Heywood Broun

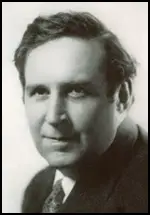

Heywood Broun, the third son of Heywood Cox Broun, was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 7th December, 1888. His father was an Scottish immigrant who had developed a successful printing business in the city. His mother, the former Henrietta Brose, was the daughter of a German-American broker. According to one source she was "well-educated, gracious, and a firm-willed woman with strong opinions on practically everything."

Dale Kramer has suggested: "He grew up with an omnipresent sense of sin.... His hypersensitivity was offsett by a natural gregariousness. He perfected the defensive mechanism of poking fun at himself, approaching other boys with a shy, humorous look, ready to break into a grin if kidding began." Richard O'Connor, the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) has pointed out: "Broun attended an excellent private school, Horace Mann, to which he rode on the horsecars every morning, for both his elementary and secondary education. By the time he reached the high school years he was taller and heavier than most of his classmates, over six feet tall and weighing about 190 pounds, but he was ill coordinated, like many boys who grow too fast. His style of dress, then and later, was haphazard. He had a mischievous sense of humor and was popular with his contemporaries, qualities which proved enduring." Broun had an inspiring English teacher, Helen Baker, who persuaded Heywood to become editor of the school newspaper. He later recalled that at the age of fourteen he made up his mind that he would make a career in journalism.

Broun went to Harvard University in 1906 where he became friends with John Reed, Walter Lippmann, Alan Seeger, Hans von Kaltenborn, Owen Davis, Robert Edmond Jones and Lee Simonson. In May 1908 Lippmann and eight other students decided to organize a socialist discussion group. Broun joined but at this stage in his life he did not consider himself a socialist. However, he did enjoy going to meetings hearing speakers such Lincoln Steffens, Florence Kelley, Morris Hillquit and Benjamin Flower.

Broun came under the influence of Charles Townsend Copeland. Broun's biographer, Richard O'Connor has pointed out: "Professor Charles Townsend Copeland was a small, waspish, and bitterly witty man... Copeland vigorously advocated in youthful writers the search for that lean, sinewy quality which distinguished American prose from its English ancestry, and the impact he made on a generation of Harvard students was tremendous."

However it was another student, John Reed, who mainly benefited from Copeland's teaching. He later wrote: "Copeland had a great deal to do with the making of John Reed. Copey did not know, and no one of us knew, that this humorous, light-hearted youngster would burn himself up in a fever of revolution. We believe only a few things which Reed believed. As a political economist he did not inspire admiration, but he stuck closely to the creed which an artist ought to have as any man we have ever known. He wrote what he felt. Copey did not groan in vain for this pupil."

After leaving Harvard University in 1910, Broun found work as a sports reporter for the New York Morning Telegraph, where he was able to report on his baseball heroes, Tris Speaker, Duffy Lewis, Chris Mathewson and Harry Hooper. His starting salary was $20 a week. The sports editor was Bat Masterson, the former gunfighter, army scout, gambler and sheriff at Dodge City. Broun claimed that he sometimes wore a .45-caliber revolver when one of his old enemies was in town.

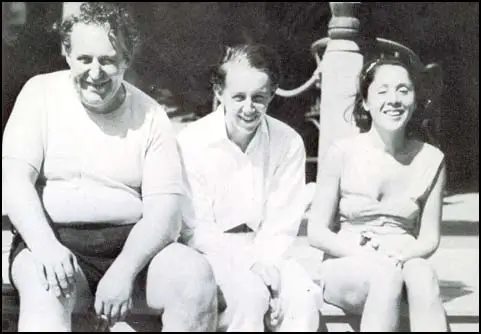

Jerome Beatty, Heywood Broun, Damon Runyon, Larry Semon and Sam Crane.

In 1912 Broun went to work with the New York Tribune. Although he enjoyed writing about sport Broun had a strong desire to be a foreign correspondent like the much admired Richard Harding Davis. His first assignment was in Shanghai to report on the new government of Sun Yat-sen. He later recalled that while in China he was able to employ his considerable skills as a poker player: "A couple of United States marines introduced me to a poker game which we played with a group of Chinese merchants. Only one of them could speak English, but they all thought they knew the value of the hands. It turned out that I had made a good bargain for myself by agreeing to go to China without salary and simply on an expense account."

Broun continued as a sports reporter until 1915 when he was appointed as the newspaper drama critic. At the time he regarded George Bernard Shaw as the greatest living playwright. He told his friend, McAllister Coleman, that he liked his "brother-of-man angle". According to Richard O'Connor he was also "interested in and willing to grant indulgences to the experimental theaters then springing up around Washington Square and other off-Broadway locations."

In 1915 Broun met Ruth Hale at a baseball game at the Polo Grounds. The author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) argued: "From the moment he was introduced to Ruth Hale, he was intrigued by her - perhaps she reminded him of his strong-minded mother. Ruth was not a conventional beauty, but she had a striking face with large gray eyes and dark blond hair and a slender, willowy figure. Her vitality, her candor, her mental vigor and intellectual curiosity - and her combativeness - were apparent the moment you met her. She must have been the least coy, the least subtle female ever to emerge from the ranks of Southern womanhood. She laid it all on the line, take it or leave it. She challenged, questioned, hammered away at every preconception, particularly those affecting the male attitude toward her sex."

Hale worked as a reporter for the New York Times and a drama critic for Vogue. She was also a militant feminist and a member of the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS). Broun later recalled that they argued a great deal about feminism: "Nobody ever defeated Miss Hale in an argument. The dispute was about feminism. We both agreed that in law and art and industry and anything else you can think of men and women should be equal. Ruth Hale felt that this could be brought about only through the organization of women along sex lines." They became close friends and often took long walks together in Central Park.

Broun was very impressed when he saw Lydia Lopokova in The Antick, a play by Percy MacKaye. His review the next morning showed how much he enjoyed her performance: "We regret now wasted adjectives and we pine for every superlative with which we have lightly parted. All words denoting, connoting or appertaining in any way to charm we would bestow upon Lydia Lopokova... She is the most charming young person who has trod the stage in New York this season. But she did not tread. She did not even walk. She skipped, she danced, she pranced, and, like as not, she never touched the stage. Or so it seemed."

Broun invited Lopokova out to dinner. As the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) has pointed out: "Thereafter Heywood pursued a headlong courtship, took her walking afternoons in Central Park, to supper after the nightly performance. They were the original odd couple: the tiny sophisticated Russian ballerina and the hulking Broun in his raccoon coat and black hat. Other admirers of the Russian girl couldn't understand what she saw in the ungainly Broun in eternal dishabille, but women had and would always find him attractive in a teddy-bear sort of way. He appealed to their maternal instincts. The first thought any woman had on glimpsing Broun was that he needed taking care of - and reforming. His tousled hair and his off-center necktie, his slightly forlorn air, his generally unkempt condition (despite his mother's continuing efforts) recommended even to a Russian dancer-actress intent on her own career the need for someone to take Heywood in hand."

Lopokova accepted Broun's proposal of marriage. He told his friend Franklin Pierce Adams, who reported in the New York Evening Mail: "Heywood Broun, the critic, I hear hath become engaged to Mistress Lydia Lopokova, the pretty play actress and dancer. He did introduce her to me last night and she seemed a merry elf." However, the relationship was not to last as soon after she fell in love with Randolfo Barocchi who she did marry. She later recalled "my professional career involved me in a whirl of excitement. I felt I did not want to be tied up to Heywood - so I broke it off, hurting him very much at the time, I am sorry to say."

