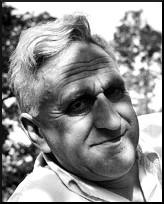

Kingsley Martin

Kingsley Martin, the second of four children of Basil Martin and Margaret Turberville, was born in Ingestre Street, Hereford, on 28 July 1897. Kingsley father had initially been a Congregational minister but later he became a Unitarian. The Rev. Martin was a pacifist and in 1899 campaigned against the Boer War. He was also a socialist and a active member of the Labour Party.

Martin later wrote: "I was proud of holding my father's opinions. I was a pacifist and socialist among conservatives without knowing what these labels meant. This was bad for me. All boys in adolescence must break with their parents. My trouble was that my father gave me no chance at all to quarrel with him. If he had been a dogmatic Christian, I should have reached my later humanism long before I did. If he had been an atheist I might have relapsed into some form of Christian faith. But he was ready to discuss everything and to yield when he was wrong. I could not quarrel. On the contrary, I fought side by side with him, and was a dissenter, not against his dissent, but with him against the Establishment. His causes became my causes, his revolt was mine."

Martin's biographer, Adrian Smith, has argued: "His father was known locally as a man of the highest integrity who stuck fast to his Christian socialist principles, not least his belief in absolute pacifism. He attracted grudging respect but often harsh criticism, not just from the respectable burghers of Hereford but also from the elders in his own church. His was a stormy and demanding ministry, borne with good grace and fortitude, and setting an example the adult Kingsley endeavoured to match, albeit with only partial success."

1902 Education Act

Basil Martin was also involved in the campaign against the 1902 Education Act introduced by Arthur Balfour. The previous Education Act had been popular with radicals as school boards were elected by ratepayers in each district. This enabled nonconformists and socialists to obtain control over local schools. The Balfour legislation abolished all 2,568 school boards and handed over their duties to local borough or county councils. These new Local Education Authorities (LEAs) were given powers to establish new secondary and technical schools as well as developing the existing system of elementary schools.

Nonconformists and supporters of the Liberal and Labour parties campaigned against this legislation. John Clifford formed the National Passive Resistance Committee and by 1906 over 170 men had gone to prison for refusing to pay their school taxes. This included 60 Primitive Methodists, 48 Baptists, 40 Congregationalists and 15 Wesleyan Methodists.

Martin later explained in Father Figures (1966): "My father was involved in the passive resisters' fight against Balfour's Education Act of 1902. Each year father and the other resisters all over the country refused to pay their rates for the upkeep of Church Schools. The passive resistors thought the issue of principle paramount and annually surrendered their goods instead of paying their rates. I well remember how each year one or two of our chairs and a silver teapot and jug were put out on the hall table for the local officers to take away. They were auctioned in the Market Place and brought back to us. Mother and I were taken for our first motor ride to one of these village auctions where father would explain the nature of passive resistance before the sale began. We drove to a village some fifteen miles away, sometimes travelling at the frightening speed of twenty miles an hour. In those days roads were deep in dust, and you could tell if a car had passed because the hedges were white. I remember three small boys running behind each other pretending to be a motor. The first said he was the driver, the second a car, and the third the smell."

Kingsley Martin and the First World War

Kingsley won a scholarship to Mill Hill, a nonconformist public school. He was still at school when he was called up to the British Army in 1916. As a pacifist he was totally opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. A conscientious objector, he refused to serve in the armed forces but was willing to carry out non-military duties. After a few months working as a medical orderly in a British hospital treating wounded soldiers, Martin joined the Society of Friends' Ambulance Unit (FAU) and later that year was working on the Western Front.

He later wrote: "In my ward, there were twenty-five men who were literally half dead. They were very much alive in their top halves, but dead below the waist. The connection between their brain and their natural functions were broken. They could feel nothing in their hips or legs, and in spite of being constantly rubbed with methylated spirit, they had bedsores you could put your hands in."

