Versailles Treaty

When the Armistice was signed on 11th November, 1918, it was agreed that there would be a Peace Conference held in Paris to discuss the post-war world. Opened on 12th January 1919, meetings were held at various locations in and around Paris until 20th January, 1920.

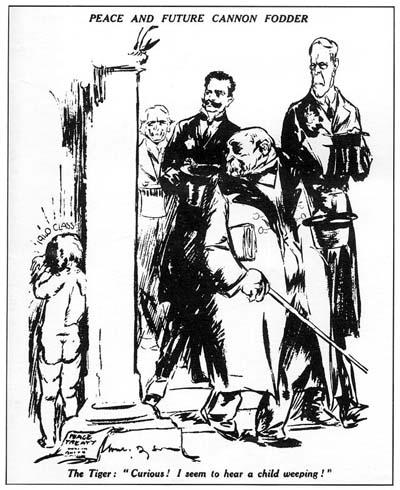

Leaders of 32 states representing about 75% of the world's population, attended. However, negotiations were dominated by the five major powers responsible for defeating the Central Powers: the United States, Britain, France, Italy and Japan. Important figures in these negotiations included Georges Clemenceau (France) David Lloyd George (Britain), Vittorio Orlando (Italy), and Woodrow Wilson (United States).

Wilson wanted to the peace to be based on the Fourteen Points published in October 1918. Lloyd George was totally opposed to several of the points. This included Point II "Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants." Lloyd George saw this as undermining the country's ability to protect the British Empire.

Another issue that worried Lloyd George was Point III: "The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance." His government was split on the subject. Some favoured a system where tariffs were placed on countries outside the British Empire. Lloyd George would also have difficulty in delivering Point IV. "Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety."

Seven of Wilson's points demanded or implied support for "autonomous development" or "self-determination". For example, Point V: "A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the Government whose title is to be determined." This was an attempt to undermine the British Empire. (1)

These measures were also opposed by Georges Clemenceau. He told Lloyd George that if he accepted what Wilson proposed, he would have serious problems when he returned to France. "After the millions who have died and the millions who have suffered, I believe - indeed I hope - that my successor in office would take me by the nape of the neck and have me shot." (2)

While the discussions were taking place, the Allies continued the naval blockade of Germany. It is estimated that by December, 1918, there were 763,000 civilian famine related deaths. (3) Robert Smillie, the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), in June, 1919, issued a statement condemning the blockade claiming that another 100,000 German civilians had died since the armistice. (4)

David Lloyd George admitted that the blockade was killing German civilians and was fermenting revolution, but thought it necessary in order to force Germany to sign the peace treaties: "The mortality among women, children and the sick is most grave and sickness, due to hunger, is spreading. The attitude of the population is becoming one of despair and people feel that an end by bullets is preferable to death by starvation." (5)

Ulrich Brockdorff-Rantzau, the leader of the German delegation, made a speech attacking the blockade. "Crimes in war may not be excusable, but they are committed in the struggle for victory in the heat of passion which blunts the conscience of nations. The hundreds of thousands of non-combatants who have perished since November 11 through the blockade were killed with cold deliberation after victory had been won and assured to our adversaries." (6)

Clemenceau and Lloyd George both hated each other. Clemenceau believed that Lloyd George knew nothing about the world beyond Great Britain, lacked a formal education and "was not an English gentleman". Lloyd George thought Clemenceau a "disagreeable and bad-tempered old savage" who, despite his large head, "had no dome of benevolence, reverence or kindliness". (7)

Raymond Poincare, another French politician, commented that Lloyd George told Clemenceau: "I won't budge, I will act like a hedgehog and wait until they come to talk to me. I will yield nothing. We will see if they can manage without me." Poincare believed that "Lloyd George is a trickster... I don't like being double-crossed. Lloyd George has deceived me. He made me the finest promises, and now he breaks them. Fortunately, I think that at the moment we can count on American support." (8)

Lloyd George told Edward House, a member of the USA's delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, that "he had to have a plausible reason for having fooled the British people about the questions of war costs, reparations and what not... Germany could not pay anything like the indemnity which the French demanded." (9)