Broun now asked Ruth Hale to marry him. She agreed but only on the agreement that it would be a marriage of equals. She would retain her identity and independence. She would also continue to pursue her own career and that they would be co-equal heads of the household. Broun wanted children but Hale insisted that he would have to be satisfied with only one child. The couple were married on 7th June, 1917. Hale told Broun that "she was not and would never be known as Mrs. Broun; she was and always would be Ruth Hale."

Immediately after the wedding, Broun and Hale travelled to France to report on the First World War. Broun for the New York Tribune and Hale for the Chicago Tribune. They arrived with the first U.S. troop-bearing convoy. Their first articles covered the arrival at Saint-Nazaire of the American Expeditionary Forces but the American censor, Major Frederick Palmer, sat on their stories for five days on the theory that the arrival of the convoy would be of crucial interest to the enemy. Palmer objected to a passage in Broun's report where he claimed that the first remark of the first soldier to land was: "Do they allow enlisted men in the saloons in this town". Broun refused to remove it, arguing that his account made the soldiers more human. Palmer eventually allowed the article to be published.

Broun continued to have problems with Major Frederick Palmer. On grounds of military security, the journalists were forbidden to mention any name in the dispatches but General John J. Pershing. No military units could be identified in their reports. Nor were they allowed to write negatively about the morale of the soldiers, their equipment and the quality of trench life. This caused problems for Broun because as Richard O'Connor pointed out: "Heywood did not intend to write dissertations on strategy and tactics or flag-waving propaganda for the Allied cause. He regarded himself as a reporter, not a standard-bearer for patriotism."

Ruth Hale returned to the United States in December 1917 to give birth to her son (Heywood Hale Broun). The following month Broun arrived back in New York City. He then wrote a series of articles for the New York Tribune without the risk of interference from censorship. Broun argued that troops on the Western Front were lacking guns, boots, warm clothing and decent food and "a proper and intelligent public opinion should not tolerate it". As a result of his complaints the supply system of the United States Army was reformed. He also published two books on the war, The American Expeditionary Forces (1918) and America in the War: Our Army at the Front (1918).

During the First World War three journalists, Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley, who all worked at Vanity Fair, began taking lunch together in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was around six feet tall, Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ."

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

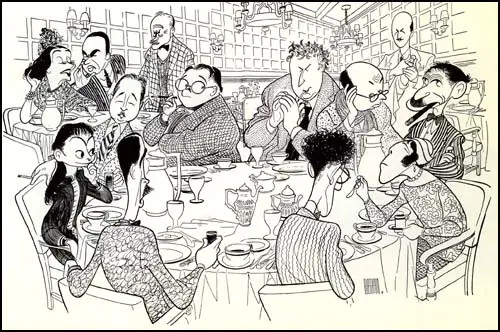

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso , the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received. The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel."

Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre. That, I might add, was no means cement for the gathering at any time... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

Heywood Broun and his wife, Ruth Hale, often attended these lunches. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table. Other regulars at these lunches included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. .

The group played games while they were at the hotel. One of the most popular was "I can give you a sentence". This involved each member taking a multi syllabic word and turning it into a pun within ten seconds. Dorothy Parker was the best at this game. For "horticulture" she came up with, "You can lead a whore to culture, but you can't make her think." Another contribution was "The penis is mightier than the sword." They also played other guessing games such as "Murder" and "Twenty Questions". A fellow member, Alexander Woollcott, called Parker "a combination of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth." Arthur Krock, who worked for the New York Times, commented that "their wit was on perpetual display."

Edna Ferber wrote about her membership of the group in her book, A Peculiar Treasure (1939): "The contention was that this gifted group engaged in a log-rolling; that they gave one another good notices, praise-filled reviews and the like. I can't imagine how any belief so erroneous ever was born. Far from boosting one another they actually were merciless if they disapproved. I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and wholeheartedly. Their standards were high, their vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and very, very tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters. The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists, and the socially pretentious. They were ruthless towards charlatans, towards the pompous and the mentally and artistically dishonest. Casual, incisive, they had a terrible integrity about their work and a boundless ambition."

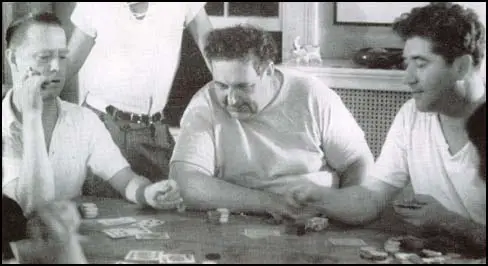

Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), has argued: "The Algonquin profited mightily by the literary atmosphere, and Frank Case evinced his gratitude by fitting out a workroom where Broun could hammer out his copy and Benchley could change into the dinner coat which he ceremonially wore to all openings. Woollcott and Franklin Pierce Adams enjoyed transient rights to these quarters. Later Case set aside a poker room for the whole membership." The poker players included Broun, Alexander Woollcott, Herbert Bayard Swope, Robert Benchley, Harold Ross, Franklin Pierce Adams, George S. Kaufman, Deems Taylor, Laurence Stallings, Harpo Marx, Jerome Kern and Prince Antoine Bibesco. On one occasion, Woollcott lost four thousand dollars in an evening, and protested: "My doctor says it's bad for my nerves to lose so much." It was also claimed that Harpo Marx "won thirty thousand dollars between dinner and dawn". Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972) has argued that Broun, Adams, Benchley, Ross and Woollcott were all inferior poker players, Swope and Marx were rated as "pretty good" and Kaufmann was "the best honest poker player in town."

Margaret Chase Harriman, the author of The Vicious Circle The Story of the Algonquin Round Table (1951) wrote that Broun was an important member of the group: "At thirty-three, Broun was a bewildering and bewildered, but peculiarly lovable, mass of contradictions. He was gently bred, slovenly of person, soft-hearted, steel-minded, evasive and direct, brave and terrified, considerate and tough, gregarious and solitary. His face, under its tangled crown of mattered curls, had an intangible beauty of feature, and the soul enclosed in last week's laundry was, of course, the soul of a shining knight. Broun was the greatest of infracaninophiles, or lovers of the underdog."

In 1921, Broun's wife, Ruth Hale, established the Lucy Stone League. The first list of members included only fifty names. This included Heywood Broun, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Franklin Pierce Adams, Anita Loos, Zona Gale, Janet Flanner and Fannie Hurst. Its principles were forcefully expressed in a booklet written by Hale: "We are repeatedly asked why we resent taking one man's name instead of another's why, in other words, we object to taking a husband's name, when all we have anyhow is a father's name. Perhaps the shortest answer to that is that in the time since it was our father's name it has become our own that between birth and marriage a human being has grown up, with all the emotions, thoughts, activities, etc., of any new person. Sometimes it is helpful to reserve an image we have too long looked on, as a painter might turn his canvas to a mirror to catch, by a new alignment, faults he might have overlooked from growing used to them. What would any man answer if told that he should change his name when he married, because his original name was, after all, only his father's? Even aside from the fact that I am more truly described by the name of my father, whose flesh and blood I am, than I would be by that of my husband, who is merely a co-worker with me however loving in a certain social enterprise, am I myself not to be counted for anything."

Hale became involved in a campaign against the New York City Council when it attempted to pass an ordinance prohibiting women from smoking in restaurants. Hale also insisted that she and Broun lived on separate floors of their three-story house. Broun agreed that men had an equal responsibility for bringing up children: "Most things that have to be done for children are the simplest sort. They should tax the intelligence of no one. Men profess a total lack of ability to wash baby's face simply because they believe there's no great fun in the business at either end of the sponge."

