Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Stephen, the daughter of Leslie Stephen and Julia Princep Duckworth, was born at Hyde Park Gate, Kensington, on 30th May 1879. Her mother had three children from her first marriage, George Duckworth (1868–1934), Stella Duckworth (1869–1897), and Gerald Duckworth (1870–1937). Over the next few years she gave birth to three more children: Thoby Stephen (1880), Virginia Stephen (1882) and Adrian Stephen (1883).

Vanessa's mother died on 5th May 1895, following an attack of influenza which had turned into rheumatic fever. The following year she began studying drawing at Arthur Cope's School of Art three times a week. She was especially close to her younger sister, Virginia Stephen.

Her biographer, Vanessa Curtis, has commented: "When Vanessa was not in her art class, the sisters often spent mornings companionably closeted away in a little class room off the back of the drawing-room, almost entirely made up of windows and perfect for quiet writing and painting."

In 1897, aged 18, her stepbrother George Duckworth, began taking her out. The author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) has pointed out: "She looked a vision of loveliness in her white dress and blue enamel brooch, yet underneath she resented the forced pomp of these occasions with some vigour, longing only for her paints and easel." Duckworth eventually turned his attentions to her sister Virginia, who later commented: "Vanessa might have been a famous beauty. I though far more intermittent, irregular and ill-kempt than she was, had more of the average of good looks."

Vanessa began attending the Slade School of Art in 1901. A fellow student, William Rothenstein, later recalled that she "looked as though she might have walked among the fair women of Burne-Jones's Golden Stair; but she spoke with the voice of Gauguin." Anne Olivier Bell has argued that "Vanessa Bell was a woman of grave and distinguished beauty, with a low and beautiful speaking voice - characteristics which tended to mask her wit and humour and capacity for laughter."

After the death of their father in 1904 Vanessa and Virginia moved to Bloomsbury. Their brother, Thoby Stephen, introduced them to some of his friends that he had met at the University of Cambridge. The group began meeting to discuss literary and artistic issues. The friends, who eventually became known as the Bloomsbury Group, included Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy, Arthur Waley and Duncan Grant.

Clive Bell fell in love with Vanessa. Virginia was at first unimpressed with Bell and compared him unfavourably with her father and brother. She wrote to her friend, Violet Dickinson: "When I think of father and Thoby and then see that funny little creature twitching his pink skin and jerking out his little spasm of laughter I wonder what odd freak there is in Vanessa's eyesight."

Vanessa at first rejected him but following the early death of Thoby Stephen, she married Bell on 7th February 1907. The couple had two sons - Julian Bell (1908-1937) and Quentin Bell (1910-1996). According to her biographer, Anne Olivier Bell: "Although Vanessa Bell shared her husband's interest in the developments of contemporary French art, her own painting remained essentially sober and tonal, having much in it of Whistler and of the New English Art Club, with which she sometimes exhibited."

Vanessa Curtis, the author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002), points out that after their marriage, Clive became very close to Virginia Stephen: "Virginia, envious of her sister's newfound married happiness, also began to court favour and affection from Clive. A flirtation between the two sprang up in Cornwall, when Vanessa was too wrapped up in her first baby, Julian, to pay much attention to anyone else. Clive, flattered, and feeling shut out by his wife, reciprocated with passion and longed to make the flirtation physical; Virginia, existing cerebrally and intellectually, was happier to draw the line at long, stimulating walks and clever letters."

In 1910 Clive Bell met Roger Fry in a railway carriage between Cambridge and London. His sister-in-law, Virginia Woolf, later recalled: "It must have been in 1910 I suppose that Clive one evening rushed upstairs in a state of the highest excitement. He had just had one of the most interesting conversations of his life. It was with Roger Fry. They had been discussing the theory of art for hours. He thought Roger Fry the most interesting person he had met since Cambridge days. So Roger appeared. He appeared, I seem to think, in a large ulster coat, every pocket of which was stuffed with a book, a paint box or something intriguing; special tips which he had bought from a little man in a back street; he had canvases under his arms; his hair flew; his eyes glowed."

