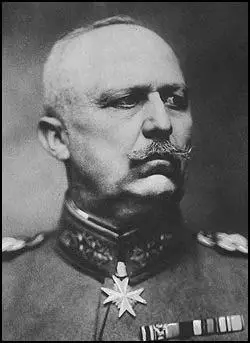

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Ludendorff, the third of six children, was born near Posen on 9th April 1865. His father, August Wilhelm Ludendorff (1833-1905), was a landowner. He was educated at the Cadet School at Plön. An intelligent student he was placed in a class two years ahead of his actual age group.

In 1885 Ludendorff was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 57th Infantry Regiment. He later served with the 2nd Marine Battalion and the 8th Grenadier Guards. In 1893 he attended the War Academy and the following year was appointed to the General Staff of the German Army. By 1911 he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

Ludendorff worked with General Alfred von Schlieffen on what became known as the Schlieffen Plan. Schlieffen argued that if war took place it was vital that France was speedily defeated. If this happened, Britain and Russia would be unwilling to carry on fighting. Schlieffen calculated that it would take Russia six weeks to organize its large army for an attack on Germany. Therefore, it was vitally important to force France to surrender before Russia was ready to use all its forces.

Schlieffen's plan involved using 90% of Germany's armed forces to attack France. Fearing the French forts on the border with Germany, Alfred von Schlieffen suggested a scythe-like attack through Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg. The rest of the German Army would be sent to defensive positions in the east to stop the expected Russian advance.

Ludendorff used his influence to persuade the Reichstag to increase military spending and to adopt a more agressive foreign policy. This upset the Social Democratic Party and in January 1913 Ludendorff was dismissed from the General Staff and was forced to return to regimental duties and was given the command of the 39th Fusiliers at Dusseldorf.

On the outbreak of the First World War was appointed Chief of Staff in East Prussia. Working with Paul von Hindenburg, commander of the German Eighth Army, Ludendorff won decisive victories over the Russians at Tannenberg (1914) and the Masaurian Lakes (1915).

Paul von Hindenburg replaced Erich von Falkenhayn as Chief of Staff of the German Army in August, 1916. Hindenburg appointed Ludendorff as his quartermaster general. Soon afterwards, Ludendorff and Hindenburg became the leaders of the military-industrial dictatorship Third Supreme Command. Ludendorff supported unrestricted submarine warfare and successfully put pressure on Kaiser Wilhelm II to dismiss those in the armed forces that favoured a negotiated peace settlement.

Ludendorff gradually became the dominant figure in the Third Supreme Command and after the resignation of Theobald Bethmann Hollweg in July, 1917, took effective political, military and economic control of Germany. After the withdrawal of Russia from the war in 1917 Ludendorff was a key figure in the Brest-Litovsk negotiations.

With the Spring Offensive Ludendorff expected to breakthrough on the Western Front. When this ended in failure Ludendorff realised that Germany would lose the war. On 29th September 1918, the Third Supreme Command transferred power to Max von Baden and the Reichstag. By the end of October, Baden's government was strong enough to force Ludendorff's resignation.

After the signing of the Armistice, Ludendorff moved to Sweden where his wrote books and articles claiming that the unbeaten German Army had been "stabbed in the back" by left-wing politicians in Germany. He also published his memoirs, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920).

Fritz Thyssen later recalled: "I went to see Ludendorff chiefly to pay him a call of courtesy, but also in order to discuss with him the great national questions which then preoccupied his mind as much as mine. I deplored the fact that there were not at that time men in Germany whom an energetic national spirit would inspire to improve the situation... He recommended to me in particular the Overland League and, above all, the National Socialist party of Adolf Hitler." Ludendorff told Thyssen: "He (Hitler) is the only man who has any political sense. Go and listen."

Ludendorff eventually returned to Germany where he participated in both the Kapp Putsch (March, 1920) and the Munich Putsch (November, 1923). The following year he became one of the first supporters of the Nazi Party in the Reichstag. Ludendorff was the right-wing Nationalist candidate in the 1925 Presidential Elections but won less than 1 per cent of the vote.

In 1931 Ella Winter visited Germany. She managed to obtain an interview with Ludendorff. He asked her what magazines she was working for. Winter replied, Harper's Magazine and Scribner's Magazine. Ludendorff commented: "In the hands of Freemasons, both of them; of course you know that... The Freemasons, the Bolsheviks, the world international financiers are trying to rule the world... They and the Jews." Winter later pointed out: "I had not heard such talk outside a mental hospital and did not know how to proceed with a supposedly rational political interview."

Erich Ludendorff died on 20th December 1937.

© John Simkin, May 2013

Primary Sources

(1) Eric Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918(1920)

The fifth act of the great drama in Flanders opened on the 22nd October. Enormous masses of ammunition, such as the human mind had never imagined before the war, were hurled upon the bodies of men who passed a miserable existence scattered about in mud-filled shell-holes. The horror of the shell-hole area of Verdun was surpassed. It was no longer life at all. It was mere unspeakable suffering. And through this world of mud the attackers dragged themselves, slowly, but steadily, and in dense masses. Caught in the advanced zone by our hail of fire they often collapsed, and the lonely man in the shell-hole breathed again. Then the mass came on again. Rifle and machine-gun jammed with the mud. Man fought against man, and only too often the mass was successful.

(2) In his autobiography, My War Memories, 1914-1918, Eric Ludendorff wrote about the impact of the Battle of the Somme.

On the Somme the enemy's powerful artillery, assisted by excellent aeroplane observation and fed with enormous supplies of ammunition, had kept down our own fire and destroyed our artillery. The defence of our Infantry had become so flabby that the massed attacks of the enemy always succeeded. Not only did our moral

suffer, but in addition to fearful wastage in killed and wounded, we lost a large number of prisoners and much material.