David Lloyd George put in a claim for £25 billion of reparations at the rate of £1.2 billion a year. Clemenceau wanted £44 billion, whereas Wilson said that all Germany could afford was £6 billion. On 20th March 1919, Lloyd George explained to Wilson that it would be difficult to "disperse the illusions which reign in the public mind". He had of course been partly responsible for this viewpoint. He was especially worried about having to "face up" to the "400 Members of Parliament who have sworn to exact the last farthing of what is owing to us." (10)

Lloyd George argued that Germany should pay the costs of widows' and disability pensions, and compensation for family separations. John Maynard Keynes, an economist who was the chief Treasury representative of the British delegation, was totally opposed to the idea. (11) He argued that if reparations were set at a crippling level the banking system, certainly of Europe and probably of the world, would be in danger of collapse. (12) Lloyd George replied: "Logic! Logic! I don't care a damn for logic. I am going to include pensions." (13)

Philip Kerr, 11th Marquess of Lothian, also advised Lloyd George against demanding too much from Germany: "You may strip Germany of her colonies, reduce her armaments to a mere police force and her navy to that of a third rate power, all the same if she feels that she has been unjustly treated in the peace of 1919, she will find means of exacting retribution from her conquerors... The greatest danger that I see in the present situation is that Germany may throw in her lot with Bolshevism and place her resources, her brains, her vast organising powers at the disposal of the revolutionary fanatics whose dream is to conquer the world for Bolshevism by force of arms." (14)

When it was rumoured that Lloyd George was willing to do a deal closer to the £6 billion than the sum proposed by the French, The Daily Mail began a campaign against the Prime Minister. This included publishing a letter signed by 380 Conservative backbenchers demanding that Germany pay the full cost of the war. "Our constituents have always expected and still expect that the first edition of the peace delegation would be, as repeatedly stated in your election pledges, to present the bill in full, to make Germany acknowledge the debt and then discuss ways and means of obtaining payment. Although we have the utmost confidence in your intentions to fulfil your pledges to the country, may we, as we have to meet innumerable inquiries from our constituents, have your renewed assurances that you have in no way departed from your original intention." (15)

Lloyd George made a speech in the House of Commons where he argued that it was wrong to suggest that he was willing to accept a lower figure. He ended his speech with an attack on Lord Northcliffe, who he accused of seeking revenge for his exclusion from the government. "Under these conditions I am prepared to make allowance, but let me say that when that kind of diseased vanity is carried to the point of sowing dissension between great allies whose unity is essential to the peace of the world... then I say, not even that kind of disease is a justification for so black a crime against humanity." (16)

Negotiations continued in Paris over the level of reparations. The Australian prime minister, William Hughes, joined the French in claiming the whole cost of the war, his argument being that the tax burden imposed on the Allies by the German aggression should be regarded as damage to civilians. He estimated the cost of this was £25 billion. John Foster Dulles, commented that in his opinion, Germany should only pay about £5 billion. Faced with the possibility of an American veto, the French abandoned their claims to war costs, being impressed by Dulles's argument that, having suffered the most damage, they would get the largest share of reparations. (17)

David Lloyd George eventually agreed that he been wrong to demand such a large figure and told Dulles he "would have to tell our people the facts". John Maynard Keynes suggested to Edwin Montagu that whereas Germany should be required to "render payment for the injury she has caused up to the limit of her capacity" but it was "impossible at the present time to determine what her capacity was, so that the fixing of a definite liability should be postponed." (18)

Keynes explained to Jan Smuts that he believed the Allies should take a new approach to negotiations: "This afternoon... Keynes came to see me and I described to him the pitiful plight of Central Europe. And he (who is conversant with the finance of the matter) confessed to me his doubt whether anything could really be done. Those pitiful people have little credit left, and instead of getting indemnities from them, we may have to advance them money to live." (19)

On 28th March, 1919, Keynes warned Lloyd George about the possible long-term economic problems of reparations. "I do not believe that any of these tributes will continue to be paid, at the best, for more than a very few years. They do not square with human nature or march with the spirit of the age." He also thought any attempt to collect all the debts arising from the First World War would poison, and perhaps destroy, the capitalist system. (20)