Later that year Roger Fry, Clive Bell and Desmond MacCarthy went to Paris and after visiting "Parisian dealers and private collectors, arranging an assortment of paintings to exhibit at the Grafton Galleries" in Mayfair. This included a selection of paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, André Derain and Vincent Van Gogh. As the author of Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "Although some of these paintings were already twenty or even thirty years old - and four of the five major artists represented were dead - they were new to most Londoners."

The critic for The Pall Mall Gazette described the paintings as the "output of a lunatic asylum". Robert Ross of The Morning Post agreed claiming the "emotions of these painters... are of no interest except to the student of pathology and the specialist in abnormality". These comments were especially hurtful to Fry as his wife had recently been committed to an institution suffering from schizophrenia. Paul Nash recalled that he saw Claude Phillips, the art critic of The Daily Telegraph, on leaving the exhibition, "threw down his catalogue upon the threshold of the Grafton Galleries and stamped on it."

This exhibition had a marked impression on the work of Vanessa Bell. As Anne Olivier Bell pointed out: "Liberated from the English tradition of direct representation by the intoxicating example of the French and the stimulating theorizing of Bell and Fry, Vanessa's work grew increasingly bold, with a simplification of design and form and a free and joyous use of colour."

Clive Bell had a series of affairs, including an important long-term relationship with Mary Hutchinson, the wife of St John Hutchinson. In the spring of 1911 Vanessa went on holiday to Turkey with her husband and Roger Fry. During her stay Vanessa had a miscarriage and a mental breakdown. Virginia Woolf went out to help nurse her. She was also going through a period of depression. She wrote: "To be 29 and unmarried - to be a failure - childless - insane too, no writer." Both Vanessa and Virginia fell in love with Fry. That summer Vanessa began an affair with Fry. They tried to keep in secret from Virginia but on 18th January 1912, Vanessa wrote to Fry: "Virginia told me last night that she suspected me of having a liaison with you. She has been quick to suspect it, hasn't she?" Knowledge of the affair was a major influence on why Virginia decided to marry Leonard Woolf.

Roger Fry selected paintings for the exhibition entitled "British, French and Russian Artists" that was held at the Grafton Galleries, between October 1912 and January 1913. Fry used four of Vanessa Bell's paintings in the exhibition. Other artists in the show included Duncan Grant, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky. According to David Boyd Haycock: "Fry's second exhibition was not as badly received as the first. The intervening two years had seen a number of avant-garde shows in London, highlighting the work of continental modernism, and the art world was suddenly awash with isms."

In 1913 Vanessa Bell joined with Roger Fry and Duncan Grant to form the Omega Workshops in 1913. Other artists involved included Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Percy Wyndham Lewis and Frederick Etchells. Fry's biographer, Anne-Pascale Bruneau has argued that: "It was an ideal platform for experimentation in abstract design, and for cross-fertilization between fine and applied arts.... However, in spite of a number of commissions for interior design, the company survived the war years with difficulty, and closed in 1919."

When the First World War was declared Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, formed the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." Vanessa and her husband, who were both pacifists, joined the NCF. Clive Bell's pamphlet Peace at Once (1915), in which he courageously argued for a negotiated settlement with Germany, was seized by the police and was destroyed.

Vanessa Bell lived with Duncan Grant and David Garnett, first at Wissett Lodge in Suffolk, then at Charleston Farmhouse, near Firle, where he undertook farm work until the end of the war. In 1918 Bell gave birth to Grant's child, Angelica Garnett. His biographer, Quentin Bell has argued: "Despite various homosexual allegiances in subsequent years, Grant's relationship with Vanessa Bell endured to the end; it became primarily a domestic and creative union, the two artists painting side by side, often in the same studio, admiring but also criticizing each other's efforts."

