stringy poplar tree, tall and thin and frail, his face, with its big walrus mustache, paper yellow like old parchment. He looked as if he might topple over. But he talked for an hour, about writing and literary problems, and held his audience; some inner strength seemed to support him."

Winter's first book, Red Virtue: Human Relations in the New Russia, was published in 1933. It received some good reviews. The Chicago Tribune wrote that "the book becomes a presentation of the Russian Communist as a stumbling human being, as anxious as the next person to solve the urgent problem of human happiness... and an admirable study of people actually trying to change the processes of human nature, and who think they have." The New Yorker believed the "author maintains a degree of objective detachment that would do credit to the most austere sociologist".

Ella Winter went to interview Harry Bridges during the waterfront strike in 1934: "In San Francisco I went first to the longshoremen's headquarters on the Embarcadero and found Harry Bridges, the voluble and tough union leader, a wire spring of a man with a narrow, sharp-featured, expressive face, popping eyes, and strong Australian accent. He heartily greeted a fellow Australian, a limey, as he dubbed me, though I was a little taken aback at my first real taste of a worker's intemperate language." Bridges told her that previous strikes had been crushed and a company union set up: "The seamen couldn't get together because they were divided into so many crafts, machinists, cooks, stewards, ships' scalers, painters, boilermakers, the warehousemen on the docks, and the teamsters who hauled the goods. The bosses want to keep it that way so they can make separate contracts for each craft and in each port, which weakens our bargaining position. We're asking for one coastwise contract, from Portland to San Pedro, for the whole industry, and a raise too, but the most important thing we want is a hiring hall under the men's control."

Steffens also supported the strikers. On 19th July 1934 he wrote to Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor: "There is hysteria here, but the terror is white, not red. Business men are doing in this Labor struggle what they would have liked to do against the old graft prosecution and other political reform movements, yours included... Let me remind you that this widespread revolt was not caused by aliens. It takes a Chamber of Commerce mentality to believe that these unhappy thousands of American workers on strike against conditions in American shipping and industry are merely misled by foreign Communist agitators. It's the incredibly dumb captains of industry and their demonstrated mismanagement of business that started and will not end this all-American strike and may lead us to Fascism."

Peter Hartshorn, the author of I Have Seen the Future: A Life of Lincoln Steffens (2011), has argued: "The final agreement saw concessions made by both sides, with the result being the continued emergence of an organized labor voice in California and nationwide, an achievement in which Steffens took some consolation. Perkins herself did not ignore Steffens, inviting him the following year to attend a San Francisco meeting of West Coast leaders."

Steffens continued to help young writers. He wrote to his friend, Sam Darcy on 25th February, 1936, about the work of John Steinbeck and his novel, In Dubious Battle: "His novel is called In Dubious Battle, the story of a strike in an apple orchard. It's a stunning, straight, correct narrative about things as they happen. Steinbeck says it wasn't undertaken as a strike or labor tale and he was interested in some such theme as the psychology of a mob or strikers, but I think it is the best report of a labor struggle that has come out of this valley. It is as we saw it last summer. It may not be sympathetic with labor, but it is realistic about the vigilantes."

Lincoln Steffens, aged seventy, became very ill that summer. He was diagnosed as suffering from arteriosclerosis, but refused to leave his home in Carmel, California. He told his doctor: "I'd rather die sooner than leave my own home". He died on 9th August 1936. According to Ella Winter his last words were "No, no. I can't..."

Winter remained active in politics and was a founder member of the League of American Writers (LAW), an organization that attempted "to get writers out of their ivory towers and into the active struggle against Nazism and Fascism." She also wrote articles for the Manchester Guardian, The Nation, New Republic, New York Times, Daily News, Scribner's Magazine, Collier's Magazine and the Ladies' Home Journal.

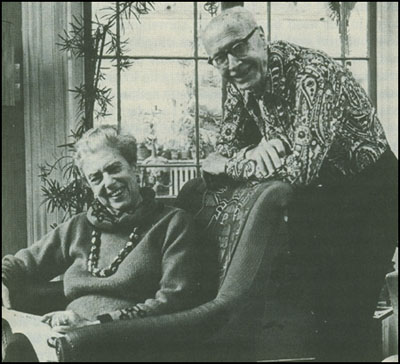

At a conference in November 1937, Winter met the writer, Donald Ogden Stewart. She was introduced as the widow of Lincoln Steffens. Stewart later commented: "I dimly remembered from my youth Steffens' muckraking articles in father's bound volumes of McClure's magazine, and I awaited gray hair and a few sad but brave wrinkles. To my astonishment, there came to the front of the platform a handsome middle-aged brunette who had the most extraordinary black eyes, alternately luminous and flashing as she spoke in a charming British voice." In her speech she "welcomed especially the humorists who had come from Hollywood, because what the Movement needs is humor, humor and more humor," and added "Dorothy Parker and Donald Ogden Stewart in one sentence can help us more than a thousand jargon-filled pamphlets."

