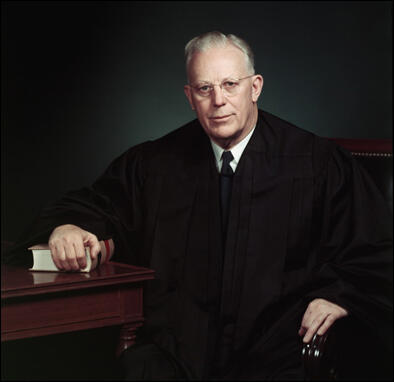

Earl Warren

Earl Warren, the son of an Norwegian immigrant who worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad, was born in Los Angeles, California, in 1891.

Warren obtained a law degree from the University of California in 1912. He worked as a lawyer in California before being elected as district attorney of Alameda County in 1925.

In November 1938 Culbert Olsen was elected as Governor of California, the first member of the Democratic Party, to hold this office for forty-four years. The following year, Warren, a member of the Republican Party, was appointed California's attorney general.

One of Olsen's first acts was to pardon Tom Mooney, a trade union leader who had been convicted of a bombing which occurred in San Francisco in 1916. Although strong evidence existed that the District Attorney of the time, Charles Fickert, had framed Mooney, the Republican governors during this period refused to order his release. In October 1939, Olsen pardoned Warren Billings, a friend of Mooney's who had also been imprisoned for the bombing.

Warren had disagreed with Olsen's actions. As a member of the state Judicial Qualifications Commission, he blocked confirmation of the Olsen's nominee to the state Supreme Court, Max Radin, a man he considered to be too radical for this post.

Warren also upset liberals and supporters of human rights by the role he played in dealing with people of Japanese descent during the Second World War. Most of these people lived in California. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, these people were classified as enemy aliens. Warren, as attorney general, urged that these people should be interned.

On 29th January 1942, the U.S. Attorney General, Francis Biddle, established a number of security areas on the West Coast in California. He also announced that all enemy aliens should be removed from these security areas. Three weeks later President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the construction of relocation camps for Japanese Americans being moved from their homes.

Over the next few months ten permanent camps were constructed to house more than 110,000 Japanese Americans that had been removed from security areas. These people were deprived of their homes, their jobs and their constitutional and legal rights. Warren later confessed: "I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens. Whenever I thought of the innocent little children who were torn from home, school friends and congenial surroundings, I was conscience-stricken."

Warren's extreme views on internment was popular with most people in California and this enabled him to defeat Culbert Olsen as governor in 1943. He held the post for the next ten years. He was also selected as running-mate for Thomas Dewey in 1948. However, Dewey was defeated by Harry S. Truman in the election.

Warren hoped to become the Republican Party's candidate in the 1952 presidential election. He lost out to Dwight D. Eisenhower who went on to become president. Warren was rewarded for his loyalty by being appointed by Eisenhower to the post of chief justice of Supreme Court.

Over the next few years Warren made it clear he supported the civil rights campaign and voted for the banning segregation in America's schools. He now became a target of right-wing groups and Robert Welch, the leader of the John Birch Society, described Warren as being a member of a Communist conspiracy. Other white supremacists such as George Wallace and James Eastland joined in these attacks. At one rally in Los Angeles there were calls for Warren to be lynched.

After the death of John F. Kennedy in 1963 his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." Johnson asked Warren if he would be willing to head the commission. Warren refused but it was later revealled that Johnson blackmailed him into accepting the post. In a telephone conversation with Richard B. Russell Johnson claimed: " Warren told me he wouldn't do it under any circumstances... I called him and ordered him down here and told me no twice and I just pulled out what Hoover told me about a little incident in Mexico City... And he started crying and said, well I won't turn you down... I'll do whatever you say."

Other members of the commission included Gerald Ford, Allen W. Dulles, John J. McCloy, Richard B. Russell, John S. Cooper and Thomas H. Boggs.

The Warren Commission reported to President Johnson ten months later. It reached the following conclusions:

(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

(2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

(5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

(6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(7) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

(8) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the US Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(9) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone.

In 1966 Warren made another landmark decision when he ruled that criminal suspects be informed of their rights before being questioned by the police.

Earl Warren retired from the Supreme Court in 1969, and died in 1974, at age 83.

Primary Sources

(1) Telephone conversation between Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard B. Russell (8.55 p.m 29th November, 1963)

Richard Russell: I know I don't have to tell you of my devotion to you but I just can't serve on that Commission. I'm highly honoured you'd think about me in connection with it but I couldn't serve on it with Chief Justice Warren. I don't like that man. I don't have any confidence in him at all.