Fabian Society

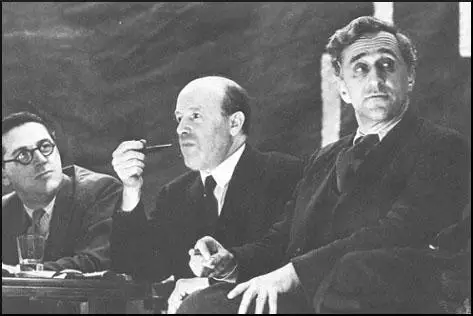

In 1919 Martin took up his place at Magdalene College that he had won at Cambridge before the war. While studying at university he joined the Union of Democratic Control and the Fabian Society where he met George Bernard Shaw, Graham Wallas, John Maynard Keynes, Douglas Cole and Sidney Webb and Harold Laski. Beatrice Webb wrote in her diary: "Kingsley Martin was unkempt and with the appearance of being unwashed, with jerky, ugly manners, but tall and dark - with a certain picturesque impressiveness of the Maxton type. He is a fluent and striking conversationalist - intellectually ambitious - with a certain religious fervour for social reconstruction. One of the promising younger members of the Fabian Society."

After obtaining a first-class degree at Cambridge University, Martin taught at Princeton University (1922-23) in the United States. When Martin returned to England, Maynard Keynes employed him as a book reviewer for his journal, The Nation. Keynes also persuaded William Beveridge, to give Martin a teaching post at the London School of Economics (1924-27). During this period he published The Triumph of Lord Palmerston (1924) and French Liberal Thought in the Eighteenth Century (1929).

At first Kingsley Martin enjoyed life as an academic: "The London School of Economics... was then, as it always has been, a wonderful home of free discussion, happily mixed race, and genuine learning. It seemed my natural home. My socialist views were vague, but not my sympathies. Like my friend Harold Laski, I believed passionately that capitalism was evil and doomed, and that it was useless to talk of liberty unless it was based on a large measure of social equality. I came into contact with most of England's leading Socialists, who completed my conversion."

However, Martin clashed with William Beveridge, the director of the LSE but fell in love with Eileen Power: "I never hit it off with Beveridge, though I recognised from the beginning that he was a man of extraordinary ability. I once, and only once, pleased Beveridge. I said that he 'ruled over an empire on which the concrete never set'. He was so delighted with this remark that he constantly quoted it, always attributing it, however, to Eileen Power, with whom, like everyone else, I assume was more or less in love. Eileen, indeed, was one of the most attractive women I have ever known. She was good-looking, and carried her erudition as a medieval scholar with wit and grace. She wrote delightfully, her account of the domestic life of nunneries would never bore anyone, and her Medieval People showed that careful scholarship can be made popular and achieve large sales."

Kingsley Martin and the Manchester Guardian

Harold Laski suggested to C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, that Martin would make a good replacement for C. E. Montague, the chief leader writer, who wanted to retire and write novels. He later wrote: "C. P. Scott wrote he had long been looking for a leader writer and would I take C. E. Montague's place on the Manchester Guardian at a salary commencing at £1,000 a year. This was an extraordinary offer from C. P. Scott, who usually thought anyone should pay for the privilege of writing for the Manchester Guardian." In the autumn of 1927 Martin accepted Scott's offer of £1,000 a year and ended his career as an academic.

Adrian Smith has pointed out: "Writing leaders for the legendary editor–proprietor C. P. Scott would have seemed the ideal appointment for someone so firmly rooted in the nonconformist tradition, but again Martin found himself at odds with his superior. He quickly encountered difficulties in reconciling an unbridled faith in democratic socialism with the Scott family's enthusiasm for the Liberal revivalism of a rejuvenated Lloyd George. Leaders were regularly rewritten in more temperate language, or simply spiked, and after three turbulent years in Manchester Martin learned that his contract would not be renewed. At the end of a decade of sharply contrasting fortunes he returned to London in 1930 desperate to revive a flagging career."