Ella Winter described their first meeting in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "He was tall and slender and very graceful, with blond hair and blue eyes that very often held a puckish look like that of a wise and naughty child. Humorous and gentle, shy and warmhearted, Don was strangely untouched by the Hollywood he had lived and worked in for some years.... He had lately become passionately interested in what was happening politically in Europe, the United States, Germany, California; he read hungrily, and was fascinated by my experiences."

In 1938 Stewart's wife, Beatrice Ames Stewart, divorced him to marry Count Ilya Andreyevich Tolstoy. "Bea meanwhile had successfully obtained a Florida divorce and I was free to marry Ella. There was, however, one small hitch: She wasn't in any particular hurry to get married. Her hesitancy arose partly out of concern over presenting without careful preparation her eleven-year-old son, Pete Steffens, with a stepfather. The relationship between Pete and Lincoln Steffens had been extremely tender and close." The couple eventually married in 1939.

In August 1939, Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact. Soon afterwards Hitler gave orders for the invasion of Poland. This forced Neville Chamberlain to declare war on Nazi Germany, therefore starting the Second World War. Three weeks later Stalin ordered the Red Army to invade Poland from the east, meeting the Germans in the centre of the country. The leaders of the American Communist Party accepted Stalin's message that the war was not against fascism but just another "imperialist war between capitalistic nations".

Under the influence of the American Communist Party, the League of American Writers supported Stalin's new foreign policy. Most members left the organisation in disgust but Winter and Stewart remained loyal. As Stewart explained in By a Stroke of Luck (1975): "I just couldn't be unfaithful to my friends or my side. So I didn't denounce any Communist-controlled organizations of which I was president or to which my name was helpful. My growing doubts about the American Communist Party's interpretation of Marxism didn't affect my belief in the superior wisdom of the remote Soviet Union which, being so distant, in no way challenged my personal ethics."

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan, Winter and Stewart were recruited by Archibald MacLeish, head of the Office of War Information. This included writing speeches for "War Administration big shots" and scripts for war propaganda radio programmes. Stewart was especially proud of a script he wrote for a radio documentary: "I chose as my subject an actual happening in a small Ohio town where, in a truly joint effort, each person contributed labor according to his or her ability. For the first few weeks, the war effort became democratic in the sense in which I hoped all of America might some day become, that is, of people working together in equality and for each other instead of competing in a rat race for financial security and status." However, it was considered too left-wing and was never broadcast.

In May 1944 Ella Winter was contacted by Ted Thackrey, the editor of the New York Post, and invited to be their Moscow correspondent. Winter agreed and in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "I went everywhere: to hospitals and farms, libraries, churches, rehabilitation homes for the blind and mutilated, psychiatric clinics, orphanages, the ballet, the children's theater. I discovered that when the Nazis entered a village, they hanged librarians and schoolteachers first. We were taken on trips to Leningrad, Minsk, Tallin in Estonia, and the Volga-Don canal. I interviewed tank drivers, farmers, women fighter pilots and snipers - even the famous girl sniper Pavlichenko, who had shot sixty men. I talked to an eighteen-year-old red-cheeked peasant girl who had fled from a German prison and spent three terrified weeks on the road."

On her return to the United States she published I Saw the Russian People (1946). As Donald Ogden Stewart pointed out: "It was an honest, moving account of the heroism of the common people during the war; it was equally honest about her discovery of certain disquieting developments since her original visit in the early thirties, which she had told about in her Red Virtue. Her book was unfortunately completed in the face of the growing fears and apprehensions of the Cold War. The heroism of Russian resistance to Hitler and the hopes of the war-time alliance were beginning to be overwhelmed by the post-war actions and reactions of East and West."

In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Harnett, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party. The list included Winter and Donald Ogden Stewart. A free copy was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past. Winter and Stewart were now blacklisted.

Dorothy Parker and Alan Campbell were also on the list. The couple left Hollywood and moved back to New York City. In April 1951, Parker and Campbell were visited by two FBI agents. They asked if they knew Stewart, Winter, Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Ella Winter and John Howard Lawson and if they had attended meetings of the American Communist Party with them. The agents reported: "She (Parker) was a very nervous type of person... During the course of this interview, she denied ever having been affiliated with, having donated to, or being contacted by a representative of the Communist Party."

Winter and Stewart moved to England and rented the former house of Ramsay MacDonald at 103 Frognal, Hampstead. According to Norma Barzman, the actress, Katharine Hepburn, helped the Stewarts to renovate the house: "Its condition was so wretched the owners, the former prime minister's family, felt they couldn't ask for rent. Katharine Hepburn, the Stewarts' bosom friend for years, took one look at the house, said it was beautiful, came over every day for six weeks with a packed lunch from the Connaught Hotel, and helped Ella fix it up."