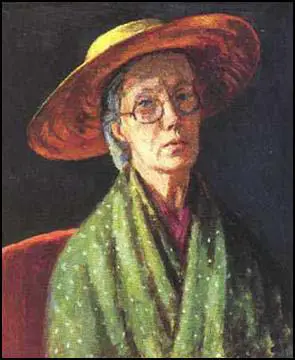

Vanessa Curtis, the author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) has pointed out: "Duncan Grant, had reverted back to homosexuality after fathering her daughter, Angelica. Vanessa was becoming an expert at hiding her disappointment, so instead she took pleasure in painting companionably by Duncan's side." Her first exhibition took place at the Independent Gallery in London in 1922, and in the years that followed she had solo shows at the Cooling, Lefevre, Leicester, and Adams galleries. Anne Olivier Bell has argued: "She turned to the form of representational art which she felt best suited her. Her method, which allowed her to explore and to celebrate the solidity and brilliance of the natural world, was not radically changed for the rest of her life. Although she had a considerable gift for portraiture and used her friends and family as subjects when she could prevail upon them to sit, she painted few formal portraits and, from necessity as much as choice, applied herself to still life, landscape, interiors with figures, and, from time to time, interpretations of the work of the Old Masters."

Her son, Julian Bell, shared her anti-war sentiments and wrote an introduction to the anti-war book, We Did Not Fight: 1914-18 (1935). The book included contributions from Siegfried Sassoon, Richard Sheppard, Bertrand Russell, Norman Angell, Harry Pollitt and James Maxton. In an article in the Times Literary Supplement he explained his political views: "Like nearly all the intellectuals of this generation, we are fundamentally political in thought and action: this more than anything else marks the difference between us and our elders. Being socialist for us means being rationalist, common-sense, empirical; means a very firm extrovert, practical, commonplace sense of exterior reality."

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Julian Bell decided that he must contribute to the war against fascism. Vanessa tried to persuade him not to go. So did his friends. David Garnett later recalled how he went to Charleston "to try to persuade him that he would be far better employed in helping to prepare for inevitable war against Hitler than in risking his life in Spain where he could take no effective or important part." Virginia Woolf arranged for Bell to meet Kingsley Martin and Stephen Spender, as they both had unpleasant experiences in Spain during the early stages of the war.

E. M. Forster also tried to convince him that it would be an immoral act to take part in a war. Bell defended his decision by claiming that he was no longer a pacifist. However, after pleading from his mother, he agreed that he would go to Spain, not as a soldier in the International Brigades but as an ambulance driver with the British Medical Aid Unit.

Julian Bell worked with, Dr. Archie Cochrane, an old friend from King's College. His fellow ambulance driver, Richard Rees, claimed that Bell "was having the most wonderful time of his life". He appeared to find the danger of his actions exciting. When his ambulance was destroyed by a bomb on 15th July, he volunteered to go to the front as a stretcher-bearer.

On the 18th July, 1937, the British Medical Unit received a replacement vehicle for Bell. Later that day he was driving his ambulance along the road outside Villanueva de la Cañada when it was hit by a bomb dropped by a Nationalist pilot. Bell was taken to the military hospital at El Escorial near Madrid. Dr. Archie Cochrane was the doctor who treated him in the receiving-room. As soon as he examined him, he realized that he had been mortally wounded; a shell fragment had penetrated deep in his chest. Bell was still conscious and murmured to Cochrane: "Well, I always wanted a mistress and a chance to go to war, and now I've had both." He then fell into a coma from which he never awakened.

Vanessa Bell spent the first week of her grieving in bed at the studio in Fitzroy Street, unable to be moved back to Charleston Farmhouse. Eventually she was brought back to Firle and during this period she was looked after by Virginia Woolf.

Eventually, Vanessa returned to painting. Her daughter, Angelica Garnett, commented: "She presided, wise yet diffident, affectionate and a little remote, full of unquestionable spirit. Her feelings were strong, and words seemed to her inadequate. She was content to leave them to her sister and to continue painting."