Lyndon B. Johnson: It has already been announced and you can serve with anybody for the good of America and this is a question that has a good many more ramifications than on the surface and we've got to take this out of the arena where they're testifying that Khrushchev and Castro did this and did that and chuck us into a war that can kill 40 million Americans in an hour....

Richard Russell: I still feel it sort of getting wrapped up...

Lyndon B. Johnson: Dick... do you remember when you met me at the Carlton Hotel in 1952? When we had breakfast there one morning.

Richard Russell: Yes I think so.

Lyndon B. Johnson: All right. Do you think I'm kidding you?

Richard Russell: No... I don't think your kidding me, but I think... well, I'm not going to say anymore, Mr. President... I'm at your command... and I'll do anything you want me to do....

Lyndon B. Johnson: Warren told me he wouldn't do it under any circumstances... I called him and ordered him down here and told me no twice and I just pulled out what Hoover told me about a little incident in Mexico City and I say now, I don't want Mr. Khrushchev to be told tomorrow (censored) and be testifying before a camera that he killed this fellow and that Castro killed him... And he started crying and said, well I won't turn you down... I'll do whatever you say.

(2) Joachim Joesten, The Dark Side of Lyndon Baines Johnson (1968)

He (H. L. Hunt) was shocked because Johnson had appointed Chief Justice Warren to head the Commission three days after the Communist Daily Worker, in a front-page statement, had suggested it. That Johnson did not follow this advice in order to accommodate the Communists, but for a truly Machiavellian purpose, was something bound to escape the limited intellect of an H. L. Hunt.

Hunt was scared to death, and for apparently good reason, for Earl Warren had, immediately after the assassination, publicly expressed the opinion that this foul deed was the work of right-wing extremists. His anxiety grew when investigators for the Warren Commission found out that one of his boys, Nelson, had paid for that despicable ad in The Dallas Morning News, while another, Lamar, maintained a cozy business and social relationship with the notorious pimp and murderer Jack Ruby.

What the old man didn't realize is that the Commission, in this as in a score of other cases, simply sought to establish the damaging facts in order to be better able to suppress them and to shield effectively those responsible for the assassination. How Lyndon B. Johnson ever managed to get a man like Earl Warren so abjectly to prostitute his great name and prestige, remains the only real mystery of Dallas. But he did it and thus managed to fool, at least for a few years, public opinion throughout America and the world.

After the Warren Report had been released, Hunt heaved a deep sigh of relief. When reporters asked him how he felt about it, Hunt replied, 'It's a very honest document.' And that, coming from H. L. Hunt, is about the most damning thing anybody has ever said about the Warren Report.

(3) George de Mohrenschildt, I'm a Patsy (1977)

Allen Dulles, head of CIA at the time, who did not interfere in the procedings but was there as a distant threat. Judge Warren himself, a rather sympathetic, paternal figure who had a weakness for Marina, we found later. Representative General Ford, friendly and youthful-looking. The last ten years changed him considerably. And then innumerable, hustling lawyers, all of them trying to figure out how a single man, Lee Harvey Oswald, could have done so much damage with his old, primitive, Italian army rifle. Having around such a galaxy of legal and political talent, you don't have to be tortured, you would impressed and intimidated to say almost anything about an insignificant, dead ex-Marine.

And during my lengthy deposition, I said some unkind things about Lee which I now regret. The reader must imagine my situation, sitting there and answering an endless flow of well prepared and insiduous questions for more than two days.... Was this an intimidation?

"We know more about your life than you yourself, so answer all my questions truthful and sincerely," Jenner began.

I should have said, "if you know everything why bring us all the way from Haiti?" But I did not and began to talk. And my answers were very nicely edited in the subsequent Report. "Say the whole truth and nothing but the truth," he intoned.

Jenner was a good actor, very cold and aloof at first, he switched to flattery and smiles when he felt that I was getting tensed up and antagonistic. "How cosmopolitan you are! How many important people you know! Yes, you are great!" said Jenner ingratiatingly. And probably this flattery worked well on me, proving to me that Albert Jenner was such a good friend of mine. So I answered all the questions to the best of my ability, with utter sincerity, without even asking to have my lawyer present and he, the sneaky bastard, did not say a word that the whole testimony would be printed and distributed all over the world. And so my privat life was shamelessly violated. During this time Jeanne and the dogs were languishing in the old Willard Hotel.