Over the next few years Ella Winter published The World of Lincoln Steffens (1962) and an autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963).

Donald Ogden Stewart died in London on 2nd August 1980. Ella Winter died two days later.

Primary Sources

(1) Donald Ogden Stewart, By a Stroke of Luck (1975)

One Saturday morning, in the middle of November, I was in my office at Metro engaged in doing three rather contradictory things at once. I was trying to think of a scene for a film, the name of which I can no longer remember; I was reading the second volume of a history of the Russian Revolution by Leon Trotsky; and I was listening to the Yale-Princeton game on my radio. Usually a high-salaried screen writer doesn't go within miles of any studio on Saturday, but I was anxious to show Bernie Hyman that my political activities were not interfering with my devotion to good old M-G-M. Suddenly, just as Yale was on the eight yard line, the telephone rang and I cursingly answered. It was Dorothy Parker, and she wondered if I could fly up to San Francisco that afternoon to a Conference of Western Writers. Yale fumbled and lost the ball, and I said I would.

On the plane were fellow writers, Joel Sayre, Humphrey Cobb, Dorothy and her husband Alan Campbell. The conference was distinctly Left Wing, being run by sort of a Western branch of the League of American Writers, an organization set up in New York the year before "to get writers out of their ivory towers and into the active struggle against Nazism and Fascism." I didn't know anybody in the hall where the meeting was being held, or any of the speakers, but I was particularly impressed by the speech of a man who spoke with a sort of Cockney accent and whose name was Harry Bridges. He had been introduced amid tremendous enthusiasm as a Labor Leader, and I thrilled at the thought of such a man speaking to writers. This was getting closer to the real thing.

Then, with equal enthusiasm, there was introduced "the courageous untiring fighter against Nazism whom we all know, the widow of the great Lincoln Steffens, our beloved Ella Winter." I dimly remembered from my youth Steffens' muckraking articles in father's bound volumes of McClure's magazine, and I awaited gray hair and a few sad but brave wrinkles. To my astonishment, there came to the front of the platform a handsome middle-aged brunette who had the most extraordinary black eyes, alternately luminous and flashing as she spoke in a charming British voice. Her words were charming, too; she "welcomed especially the humorists who had come from Hollywood, because what the Movement needs is humor, humor and more humor," and added "Dorothy Parker and Donald Ogden Stewart in one sentence can help us more than a thousand jargon-filled pamphlets." By this time I was ready to help "our beloved Ella" do anything.

After the meeting we all met in a bar where she introduced me to Bridges, who instantly won my heart with his dry humor, his good sense, and his ability to drink large quantities of bourbon. Then Ella (she was "Ella" by then) took Harry and Dotty and the rest of our good old Hollywood delegation to the apartment of Paul Smith, a friendly young newspaper editor whose walls featured admiringly autographed photos of Lincoln Steffens and Herbert Hoover.

Next day came more thrills for the romantic convert when at Humphrey Cobbs' request we were taken over to San Quentin prison to interview Tom Mooney. The afternoon was featured by another meeting of the Western writers at which I pledged Hollywood's undying help, was promptly attacked as "just a giver of lavish publicity-seeking dances" by a furious all-out left wing writer and defended most ably by an even more furious flashing-eyed beauty named Ella Winter.

In Lincoln Steffens' Autobiography (which I promptly read) Ella is described as a "dancing girl," and I decided to see if he was as wise in that department of life as he was about politics. A month later Ella made a flying visit to Hollywood to raise money for a weekly magazine she was editing and after a try-out or two at the Trocadero I was able to give the Autobiography - and her - my unreserved admiration. This seemed to compensate somewhat for reports from Broadway that my play The New House was proving even more difficult to sell than Insurance. No reasons were give by Leland Hayward, other than "They just don't seem to care for the theme."

(2) Ella Winter, And Not to Yield (1963)

I do not suppose I could have been drawn to anyone who did not share my larger concerns. Don had become newly aware in the past few years of social questions, and it was all still fresh and challenging to him. He was tall and slender and very graceful, with blond hair and blue eyes that very often held a puckish look like that of a wise and naughty child. Humorous and gentle, shy and warmhearted, Don was strangely untouched by the Hollywood he had lived and worked in for some years. He was a gifted and humorous writer and talker, and he loved gaiety, cheerful people - a "gala" atmosphere, as he called it. He had lately become passionately interested in what was happening politically in Europe, the United States, Germany, California; he read hungrily, and was fascinated by my experiences. Radicals at this time were frequently charged with "boring from within," and when eventually Don and I began seeing more of each other, our friends were gaily malicious at what they thought of as the double success of my efforts -one was supposed only to influence ideas, not the holder of them.