However, Broun admitted in Seeing Things at Night (1921) that they received a great deal of help bringing up their son, Heywood Hale Broun: "I have no feeling of being a traitor to my sex, when I say that I believe in at least a rough equality of parenthood. In shirking all the business of caring for children we have escaped much hard labor. It has been convenient. Perhaps it has been too convenient. If we have avoided arduous tasks, we have also missed much fun of a very special kind. like children in a toy shop, we have chosen to live with the most amusing of walking-and-talking dolls, without ever attempting to tear down the sign which says, Do not touch."

During this period, Broun's friend, McAllister Coleman, tried to persuade him to join the Socialist Party of America. Although a great admirer of Eugene Debs, he initially rejected the idea: "I like the brotherhood-of-man angle... If I ever get convinced that Socialism will work and really usher in brotherhood I'll probably join up. But Marx was an atheist. I'm a believer. At that, I may be some kind of Christian Socialist."

In the summer of 1921, Herbert Bayard Swope, the editor of the New York World, invited Broun to work for his newspaper. Swope told Broun: "What I try to do in my paper is to give the public part of what it wants and part of what it ought to have whether it wants it or not." Swope had recruited a significant number of columnists, most of them on a three-times-a-week basis. This included Alexander Woollcott , William Bolitho , Franklin Pierce Adams, Deems Taylor, Samuel Chotzinoff, Laurence Stallings, Harry Hansen and St. John Greer Ervine. Swope's biographer, Ely Jacques Kahn, has argued: "Its contributors were encouraged by Swope, who never wrote a line for it himself, to say whatever they liked, restricted only by the laws of libel and the dictates of taste. To keep their stuff from sounding stale, moreover, he refused to build up a bank of ready-to-print columns; everybody wrote his copy for the following day's paper."

Broun began writing a column entitled It Seems To Me on 7th September 1921. Swope did not tell Broun what he should write, only that it be provocative, controversial and outspoken. Over the next few years Broun campaigned against censorship and racial discrimination and for academic freedom. He also supported those like Eugene V. Debs, Margaret Sanger, John T. Scopes and D. H. Lawrence who were persecuted in the United States for their political and social views. Broun also campaigned for the release of Tom Mooney and the Scottsboro Nine.

Franklin Pierce Adams became a close friend during this period: "Broun was a debunker of any kind of pretentiousness, political, official, or literary... He hated injustice and intolerance; seldom did he dislike those he considered unjust or intolerant. He was a lion in print, but a lamb in his personal relationships. Men whom he attacked in print would invite him to lunch; he'd go, and the victim of his wrath would fall to his charm. Heywood, for twenty years or so, must have earned lots of money. He cared less for money than anyone I knew."

On 30th April 1922, the Algonquin Round Tablers produced their own one-night vaudeville review, No Siree!: An Anonymous Entertainment by the Vicious Circle of the Hotel Algonquin . It was opened by Heywood Broun who appeared before the curtain "looking much like a dancing bear who had escaped from his trainer". He was followed by a monologue by Robert Benchley, entitled The Treasurer's Report . Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman contributed a three-act mini-play, Big Casino Is Little Casino , that featured Robert E. Sherwood. The show also included several musical numbers, some written by Irving Berlin. One of the most loved aspects of the show was the Dorothy Parker penned musical numbers that were sang by Tallulah Bankhead, Helen Hayes, June Walker and Mary Brandon.

New York Times assigned the actress, Laurette Taylor, to review the show. She suggested that the lot of them to give up any theatrical ambitions, but if they persisted in placing themselves on public view, "I would advise a course of voice culture for Marc Connelly, a new vest and pants for Heywood Broun, a course with Yvette Guilbert for Alexander Woollcott... I suppose there must have been some suppressed indignation in my heart to see the critics maligning my stage, just as there will be at my daring to sit and judge as a critic."

In 1923 Ruth Hale purchased Sabine Farm, in Stamford, Fairfield County. The original farm had three houses set a couple of hundred yards apart. Dale Kramer, later recalled: "The kind of people who till soil for a living would have called it a farm. A large portion was trees and brush and swamp an an acre or so of the rest was a shallow lake... The independence of the partners in the marriage was becoming ever more firmly established. Since Broun hadn't come in on the farm, it was necessary for him to make special arrangements to visit or board."

In the summer of 1924 the New York World published a series of articles investigating the activities of the Ku Klux Klan. It mainly concentrated on its unconcealed campaign against Jews and Catholics, naturally a matter of great concern in New York City with its large Jewish and Catholic populations. Broun joined the crusade and denounced the KKK as a cowardly and un-American organization. On 4th July, Broun found a burning cross outside his home in Connecticut but he refused to stop writing about this issue. Broun wrote: "We must bring ourselves to realize that it is necessary to support free speech for the things we hate in order to ensure it for the things in which we believe with all our heart."

Broun launched an attack of William Jennings Bryan, America's most prominant politician who supported the KKK, when he addressed a rally on their behalf in June, 1924: "For William Jennings Bryan is the very type and symbol of the spirit of the Ku Klux Klan. He has never lived in a land of men and women. To him this country has been from the beginning peopled by believers and heretics. According to his faith mankind is base and cursed. Human reason is a snare, and so Bryan has made oratory the weapon of his aggressions. When professors in precarious jobs have disagreed with him about evolution, Mr. Bryan has never argued the issue, but instead has turned bully and burned fiery crosses at their doors." Broun also criticised Bryan for not opposing Jim Crow laws.

Broun was a great admirer of Eugene V. Debs, the leader of the American Socialist Party, who had been imprisoned during the First World War because of his pacifist beliefs: When he died in October 1926 he wrote in the New York World: "Eugene V. Debs is dead and everybody says that he was a good man. He was no better and no worse when he served a sentence at Atlanta. I imagine that now it would be difficult to find many to defend the jailing of Debs. But at the time of the trial he received little support outside the radical ranks. The problem involved was not simple. I hated the thing they did to Debs even at the time, and I was not then a pacifist... Free speech is about as good a cause as the world has ever known. But, like the poor, it is always with us and gets shoved aside in favor of things which seem at some given moment more vital. They never are more vital. Not when you look back at them from a distance. When the necessity of free speech is most important we shut it off. Everybody favors free speech in the slack moments when no axes are being ground."

Broun went on to argue: "Eugene Debs was a beloved figure and a tragic one. All his life he led lost causes. He captured the intense loyalty of a small section of our people, but I think that he affected the general thought of his time to a slight degree. Very few recognized him for what he was. It became the habit to speak of him as a man molded after the manner of Lenin or Trotsky. And that was a grotesque misconception... Though not a Christian by any precise standard, Debs was the Christian-Socialist type. That, I'm afraid, is outmoded. He did feel that wrongs could be righted by touching the compassion of the world. Perhaps they can. It has not happened yet.... The Debs idea will not die. To be sure, it was not his first at all. He carried on an older tradition. It will come to pass. There can be a brotherhood of man."

John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1975) has argued that Heywood Broun, as a popular columnist, with national syndication, greatly helped in spreading the influence of the Algonquin Round Tablers. "His friends thought coloured Mr. Broun's own thinking. When he therefore spoke to his several million readers, Mr. Broun was not giving them just an Eastern seaboard point of view, but a specifically Round Table point of view... The Algonquinites could cause to be published, and could comment on, such new writing as, for example, that of the Paris group, and thereby help to create a climate in which it would find acceptance."

Broun had campaigned for the release of Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco after they were convicted for murdering Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli during a robbery. In 1927 Governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-member panel of Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuel W. Stratton, and the novelist, Robert Grant to conduct a complete review of the case and determine if the trials were fair. The committee reported that no new trial was called for and based on that assessment Governor Fuller refused to delay their executions or grant clemency. Walter Lippmann, who had been one of the main campaigners for Sacco and Vanzetti, argued that Governor Fuller had "sought with every conscious effort to learn the truth" and that it was time to let the matter drop.

