Arthur McManus

Arthur McManus was born in 1889. As a young man he became a socialist and trade-unionist. He eventually became one of the leaders of the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), an organization that had been inspired by the writings of Daniel De Leon, the man who helped establish the International Workers of the World (IWW). Other leaders of the SLP included John S. Clarke, Willie Paul, James Connally and Tom Bell.

McManus became joint editor of The Socialist. In 1911 he became involved in the Clydesbank Singer sewing machine factory dispute, in which 10,000 workers went out on strike in protest at the company's decision to cut the pay of the workforce. Singers broke the strike in three weeks. McManus was considered to be one of the ring-leaders and along with 500 other workers, including Willie Paul, he lost his job at the company.

In 1915 a group of Scottish socialists, including McManus, Willie Gallacher, John Muir, David Kirkwood, and John MacLean, formed the Clyde Workers' Committee, an independent organisation of the rank and file. The CWC attempted to confront Government demands over dilution and conscription.

Arthur McManus was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. In December 1915 McManus spoke at an anti-conscription rally in George Square, Glasgow. All the speakers were arrested on public order offences but were later released without charge.

In January 1916 McManus visited Derby to meet his old friend, Willie Paul. Soon afterwards McManus and Paul joined forces with Alice Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Winnie Mason, Hettie Wheeldon and William Wheeldon to established a network in Derby to help those conscientious objectors on the run or in jail.

McManus was a member of the Clyde Workers' Committee (CWC) and in February 1916 he became involved in a dispute at Beardmores Munitions Works in Parkhead. The government claimed that the strike was a ploy by the CWC to prevent the manufacture of munitions and therefore to harm the war effort. On 25th March, McManus, David Kirkwood, Willie Gallacher and other members of the CWC were arrested by the authorities under the Defence of the Realm Act. Once again Sir Frederick Smith was the prosecutor. Tom Bell argued that: "It is doubtful if a more spiteful, hateful enemy of the workers ever existed... he threatened to send them to the front to be shot." The men were eventually court-martialled and sentenced to be deported from Glasgow to Edinburgh.

On 10th March 1917 Alice Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason were found guilty of conspiracy to murder David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson. Alice was sentenced to ten years in prison. Alfred got seven years whereas Winnie received "five years' penal servitude." These people were active members of the network that McManus had helped establish in Derby in 1916.

Senior members of the CWC, including Willie Gallacher, David Kirkwood and Arthur McManus helped organize production in Beardmore's Mile End Shell Factory. Kirkwood later remarked: "What a team! We organized a bonus system in which everyone benefited by high production... The factory, built for a 12,000 output, produced 24,000. In six weeks, we held the record for output in Great Britain, and we never lost our premier position.

John MacLean was opposed to this strategy. He wrote: "Lloyd George's purpose is to coax you to relax your Trade Union rules about non-union workers. The dangers... are the weakening of your unions and the lowering of your wages." Tom Bell agreed with MacLean and he concentrated his energies on improving the pay and conditions of the workforce. In 1917 he led a national strike of engineers and foundry workers in their demand for a forty-seven hour week. Bell joined forces with Willie Gallacher to form the Clyde Emergency Committee (CEC) to run the strike. Bell traveled to London and successfully carried out successful negotiations with the Ministry of Munitions.

In the 1918 General Election, McManus stood unsuccessfully for the Socialist Labour Party in Halifax. McManus had been impressed with the achievements of the Bolshevik Government following the Russian Revolution and in April 1920 he joined forces with Tom Bell, Willie Gallacher, Arthur Horner, Harry Pollitt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Rajani Palme Dutt, Hubert Inkpin and Willie Paul to establish the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers.

On 1st June 1920 McManus married Hettie Wheeldon at Brentford Register Office. Hettie, who had been working as a shop assistant in Chiswick, was the daughter of McManus' old friend, Alice Wheeldon. The couple set up home at 1 Beddington Terrace, Mitcham Road, Croydon. Five months after her wedding, Hettie gave birth to Sonya. Unfortunately the baby died the following day. On 10th November 1920 Hettie McManus became ill with appendicitis. She died three days later of heart failure.

In 1922 McManus attended a special conference of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (Comintern), at which it was decided to reorganise the party. He also attended the Fourth Congress of the Comintern in September, at which he was elected to its Executive Committee and Praesidium.

In October 1924 the MI5 intercepted a letter signed by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, and McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were urged to promote revolution through acts of sedition. Vernon Kell, head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson head of Special Branch, were convinced that the Zinoviev Letter was genuine. Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret but someone leaked news of the letter to the Times and the Daily Mail.