The New Statesman

Martin left the Manchester Guardian in 1930. Soon afterwards, Arnold Bennett, one of the directors of the New Statesman, asked him to become editor of the journal. Under Martin's guidance the journal became Britain's leading political weekly. He admitted in his autobiography: "In general we supported the Left Wing of Labour. Our independence was infuriating to the leaders of the party. Politicians think in terms of votes, and do not understand that in the long run it is the climate of opinion that matters."

Adrian Smith points out: "Kingsley Martin set out to make the New Statesman and Nation the flagship weekly of the left, articulating a brand of democratic socialism compatible with mainstream Labour thinking, while at the same time reserving the right to question and provoke. Thus, the paper remained loyal to Labour, but at the same time constituted a valuable forum for dissent. Indeed Martin positively relished being a perpetual critic of the Labour leadership, in or out of office. This refusal to follow a narrow party line was in many respects the key to the New Statesman's success, witness its close association from the mid-fifties with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, of which Martin was a founding father."

Kingsley Martin later recalled: " I combined in myself many of the inconsistencies and conflicts of the period which long tried to reconcile pacifism with collective security, and a defence of individual liberty with the necessity of working with Communists against Fascists. I suppose my prime attitude was a dissenter's. A dissenter sees the world is bad and expresses his moral indignation.... I tended to be angry. War was always the ultimate horror, and I could not bear to be silent about the sufferings of minorities and cruelty inflicted on individuals, even when the aggressors were my friends. At times the paper became more than anything else the voice of the minorities and a vehicle of protest. It also had a constructive, Socialist side."

The author of New Statesman: Portrait of a Political Weekly (1996) has pointed out: "When, with reluctance, he (Kingsley Martin) handed over the editorial reins in December 1960, the paper's weekly sales had increased sixfold to 80,000, the circulation in January 1931 having stood at a mere 14,000. Advertising revenue in 1960 had grown to a remarkable £100,000 per year, ensuring a healthy return for those directors who a generation earlier had gambled on an unproven young journalist turning their paper round. As chairman until his death in 1946, Keynes applauded evidence of commercial enterprise while sensibly bowing to editorial integrity in matters of potential conflict. The Keynes–Martin partnership was not always harmonious, but it proved remarkably productive."

Death of Kingsley Martin

After leaving the New Statesman Kingsley Martin produced two autobiographical works, Father Figures (1966) and Editor (1968). A keen chess player, he also rediscovered a passion for oil painting. He also spent a great deal of time travelling and suffered a stroke while in Egypt. He was rushed to the Anglo-American Hospital in Cairo, where he died of a heart attack on 16th February 1969. He donated his body for medical research.

Primary Sources

(1) In his book, Father Figures, Kingsley Martin explained the influence that his father had on his political and religious opinions.

I was proud of holding my father's opinions. I was a pacifist and socialist among conservatives without knowing what these labels meant. This was bad for me. All boys in adolescence must break with their parents. My trouble was that my father gave me no chance at all to quarrel with him. If he had been a dogmatic Christian, I should have reached my later humanism long before I did. If he had been an atheist I might have relapsed into some form of Christian faith. But he was ready to discuss everything and to yield when he was wrong. I could not quarrel. On the contrary, I fought side by side with him, and was a dissenter, not against his dissent, but with him against the Establishment. His causes became my causes, his revolt was mine.

(2) Kingsley Martin, Father Figures (1966)

My father was involved in the passive resisters' fight against Balfour's Education Act of 1902. Each year father and the other resisters all over the country refused to pay their rates for the upkeep of Church Schools. The passive resistors thought the issue of principle paramount and annually surrendered their goods instead of paying their rates. I well remember how each year one or two of our chairs and a silver teapot and jug were put out on the hall table for the local officers to take away. They were auctioned in the Market Place and brought back to us.

Mother and I were taken for our first motor ride to one of these village auctions where father would explain the nature of passive resistance before the sale began. We drove to a village some fifteen miles away, sometimes travelling at the frightening speed of twenty miles an hour. In those days roads were deep in dust, and you could tell if a car had passed because the hedges were white. I remember three small boys running behind each other pretending to be a motor. The first said he was the driver, the second a car, and the third the smell.