It now became clear that Sacco and Vanzetti would be executed. Broun was furious and on 5th August he wrote in New York World: "Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate. What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution."

The following day Broun returned to the attack. He argued that Governor Alvan T. Fuller had vindicated Judge Webster Thayer "of prejudice wholly upon the testimony of the record". Broun had pointed out that Fuller had "overlooked entirely the large amount of testimony from reliable witnesses that the Judge spoke bitterly of the prisoners while the trial was on." Broun added: "It is just as important to consider Thayer's mood during the proceedings as to look over the words which he uttered. Since the denial of the last appeal, Thayer has been most reticent, and has declared that it is his practice never to make public statements concerning any judicial matters which come before him. Possibly he never did make public statements, but certainly there is a mass of testimony from unimpeachable persons that he was not so careful in locker rooms and trains and club lounges."

However, it was his comments on Abbott Lawrence Lowell that caused the most controversy: "From now on, I want to know, will the institution of learning in Cambridge which once we called Harvard be known as Hangman's House?" The New York Times complained in an editorial that Broun's "educated sneer at the President of Harvard for having undertaken a great civic duty shows better than an explosion the wild and irresponsible spirit which is abroad".

Herbert Bayard Swope, the editor was on holiday and Ralph Pulitzer, the owner of the New York World, decided to stop Broun writing about the case after a board meeting on 11th August. As Richard O'Connor, the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975) has pointed out: "The editorial board's decision certainly was defensible if one takes into account the climate of the twenties... The country was acutely aware of what some newspapers termed the Red Menace, now that all hope that the Bolshevik dictatorship in Moscow might crumble or be overthrown had vanished."

On 12th August 1927 Pulitzer published a statement in the newspaper: "The New York World has always believed in allowing the fullest possible expression of individual opinion to those of its special writers who write under their own names. Straining its interpretation of this privilege, the New York World allowed Mr. Heywood Brown to write two articles on the Sacco-Vanzetti case, in which he expressed his personal opinion with the utmost extravagance. The New York World then instructed him, now that he had made his own position clear, to select other subjects for his next articles. Mr. Broun, however, continued to write on the Sacco-Vanzetti case. The New York World, thereupon, exercising its right of final decision as to what it will publish in its columns, has omitted all articles submitted by Mr. Broun."

Broun was not willing to be censored and asked for his contract to be terminated. Pulitzer refused and reminded him that his contract contained a passage that meant he could not work for any other newspaper for the next three years. Broun now went on strike. On the 27th August, 1927, Pulitzer wrote: "Mr. Broun's temperately reasoned argument does not alter the basic fact that it is the function of a writer to write and the function of an editor to edit. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred I publish Mr. Broun's articles with pleasure and read them with delight; but the hundredth time is altogether different. Then something arises like the Sacco-Vanzetti case. Here Mr. Broun's unmeasured invective against Gov. Fuller and his committee seemed to the New York World to be inflammatory, and to encourage those revolutionists who care nothing for the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti, nor for the vindication of justice, but are using this case as a vehicle of their propaganda. The New York World, for these reasons, judged Mr. Broun's writings on the case to be disastrous to the attempt, in which the New York World was engaged, of trying to save the two condemned men from the electric chair. The New York World could not conscientiously accept the responsibility for continuing to publish such articles... The New York World still considers Mr. Broun a brilliant member of its staff, albeit taking a witch's Sabbatical. It will regard it as a pleasure to print future contributions from him. But it will never abdicate its right to edit them."

Broun was not allowed to write for a newspaper Oswald Garrison Villard to write a weekly page of comment and opinion for The Nation. While he was away the circulation of the New York World dropped dramatically. Samuel Hopkins Adams blamed the crisis on the inexperienced Ralph Pulitzer: "Joseph Pulitzer had made a disastrous will, taking control of the paper from two sons (Joseph II and Herbert) who were able and devoted journalists, and vested it in the cadet of the family, an amiable playboy."

Herbert Bayard Swope managed to persuade Broun to return and his first column was on 2nd January 1928. The dispute changed the image of the New York World. As Ely Jacques Kahn, the author of The World of Swope (1965) pointed out: "the shining integrity of the op ed page seemed to have been irreparably, if not fatally, tarnished" by the temporary silencing of Broun and the suspicion would linger that the columnists weren't absolutely free to speak their minds.

Broun admitted that his wife Ruth Hale played an important role in writing his column. He later wrote: "She was not my severest critic. Her tolerance was broad to the mass of mediocre stuff the newspaper hack is bound to produce in seventeen years. Nobody else, I suppose, ever gave me such warm support and approbation for those afternoons when I did my best. She made me feel ashamed when I faltered, and I suppose that for seventeen years practically every word I wrote was set down with the feeling that Ruth Hale was looking over my shoulder."

The drama critic, George Oppenheimer, a close friend of Broun and Hale, later recalled they made an excellent partnership: "Forgetful, sloppy and neurotic, he had inherent goodness, a crusading courage against ills and injustices, and a loyalty rare in mankind. He was a knight in ill-fitting, slightly rusty armor, but a knight nonetheless... It was Ruth Hale who, more often than not, buckled on Heywood's armor and sent him into battle. Not that he had to be pushed, but Ruth was a fellow crusader and thought up new causes and new crusades for him to pursue."

Broun and Hale were both strong supporters of birth-control. These views were not shared by Ralph Pulitzer who was frightened by the power of the Roman Catholic Church in New York City. Fearing that he would be censored, Broun wrote an article about the subject in The Nation. He argued: "In the mind of the New York World there is something dirty about birth control. In a quiet way the paper may even approve of the movement, but it is not the sort of thing one likes to talk about in print... There is not a single New York editor who does not live in mortal terror of the power of this group (Roman Catholic Church). It is not a case of numbers but of organization."

Pulitzer was furious with Broun for exposing the censorship concerning the discussion of birth-control and on 3rd May, 1928, Broun's column was missing from the New York World. Instead it included the following statement: "The New York World has decided to dispense with the services of Heywood Broun. His disloyalty to this newspaper makes any further association impossible."

Roy W. Howard, the owner of the New York Telegram, was one of many who offered to employ Broun. Dale Kramer the author of Heywood Broun (1949) has pointed out: "Roy Howard, the pompadoured, mustachioed young chairman of the Scripps-Howard board, was more persistent than anyone else. Broun would be of enormous assistance in Howard's ambition to make good in his venture into New York journalism... Broun's basic demand was freedom of expression. While about it, he was hopeful of reaching his goal of thirty thousand a year."

Howard agreed these terms and next to Broun's first column he wrote: "Ideas and opinions expressed in this column are those of one of America's most interesting writers, and are presented without regard to their agreement or disagreement with the editorial attitude of this paper". Robert Paine Scripps added: "Since Mr. Broun is writing under his own signature, we do not care what he writes as long as it is not libelous and as long as it is interesting." It is claimed that Broun was such a popular writer that his column increased sales of the newspaper by 50,000.

On 8th May 1928, Broun took up the case of Mary Ware Dennett, who had been arrested, charged with producing pornographic literature, convicted, and sentenced to 300 days in jail. Broun supported her booklet, The Sex Side of Life, and claimed that she had been convicted "because she dared to say that love was beautiful. Some reformers hold that this is true but that the fact should be kept quiet in the presence of adolescents."

Carl Van Doren, in an article for Century Magazine, placed Broun at the top of the list of political columnists in the United States. He argued that Broun was popular because "of his liberal attitudes which were attuned to the current literary fashion; liberalism was holding sway over the educated people while conservatism was intellectually impoverished and unable to appeal to the popular imagination". Roy W. Howard accepted Broun's importance and increased his salary from $30,000 to $40,000. Only Walter Winchell and Dorothy Thompson earned that sort of money from their newspaper writings.