At the end of this long testimony Jenner seemed convinced that I was not involved in any way in this "already solved" assassination. He began showering compliments on me and I felt like a star of a pornographic movie. Before leaving, I told Jenner of the harm this affair was causing me, mainly of the attitude of the American Ambassador. Of the reflexion on my work in Haiti. He inserted therefore some nice statements, putting me above all suspicion. Big deal! The harm was already done. And how could I have been suspected of anything, being so far away from Dallas, unless President Duvalier and I used vodoo practices and inserted needles or shot at a doll resembling President Kennedy. Since everything was known, Jenner concluded my useless testimony with the following words: "You did all right. Keep up the life you have been living. You helped a poor family." And he added as an aside "remember, sometimes it is dangerous to be too generous with your time and help."

(4) The Warren Commission Report (September, 1964)

(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository. This determination is based upon the following:

Witnesses at the scene of the assassination saw a rifle being fired from the sixth-floor window of the Depository Building, and some witnesses saw a rifle in the window immediately after the shots were fired.

The nearly whole bullet found on Governor Connally's stretcher at Parkland Memorial Hospital and the two bullet fragments found in the front seat of the Presidential limousine were fired from the 6.5-millimeter Mannlicher-Carcano rifle found on the sixth floor of the Depository Building to the exclusion of all other weapons.

The three used cartridge cases found near the window on the sixth floor at the southeast corner of the building were fired from the same rifle which fired the above - described bullet and fragments, to the exclusion of all other weapons.

The windshield in the Presidential limousine was struck by a bullet fragment on the inside surface of the glass, but was not penetrated.

The nature of the bullet wounds suffered by President Kennedy and Governor Connally and the location of the car at the time of the shots establish that the bullets were fired from above and behind the Presidential limousine, striking the President and the Governor as follows:

President Kennedy was first struck by a bullet which entered at the back of his neck and exited through the lower front portion of his neck, causing a wound which would not necessarily have been lethal. The President was struck a second time by a bullet which entered the right-rear portion of his head, causing a massive and fatal wound.

Governor Connally was struck by a bullet which entered on the right side of his back and traveled downward through the right side of his chest, exiting below his right nipple. This bullet then passed through his right wrist and entered his left thigh where it caused a superficial wound.

There is no credible evidence that the shots were fired from the Triple Underpass, ahead of the motorcade, or from any other location.

(2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald. This conclusion is based upon the following:

The Mannlicher-Carcano 6.5 - millimeter Italian rifle from which the shots were fired was owned by and in the possession of Oswald.

Oswald carried this rifle into the Depository Building on the morning of November 22, 1963.

Oswald, at the time of the assassination, was present at the window from which the shots were fired.

Shortly after the assassination, the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle belonging to Oswald was found partially hidden between some cartons on the sixth floor and the improvised paper bag in which Oswald brought the rifle to the Depository was found close by the window from which the shots were fired.

Based on testimony of the experts and their analysis of films of the assassination, the Commission has concluded that a rifleman of Lee Harvey Oswald's capabilities could have fired the shots from the rifle used in the assassination within the elapsed time of the shooting. The Commission has concluded further that Oswald possessed the capability with a rifle which enabled him to commit the assassination.

Oswald lied to the police after his arrest concerning important substantive matters.

Oswald had attempted to kill Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker (Resigned, U.S. Army) on April 10, 1963, thereby demonstrating his disposition to take human life.

(5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination. This conclusion upholds the finding that Oswald fired the shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally and is supported by the following:

Two eyewitnesses saw the Tippit shooting and seven eyewitnesses heard the shots and saw the gunman leave the scene with revolver in hand. These nine eyewitnesses positively identified Lee Harvey Oswald as the man they saw.

The cartridge cases found at the scene of the shooting were fired from the revolver in the possession of Oswald at the time of his arrest to the exclusion of all other weapons.

The revolver in Oswald's possession at the time of his arrest was purchased by and belonged to Oswald.

Oswald's jacket was found along the path of flight taken by the gunman as he fled from the scene of the killing.

(6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(7) The Commission has reached the following conclusions concerning Oswald's interrogation and detention by the Dallas police:

Except for the force required to effect his arrest, Oswald was not subjected to any physical coercion by any law enforcement officials. He was advised that he could not be compelled to give any information and that any statements made by him might be used against him in court. He was advised of his right to counsel. He was given the opportunity to obtain counsel of his own choice and was offered legal assistance by the Dallas Bar Association, which he rejected at that time.