The most pressing demands of our officers were for an increase of artillery, ammunition, aircraft and balloons, as well as larger and more punctual allotments of fresh divisions and other troops to make possible a better system of reliefs.

The equipment of the Entente armies with war material had been carried out on a scale hitherto unknown. The Battle of the Somme showed us every day how great was the advantage of the enemy in this respect.

When we added to this the hatred and immense determination of the Entente, their starvation-blockade or stranglehold, and their mischievous and lying propaganda, which was so dangerous for us, it was quite obvious that our victory was inconceivable unless Germany and her Allies threw into the scale everything they had, both in manpower and industrial resources, and unless every man who went to the front took with him from home a resolute faith in victory and an unshakable conviction that the German Army must conquer for the sake of the Fatherland. The soldier on the battlefield, who endures the most terrible strain that any man can undergo, stands, in his hour of need, in dire want of this moral reinforcement from home, to enable him to stand firm and hold out at the front.

(3) Erich Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918(1920)

Before all these events the world has stood astonished; it could not believe its eyes when it saw the collapse of this proud and mighty Germany, the terror of her foes. The Entente feared us even in our destruction, and could not take enough advantage of the opportunity to weaken us still further internally by propaganda and by imposing a helots' peace upon us.

Germany, by her own fault, has been brought low. She is no longer a great power; she is not even an independent State, Her present and future existence are in danger.

Out of this world struggle she comes weakened and diminished in every respect, and robbed of districts and peoples which have been hers for generations.

All delusions have vanished, mass suggestion begins to fail. We look into nothingness. Self-deception, empty words, the practice of trusting to others or to phantoms, lip courage, meaning vain promises for the future and weakness in the present; all these will never help us, as they have never helped us in the past.

(4) Eric Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920)

The proud German Army, after victoriously resisting an enemy superior in numbers for four years, performing feats unprecedented in history, and keeping our foes from our frontiers, disappeared in a moment. Our victorious fleet was handed over to the enemy. The authorities at home, who had not fought against the enemy, could not hurry fast enough to pardon deserters and other military criminals, including among these many of their own number, themselves and their nearest friends.

They and the Soldiers' Councils worked with zeal, determination and purpose to destroy the whole military structure. Such was the gratitude of the new homeland to the German soldiers who had bled and died for it in millions. The destruction of Germany's power to defend herself - the work of Germans - was the most tragic crime the world has witnessed. A tidal wave had broken over Germany, not by the force of nature, but through the weakness of the Government, represented by the Chancellor, and the paralysis of a leaderless people.

(5) Eric Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920)

In sharp contrast to the form of defence hitherto employed, which had been restricted to rigid and easily recognised lines of little depth, a new system was devised which, by distribution in depth and the adoption of a loose formation, enabled a more active defence to be maintained. It was, of course, intended that the position should remain in our bands at the end of the battle, but the infantryman need no longer say to himself, 'Here I must stand or fall,' but had, on the contrary, the right within certain limits, to retire in any direction before strong enemy fire. Any part of the line that was lost was to be recovered by counter-attack. The group, on the importance of which many intelligent officers had insisted before the war, now became officially the tactical unit of the infantry. The position of the N.C.O. as group leader thus became much more important. Tactics became more and more individualised. Having regard to the ever more scanty training of our officers, N.C.O.'s and men, and the consequent falling-off in discipline, it was a risky business, of the success of which many eminent soldiers were sceptical, to make ever greater demands on the subordinate leaders, and the individual soldier.

(6) Fritz Thyssen went to see General Erich Ludendorff in October 1923. He wrote about what happened in his book, I Paid Hitler (1941)

I went to see Ludendorff chiefly to pay him a call of courtesy, but also in order to discuss with him the great national questions which then preoccupied his mind as much as mine. I deplored the fact that there were not at that time men in Germany whom an energetic national spirit would inspire to improve the situation.

"There is but one hope," Ludendorff said to me, "and this hope is embodied in the national groups which desire our recovery." He recommended to me in particular the Overland League and, above all, the National Socialist party of Adolf Hitler. Ludendorff greatly admired Hitler. "He is the only man," he said, "who has any political sense. Go and listen to him one day."

I followed his advice. I attended several public meetings organized by Hitler. It was then that I realized his oratorical gifts and his ability to lead the masses. What impressed me most, however, was the order that reigned in his meetings, the almost military discipline of his followers.

(7) Morgan Philips Price, Germany in Transition (1923)

The rump of the old parties is now working in close touch with a new party, the so-called National Socialist Party under Herr Hitler and Herr Eckert, who is organizing under a Fascist banner those elements of the trade unions who are tired of the cowardice of the Social-Democratic leaders. These new groups under the leadership of Hitler and Ludendorff have come out openly for a Fascist dictatorship, and by tactics of provocation of the Socialists and Republican elements in the rest of Germany, and by attacks on Socialist meetings and demonstrations, hope to ferment civil war, leading up to the seizure of power by their armed forces. During the winter of 1922-23, Hitler's storm battalions organized raiding expeditions to the industrial towns of North Bavaria. His plan of campaign is to seize power in North Bavaria, or Frankenland, and use it as a base of operations against Thuringen and Saxony where Social-Democratic governments are in power with the aid of Communist votes. From there the way would be open to the industrial districts of Prussia in the North. Success will very much depend on the goodwill of the German heavy industry trusts who, after the murder of Rathenau, withdrew their financial support from most of these Fascist bodies. But after the French occupation of the Ruhr, the heavy industries began again to support the Bavarian Fascists.

© John Simkin, April 2013