(3) Kingsley Martin and his school friend, Tom Applebee, both refused to join the British Army when called-up in 1916.

We agreed it was no good calling yourself a Christian, promising to return good for evil and love your enemies, if you took part in a vast horror of lies, hatred, and slaughter.

I appeared before a tribunal while I was still at school. This had an unpleasant side. I was turned out of the study which I shared with other prefects, and the boys would hit me on one cheek and ask whether I would offer the other. This mild persecution rather flattered my vanity.

I wrote a defence in the school magazine, which was refused because it was thought to reflect badly on the school's reputation. It was passed round, and some of the older boys read it and treated me with a kind of deference. One simple-minded athlete looked at me with genuine contempt.

Since then I have often asked myself whether he was right, whether the men who became C.Os. were really those who were, consciously or subconsciously, more afraid of a bayonet in their guts than other people. Analysis might show that C.Os. had more than the usual repulsion from pain and death. But the matter was more complicated than that. The demand for courage came in France, not in England, where the herd, and particularly one's womanfolk, usually made it difficult to refuse a uniform.

For my part, my predominant fear was that I might miss the war. No doubt I was glad that I was less likely to be killed than other people, but though I was in many ways a coward I have no memory of being frightened of death. Physical courage scarcely enters the question when one is eighteen.

(4) In 1916 Kingsley Martin worked as a medical orderly in a hospital treating wounded British soldiers.

In my ward, there were twenty-five men who were literally half dead. They were very much alive in their top halves, but dead below the waist. The connection between their brain and their natural functions were broken. They could feel nothing in their hips or legs, and in spite of being constantly rubbed with methylated spirit, they had bedsores you could put your hands in.

(5) When Kingsley Martin arrived in France in 1916 he worked at the Society of Friends Ambulance Train in Rouen.

I tracked down my ambulance train at Sootteville railway siding, not far from Rouen. It was an ancient train, with modern coaches only in the centre, and coaches and fourgons without corridors at both ends.

Two of us worked in the ward, a couple of doctors and two or three nurses lived in the central coaches. Each coach was arranged to take twenty lying patients, with floor-space on which to dump five more on stretchers if necessary. Alternatively, forty or fifty men would sit in the coach if they were walking cases.

There were two pails for soup or cocoa or tea, a brass urn for drinking water. A primus stove was the most important object; a good deal of life turned on the question of whether one could get enough paraffin by fair means or foul. Another major objective was to get as many decent blankets as possible. If you could steal a soft khaki blanket of the type used for officers you were proud of yourself. At each hospital base you swiftly and surreptitiously swapped new blankets for the bloodstained and muddy ones that came into the ward.

(6) The Ambulance Train would travel to the Western Front where it would collect the wounded and take them back to Rouen.

The front was comparatively quiet when I first joined the train. The Battle of the Somme was over, and we travelled up that stricken valley without incident. Everywhere shell-holes, barbed wire and stumps of trees. Places like Ypres, and many villages whose names we saw on the railwayside, had disappeared. Arras had a line of latticed ruins, and a church which looked as if it was still a place for visitors - until one got closer and found it was a shell.

We would load at a casualty clearing station behind the lines, and travel down very slowly indeed to Rouen or Etaples. Perhaps it would be four in the morning when we loaded. We would reach our base at seven at night, unload, sweep out, clear up, and would be preparing for some sleep about ten, when a message would come that we were evacuating a load of Blighty convalescents from Boulogne at five a.m. Then we got out our disgusting groundsheets again, lowered the beds for the sitting cases and dozed until the load arrived of cheerful patients bound for England, with arms in slings, legs in bandages, or head-wounds that weren't too serious. We would take them to Boulogne, unload them, scrub out the ward, shake out the blankets, ready for another slow progress to the back of the front.

(7) In his autobiography, Father Figures, Kingsley Martin wrote about how soldiers reacted when they had been wounded.