Newspaper, radio, and television reporters were allowed uninhibited access to the area through which Oswald had to pass when he was moved from his cell to the interrogation room and other sections of the building, thereby subjecting Oswald to harassment and creating chaotic conditions which were not conducive to orderly interrogation or the protection of the rights of the prisoner.

The numerous statements, sometimes erroneous, made to the press by various local law enforcement officials, during this period of confusion and disorder in the police station, would have presented serious obstacles to the obtaining of a fair trial for Oswald. To the extent that the information was erroneous or misleading, it helped to create doubts, speculations, and fears in the mind of the public which might otherwise not have arisen.

(8) The Commission has reached the following conclusions concerning the killing of Oswald by Jack Ruby on November 24, 1963:

Ruby entered the basement of the Dallas Police Department shortly after 11:17 a.m. and killed Lee Harvey Oswald at 11:21 a.m.

Although the evidence on Ruby's means of entry is not conclusive, the weight of the evidence indicates that he walked down the ramp leading from Main Street to the basement of the police department.

There is no evidence to support the rumor that Ruby may have been assisted by any members of the Dallas Police Department in the killing of Oswald.

The Dallas Police Department's decision to transfer Oswald to the county jail in full public view was unsound.

The arrangements made by the police department on Sunday morning, only a few hours before the attempted transfer, were inadequate. Of critical importance was the fact that news media representatives and others were not excluded from the basement even after the police were notified of threats to Oswald's life. These deficiencies contributed to the death of Lee Harvey Oswald.

(9) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy. The reasons for this conclusion are:

The Commission has found no evidence that anyone assisted Oswald in planning or carrying out the assassination. In this connection it has thoroughly investigated, among other factors, the circumstances surrounding the planning of the motorcade route through Dallas, the hiring of Oswald by the Texas School Book Depository Co. on October 15, 1963, the method by which the rifle was brought into the building, the placing of cartons of books at the window, Oswald's escape from the building, and the testimony of eyewitnesses to the shooting.

The Commission has found no evidence that Oswald was involved with any person or group in a conspiracy to assassinate the President, although it has thoroughly investigated, in addition to other possible leads, all facets of Oswald's associations, finances, and personal habits, particularly during the period following his return from the Soviet Union in June 1962.

The Commission has found no evidence to show that Oswald was employed, persuaded, or encouraged by any foreign government to assassinate President Kennedy or that he was an agent of any foreign government, although the Commission has reviewed the circumstances surrounding Oswald's defection to the Soviet Union, his life there from October of 1959 to June of 1962 so far as it can be reconstructed, his known contacts with the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and his visits to the Cuban and Soviet Embassies in Mexico City during his trip to Mexico from September 26 to October 3, 1963, and his known contacts with the Soviet Embassy in the United States.

The Commission has explored all attempts of Oswald to identify himself with various political groups, including the Communist Party, U.S.A., the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, and the Socialist Workers Party, and has been unable to find any evidence that the contacts which he initiated were related to Oswald's subsequent assassination of the President.

All of the evidence before the Commission established that there was nothing to support the speculation that Oswald was an agent, employee, or informant of the FBI, the CIA, or any other governmental agency. It has thoroughly investigated Oswald's relationships prior to the assassination with all agencies of the U.S. Government. All contacts with Oswald by any of these agencies were made in the regular exercise of their different responsibilities.

No direct or indirect relationship between Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby has been discovered by the Commission, nor has it been able to find any credible evidence that either knew the other, although a thorough investigation was made of the many rumors and speculations of such a relationship.

The Commission has found no evidence that Jack Ruby acted with any other person in the killing of Lee Harvey Oswald.

After careful investigation the Commission has found no credible evidence either that Ruby and Officer Tippit, who was killed by Oswald, knew each other or that Oswald and Tippit knew each other. Because of the difficulty of proving negatives to a certainty the possibility of others being involved with either Oswald or Ruby cannot be established categorically, but if there is any such evidence it has been beyond the reach of all the investigative agencies and resources of the United States and has not come to the attention of this Commission.