On 28th March, 1941, Virginia Woolf wrote a letter to Leonard Woolf: "I feel certain that I am going mad again. I feel we can't go through another of those terrible times. And I shan't recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can't concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don't think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can't fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can't even write this properly. I can't read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that - everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can't go on spoiling your life any longer." A second letter was addressed to Vanessa. It concluded, "if I could I would tell you what you and the children have meant to me. I think you know." Later that morning she committed suicide by drowning herself in the Ouse, near her home in Rodmell.

Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant accepted commissions to paint decorative panels for the new Cunard liner, RMS Queen Mary. However, unhappy with what he had produced, the work was rejected. They also provided the decorations in Berwick Church, that were completed in 1943.

Vanessa Curtis has argued that after the death of Virginia Woolf: "Vanessa withdrew further into painting and lived the next twenty years of her life in relative isolation, relying only on the company of Duncan, her children and grandchildren, and the calming routine of putting paintbrush to canvas... Other than the company of friends, one of the great pleasures that old age brought to Vanessa was a clutch of grandchildren. Angelica had married David Garnett and produced four daughters; Quentin had married Anne Olivier Popham and had two daughters and a son. The children knew Vanessa as a doting grandmother, and Duncan and Clive as two amusing grandfathers who would allow them to experiment with paints and brushes in the airy studio."

Vanessa Bell died at Charleston Farmhouse, at the age of eighty-one after a bout of bronchitis, on 7th April 1961. She was buried on 12th April, without any form of service, in Firle Parish Churchyard.

Primary Sources

(1) Vanessa Curtis, Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

George Duckworth, who had an independent income, a job as private secretary to Austin Chamberlain, and a string of invitations to balls and parties, decided that his reputation would be improved further still if he were to attend such events with a beautiful, motherless half-sister on his arm. In 1897, he started to introduce Vanessa, aged eighteen years old, into society, but without much success, for, as Virginia had known for years, "what was inside Vanessa did not altogether correspond with what was outside".

Vanessa had certainly inherited the legendary Pattle beauty from Julia and Stella, but it had manifested itself in a less ethereal, more statuesque way. She looked a vision of loveliness in her white dress and blue enamel brooch, yet underneath she resented the forced pomp of these occasions with some vigour, longing only for her paints and easel. Virginia, too, was attracting admiring glances wherever she went, a fact that she acknowledged with easy vanity: "Vanessa might have been a famous beauty. I, though far more intermittent, irregular and ill-kempt than she was, had more of the average of good looks."

After a year or so of dragging Vanessa to these events, George gave up on her and started to try and persuade Virginia to attend in her place, putting incredible pressure on the nervous, unwilling teenager by telling her that unless she accompanied him he would be forced to hire a "whore" for the evening. Virginia attended several events with little more success than her sister had - remembering that Vanessa had been frustratingly silent at the dinner table, she endeavoured to earn George's praise by waxing lyrical on a good many subjects, mostly unprompted. The society ladies tittered and George was furious. He scolded her all the way home, bemoaning his bad luck at having such a badly brought-up girl for a sister.

To make matters worse, he had started to creep into her bedroom late at night, flinging himself upon the bed and proclaiming love. This he did to Vanessa as well, but whether his treatment of the Stephen girls could be described as abuse is a controversial matter, which still encourages considerable debate even today. It is certainly true that in later years when the girls wrote to George, they still used terms of great affection, and they even went on holiday with both Duckworth brothers; unlikely behaviour from the victims of any serious sexual abuse. There is no doubt, though, that at the time, this intimidating and suffocating conduct caused distress to the highly private Stephen girls, both of them reserved in their affections and taught to repress emotion in front of their father, and mourning the mother and half-sister who might, had they lived, have afforded them some protection.

(2) Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf (1996)

Vanessa was establishing herself as a professional painter (showing at the Omega and the New Movement in Art shows in 1917, painting a big Matisse-like naked figure in The Tub). She was settling into her ramshackle, isolated, intensely domestic life at Charleston, where she set up a small school in 1917, and where her boys were getting bigger and rowdier. She was involved in a tense triangular relationship with Duncan and his lover, and was still being brooded over by a jealous Roger Fry. Duncan's daughter Angelica was born on Christmas Day 1918 (her future husband, her father's lover David Garnett, was there at her birth). At once there was a crisis; the baby nearly died, badly handled by the local doctor.

