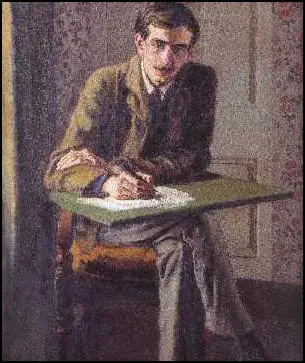

Duncan Grant

Duncan Grant, the only child of Major Bartle Grant and his wife, Ethel McNeil, was born in his family's ancestral home, The Doune, at Rothiemurchus, near Aviemore, on 21st January 1885. His early years were spent in India and Burma, where his father's regiment was stationed.

In 1893 he returned to England for his schooling. At Rugby he met Rupert Brooke and developed an interest in art. After leaving school he went to live with his uncle, Richard Strachey (1817–1908). This brought him into contact with his children, Lytton Strachey, James Strachey, Oliver Strachey and Philippa Strachey.

Grant studied at the Westminster School of Art. As his biographer, Quentin Bell, pointed out: "On coming of age Grant used a £100 legacy from another aunt, Lady Colvile, to study for one year (1906–7) in Paris, at Jacques-Emile Blanche's La Palette. While there he copied Chardin in the Louvre and ignored, or remained unaware of, the controversy caused by the Fauves. Thus, though an art student in Paris during one of the most revolutionary moments in the history of painting, he continued, for some years yet, to paint with sober colours and formal restraint."

On his return to London, Grant had a brief affair with his cousin Lytton Strachey, before starting a long-term relationship with John Maynard Keynes. In 1905 Virginia Woolf and several friends and relatives began meeting to discuss literary and artistic issues. The friends, who eventually became known as the Bloomsbury Group, included Grant, Strachey, Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Leonard Woolf, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell, Lytton Strachey, David Garnett, Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Virginia Woolf described him as being "a queer faun-like figure, hitching his clothes up, blinking his eyes, stumbling oddly over the long words in his sentences." He became a regular visitor to her Bloomsbury home. "How he lived I do not know. He was penniless. Uncle Trevor indeed said he was mad. He lived in a studio in Fitzroy Square with an old drunken charwoman called Filmer and a clergyman who frightened girls in the street by making faces at them. Duncan was on the best of terms with both. He was rigged out by his friends in clothes which seemed always to be falling to the floor. He borrowed old china from us to paint; and my father's old trousers to go to parties in.... He seemed to be vaguely tossing about in the breeze; but he always alighted exactly where he meant to."

Grant's cousin, Philippa Strachey, was secretary of the London Society for Women's Suffrage. She encouraged him to became interested in the subject of women's suffrage and in 1909 Grant entered the Artists' Suffrage League (ASL) in association with the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) poster competition. Grant submitted Handicapped! and shared the first prize of £5. The Common Cause newspaper described it as depicting "a stalwart Grace Darling type struggling in the trough of a heavy sea with only a pair of sculls, while a nonchalant young man in flannels glides gaily by, with a wind inflating his sail - the vote - treating with good temper a subject which often causes bitterness." (4th November, 1909)

In 1910 Grant's work was exhibited at the Grafton Galleries in London. This brought him to the attention of Edward Marsh, the wealthy art patron, who purchased his Parrot Tulips. Marsh later recalled that he decided to reject the advice of buying acknowledged masterpieces from the main Mayfair dealers. He said he found it much more exciting "to go to the studios and the little galleries, and purchase, wet from the brush, the possible masterpieces of the possible Masters of the future."

Grant helped Roger Fry, to select paintings for the exhibition entitled "British, French and Russian Artists" held at the Grafton Galleries, between October 1912 and January 1913. Artists included in the exhibition included Grant, Fry, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky.

Grant joined with Roger Fry and Vanessa Bell to form the Omega Workshops in 1913. According to his biographer, Quentin Bell: "While working closely together in the lead up towards the opening of the workshops, Grant and Bell moved into an intimate relationship which also marked the onset of an aesthetic partnership. Hitherto Grant's passions had been engaged almost always by members of his own sex and, although this essential aspect of his sexual nature never ceased to affect him, his union with Bell, and his friendship with her husband, played a determining role in the conduct of his life."

When the First World War was declared two pacifists, Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, formed the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." Grant joined the NCF. Other members included Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, C. E. M. Joad, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Wilfred Wellock, Herbert Morrison, Maude Royden, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Catherine Marshall, Alice Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Storm Jameson, Ada Salter, and Max Plowman.