During the 1928 Presidential Election he supported Al Smith against Herbert Hoover. Under the influence of his friend, McAllister Coleman, he became a Christian Socialist. Broun was hugely impressed by the books of Edward Bellamy and encouraged his friends to read Looking Backward. (1888) and Equality (1897). Another favourite during this period was George Bernard Shaw and approved of his sentiments expressed in An Intelligent Women's Guide to Socialism (1928).

At the end of 1928 Ruth and Heywood agreed to separate but not to divorce. According to one source: "Neither had any moral or religious antipathy for divorce, but it seemed somehow, an unfriendly act." They sold their house in New York City and moved into separate quarters. even so they were separated only by seven or eight blocks that lay between her apartment on East 51st Street and his penthouse flat on West 58th Street.

McAllister Coleman eventually recruited Broun into the Socialist Party of America. After reading the work of Edward Bellamy, George Bernard Shaw and Jack London, he considered himself a Christian Socialist. As Richard O'Connor, the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975), has pointed out: "He (Broun) believed Socialism was the creed most likely to usher in the brotherhood of man, but like any civilized fellow, he was dismayed by the oppressions dictated by the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist variation in Soviet Russia. He liked the idea of Christian Socialism, not because he was all that ardent a Christian but because it seemed to promise a less fanatical and doctinaire sort of governing power."

In 1930 became the socialist candidate that took on Ruth Baker Pratt the Republican Party incumbent of the 17th District of New York. The Democratic Party candidate was Louis B. Brodsky. Some of those who campaigned for Broun included Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Walter Winchell, Floyd Gibbons, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Floyd Dell, Clarence Darrow, Elmer Rice, John Dewey, James Weldon Johnson, Stuart Chase, Frank Crowninshield, George Gershwin, Deems Taylor, Charles MacArthur, Fred Astaire, Carl Van Doren, Irving Berlin, Ina Claire, Alfred Lunt, Lynn Fontanne and Irvin S. Cobb. The writer, Theodore Dreiser, also worked for him but commented to Woollcott: "Why he wants to descend to Congress is beyond me. No power lies there. The power and direction comes from elsewhere."

One of those who objected to Broun's participation in the election was his boss, Roy W. Howard. He published an article in the New York Telegram explaining why Broun should stay out of politics. Broun summarized his complaints as "(1) No Scripps-Howard feature writer has ever gone to Congress. (2) The odds seem to be overwhelmingly against my election. (3) The profession of journalism is more important than that of politics. (4) Independence of thought precludes party membership."

In an article published on 19th August, 1930, Broun defended his candidacy: "The real sticking point is party affiliation. I am quite sure that the fact of its being Socialist does not enter into the problem. Surely it would be far more embarrassing for a liberal newspaper to have its columnist affiliated with the Tammany machine or the Republican organization of Sam Koenig than to be serving under the leadership of Norman Thomas... But I am tired of hearing all this talk about how the honest average citizen should get into politics and not leave it to the machine professionals. I am tired of hearing this, because I am average and honest and yet, when I do get in, my own boss tells me that this is no business for me. It's everybody's business and nobody's business. But I am even more tired of standing with well-meaning liberals weaving a daisy chain of good intentions. I want to break that chain and enlist for duration. Here goes!"

During the campaign Broun was arrested while taking part in a demonstration in favour of 15,000 striking garment workers. Broun only spent two hours in custody. Although it gave him extra publicity it did not help his popularity. Richard O'Connor has argued: "Broun's arrest did not impress the old-guard Socialists who had suffered real punishment in the back rooms of police stations after being locked up for picketing or demonstrating in bygone struggles." Ruth Baker Pratt won the election with 19,899 votes. Louis B. Brodsky finished a close second with 19,248. Broun finished a poor third with 6,662 votes.

Broun continued to be a popular columnist. It has been estimated that his work for the New York Telegram increased circulation by 50,000, whereas New York World had lost readers since his departure. Franklin Pierce Adams, was responsible for trying to replace Broun, has argued: "Dozens of pinch-hitters, substitutes, and more or less permanencies did their three-a-week best... I took a shot at getting people to write for it during the summer of 1930, and people on the staff always gave it to me for the Broun column. I want it on the record that firing Broun, for anything, was a mistake."

In December 1930 Ralph Pulitzer began negotiating with Roy W. Howard about the selling of the New York World. The sale went through and the last edition of the newspaper was published on 27th February, 1931. The Scripps-Howard organization now merged the two newspapers and gave it the name the New York World-Telegram .

Heywood Broun was worried about the merger and wrote on 28th February, 1931: "I sat and watched a paper die. We waited in the home of a man (Herbert Bayard Swope) who once had run it. A flash came over the phone. The World was ended.... The World fired me, and the Telegram gave me a job. Now, the Telegram owns the World. This is a fantastic set of chances almost like those which might appear in somebody's dream of revenge. But I never thought much of revenge. I wouldn't give a nickel for this one. If I could, by raising my hand, bring dead papers back to life I'd do so... I am a newspaperman. There are many things to be said for this new combination. It is my sincere belief that the Scripps-Howard chain is qualified by its record and its potentialities to carry on the Pulitzer tradition of liberal journalism. In fact, I'll go further and say that, as far as my personal experience goes, the Telegram has been more alert and valiant in its independent attitude than the World papers. Yet I hope, at least, that this may be the end of mergers. The economic pressure for consolidation still continues. A newspaper is, among other things, a business. And, even so, it must be more than that."

Broun admitted that he was proud to be an "agitator". In an article published on 5th May, 1931: "In recent years the word agitator is almost always used as a term of reproach. In fact, the imagination supplies the prefix red. And yet the most casual survey must show that all causes - conservative or otherwise - have been furthered by agitation. The chief complaint leveled against the agitator is that he takes people who are content with their lot and makes them dissatisfied. This is the charge hurled against labor leaders who organize strikes in districts where unionization was not heard of before... Many wholly conservative people subscribe large sums of money for foreign missions. Now, obviously, the missionary is always an agitator. He may go to a South Sea island where trousers are quite unknown and stir the savages into putting on garments by making them ashamed of their previous lack of attire." He went on to argue that many famous Americans such as William Lloyd Garrison were agitators: "And no one would deny the reasonableness of fastening the title of agitator to William Lloyd Garrison. In fact, in his case, the epithet was constantly employed by the slaveholders of the South. It was their argument that Negroes who had never even known a dream of freedom were merely rendered restless by the strong words of the man in Boston. And restless they did become as the tingle of the abolition movement began to prick against dead nerve centers.... And since this process of honoring the despised and the criticized has become so universal, we might sharpen our wits enough to refrain from hasty condemnation of all who would shake us out of lethargy. They may be disturbing. They may be a nuisance. But they are the corpuscles of the corporate being through which the waste and the stagnation of the status quo is turned into living tissue."

In the early 1930s Heywood Broun stopped going to the Algonquin Hotel after complaining that some members of the Round Table, including George S. Kaufman and Ina Claire, had undermined a strike by filling in as waiters in the dining room. Margaret Chase Harriman, the author of The Vicious Circle The Story of the Algonquin Round Table (1951), has pointed out: "The emotional lives of many of them had grown so complex as to interfere with their gags... Perhaps it was politics, and a broadening sense of public issues, that helped to break up the Round Table... As the small, independent worlds we all used to live in gradually expanded and fused into One World with its one vast headache, there was no longer any room for cozy little sheltered cliques of specialists... The day of the purely literary or artistic group was over, and so was the small, perfect democracy of the Algonquin Round Table."