The letter was published in these newspapers four days before the 1924 General Election and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald and the Labour Party. After the election it was claimed that two of MI5's agents, Sidney Reilly and Arthur Maundy Gregory, had forged the letter and that Major Joseph Ball (1885-1961), a MI5 leaked it to the press. In 1927 Ball went to work for the Conservative Central Office where he pioneered the idea of spin-doctoring.

Research carried out by Gill Bennett in 1999 suggested that there were several MI5 and MI6 officers attempting the bring down the Labour Government in 1924, including Stewart Menzies, the future head of MI6.

On 4th August 1925, McManus and 11 other activists, Jack Murphy, Wal Hannington, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, John R. Campbell, Hubert Inkpin, Harry Pollitt, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, William Gallacher and Tom Bell were arrested for being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain and charged with violation of the Mutiny Act of 1797.

John R. Campbell later wrote: "The Government was wise enough not to rest its case on the activity of the accused in organising resistance to wage cuts, but on their dissemination of “seditious” communist literature, (particularly the resolutions of the Communist International), their speeches, and occasional articles. Campbell, Gallacher and Pollitt defended themselves. Five of the prisoners who had previous convictions, Gallacher, Hannington, Inkpin, Pollitt and Rust, were sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment and the others (after rejecting the Judge’s offer that they could go free if they renounced their political activity) were sentenced to six months." It was believed that this was a deliberate action of the government to weaken the labour movement in preparation for the impending General Strike.

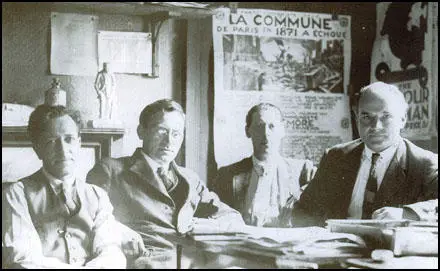

Harry Pollitt, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Hubert Inkpin; (Front Row)

John R. Campbell, Arthur McManus, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, Tom Bell.

After McManus was released he travelled to Brussels to attend the founding conference of the League Against Imperialism.

Arthur McManus died of influenza at the Royal Free Hospital on 2th February, 1927. His remains were interred in the Kremlin Wall.

Primary Sources

(1) Arthur McManus, The Communist (5th August 1920)

The Convention more than surpassed the best of my expectations. The feeling created was that, after all, everything involved in its preparation had been well worth while. The atmosphere was intense, with the earnestness and determination of the delegates. To preside over such a convention was a pleasure indeed, because however delicate the moments may have been, and these I can assure were many, the sincerity of all was demonstrated by the willing and ready assistance rendered to the chair. The value of the work done is inestimable at the moment, but of one thing I feel sure. It will bring more hope and gladness to the soul of our struggling comrades in Russia and elsewhere, than anything else which has been done in this country.

The decisions were all well taken, and while I may have felt a pang of disappointment at being on the losing side on the Labour Party issue, I must say the battle was fought with healthy vigour and clean frankness, which augers well for the Communist Party. We demonstrated that we were all capable of disagreeing, and that, to my mind, was not the least important manifestation of the Convention. The victorious side were generous to a defeated foe in a moment of victory, while my own erstwhile colleagues at least demonstrated how they could take a defeat. One impression I should like to definitely clear as gathered from Sunday’s experience, and that is, that those arguing for affiliation to the Labour Party did not urge for, nor contemplate working with, the Labour Party.

The antagonists to the Labour Party was general, but those for affiliation held the opinion that such antagonism would be best waged within their own camp. This much in fairness to the other side. There exist no sides now, but separate opinions only within the Communist Party. We are ready now for the real work.

(2) The Zinoviev Letter (October 1924)

A settlement of relations between the two countries will assist in the revolutionizing of the international and British proletariat not less than a successful rising in any of the working districts of England, as the establishment of close contact between the British and Russian proletariat, the exchange of delegations and workers, etc. will make it possible for us to extend and develop the propaganda of ideas of Leninism in England and the Colonies.

(3) Charles Trevelyan believed that the Zinoviev letter was responsible for Labour's defeat in the 1924 General Election. His friend, Francis Hirst, wrote about the matter to him on 3rd November 1924.

I will be utterly disgusted if the Labour Cabinet timidly resign with probing the mystery (of the Zinoviev letter) and explaining it to Parliament. It's the biggest electoral swindle. I personally believe you were right in denouncing it boldly as a forgery.