Grant lived with Vanessa Bell and David Garnett at Wissett Lodge in Suffolk. Grant and Garnett worked on the farm as conscientious objectors but in 1916 a government committee on alternative service refused to let them continue there. They therefore moved to Charleston, near Firle, where they undertook farm work until the end of the war.

In 1918 Bell gave birth to Grant's child, Angelica Garnett. His biographer, Quentin Bell has argued: "Despite various homosexual allegiances in subsequent years, Grant's relationship with Vanessa Bell endured to the end; it became primarily a domestic and creative union, the two artists painting side by side, often in the same studio, admiring but also criticizing each other's efforts."

Dora Carrington was a regular visitor to Charleston. According to David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) she was shocked by the way they talked about Ottoline Morrell and Gilbert Cannan behind their backs. Carrington told Mark Gertler: "I think it's beastly of them to enjoy Ottoline's kindnesses and then laugh at her."

In 1935 Grant and Vanessa Bell accepted commissions to paint decorative panels for the new Cunard liner, RMS Queen Mary. However, unhappy with what he had produced, the work was rejected. They also provided the decorations in Berwick Church, that were completed in 1943.

During the Second World War he began an affair with the much younger Paul Roche. According to The Daily Telegraph: "One warm night in Piccadilly in 1946 Roche met the Bloomsbury post-impressionist painter Duncan Grant... Dressed up in a sailor suit as Roche was, Grant did not find out until years later about Roche's priestly secret.... Roche began to model for him on a regular basis and sometimes for Vanessa Bell." The relationship continued until Roche married and moved to the United States.

According to Margalit Fox: "Though observers over the years have described Mr. Roche and Mr. Grant as lovers, Ms. Roche de Aguiar said in a telephone interview that their relationship appeared to have been platonic. What is certain is that the two men shared a long, deep, loving friendship and that Mr. Grant was an early muse for Mr. Roche, encouraging him to write."

In the 1950s his reputation as an artist declined and he had difficulty selling his pictures except at very low prices. Frances Partridge pointed out: "Duncan Grant's charm was legendary. He never stopped painting, even during those years when his work was out of favour and his name unknown to the young; nor did it seem to affect him when fame returned to him. And he loved music. When he was well over eighty I invited him to the opera. Undeterred by having spent five mortal hours that day carefully studying an exhibition at the Tate, he arrived by Underground and on foot (not dreaming of taking a taxi), looking as usual remarkably like a tramp, with hair that seemed never to have known a brush, sat through the opera with unfaltering attention, and came back to supper afterwards with two much younger guests whom he easily outdid in animation."

Grant lived on his own at Charleston after the death of Vanessa Bell until the return of Paul Roche to England. In 1975 they took a house and spent six months in Tangier, where Paul nursed Grant through pneumonia.

Duncan Grant died bronchial pneumonia at the age of 93 at the home of Paul Roche in Aldermaston on 9th May 1978.

Primary Sources

(1) Frances Partridge, Memories (1981)

Duncan Grant's charm was legendary. He never stopped painting, even during those years when his work was out of favour and his name unknown to the young; nor did it seem to affect him when fame returned to him. And he loved music. When he was well over eighty I invited him to the opera. Undeterred by having spent five mortal hours that day carefully studying an exhibition at the Tate, he arrived by Underground and on foot (not dreaming of taking a taxi), looking as usual remarkably like a tramp, with hair that seemed never to have known a brush, sat through the opera with unfaltering attention, and came back to supper afterwards with two much younger guests whom he easily outdid in animation.

(2) Virginia Woolf, Old Bloomsbury (c. 1940)

Sometimes one began to meet a queer faun-like figure, hitching his clothes up, blinking his eyes, stumbling oddly over the long words in his sentences. A year or two before, Adrian and I had been standing in front of a certain gold and black picture in the Louvre when a voice said: "Are you Adrian Stephen? I'm Duncan Grant." Duncan now began to haunt the purlieus of Bloomsbury. How he lived I do not know. He was penniless. Uncle Trevor indeed said he was mad. He lived in a studio in Fitzroy Square with an old drunken charwoman called Filmer and a clergyman who frightened girls in the street by making faces at them. Duncan was on the best of terms with both. He was rigged out by his friends in clothes which seemed always to be falling to the floor. He borrowed old china from us to paint; and my father's old trousers to go to parties in. He broke the china and he ruined the trousers by jumping into the Cam to rescue a child who was swept into the river by the rope of Walter Lamb's barge, the 'Aholibah'. Our cook Sophie called him "that Mr Grant" and complained that he had been taking things again as if he were a rat in her larder. But she succumbed to his charm. He seemed to be vaguely tossing about in the breeze; but he always alighted exactly where he meant to.