Broun was totally opposed to capital punishment. In an article published on 9th December 1931 he tried to answer the question: ""Why is there always sympathy for the criminal and none for his victim?" Broun claimed: "The answer is easy. The dead lie beyond our pity. By quelling the heartbeat of the assassin we do not set up a rhythm in the breast of the one who was stabbed. And if we pluck out the eye of an offender there does not exist a socket into which it may fit with any utility.... We deal in depreciated currency. Nobody profits either in a spiritual or a material sense by the transaction... In all reason just what has he paid which is in any way tangible? Far from paying, he has been allowed - even compelled - to welsh out of a settlement. His crime constitutes an offense against certain individuals and against the community, and by all means I would have him pay. But the payment will have to be by service. Instead of being made to die he should be compelled to sweat."

Richard O'Connor has argued: "Heywood Broun made himself one of the most eloquent and revered totems of the liberalism of his time, perhaps because he typified its yearnings and unrealized hopes. He had many of the virtues of the modern liberal, chiefly the shared conviction that mankind is good and inherently perfectible, and some of the flaws, chiefly an excessive optimism and an intolerance for anyone professing a grubbier sense of reality."

Broun continued to campaign against the conviction of people on false charges. This included trade union leader, Tom Mooney, who had been imprisoned for the San Francisco bombing on 22nd July, 1916. He was also involved in the campaign to free Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems, Clarence Norris, Andy Wright, Ozzie Powell, Olen Montgomery, Eugene Williams and Willie Roberson (known as the Scottsboro Nine) who had been convicted of rape in 1931.

Broun was expelled from the Socialist Party of America after appearing with members of the Communist Party at a rally demanding the release of these men. Broun wrote in the New York World-Telegram on 29th April 1933: "I don't expect the Communists to love me, and I'm not going to love them. I hope from time to time to say many things about them, and I expect the same in return. But I think it would be a fine idea not to fight until Tom Mooney is free and the Scottsboro boys are acquitted."

In August 1933, Broun joined forces with McAllister Coleman, Lewis Gannett, George Britt, Joseph Cookman, Doris Fleeson, Edward J. Angly, Allen Raymond, Frederick Woltman and Carl Randau to establish the American Newspaper Guild in an attempt to improve the wages of journalists. During this period many reporters were only paid $15 a week. Roy W. Howard, was bitterly opposed to the unionization of his employees and was very angry with Broun for forming this guild.

In 1933 Broun and Ruth Hale resumed living together at the Hotel Des Artistes in Manhattan. They also spent more time with each other at Sabine Farm. However, although they enjoyed each other's company, Ruth found the relationship difficult. Richard O'Connor has argued: "It must have galled her to watch Broun toss off a column or an article in less than an hour while she sweated for days over a similar composition... She could not ride herself of the conviction that somehow, as long as she was married to Broun, she was deprived of her individuality, even her identity." Broun finally agreed to a divorce, which she obtained in Mexico on 17th November, 1933.

Ruth had not been in good health for sometime. Friends commented that she was so thin she was almost emaciated. She told Luella Henkel: "After forty a woman is through. I'm going to make myself die." In the summer of 1934 Ruth became ill while staying at Sabine Farm. Broun arrived to look after all but she refused to allow a doctor to be called. Ruth Hale died on 18th September.

Broun wrote in the New York Telegram the next day: "My best friend died yesterday. I would not mention this but for the fact that Ruth Hale was a valiant fighter in an important cause. Concerning her major contention we were in almost complete disagreement for seventeen years. Out of a thousand debates bates I lost a thousand. Nobody ever defeated Miss Hale in an argument. The dispute was about feminism. We both agreed that in law and art and industry and anything else you can think of men and women should be equal. Ruth Hale felt that this could be brought about only through the organization of women along sex lines.... It was a curious collaboration, because Ruth Hale gave me out of the very best she had to equip me for the understanding of human problems. She gave this under protest, with many reservations, and a vast rancor. But she gave."

On 5th January, 1935, Broun married Connie Madison. The daughter of Italian immigrants, she was the widow of Johnny Dooley, who was a member of the Ziegfeld Follies, before his death. A relative described her as being "unusually intelligent with a brilliant sense of humour... she never grew old and was always sparkling and gay". Broun later adopted Connie's nine-year-old daughter, Patricia. She later recalled: "Although he was impressive because of his size and aura of greatness, Heywood seemed shy and I took to him right away... I was happy to have a father and, after being an only child, happy to have a brother."

Broun was a strong supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. His views were not shared by his employer, Roy W. Howard and for the sake of "balance" decided to "offset Broun's liberal humanitarianism with the corrosive offerings of his opposite in ideology and temperament". Westbrook Pegler, the well-known Roosevelt hater.

In one article published on 28th November 1936 Pegler praised the lynching of Thomas Harold Thurmond and John M. Holmes that had taken place in San Jose in 1933. A mob had broken into the local jail and lynched two men who had been charged with having kidnapped and murdered Brooke Hart, the son of Alexander Hart, the owner of the Leopold Hart and Son Department Store. Pegler wrote that: "The fine theory of all expressions of horror and indignation is that punishment is not supposed to be vengeance but a protective business, whereas the rabble, which constitutes by far the greatest element of the population, want to make the murderer suffer as the victim or his family did. And, though they would be willing to let the Law do it for them if the Law could be relied upon, they know too well what lawyers will do when they get a chance to invoke a lot of legal technicalities which were written and passed by lawyers to provide lawyers with opportunities to make money."

Heywood Broun took the opposite point of view and condemned James Rolph, the governor of California, who had argued that lynching was "a fine lesson for the whole nation" and promised to pardon any man convicted of the lynching. Broun wrote: "If it were possible to carry on a case history of every person in the mob who beat and kicked and hanged and burned two human beings I will make the prophecy that out of this heritage will come crimes and cruelties which are unnumbered... To your knees, Governor, and pray that you and your commonwealth may be washed clean of this bath of bestiality into which a whole community has plunged."

Oliver Pilat, the author of Pegler: Angry Man of the Press (1963) has argued that Pegler was hostile to Broun for other reasons: "During poker games with Franklin P. Adams, Alexander Woollcott and other cronies at the Hotel Algonquin in New York, he (Broun) would ask to be excused for a couple of hands and come back with a finished column. Pegler saw this trick performed once during a poker game at Broun's own Sabine Farm north of Stamford, Connecticut, and it gave him a shock. Here was a man who played the typewriter like a professor in a honky-tonk, and yet what came out was limpid literature! To Pegler, who bled for every phrase, this was the unforgivable excellence."

Broun became a close friend of Quentin Reynolds , a sports writer on the New York Telegram. According to a mutual friend: "Reynolds patterned himself in the Broun mold, not only in his casual attitude toward the gents' tailoring industry but in his manner and political stance; he also adopted the seemingly artless and simplistic Broun literary style, which wasn't as easy to imitate as many would-be imitators hoped." Reynolds said of Broun, who at that time was earning over $1,000 a week: "Tough-minded about social justice and conditions for the working man, for example, he was indifferent to his own wages and hours and was even a markedly easy touch. A slashing writer in his columns, he appeared to many of his readers an agnostic; yet during the years I knew him he was groping toward his belief in God."

Dale Kramer, the author of Heywood Broun (1949), has pointed out: "His hatred for Hitlerism was more than intellectual and went deeper than sympathy for the victims of Nazism. Fascism could make him physically ill, and he attacked it with savage fury. Because he believed he believed the United States should co-operate with Russia against Hitler's evident plan of world conquest, and because of opposition to political discrimination in unions, he was often called a Communist, or at least a fellow-traveller."