(4) Bertrand Russell, was the Labour Party candidate at Chelsea in the 1924 General Election. In her autobiography, The Tamarisk Tree, Dora Russell explains why she believes Labour lost the election.

The Daily Mail carried the story of the Zinoviev letter. The whole thing was neatly timed to catch the Sunday papers and with polling day following hard on the weekend there was no chance of an effective rebuttal, unless some word came from MacDonald himself, and he was down in his constituency in Wales. Without hesitation I went on the platform and denounced the whole thing as a forgery, deliberately planted on, or by, the Foreign Office to discredit the Prime Minister.

(5) Arthur McManus, James Connolly, The Socialist Review (October 1923)

I suppose it will be a very long time indeed before Connolly has his true place in history accorded to him, due undoubtedly, as Desmond Ryan himself claims in his new book recently published on James Connolly, to the “partisan claims on his corpse.” This, in a way, constitutes in itself a remarkable tribute to Connolly. The self-sacrificing character of the man’s whole life and work, his optimism in moments of darkness and when things looked very black indeed, and his valour, fortitude and courage in action, these have impressed themselves deep down on the affection of the mass of the people of Ireland. It is, therefore, natural that sects and movements should hasten to claim him as their own. But how any historian can accord their claims even a moment’s reflection, surpasses me.

Here is a man whose whole life was unquestionably devoted very definitely to work in, and on behalf of, the revolutionary working class movement; whose studies in this direction had been so profound as to place him as one of the outstanding international figures of our movement; whose activities had been so essentially working class, as to have him recognised in many lands as a great revolutionary leader of working class struggle. And yet, because he finds himself fighting side by side in an incident which lasted only a few weeks, with men of other professions and faith, his corpse has become the subject for “partisan claims.” For cool effrontery, there is not much in history to equal this. Even the author himself, despite his protest, falls a victim to it, and commits the same error as those against whom he complains. He also would claim Connolly’s corpse, and it is amazing to note that he claims it for the Irish Free State! Well, I shall be pardoned for endeavouring to re-claim Connolly from the body-snatchers, and back to the movement of Connolly’s own choosing, the revolutionary working class movement.

It is true that he was associated with the rising of 1916. It is also true that this rising was of an essentially Nationalist character. It is true that during the fighting his recorded moments of joy or sadness, were of the character of a great Irishman doing battle for his country, and it is also noteworthy, that, when he was dying he is said to have observed to his daughter, “The socialists will never understand why I am here; they will all forget that I am an Irishman.” Upon the basis of the above truths rests the whole misunderstanding, and misrepresentation of Connolly. Of much more significance, however, is how Connolly came to be there at all, and to anyone who understands the working class movement, and understands Connolly’s place and life’s activity in that movement - more particularly Connolly’s leadership of the Irish workers in the eventful years beginning with 1914 - there exists no problem at all.

(6) J. T. Murphy, The Communist International (30th March, 1927)

The death of Arthur McManus has come as a great shock to every member of our Party and to every comrade who has known him in the ranks of the Communist International. He was a lovable comrade and had won his way into the affections, not only of our Party, but also to a large number of workers outside its ranks. That his death is at loss to our Party and to the whole working class is beyond question.

Born of working class parents in Belfast some thirty-eight years ago, from his early days he was nurtured amidst all the appalling conditions attendant upon the slums of the great industrial towns. In his early years his parents moved from Belfast to Glasgow, another city with indescribable conditions in its working class areas. How well I remember visiting his home in the East End of Glasgow! I am acquainted with working class quarters of many of the industrial towns in Britain, but I know of none so appalling in its harshness and grim poverty as the East End of Glasgow. I saw more bootless, rickety children inside twenty-four hours in this region of Glasgow than I have seen anywhere else in this region of Glasgow than I have seen anywhere else in Britain.

The tenement system prevails in housing accommodation, and the overcrowding is terrible. The black smoke of the factories pours through the streets and adds to the abounding misery of the population. It as in the midst of these conditions that comrade McManus grew from boyhood to manhood. He was a child of the working class, he grew with it, shared to the full all its hardships, and died in its service. The working class have thus lost a son, a comrade and a fighter.

He had hardly become a youth ere he shed his religious associations, derived from his Irish Catholic parentage, and had become acquainted with the revolutionary socialist movement through the Marxian Educational Classes by the Socialist Labour Party. He joined this Party and rapidly became known as an agitator, a tutor of Marxian classes and an able exponent of the party policy. He carried this work into the factories with great energy, and in the days when the Socialist Labour Party attempted to build an industrial union known as the “Industrial Workers of Great Britain” no one played more energetic and faithful part in the efforts to swell its ranks as a revolutionary organisation.