Georges Clemenceau made his final appeal to persuade the delegates to impose harsh terms on the Germans. "For many years the rulers of Germany, true to the Prussian tradition, strove for a position of dominance in Europe. They were not satisfied with that growing prosperity and influence to which Germany was entitled, and which all other nations were willing to accord her, in the society of free and equal peoples. They required that they should be able to dictate and tyrannise to a subservient Europe, as they dictated and tyrannised over a subservient Germany... The conduct of Germany is almost unexampled in human history. The terrible responsibility which lies at her doors can be seen in the fact that not less than seven million dead lie buried in Europe, while more than twenty million others carry upon them the evidence of wounds and sufferings, because Germany saw fit to gratify her lust for tyranny by resort to war."

Clemenceau then went on to argue: "Justice, therefore, is the only possible basis for the settlement of the accounts of this terrible war. Justice is what the German Delegation asks for and says that Germany had been promised. Justice is what Germany shall have. But it must be justice for all. There must be justice for the dead and wounded and for those who have been orphaned and bereaved that Europe might be freed from Prussian despotism. There must be justice for the peoples who now stagger under war debts which exceed £30,000,000,000 that liberty might be saved. There must be justice for those millions whose homes and land, ships and property German savagery has spoliated and destroyed. That is why the Allied and Associated Powers have insisted as a cardinal feature of the Treaty that Germany must undertake to make reparation to the very uttermost of her power; for reparation for wrongs inflicted is of the essence of justice." (21)

Keynes argued that it was in the best interest of the future of capitalism and democracy for the Allies to deal swiftly with the food shortages in Germany: "A proposal which unfolds future prospects and shows the peoples of Europe a road by which food and employment and orderly existence can once again come their way, will be a more powerful weapon than any other for the preservation from the dangers of Bolshevism of that order of human society which we believe to be the best starting point for future improvement and greater well-being." (22)

Eventually it was agreed that Germany should pay reparations of £6.6 billion (269bn gold marks). Keynes was appalled and considered that the figure should be below £3 billion. He wrote to Duncan Grant: "I've been utterly worn out, partly by incessant work and partly by depression at the evil round me... The Peace is outrageous and impossible and can bring nothing but misfortune... Certainly if I were in the Germans' place I'd die rather than sign such a Peace... If they do sign, that will really be the worst thing that could happen, as they can't possibility keep some of the terms, and general disorder and unrest will result everywhere. Meanwhile there is no food or employment anywhere, and the French and Italians are pouring munitions into Central Europe to arm everyone against everyone else... Anarchy and Revolution is the best thing that can happen, and the sooner the better." (23)

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28th June 1919. Keynes wrote to Lloyd George explaining why he was resigning: "I can do no more good here. I've on hoping even though these last dreadful weeks that you'd find some way to make of the Treaty a just and expedient document. But now it's apparently too late. The battle is lost. I leave the twins to gloat over the devastation of Europe, and to assess to taste what remains for the British taxpayer." (24)

Eventually five treaties emerged from the Conference that dealt with the defeated powers. The five treaties were named after the Paris suburbs of Versailles (Germany), St Germain (Austria), Trianon (Hungary), Neuilly (Bulgaria) and Serves (Turkey). These treaties imposed territorial losses, financial liabilities and military restrictions on all members of the Central Powers.

The main terms of the Versailles Treaty were:

(1) The surrender of all German colonies as League of Nations mandates.

(2) The return of Alsace-Lorraine to France.

(3) Cession of Eupen-Malmedy to Belgium, Memel to Lithuania, the Hultschin district to Czechoslovakia.

(4) Poznania, parts of East Prussia and Upper Silesia to Poland.

(5) Danzig to become a free city;

(6) Plebiscites to be held in northern Schleswig to settle the Danish-German frontier.

(7) Occupation and special status for the Saar under French control.

(8) Demilitarization and a fifteen-year occupation of the Rhineland.

(9) German reparations of £6,600 billion.

(10) A ban on the union of Germany and Austria.

(11) An acceptance of Germany's guilt in causing the war.