On 22nd August, 1938, Heywood Broun was called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He had been accused of being a communist and a member of communist-front pressure groups such as the National Committee to Aid the Victims of German Fascism, the National Committee for Defense of Political Prisoners, the National Tom Mooney Council of Action and the National Scottsboro Committee of Action. Broun denied being a member of the American Communist Party but agreed that he had joined groups campaigning against the conviction of Tom Mooney and the Scottsboro Boys and the imprisonment of the political opponents of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany.

On the 28th August, 1939, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact. Broun wrote that the "masquerade is over" and it was now possible to examine objectively the "faces of the various ones who pretend to be devoted to the maintenance of democracy". The American Communist Party was now told by Moscow to change its anti-fascist stand. When Broun attacked the hypocrisy of the communists he was denounced as a "traitor to the cause."

Broun was eventually sacked by Roy W. Howard. He was immediately given a contract by the New York Post. However, the salary was less than the $49,000 he was receiving at the New York Telegram. However, before he could start work he was taken ill. Broun's friends were appalled by the decision of Westbrook Pegler to write critically about Broun while he was unable to defend himself. Without any basis of truth, Pegler accused Broun of supporting Soviet press censorship and compared him to Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler and Earl Browder, the leader of the American Communist Party: "I have seen recent superficial expressions of disappointment in Moscow, but never an outright incantation, and even if I saw one I would have to treat it the same as I treat changes of front by Stalin, Hitler and Earl Browder."

Quentin Reynolds argued that: "Broun could talk of nothing but Pegler's attack on him.... It seemed incredible that he was allowing Pegler's absurd charge of dishonesty to hurt him so. But not even Connie could make him dismiss it from his mind. The doctor told him to relax; he'd be all right if he got some sleep. But he couldn't relax. He couldn't sleep."

On 15th December Broun developed pneumonia and was taken to the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. As Richard O'Connor has pointed out: "Had antibiotics been developed a few years earlier, Broun would easily have won his struggle against the congestion in his chest. Instead his condition steadily worsened.... His temperature soared and for the next two days he was unconscious most of the time, with Connie and his son at his bedside and his friends gathered in the corridor outside or in the waiting room."

Heywood Broun died in hospital on 18th December, 1939. Westbrook Pegler went to Broun's funeral and according to his biographer, he had been "appalled by the rudeness of the reception he got from friends of Broun at the cemetery". The journalist James Kirby recalled: "Pegler saw nothing inconsistent in attending the funeral of the late Heywood Broun within a few days of his most disgraceful diatribe against the great American while Broun lay on his deathbed." Quentin Reynolds added: "I think Broun, who is dead, will live a lot longer than the little men who try to defeat ideas by hating their fellow men."

Primary Sources

(1) (1) Heywood Broun, America in the War: Our Army at the Front (1919)

Although the German Army had begun to disintegrate by November 1, the Americans saw some hard fighting after that date. The task set for Pershing's men was in theory almost as difficult as clearing the Argonne Forest. The offensive was aimed at the Longuyon-Sedan-Mezieres railway, which was one of the most important lines of communication of the German Army. Germany was aware of the gravity of this threat and used her very best troops in an effort to stop the Americans. For a time the Germans fought steadily, but their morale was waning at the end. The Americans found on several occasions that their second-day gains were greater than those of the first day, which was formerly an unheard of thing on the western front.

In the final days of the war the Americans had to go their fastest in an effort to reach Sedan before the armistice went into effect. During one phase of the battle doughboys mounted on auto-trucks went forward in a vain effort to establish contact with the enemy. The roads were so bad, however, that the Americans were unable to catch up with the fleeing Germans.

The third phase of the Meuse-Argonne campaign found the Americans absolutely confident of success. They knew their superiority over the Germans, and the American Army was constantly growing stronger while the Germans grew weaker. Pershing was able to send well-rested divisions into the battle.

The final advance began on November 1. American artillery was stronger than ever in numbers and much more experienced. Never before had our army seen such a barrage, and the German infantry broke before the advance of the doughboys. The German heart to fight had begun to develop murmurs, although there were some units among the enemy forces which fought with great gallantry until the very end. Aincreville, Doulcon, and Andevsnne fell in the first day of the attack. Landres et St. Georges was next to go, as the Fifth Corps, in an impetuous attack, swept up to Bayonville. On November 2, which was the second day of the attack, the First Corps was called in to give added pressure. By this time the German resistance was pretty well broken. It was now that the motor-truck offensive began. Behind the trucks the field-guns rattled along as the artillerymen spurred on their horses in a vain effort to catch up with something at which they could shoot. At the end of the third day of the attack the American Army had penetrated the German line to a depth of twelve miles. A slight pause was then necessary in order that the big guns might come up, but on November 5 the Third Corps crossed the Meuse. They met a sporadic resistance from German machine-gunners but swept them up with small losses. By the 7th of November the chief objective of the offensive thrust was attained. On that day American troops, among them the Rainbow Division, reached Sedan. Pershing's army had cut the enemy's line of communication. Nothing but surrender or complete defeat was left to him.

In estimating the extent of the American victory it is interesting to note that General Pershing reported that forty enemy divisions participated in the Meuse-Argonne battle. Our army took 26,059 prisoners and captured 468 guns. Colonel Frederick Palmer estimates that 650,000 American soldiers were engaged in the battle. This is a greater number than were engaged at St. Mihiel, and it was, of course, a new mark in the records of the American Army. Colonel Palmer has stated his opinion that Meuse-Argonne was one of the four decisive battles of the war. The other three which he names are the first battle of the Marne, the first battle of Ypres, and Verdun.

(2) Margaret Chase Harriman, The Vicious Circle The Story of the Algonquin Round Table (1951)

At thirty-three, Broun was a bewildering and bewildered, but peculiarly lovable, mass of contradictions. He was gently bred, slovenly of person, soft-hearted, steel-minded, evasive and direct, brave and terrified, considerate and tough, gregarious and solitary. His face, under its tangled crown of mattered curls, had an intangible beauty of feature, and the soul enclosed in last week's laundry was, of course, the soul of a shining knight. Broun was the greatest of infracaninophiles, or lovers of the underdog.

(3) Franklin Pierce Adams, Nods and Becks (1944)

Broun was a debunker of any kind of pretentiousness, political, official, or literary... He hated injustice and intolerance; seldom did he dislike those he considered unjust or intolerant. He was a lion in print, but a lamb in his personal relationships. Men whom he attacked in print would invite him to lunch; he'd go, and the victim of his wrath would fall to his charm. Heywood, for twenty years or so, must have earned lots of money. He cared less for money than anyone I knew.

(4) Heywood Broun, New York World (30th June, 1924)

In Madison Square Saturday night William Jennings Bryan testified his love of Christ and voted for the Ku Klux Klan.

Mr. Bryan explained his vote by saying that he did not think the Ku Klux Klan should be advertised in the platform of the Democratic Party. And as he pleaded against giving publicity to the Klan he stood in the glare of ten great Klieg spotlights while 15,000 in the hall, and millions outside, listened to the debate on the most fiery issue presented to any National Convention in fifty years. It was a little as if Noah, on the twenty-ninth day, had said, "Let's hush up the matter that there's been quite a spell of rain around here lately."

"You may call me a coward if you will," Mr. Bryan continued in developing his argument, "but there is nothing in my life to justify the charge that I am a coward."

That's as it may be, but it is true that Saturday night Mr. Bryan's betrayal of his country was not actuated by fear. No such kindly explanation is possible. The poor frightened woman from Georgia who changed her vote over to the forces of the Klan was afraid. She could hardly whisper the "no" which helped largely to decide the result. But Bryan spoke fearlessly in a loud, clear voice with oratorical interludes.

He did that which he wanted to do.