(3) Peter Stansky & William Abrahams, Journey to the Frontier (1966)

Mrs Woolf was told by Vanessa that the crucial factor in bringing Julian round to a compromise had been some letters he was shown describing the plight of a young English Communist in the International Brigade. The young man in question, who had gone out impulsively to Spain, was appalled by the horrors of the battlefield, and disillusioned by the strict military discipline that was imposed by the Communist leadership of the Brigade. It seems highly unlikely that Julian was influenced in any significant degree by this correspondence, no matter what his mother chose to believe. His own decision to go out to Spain was in no sense unpremeditated; he took a hard-headed view of death and suffering as the necessary evils of war; as an admirer of the "military virtues", and as a serious student of military affairs, he would entertain no idealistic notion of a peoples' army free of rank and discipline. One can only conclude that, as a kindness to his mother, he allowed her to think that he was making this compromise not simply as a concession to her fears for his safety, but for other reasons as well.

Why had the discussions with his mother, to whom he would listen with more respect and love than to any other person, led only to this compromise which fell far short of satisfying her wishes? (True, he was not to bear arms, but he was still going to Spain, he would be on the battlefields, he would be exposed to danger.) Chiefly, it would appear, because he had made a commitment to himself to go, which he refused to break. It was his obligation and test, he felt, to prove himself to himself, as a significant member of his generation who could make a contribution of example, experience and knowledge, rather than languish in a backwater, whether in London or China, as a mere second-generation and second-rate Bloomsburian.

His determination seemed to Mrs Woolf evidence of how he had changed, but determination was not really a new aspect of Julian's character. It was simply that now, for the first time, with absolute seriousness, he had fixed on something to be determined about.

(4) Julian Bell, letter to Vanessa Bell (1st July, 1937)

I do think I'm being of real use as a driver, in that I'm careful and responsible and work on my car - a Chevrolet ambulance.. Most of our drivers are wreckers, neglect all sorts of precautions like oiling and greasing, over speed etc. Any really good and careful drivers out here would be really valuable.

The other odd element is the Charlestonian one of improvising materials - a bit of carpet to mend a stretcher, e.g. - in which I find myself at home.

(5) Vanessa Curtis, Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

Vanessa was robust, earthy and Madonna - like in her appearance. Around her, chaos reigned supreme at Charleston, but she remained the resolute, matriarchal anchor in the centre, soothing, calming and organizing. She was resolutely practical, having inherited this trait from Julia, and took naturally to ordering servants around (although she was not above doing her own cooking, and often would make scones in the kitchen). She was ruthless when it came to employing the right sort of help at Charleston, hiring and firing a number of 'helps' in quick succession, finally settling upon Grace Higgens, a cook who helped look after the children and who eventually stayed for forty years. It was a sign of Vanessa's calmness and capability in her home environment that Grace could never find a disloyal word to say about her or any of her "Bloomsbury" friends. Virginia, in contrast, was never to master the employer/servant relationship properly. Her two hired helps, Nellie and Lottie, drove her to distraction, and vice versa, over a period of eighteen years. They constantly caused conflict, resigned and then came crawling back; Virginia was not assertive enough to refuse them and so the pair would move back in, only for the trouble to start up all over again.

Vanessa was often to be found sitting at her easel in the attic studio at Charleston, or in the garden room, sewing or sleeping while the men entered into animated discussion. She was serene and measured, earthy yet controlled, likened by Virginia to a bowl of golden water that bubbled up to the brim but never overflowed. In contrast, Virginia was edgy, nervous and often hyperactive. All her life she was prone to fits of excitement or temper, both of which set alarm bells ringing in Leonard, for they often indicated the beginning of a bout of debilitating illness. She was ungainly when she walked; tall and thin, awkward, ill at ease in her own body, unsure of her femininity, insecure and reluctant to look in the mirror. Even so, her many friends and admirers were transfixed by her face as it changed and grew expressive in conversation.