I recall the wounded as being incredibly patient and unhappy. The one thing they asked, hopefully, prayerfully, was whether they'd caught a "Blighty" this time. Was their wound bad enough to get them home? Did I think it might get them out of the war altogether? That was perhaps too much to hope for. After all, they were damned lucky to be wounded. Most of their company or battalion would never come home.

A common dodge was to shoot your foot through a sandbag so that the powder did not show. A guard was put to watch anyone who damaged himself. What I recall most from that time is the total loss of belief that the war had any object; it was just an incredible calamity that had to be endured. They were men without faith or hope. They were bitterly critical about people at home. They never grudged your comparatively cushy job. They would give you a dig in the ribs, "Oh, you're a Quaker, are you? Good luck to you. I wish I'd thought of that dodge myself." You'd been smarter than they had. A disconcerting view as long as you remained any kind of idealist.

(8) In 1918 Kingsley Martin had to treat soldiers that had been attacked by German mustard gas.

It was our first experience of mustard gas. The men we took were covered in blisters. The size of your palm most of them. In any tender, warm place, under the arms, between the legs, and over the face and neck. All their eyes were streaming, and hurting in a way that sin never hurts.

(9) In his book, Father Figures, Kingsley Martin described the German attempt to breakthrough at the Western Front in March 1918.

Suddenly, as we were arranging our game of football, someone noticed that an engine was arriving for our train. We bundled in, and up to the casualty clearing station. Something new. The Germans had broken through. No one who did not know the stability of trench war can realise the astonishment of the German push. Thousands and hundreds of thousands of men had died pushing the line forward a hundred yards; that had been the rule for the past two years. And here was a push of thirty miles and an army crumpled up in a day or two. French soldiers shouted at us, "What's happened to the bloody Fifth Army?" The British had lost the war. It was said not to be safe to go out because the French were so angry.

Up at the line again we became aware in the early morning mist - I remember it vividly today - of thousands of bodies, acres and acres of them, lying out on the ground, with scraps of German grey or British khaki hanging out over the stretchers. They were very few bearers, and so we loaded the train ourselves, making no distinction between England and Germans; every inch of the train was full.

(10) Kingsley Martin argued that the British Army was close to mutiny when the American army arrived at the Western Front.

The British army, like the French, might have followed the Russians and mutinied in 1917-18. The arrival of the American army - brash, unpopular as it was - meant a change in mood. The Allied counter-offensive seemed astonishingly well organised and tidy.

Delays in demobilisation and lack of jobs brought disillusion. Before long the men were singing 'Homes for Heroes' and cursing Lloyd George. The Canadians and the Australians fought in their camps. The only time in my life when revolution in Britain seemed likely was in 1919.

(11) In 1921 Kingsley Martin, Eileen Power and Barbara Wootton were invited to spend a weekend with Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb. Afterwards Beatrice wrote about the weekend in her diary.

Kingsley Martin was unkempt and with the appearance of being unwashed, with jerky, ugly manners, but tall and dark - with a certain picturesque impressiveness of the Maxton type. He is a fluent and striking conversationalist - intellectually ambitious - with a certain religious fervour for social reconstruction. One of the promising younger members of the Fabian Society.

(12) Kingsley Martin, Father Figures (1966)

In the autumn of 1924 I started work at the London School of Economics. It was then, as it always has been, a wonderful home of free discussion, happily mixed race, and genuine learning. It seemed my natural home. My socialist views were vague, but not my sympathies. Like my friend Harold Laski, I believed passionately that capitalism was evil and doomed, and that it was useless to talk of liberty unless it was based on a large measure of social equality. I came into contact with most of England's leading Socialists, who completed my conversion.