For William Jennings Bryan is the very type and symbol of the spirit of the Ku Klux Klan. He has never lived in a land of men and women. To him this country has been from the beginning peopled by believers and heretics. According to his faith mankind is base and cursed. Human reason is a snare, and so Bryan has made oratory the weapon of his aggressions.

When professors in precarious jobs have disagreed with him about evolution, Mr. Bryan has never argued the issue, but instead has turned bully and burned fiery crosses at their doors. Once he wrote to a friend: "We will drive Darwinism from the schools. The agnostics who are undermining the faith of our students will be glad enough to teach anything the people want taught when the people speak with emphasis. My explanation is that a man who believes he has brute blood in him will never be a martyr. Only those who believe they are made in the image of God will die for a truth. We have all the Elijahs on our side."

Of course, that is not quite true. William Jennings Bryan was a pacifist for the glory of God. Eugene V. Debs was a pacifist for the glory of man. It was Mr. Debs who went to jail.

But, true or untrue, Mr. Bryan's letter is revelatory. Jesus Christ was the first and greatest teacher of democracy because his mission in the world was to win belief. He made faith the test of the human soul. Mr. Bryan is content to compel conformity.

In the present convention the Ku Klux Klansmen were not in the least concerned with what the delegates thought about them. They were only interested in what was said. The demand was simply that the platform should be silent. Mr. Bryan can understand that philosophy.

I said that Mr. Bryan spoke fearlessly, but I will not say that he spoke truthfully. He said many things which were obviously false. His capacity for folly and misconception is great, but even so, I think he knew that he spoke falsely.

"There is not a State in the Union," he said, "where anybody whose rights are denied cannot go and find redress."

If a Negro in Mr. Bryan's Florida went to the polls and tried to vote, where could he go when his right was denied? Not to William Jennings Bryan, for Mr. Bryan is on record as giving complete approval to the policy of his adopted State in handling the race question. And so in this instance Mr. Bryan knew that he did not speak the truth.

(5) Heywood Broun, New York World (23rd October, 1926)

Eugene V. Debs is dead and everybody says that he was a good man. He was no better and no worse when he served a sentence at Atlanta.

I imagine that now it would be difficult to find many to defend the jailing of Debs. But at the time of the trial he received little support outside the radical ranks.

The problem involved was not simple. I hated the thing they did to Debs even at the time, and I was not then a pacifist. Yet I realize that almost nobody means precisely what he says when he makes the declaration, "I'm in favor of free speech." I think I mean it, but it is not difficult for me to imagine situations in which I would be gravely tempted to enforce silence on anyone who seemed to be dangerous to the cause I favored.

Free speech is about as good a cause as the world has ever known. But, like the poor, it is always with us and gets shoved aside in favor of things which seem at some given moment more vital. They never are more vital. Not when you look back at them from a distance. When the necessity of free speech is most important we shut it off. Everybody favors free speech in the slack moments when no axes are being ground.

It would have been better for America to have lost the war than to lose free speech. I think so, but I imagine it is a minority opinion. However, a majority right now can be drummed up to support the contention that it was wrong to put Debs in prison. That won't keep the country from sending some other Debs to jail in some other day when panic psychology prevails.

You see, there was another aspect to the Debs case, a point of view which really begs the question. It was foolish to send him to jail. His opposition to the war was not effective. A wise dictator, someone like Shaw's Julius Caesar, for instance, would have given Debs better treatment than he got from our democracy.

Eugene Debs was a beloved figure and a tragic one. All his life he led lost causes. He captured the intense loyalty of a small section of our people, but I think that he affected the general thought of his time to a slight degree. Very few recognized him for what he was. It became the habit to speak of him as a man molded after the manner of Lenin or Trotsky. And that was a grotesque misconception. People were constantly overlooking the fact that Debs was a Hoosier, a native product in every strand of him. He was a sort of Whitcomb Riley turned politically minded.

It does not seem to me that he was a great man. At least he was not a great intellect. But Woodward has argued persuasively that neither was George Washington. In summing up the Father of His Country, this most recent biographer says in effect that all Washington had was character. By any test such as that Debs was great. Certainly he had character. There was more of goodness in him than bubbled up in any other American of his day. He had some humor, or otherwise a religion might have been built up about him, for he was thoroughly Messianic. And it was a strange quirk which set this gentle, sentimental Middle-Westerner in the leadership of a party often fierce and militant.

Though not a Christian by any precise standard, Debs was the Christian-Socialist type. That, I'm afraid, is outmoded. He did feel that wrongs could be righted by touching the compassion of the world. Perhaps they can. It has not happened yet. Of cold, logical Marxism, Debs possessed very little. He was never the brains of his party. I never met him, but I read many of his speeches, and most of them seemed to be second-rate utterances. But when his great moment came a miracle occurred. Debs made a speech to the judge and jury at Columbus after his conviction, and to me it seems one of the most beautiful and moving passages in the English language. He was for that one afternoon touched with inspiration. If anybody told me that tongues of fire danced upon his shoulders as he spoke, I would believe it....

Something was in Debs, seemingly, that did not come out unless you saw him. I'm told that even those speeches of his which seemed to any reader indifferent stuff, took on vitality from his presence. A hard-bitten Socialist told me once, "Gene Debs is the only one who can get away with the sentimental flummery that's been tied onto Socialism in this country. Pretty nearly always it gives me a swift pain to go around to meetings and have people call me "comrade." That's a lot of bunk. But the funny part of it is that when Debs says "comrade" it's all right. He means it. That old man with the burning eyes actually believes that there can be such a thing as the brotherhood of man. And that's not the funniest part of it. As long as he's around I believe it myself."

With the death of Debs, American Socialism is almost sure to grow more scientific, more bitter, possibly more effective. The party is not likely to forget that in Russia it was force which won the day, and not persuasion.

I've said that it did not seem to me that Debs was a great man in life, but he will come to greatness by and by. There are in him the seeds of symbolism. He was a sentimental Socialist, and that line has dwindled all over the world. Radicals talk now in terms of men and guns and power, and unless you get in at the beginning of the meeting and orient yourself, this could just as well be Security Leaguers or any other junkers in session.

The Debs idea will not die. To be sure, it was not his first at all. He carried on an older tradition. It will come to pass. There can be a brotherhood of man.

(6) Heywood Broun, New York World (5th August, 1927)

When at last Judge Thayer in a tiny voice passed sentence upon Sacco and Vanzetti, a woman in the courtroom said with terror: "It is death condemning life!"

The men in Charlestown Prison are shining spirits, and Vanzetti has spoken with an eloquence not known elsewhere within our time. They are too bright, we shield our eyes and kill them. We are the dead, and in us there is not feeling nor imagination nor the terrible torment of lust for justice. And in the city where we sleep smug gardeners walk to keep the grass above our little houses sleek and cut whatever blade thrusts up a head above its fellows.

"The decision is unbelievably brutal," said the Chairman of the Defense Committee, and he was wrong. The thing is worthy to be believed. It has happened. It will happen again, and the shame is wider than that which must rest upon Massachusetts. I have never believed that the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti was one set apart from many by reason of the passion and prejudice which encrusted all the benches. Scratch through the varnish of any judgment seat and what will you strike but hate thick-clotted from centuries of angry verdicts? Did any man ever find power within his hand except to use it as a whip?

Gov. Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate.

What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution.

Already too much has been made of the personality of Webster Thayer. To sympathizers of Sacco and Vanzetti he has seemed a man with a cloven hoof. But in no usual sense of the term is this man a villain. Although probably not a great jurist, he is without doubt as capable and conscientious as the average Massachusetts Judge, and if that's enough to warm him in wet weather by all means let him stick the compliment against his ribs.