(12) Provision for the trial of the former Kaiser and other war leaders.

(13) Limitation of Germany's army to 100,000 men with no conscription, no tanks, no heavy artillery, no poison-gas supplies, no aircraft and no airships;

(14) The German navy was allowed six pre-dreadnought battleships and was limited to a maximum of six light cruisers (not exceeding 6,100 tons), twelve destroyers (not exceeding 810 tons and twelve torpedo boats (not exceeding 200 tons) and was forbidden submarines.

Edward M. House admitted the Treaty of Versailles was a flawed document: "Looking at the conference in retrospect there is much to approve and much to regret. It is easy to say what should have been done, but more difficult to have found a way for doing it. The bitterness engendered by the war, the hopes raised high in many quarters because of victory, the character of the men having the dominant voices in the making of the Treaty, all had their influence for good or for evil, and were to be reckoned with." (25)

At a meeting of the Union of Democratic Control held on 11th November, 1920, the Treaty of Versailles was attacked by the historian, Richard Tawney: "For every man who a year ago knew and said that the Peace Treaty was immoral in conception and would be disastrous, there are thousands who say it now. Though there seems little to be said about the Treaties which has not been said already, it is nevertheless of immense importance to let public opinion abroad realise that the heartless and cynical politicians who negotiated them do not represent the real temper of Great Britain." (26)

It also came under attack from senior figures in the military who took part in the First World War. General Hubert Gough complained: "It seems to me that the Peace Treaty can be viewed from two points of view, the moral and the purely utilitarian. From either it appears thoroughly bad, and it has failed and must continue to fail to reach any good result, such as all who fought in the war supposed we were to gain. We hoped to establish justice, fair-dealing between nations, and the honest keeping of promises; we thought to establish a good and lasting peace which would, of necessity, have been established on good will. The Peace Treaty has done nothing of the kind." (27)

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Lansing was the American secretary of state during the Paris Peace Conference. He wrote about Georges Clemenceau in his book The Big Four (1922)

Within the council chamber his domineering manner, his brusqueness of speech, and his driving methods of conducting business disappeared. He showed patience and consideration towards his colleagues and seldom spoke until the others had expressed their views. It was only on rare occasions that he abandoned his suavity of address and allowed his emotions to affect his utterances. It was then only that one caught a glimpse of the ferocity of The Tiger.

(2) Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes (2013)

The future life of Europe was not their concern. Its means of livelihood was not their anxiety. Their preoccupations, good and bad alike, related to frontiers and nationalities, to the balance of power, to imperial aggrandisement, to the future enfeeblement of a strong and dangerous enemy, to revenge and to the shifting, by the victors, of their own unbearable financial burdens on to the shoulders of the defeated.

(3) Roy Hattersley, David Lloyd George (2010)

Lloyd George's conduct during the negotiation of the peace treaty is difficult to defend. He went to Paris with no clear idea of what was either desirable for the future peace of the world or necessary to recompense Britain for the cost of the war and neutralise the demands for retribution.He possessed neither a guiding principle nor the full confidence of the politicians on whom he depended. So he veered wildly between attempts to create a new world order and endorsement of a settlement designed to propitiate the vengeful victors, incapacitate "the Prussian war machine" and ensure that Germany was never again a threat to peace. Temperament as well as judgement allowed him only one way of dealing with the popular demand that Germany should pay the full cost of the war. He tried to broker a compromise between reason and prejudice. It was that which made Keynes find `in his company, that flavour of final purposelessness, inner irresponsibility, existence outside or away from Saxon good and evil, mixed with cunning, remorselessness and love of power' which fascinated even his most bitter critics.

It is not necessary to agree with Keynes's bitter analysis of Lloyd George's character to accept that he was temperamentally unsuited to the demands of a long and tedious peace conference. He was not at his best in a council of equals. He liked to be firmly in charge or to lead an open rebellion against the establishment. Paris allowed neither. Yet, because of his domination of his own delegation, history has, rightly, held him responsible for the British position.