Sir William Beveridge was director when I joined the staff in 1924. He accepted me first on a part-time basis. I never hit it off with Beveridge, though I recognised from the beginning that he was a man of extraordinary ability. I once, and only once, pleased Beveridge. I said that he "ruled over an empire on which the concrete never set". He was so delighted with this remark that he constantly quoted it, always attributing it, however, to Eileen Power, with whom, like everyone else, I assume was more or less in love. Eileen, indeed, was one of the most attractive women I have ever known. She was good-looking, and carried her erudition as a medieval scholar with wit and grace. She wrote delightfully, her account of the domestic life of nunneries would never bore anyone, and her Medieval People showed that careful scholarship can be made popular and achieve large sales.

We used to speculate on whether she would marry; on the whole the betting was that an air ace would carry her off her feet, but in the end it was the excellent historian, Michael Postan, on whom the choice fell. There was no one who did not deeply regret her loss when she died suddenly of heart failure.

(13) In his book Father Figures, Kingsley Martin describes how C. P. Scott asked him to join the Manchester Guardian.

C. P. Scott wrote he had long been looking for a leader writer and would I take C. E. Montague's place on the Manchester Guardian at a salary commencing at £1,000 a year. This was an extraordinary offer from C. P. Scott, who usually thought anyone should pay for the privilege of writing for the Manchester Guardian.

(14) In his autobiography Editor, Kingsley Martin explained the influence that Leonard Woolf had on the New Statesman (1968)

Leonard Woolf had a powerful influence on the policy and character of the New Statesman. He had been literary editor of the Nation, to which I had often contributed in the past. I had known him and Virginia Woolf ever since the First World War, and found him, as I still do, the most companionable of men. He was already to advise me and became, I think, something of a Father Figure to me. No one was ever so ready for argument and, I must add, so obstinate and lovable.

(15) Kingsley Martin, Father Figures (1966)

Arnold Bennett was a director of the New Statesman and immensely proud of being a director of the Savoy Hotel as well. He was one of the very kindest of men, with a formidable stutter. He would begin a sentence and stop. If you looked at him you found yourself staring straight down his gullet. He gave a lunch party to the other directors at the Savoy, at the same time rather embarrassingly putting me through my paces.

"What are your... p-p-politics?"

I said, rather too timidly, for I did not know his politics, that I should call myself a Socialist. "I should hope so," said Bennett, as if it would be disgraceful to be anything else.

I was appointed editor only just before Arnold Bennett died, unexpectedly and I believe unnecessarily. I persuaded the board to appoint David Low in his place; that was the beginning of a long friendship.

(16) After thirty years as editor of the New Statesman, Kingsley Martin described his contribution to the development of the journal.

My own contribution, it seems to me looking back today, was first high spirits and second "a concern for fine and often unpopular causes". Clifford Sharp once said that the New Statesman should have an 'attitude' to public affairs rather than a 'policy'. That suited me. I was a political hybrid, a product of pacifist nonconformity, Cambridge scepticism, Manchester Guardian Liberalism, and London School of Economics Socialism.

Always a poor man, I combined in myself many of the inconsistencies and conflicts of the period which long tried to reconcile pacifism with collective security, and a defence of individual liberty with the necessity of working with Communists against Fascists. I suppose my prime attitude was a dissenter's. A dissenter sees the world is bad and expresses his moral indignation.

This was rather the Nation aspect of my training than the New Statesman part. Like Massingham, I tended to be angry. War was always the ultimate horror, and I could not bear to be silent about the sufferings of minorities and cruelty inflicted on individuals, even when the aggressors were my friends. At times the paper became more than anything else the voice of the minorities and a vehicle of protest. It also had a constructive, Socialist side.

In general we supported the Left Wing of Labour. Our independence was infuriating to the leaders of the party. Politicians think in terms of votes, and do not understand that in the long run it is the climate of opinion that matters. Herbert Morrison, whom I backed wrongly as I realised later, against Attlee as leader of the party in 1935, was often very angry with me; he thought a Socialist paper ought to be putting the case for the Labour Party without reservation and bringing people along to the polls. He didn't see that it was the teachers and preachers of all types who as a result of steady reading of the paper were converted to Socialism. It was they who became the real backbone of the party, and not the mass who could be swayed one way or the other by propaganda.