(10) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the U.S. Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(11) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone. Therefore, to determine the motives for the assassination of President Kennedy, one must look to the assassin himself. Clues to Oswald's motives can be found in his family history, his education or lack of it, his acts, his writings, and the recollections of those who had close contacts with him throughout his life. The Commission has presented with this report all of the background information bearing on motivation which it could discover. Thus, others may study Lee Oswald's life and arrive at their own conclusions as to his possible motives. The Commission could not make any definitive determination of Oswald's motives. It has endeavored to isolate factors which contributed to his character and which might have influenced his decision to assassinate President Kennedy. These factors were:

His deep-rooted resentment of all authority which was expressed in a hostility toward every society in which he lived;

His inability to enter into meaningful relationships with people, and a continuous pattern of rejecting his environment in favor of new surroundings;

His urge to try to find a place in history and despair at times over failures in his various undertakings;

His capacity for violence as evidenced by his attempt to kill General Walker;

His avowed commitment to Marxism and communism, as he understood the terms and developed his own interpretation of them; this was expressed by his antagonism toward the United States, by his defection to the Soviet Union, by his failure to be reconciled with life in the United States even after his disenchantment with the Soviet Union, and by his efforts, though frustrated, to go to Cuba. Each of these contributed to his capacity to risk all in cruel and irresponsible actions.

(12) The Commission recognizes that the varied responsibilities of the President require that he make frequent trips to all parts of the United States and abroad. Consistent with their high responsibilities Presidents can never be protected from every potential threat. The Secret Service's difficulty in meeting its protective responsibility varies with the activities and the nature of the occupant of the Office of President and his willingness to conform to plans for his safety. In appraising the performance of the Secret Service it should be understood that it has to do its work within such limitations. Nevertheless, the Commission believes that recommendations for improvements in Presidential protection are compelled by the facts disclosed in this investigation.

The complexities of the Presidency have increased so rapidly in recent years that the Secret Service has not been able to develop or to secure adequate resources of personnel and facilities to fulfill its important assignment. This situation should be promptly remedied.

The Commission has concluded that the criteria and procedures of the Secret Service designed to identify and protect against persons considered threats to the president were not adequate prior to the assassination.

The Protective Research Section of the Secret Service, which is responsible for its preventive work, lacked sufficient trained personnel and the mechanical and technical assistance needed to fulfill its responsibility.

Prior to the assassination the Secret Service's criteria dealt with direct threats against the President. Although the Secret Service treated the direct threats against the President adequately, it failed to recognize the necessity of identifying other potential sources of danger to his security. The Secret Service did not develop adequate and specific criteria defining those persons or groups who might present a danger to the President. In effect, the Secret Service largely relied upon other Federal or State agencies to supply the information necessary for it to fulfill its preventive responsibilities, although it did ask for information about direct threats to the President.

The Commission has concluded that there was insufficient liaison and coordination of information between the Secret Service and other Federal agencies necessarily concerned with Presidential protection. Although the FBI, in the normal exercise of its responsibility, had secured considerable information about Lee Harvey Oswald, it had no official responsibility, under the Secret Service criteria existing at the time of the President's trip to Dallas, to refer to the Secret Service the information it had about Oswald. The Commission has concluded, however, that the FBI took an unduly restrictive view of its role in preventive intelligence work prior to the assassination. A more carefully coordinated treatment of the Oswald case by the FBI might well have resulted in bringing Oswald's activities to the attention of the Secret Service.

The Commission has concluded that some of the advance preparations in Dallas made by the Secret Service, such as the detailed security measures taken at Love Field and the Trade Mart, were thorough and well executed. In other respects, however, the Commission has concluded that the advance preparations for the President's trip were deficient.

Although the Secret Service is compelled to rely to a great extent on local law enforcement officials, its procedures at the time of the Dallas trip did not call for well-defined instructions as to the respective responsibilities of the police officials and others assisting in the protection of the President.

The procedures relied upon by the Secret Service for detecting the presence of an assassin located in a building along a motorcade route were inadequate. At the time of the trip to Dallas, the Secret Service as a matter of practice did not investigate, or cause to be checked, any building located along the motorcade route to be taken by the President. The responsibility for observing windows in these buildings during the motorcade was divided between local police personnel stationed on the streets to regulate crowds and Secret Service agents riding in the motorcade. Based on its investigation the Commission has concluded that these arrangements during the trip to Dallas were clearly not sufficient.

The configuration of the Presidential car and the seating arrangements of the Secret Service agents in the car did not afford the Secret Service agents the opportunity they should have had to be of immediate assistance to the President at the first sign of danger.

Within these limitations, however, the Commission finds that the agents most immediately responsible for the President's safety reacted promptly at the time the shots were fired from the Texas School Book Depository Building.