(4) Raymond Poincare diary entry (14th March, 1919)

Today Clemenceau is angry with the English, and especially with Lloyd George. - I won't budge," he said, - I will act like a hedgehog and wait until they come to talk to me. I will yield nothing. We will see if they can manage without me. Lloyd George is a trickster. He has managed to turn me into a "Syrian". I don't like being double-crossed. Lloyd George has deceived me. He made me the finest promises, and now he breaks them. Fortunately, I think that at the moment we can count on American support. What is the worst of all is that the day before yesterday, Lloyd George said to me. "Well, now that we are going to disarm Germany, you no longer need the Rhine". I said to Clemenceau: " Does disarmament then seem to him to give the same guarantees? Does he think that, in the future, we can be sure of preventing Germany from rebuilding her army?" "We are in complete agreement," said Clemenceau; " it is a point I will not yield."

(5) Georges Clemenceau, letter to General Henri Mordacq (15th April 1919)

In the last three days, we have worked well. All the great issues of concern to France are almost settled. Yesterday, as well as the two treaties giving us the military support of Britain and the United States in case of a German attack, I obtained the occupation of the Rhineland for fifteen years, with partial evacuation after five years. If Germany does not fulfil the treaty, there will be no evacuation either partial or definitive. At last I am no longer anxious. I have obtained almost everything I wanted.

(6) David Lloyd George, The Truth About the Peace Treaties (1938)

There never was a greater contrast, mental or spiritual, than that which existed between these two notable men. Wilson with his high but narrow brow, his fine head with its elevated crown and his dreamy but untrustful eye - the make-up of the idealist who is also something of an egoist; Clemenceau, with a powerful head and the square brow of the logician - the head conspicuously flat topped, with no upper storey in which to lodge the humanities, the ever vigilant and fierce eye of the animal who has hunted and been hunted all his life. The idealist amused him so long as he did not insist on incorporating his dreams in a Treaty which Clemenceau had to sign.

It was part of the real joy of these Conferences to observe Clemenceau's attitude towards Wilson during the first five weeks of the Conference. He listened with eyes and ears lest Wilson should by a phrase commit the Conference to some proposition which weakened the settlement from the French standpoint. If Wilson ended his allocution without doing any perceptible harm, Clemenceau's stern face temporarily relaxed, and he expressed his relief with a deep sigh. But if the President took a flight beyond the azure main, as he was occasionally inclined to do without regard to relevance, Clemenceau would open his great eyes in twinkling wonder, and turn them on me as much as to say: "Here he is off again!"

(7) Ulrich Brockdorff-Rantzau, speech (7th May, 1919)

We cherish no illusions as to the extent of our defeat, or the degree of our impotence. We know the forces of hatred which confront us here... We are far from seeking to exonerate Germany from all responsibility... but we emphatically combat the idea that Germany, whose people were convinced that they were waging a defensive war, should alone be laden with guilt.

Crimes in war may not be excusable, but they are committed in the struggle for victory in the heat of passion which blunts the conscience of nations. The hundreds of thousands of non-combatants who have perished since November 11 through the blockade were killed with cold deliberation after victory had been won and assured to our adversaries.

(8) Georges Clemenceau, speech at the Paris Peace Conference (16th June 1919)

In the view of the Allied and Associated Powers the war which began on August 1st, 1914, was the greatest crime against humanity and the freedom of peoples that any nation, calling itself civilised, has ever consciously committed. For many years the rulers of Germany, true to the Prussian tradition, strove for a position of dominance in Europe. They were not satisfied with that growing prosperity and influence to which Germany was entitled, and which all other nations were willing to accord her, in the society of free and equal peoples. They required that they should be able to dictate and tyrannise to a subservient Europe, as they dictated and tyrannised over a subservient Germany. Germany's responsibility, however, is not confined to having planned and started the war. She is no less responsible for the savage and inhuman manner in which it was conducted.