It was in this life of Socialist activity that McManus became a friend of James Connolly, to whom he was undoubtedly indebted for much of his training and for his appreciation of the role of the national struggle in the revolution. Being of Irish parentage, he was naturally interested in the Irish struggle for independence and no doubt this played an important part in his long attachment to Connolly and in his repeated efforts to assist in building an Irish Socialist Party along with Connolly. He therefore followed keenly all the phases of the Irish struggle and was one of the few Socialists in Britain who appreciated the role of Connolly in British Socialist history.

His main work however did not lie in Ireland but in Britain. He was best known to the workers as a pioneer of the Shop Steward and Workers’ Committee movement and as the first Chairman of the Communist Party. In his workshop activities he was one of the first men in the Socialist Labour Party to appreciate the limitations of the Party policy in relation to industrial unionism. The necessity for the workers to find a new outlet for the ventilation of their grievances, and a new means of struggle in view of the fettering of the trade union machine to the apparatus of the State for the duration of the war, was the historical explanation of the sudden rise of the Shop Stewards to prominence in the early days of the war. It was this new situation which produced such a dynamic mass movement that convinced McManus and others of the need to depart from the sectarianism which had dominated the Socialist Labour Party. He became a member of its Executive and later, in the growth of the Shop Stewards Movement into a national organisation, he became its first chairman.

After his arrest and deportation, along with a number of others in 1915, he became widely known throughout England as well as Scotland. He participated in many strikes during the war period, and after being arrested again in 1917 during the great engineers’ dispute which served to popularise him amongst the mass of engineering workers, his work during the whole of this period consisted of a fight against the sectarianism in the Socialist Labour Party, of pioneering new ways of fighting the trade union bureaucracy, of applying the principles of industrial unionism to the immediate struggle, and at the same time utilising the apparatus of the old trade unions.

His next important piece of work was his activity on behalf of the creation of a Communist Party. He was profoundly influenced, as many more of us were, by the Russian Revolution. It threw such a great light upon our own experiences that we could not help seeing that our conception of a party was mainly that of a propagandist body, enunciating principles, exposing capitalism and the class war, but not understanding how to lead it.

I remember that it was comrade McManus who first persuaded me to join a political party. We met in the midst of industrial struggles in 1916 and were amazed to find how we had been pioneering similar ideas without contact with each other. But still neither of us appreciated the role of the Party at that time, as we were brought to understand it by the experiences of the Russian Revolution. Nevertheless once we were convinced of this we set to work towards the fusion of the Socialist Parties into a Communist Party.

Comrade McManus, comrade Bell, comrade Paul, comrade Stoker and myself became a Unity Committee of the Socialist Labour Party in 1918. In all the negotiations which took place, in all the internal Party fights for the purpose of getting a united Communist Party, McManus played a leading role. He was exceedingly capable as a negotiator and could be counted upon to eliminate the personal friction in the negotiations and secure a discussion of principle.

Indeed, we can say that from 1918 to 1923, when the Communist Party decided to do without a chairman, comrade McManus played the leading role in bringing together and consolidating the Socialist forces into a Communist Party. He was the first chairman of the Communist Party and his first task in the first two years was to complete what had been begun in the negotiations with the British Socialist Party and the other groups which had come together in the Unity Conference. It was no mean achievement to have succeeded in leading these elements into a united party, and history accords to him the honour therefore of two important achievements - the leading role in a mass movement of workers during the war and the leading of the revolutionary forces which laid the foundations of the Communist Party.

He was not a writer nor an organiser, but he was an able agitator and a good tactician and, although after the Party reorganised in 1923 it ceased to have a chairman, he was a member of the Political Bureau from that time onwards and for a period the representative of the Party on tee Executive Committee of the Communist International. In all the outstanding moments of Party experiences and struggles, he has been well to the front and played his part. His first serious breakdown in health was in 1923. From that time onwards he has never been really a healthy man. His experiences in prison by no means helped him to recover, but immediately he came out he resumed his activity as a leader of the party, plunged into the activities of the General Strike and the miner’s struggle, and upon his shoulders fell a good deal of the responsibility for the conduct of the Party’s agitation in its “Hands Off China” campaign. He attended the Anti-Imperialist Conferenceat Brussels, having come straight from mass agitation at the docks in various ports. Within a few days after the Brussels Conference comes the news of his death. He thus died in harness, a good comrade, an energetic fighter—living, working and fighting under the banner of the Communist International. He will not be forgotten, nor will his work cease, for it was a part of the struggle of the working class for freedom.