Slade School of Art

The Slade School of Art was founded in 1871 with money left by Felix Slade, a wealthy art collector from Yorkshire. The first professor of art at the Slade was Edward Poynter who favoured the French academic system. Teaching methods under Poynter tended to concentrate on drawing and painting from the living model, the development of critical intelligence and an understanding of art history.

When Edward Poynter was replaced by Alphonse Legros in 1876, students were mainly taught by demonstration. In 1892 Frederick Brown succeeded Alphonse Legros as professor of fine art Slade Art School. According to Anne Pimlott Baker: "Continuing the teaching and liberal outlook of Poynter and Legros, he (Brown) built up the school of drawing, and tried to develop the individuality of his pupils, while encouraging them to study form by means of an analytical rather than an imitative approach to draughtsmanship, returning to the methods of masters such as Ingres. He attracted a strong teaching staff, establishing the principle that all teachers should be practising artists."

Frederick Brown convinced Henry Tonks to give up medicine and become one of its teachers. Tonks' biographer, Lynda Morris, has argued: "Tonks used his anatomical knowledge to teach life drawing as a swift and intelligent activity. He referred his students to old master drawings at the British Museum and taught his pupils to draw the model at the size it was seen, measured at arm's length (sight size), which enabled them continually to correct the drawing for themselves, against a physical object." Brown also recruited his friend, Philip Wilson Steer, to the staff.

Under the leadership of Brown and Tonks the Slade School of Art produced some of its most eminent artists including William Rothenstein, Augustus John, William Orpen, Paul Nash, Wyndham Lewis, Hugh Slater, Spencer Gore, Jacob Epstein, David Bomberg, Michel Salaman, Albert Rothenstein and Ambrose McEvoy.

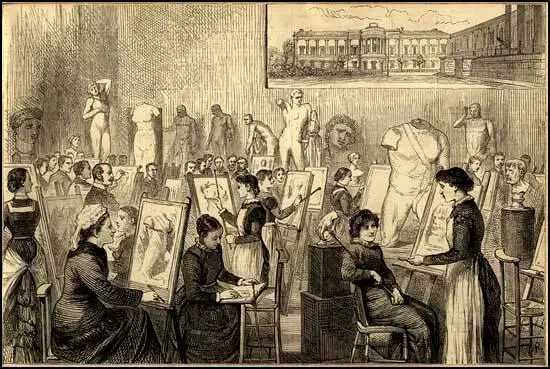

The Slade School of Art was a place that welcomed women students. This included: Gwen John, Edith Downing, Emily Ford, Bertha Newcombe, Dora Carrington, Dora Meeson Coates, Dorothy Brett, Ursula Tyrwhitt, Ida Nettleship and Gwen Salmond.

in 1881. The female students are shown drawing from plaster casts of antique classical statues.

The inset picture on this illustration shows The Slade School of Fine Art in the North Wing

of London's University College.

In the period before the First World War a small group of students worked very closely together. This included Mark Gertler, Christopher Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, John S. Currie, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee. This group became known as the Coster Gang. According to David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009), this was "because they mostly wore black jerseys, scarlet mufflers and black caps or hats like the costermongers who sold fruit and vegetables from carts in the street".

Another important tutor at the Slade School of Art was Roger Fry. He took a keen interest in all forms of art. In May 1910 he wrote an article for The Burlington Magazine on drawings by African Bushman, where he praised their sharpness of perception and intelligence of design. David Boyd Haycock argued that "Fry was opening up his awareness to a wider sphere of artistic expression, though it was not one that would win him many friends." Henry Tonks remarked to a friend: "Don't you think Fry might find something more interesting to write about than Bushmen." Tonks was also highly critical of Cubism. Tonks declared: "I cannot teach what I don't believe in. I shall resign if this talk about Cubism does not cease; it is killing me." This attitude increased the view that he had become a reactionary.

In 1910 Fry, Clive Bell and Desmond MacCarthy went to Paris and after visiting "Parisian dealers and private collectors, arranging an assortment of paintings to exhibit at the Grafton Galleries" in Mayfair. This included a selection of paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, André Derain and Vincent Van Gogh. As the author of Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "Although some of these paintings were already twenty or even thirty years old - and four of the five major artists represented were dead - they were new to most Londoners." This exhibition had a marked impression on the work of Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Spencer Gore.

Henry Tonks told his students that although he could not prevent them visiting the Grafton Galleries, he could tell them "how very much better pleased he would be if we did not risk contamination but stayed away". The critic for The Pall Mall Gazette described the paintings as the "output of a lunatic asylum". Robert Ross of The Morning Post agreed claiming the "emotions of these painters... are of no interest except to the student of pathology and the specialist in abnormality". These comments were especially hurtful to Fry as his wife had recently been committed to an institution suffering from schizophrenia.

Paul Nash recalled that he saw Claude Phillips, the art critic of The Daily Telegraph, on leaving the exhibition, "threw down his catalogue upon the threshold of the Grafton Galleries and stamped on it." William Rothenstein also disliked Fry's post-impressionist exhibition. He wrote in his autobiography, Men and Memories (1932) that he feared that the excessive publicity that the exhibition received, would seduce younger artists from "more personal, more scrupulous work".

Gilbert Spencer, the brother of Stanley Spencer, was another who studied at the Slade. He later wrote how Henry Tonks "talked of dedication, the privilege of being an artist, that to do a bad drawing was like living with a lie, and he proceeded to implant these ideals by ruthless and withering criticism. I remember once coming home and feeling like flinging myself under a train, and Stan telling me not to mind as he did it to everyone." Tonks later admitted: "I certainly cannot draw, though I have a passion for drawing; I am uncertain about the direction of lines; I have no skill of hand, and to express myself at all I have the greatest difficulty. Perhaps it is that being so deficient myself, I have enough honesty to urge my students to strengthen themselves where I am weak."

Tonks developed a reputation for being very harsh with his students. Randolph Schwabe has argued: "Once I witnessed an odd scene. A new student had come into the Antique Room, a very tall, heavy man, in private life an amateur pugilist. He sat as others did on a low seat near the floor, doing his untutored best to render the cast in front of him. Tonks, from his great height, bent over him and said cuttingly - I suppose you think you can draw. The student collected himself, rose slowly to an even greater height than Tonks and, looking down, replied with suppressed fury (but perfect justice) - If I thought I could draw - I shouldn't come here, should I? He had the better of the encounter. Tonks had nothing to say, and left the room."