Though Germany was herself a guarantor of Belgium, the rulers of Germany violated, after a solemn promise to respect it, the neutrality of this unoffending people. Not content with this, they deliberately carried out a series of promiscuous shootings and burnings with the sole object of terrifying the inhabitants into submission by the very frightfulness of their action. They were the first to use poisonous gas, notwithstanding the appalling suffering it entailed. They began the bombing and long distance shelling of towns for no military object, but solely for the purpose of reducing the morale of their opponents by striking at their women and children. They commenced the submarine campaign with its piratical challenge to international law, and its destruction of great numbers of innocent passengers and sailors, in mid ocean, far from succour, at the mercy of the winds and the waves, and the yet more ruthless submarine crews. They drove thousands of men and women and children with brutal savagery into slavery in foreign lands. They allowed barbarities to be practised against their prisoners of war from which the most uncivilised people would have recoiled.

The conduct of Germany is almost unexampled in human history. The terrible responsibility which lies at her doors can be seen in the fact that not less than seven million dead lie buried in Europe, while more than twenty million others carry upon them the evidence of wounds and sufferings, because Germany saw fit to gratify her lust for tyranny by resort to war.

The Allied and Associated Powers believe that they will be false to those who have given their all to save the freedom of the world if they consent to treat this war on any other basis than as a crime against humanity.

Justice, therefore, is the only possible basis for the settlement of the accounts of this terrible war. Justice is what the German Delegation asks for and says that Germany had been promised. Justice is what Germany shall have. But it must be justice for all. There must be justice for the dead and wounded and for those who have been orphaned and bereaved that Europe might be freed from Prussian despotism. There must be justice for the peoples who now stagger under war debts which exceed £30,000,000,000 that liberty might be saved. There must be justice for those millions whose homes and land, ships and property German savagery has spoliated and destroyed.

That is why the Allied and Associated Powers have insisted as a cardinal feature of the Treaty that Germany must undertake to make reparation to the very uttermost of her power; for reparation for wrongs inflicted is of the essence of justice. That is why they insist that those individuals who are most clearly responsible for German aggression and for those acts of barbarism and inhumanity which have disgraced the German conduct of the war, must be handed over to a justice which has not been meted out to them at home. That, too, is why Germany must submit for a few years to certain special disabilities and arrangements. Germany has ruined the industries, the mines and the machinery of neighbouring countries, not during battle, but with the deliberate and calculated purpose of enabling her industries to seize their markets before their industries could recover from the devastation thus wantonly inflicted upon them. Germany has despoiled her neighbours of everything she could make use of or carry away. Germany has destroyed the shipping of all nations on the high sea, where there was no chance of rescue for their passengers and crews. It is only justice that restitution should be made and that these wronged peoples should be safeguarded for a time from the competition of a nation whose industries are intact and have even been fortified by machinery stolen from occupied territories.

(9) Edward M. House, diary (29th June, 1919)

June 29, 1919: I am leaving Paris, after eight fateful months, with conflicting emotions. Looking at the conference in retrospect there is much to approve and much to regret. It is easy to say what should have been done, but more difficult to have found a way for doing it.

The bitterness engendered by the war, the hopes raised high in many quarters because of victory, the character of the men having the dominant voices in the making of the Treaty, all had their influence for good or for evil, and were to be reckoned with.

How splendid it would have been had we blazed a new and better trail! However, it is to be doubted whether this could have been done, even if those in authority had so decreed, for the peoples back of them had to be reckoned with. It may be that Wilson might have had the power and influence if he had remained in Washington and kept clear of the Conference. When he stepped from his lofty pedestal and wrangled with representatives of other states upon equal terms, he became as common clay.

To those who are saying that the Treaty is bad and should never have been made and that it will involve Europe in infinite difficulties in its enforcement, I feel like admitting it. But I would also say in reply that empires cannot be shattered and new states raised upon their ruins without disturbance. To create new boundaries is always to create new troubles. The one follows the other. While I should have preferred a different peace, I doubt whether it could have been made, for the ingredients for such a peace as I would have had were lacking at Paris

The same forces that have been at work in the making of this peace would be at work to hinder the enforcement of a different kind of peace, and no one can say with certitude that anything better than has been done could be done at this time. We have had to deal with a situation pregnant with difficulties and one which could be met only by an unselfish and idealistic spirit, which was almost wholly absent and which was too much to expect of men come together at such a time and for such a purpose.