Don was born in Columbus, Ohio, and he had characteristic American traits, from an outward conformism to a consuming interest in the World Series. But he had a rare courage and independence of mind, and a stubborn, almost puritan, integrity, which withstood all blandishments. (I soon dubbed him John Knox.) When he believed in something, he felt he must act on his beliefs. He was making speeches for the Hollywood anti-Nazi movement in out-of-the-way halls or on the piers of Venice or Santa Monica, unostentatiously and with an unconcern for possible effects on his Hollywood position. As the movement grew in the film colony, he was called on more and more to chair meetings - his spontaneous humor made him a witty, popular speaker and toastmaster-and to sign an increasing number of protests and petitions. His sponsorship of so many committees and delegations gave rise to a satiric story: when President Roosevelt awoke in the morning, he would ring for his orange juice, his coffee, and "the first eleven telegrams from Donald Ogden Stewart."

(3) Donald Ogden Stewart, By a Stroke of Luck (1975)

Bea meanwhile had successfully obtained a Florida divorce and I was free to marry Ella. There was, however, one small hitch: She wasn't in any particular hurry to get married. Her hesitancy arose partly out of concern over presenting without careful preparation her eleven-year-old son, Pete Steffens, with a stepfather. The relationship between Pete and Lincoln Steffens had been extremely tender and close. So when I started on Love Affair, Ella brought Pete out and we took up trial residence in a small Westwood village house. Ames and Duck were entered at a boarding school in the Ojai Valley.

Beatrice had become the Countess Tolstoy. The only remaining problem of the changeover was the outcome of' my efforts to convert the son of Lincoln Steffens to the Stewart brand of paternity.

The problem was solved in a rather unexpected way. One evening in early March, 1939, Ella was helping Pete with his lessons when he suddenly looked up at her and asked: "Say, Mom, how long is it going to be before I can call this guy dad?" That did it, and we were married the next day at the court house in the nearby town of Ventura. That afternoon I made a speech before a Negro Youth Club and in the evening Joan Payson gave us a party at the Beachcombers, a new restaurant featuring a rum drink called a "Zombie."

(4) Ella Winter, And Not to Yield (1963)

I went everywhere: to hospitals and farms, libraries, churches, rehabilitation homes for the blind and mutilated, psychiatric clinics, orphanages, the ballet, the children's theater. I discovered that when the Nazis entered a village, they hanged librarians and schoolteachers first. We were taken on trips to Leningrad, Minsk, Tallin in Estonia, and the Volga-Don canal. I interviewed tank drivers, farmers, women fighter pilots and snipers - even the famous girl sniper Pavlichenko, who had shot sixty men. I talked to an eighteen-year-old red-cheeked peasant girl who had fled from a German prison and spent three terrified weeks on the road.

"And what are you going to do now you're back?" I asked her. She lifted her weeping face, threw her head back, and in a sobbing voice cried, "I'm going back to my farm and I'm going to double my potato production!"

In a Leningrad orphanage I picked up a tiny three-year-old who had lost everyone - one of five thousand in that home. She put her arms tight around my neck. "Adopt me," she wailed, "please, please adopt me!"

One little boy told me he had "written Daddy again and again, and given the letter to a postman." It was addressed only by name, and when they asked where they'd find his father, the little boy said, "Oh, you'll know him easily enough from the hole in his shoe." And a child under drugs in a clinic, reliving the death by torture of his mother and a cherished uncle, cried out despairingly: "Grandmother, your heart can break with sorrow." The woman doctor found herself weeping as she wrote.

We saw fifty-seven thousand German prisoners marched silently through Moscow, with dulled, frightened eyes, their feet in rags, broken glasses lacking earpieces. People lining the route were silent. "Poor devils," one old woman said, "they couldn't help it, I don't suppose; they were forced into it like all the rest." When we interviewed the German prisoners and asked them why they had committed their outrages, they, one after the other, like mechanical toys, replied, "Befehl ist Befehl " ("Orders are orders").

Day after day in Russian cities or the rutted roads of villages I saw feats of endurance hard to conceive. In one village, where no men were left, the old women lived in holes underground, and smoke came out of the earth. I called on the mother of Zoya, the nineteen-year-old girl whom the Germans had tortured and hanged naked in the snow for her part in a partisan raid. The mother was in agony, but dared not give in. "If only my boy Shura lives!" she cried, "if only he be spared." He wasn't.

I went to a hospital where Doctor Frumkin, the surgeon who had cared for Lenin after he was shot, was constructing new sexual organs for mutilated soldiers. He told me about one young man so encouraged at the prospect of not being a eunuch that, under the guise of visiting a dying grandmother, he took a weekend off with his nurse "and tore my whole six-month surgical work to pieces." The doctor grinned. "But the young man didn't care, he was so jubilant that it had worked!"

© John Simkin, April 2013