Her looks were more unconventional than Vanessa's; delicate, transitory, ethereal; changing, in her forties and fifties, into a very fragile, haunted beauty. Although in her youth she had not resembled Julia as much as Stella or Vanessa did, something of Julia Stephen's weary severity crept into Virginia's face as she grew older.

Virginia was unhappy with her body image and weight for most of her life, finding it difficult to eat and going for long periods without doing so. Vanessa, on the other hand, although a frugal eater who disliked foreign food, started each day with a breakfast of toast and salt, dined off roast meats in the evening and was generally well nourished both by the produce from the Charleston farm and by her capable cook, Grace, who transformed it into delicious meals.

Vanessa had not had the three children to look after, she might have achieved considerably more fame as a painter. Yet she had domestic help with the children, enough money to live comfortably, and a few hours per day to concentrate on her art, which, on the infrequent occasions that she exhibited, sold well and was admired by other artists. Vanessa was innovative, inspiring several designs for Roger Fry's Omega Workshops and showing her paintings at both his Post-Impressionist Exhibitions. In return, he reviewed her work favourably for Vogue magazine in 1926, declaring that she must take her place with the leading British painters of the day. Virginia remained envious of Vanessa's family and the hectic, affectionate atmosphere at Charleston, although her pain was alleviated by realizing that she was becoming financially successful through her writing (To the Lighthouse financed several improvements to Monk's House).

The sisters found the expression of emotions to anyone other than each other, difficult. Vanessa's calm exterior hid a passionate nature, and as a wife she was demanding and needy, marrying Clive in the

confident hope of sustaining a full, satisfying sexual union. Although the marriage produced two children and enabled Vanessa to boast to Virginia about her sexual expertise (in comparison to Virginia's apparent frigidity), the physical side was short-lived, resulting in her damaging affairs with Roger Fry and Duncan Grant. Again, after the initial passion had worn off between Vanessa and Duncan, that relationship settled into the familiar pattern of Vanessa providing comfort and acting as confidante to Duncan, who brought a string of male lovers back to Charleston for her to look after. The effect on this passionate but emotionally repressed woman must have been devastating, but once again Vanessa kept her true feelings tucked away, concentrating instead upon her artistic talent and the demands of motherhood. Although Vanessa and Duncan were to remain together for more than forty years after Angelica's birth, Vanessa rarely had sexual relations again during that period.

Virginia's sexuality was far more complex, but unlike Vanessa, she had the constant and total support of a husband who was rarely absent from her side. Although after her honeymoon it seems as if the marriage became platonic very quickly (even during the honeymoon Virginia had written to her friend Ka Cox, enquiring in a puzzled way as to why people made such a fuss about copulation), there was instead a bottomless supply of affection, loyalty and intimacy to be drawn upon. Leonard was forced to do exactly what Vanessa Bell had done - he buried his physical desires deep down inside and substituted other pleasures instead: writing, publishing, gardening and pets. Virginia was not to be pressured or worried in any way, so a companionable routine of walks, talks and writing became the preferred existence for them both.

(6) Vanessa Curtis, Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

Vanessa was not as devastated after Virginia's death as those close to her thought that she would be. Fearing a similar collapse to the one that had followed Julian's death, the family clustered around her anxiously in the days following the discovery of Virginia's body. Instead, Vanessa withdrew further into painting and lived the next twenty years of her life in relative isolation, relying only on the company of Duncan, her children and grandchildren, and the calming routine of putting paintbrush to canvas. She continued to maintain an affectionate relationship with her brother-in-law, Leonard Woolf, up until her death, corresponding with him on the subject of Virginia's letters (which he was considering publishing) with some apprehension...

Other than the company of friends, one of the great pleasures that old age brought to Vanessa was a clutch of grandchildren. Angelica had married David Garnett and produced four daughters; Quentin had married Anne Olivier Popham and had two daughters and a son. The children knew Vanessa as a doting grandmother, and Duncan and Clive as two amusing grandfathers who would allow them to experiment with paints and brushes in the airy studio.