And yet I wish we had taken the other road, even if it were less smooth, both now and afterward, than the one we took. We would at least have gone in the right direction and if those who follow us had made it impossible to go the full length of the journey planned, the responsibility would have rested with them and not with us.

(10) Richard Tawney, speech at a Union of Democratic Control (11th November, 1920)

For every man who a year ago knew and said that the Peace Treaty was immoral in conception and would be disastrous, there are thousands who say it now. Though there seems little to be said about the Treaties which has not been said already, it is nevertheless of immense importance to let public opinion abroad realise that the heartless and cynical politicians who negotiated them do not represent the real temper of Great Britain.

(11) Ernest Bennett, speech at a Union of Democratic Control (11th November, 1920)

The fundamental falsehood on which the Versailles Treaty is built is the theory that Germany was solely and entirely responsible for the war. No fair-minded student of the war and its causes can accept this contention; but the propaganda story of Germany's sole guilt has been preached so persistently from pulpit, Press and Parliament that the bulk of our people have come to regard it as an axiomatic truth which justifies the provisions of the most brutal and unjust Treaty in the world's history.

(12) General Hubert Gough, speech at a Union of Democratic Control (11th November, 1920)

It seems to me that the Peace Treaty can be viewed from two points of view, the moral and the purely utilitarian. From either it appears thoroughly bad, and it has failed and must continue to fail to reach any good result, such as all who fought in the war supposed we were to gain. We hoped to establish justice, fair-dealing between nations, and the honest keeping of promises; we thought to establish a good and lasting peace which would, of necessity, have been established on good will. The Peace Treaty has done nothing of the kind.

(12) The Daily Mail journalist, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, was a strong critic of the Versailles Peace Treaty.

If all had worked together as comrades to repair the damage done and to build up better conditions than existed before - had worked at this task without resentment, recognizing that all had been to blame, there would have been employment for all and the promises of a "better world", made so glibly for recruiting purposes, could have been fulfilled. But that called for a clearness of foresight, an honesty of purpose, which the politicians in power at that time did not possess.

(13) John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of Peace (1920)

The Treaty includes no provision for the economic rehabilitation of Europe - nothing to make the defeated Central Powers into good neighbours, nothing to stabilise the new States of Europe, nothing to reclaim Russia; nor does it promote in any way a compact of economic solidarity amongst the Allies themselves; no arrangement was reached at Paris for restoring the disordered finances of France and Italy, or to adjust the systems of the Old World and the New.

It is an extraordinary fact that the fundamental economic problem of a Europe starving and disintegrating before their eyes, was the one question in which it was impossible to arouse the interest of the Four. Reparation was their main excursion into the economic field, and they settled it from every point of view except that of the economic future of the States whose destiny they were handling.

(12) Arthur James Grant & Harold Temperley, Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (1952)

Lloyd George had no thought of exacting impossible amounts of reparation from Germany. "Was it sensible," he said later, "to treat her as a cow from which to extract milk and beef at the same time?" But he was hampered by the ferocious demands of the British public, by the cries of "hanging the Kaiser" and "squeezing Germany till the pips squeak". At the most crucial moment of the peace negotiations Lloyd George was confronted by a telegram from 370 Members of Parliament demanding the he should make Germany pay. Of course he had to capitulate, and he replied that he would keep his pledge. What else could he do? If it was possible to produce an arrangement such people would accept, it was not likely to be a considered one or a wise one. It is probably true to say that, in so far as Lloyd George had a bad influence on the Treaty, it was because he faithfully reflected these forces.

If these were the difficulties created for Lloyd George at home, they were equally great abroad. He had to reconcile two colleagues, one of whom wanted a peace to be based almost wholly on force, and the other a peace based almost wholly on idealism. Lloyd George had to adjust the two points of view, and the task was inconceivably difficult. It meant self-effacement on his part, sacrifice of his pledges, of his consistency, sometimes even of his dignity. Yet he succeeded in many instances. There are points in which he is liable to severe criticism. But this fact should not exclude the services which his inconceivable adroitness and flexibility rendered to the common cause. It cannot be said that he neglected any purely British interests. The charge that will lie against him in history is that he neglected nobler and more universal interests.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)