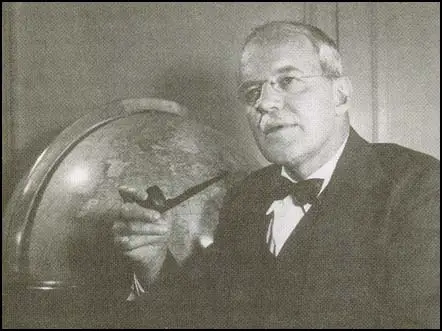

Allen Dulles

Allen Dulles, the son of a Presbyterian minister, and the younger brother of John Foster Dulles, was born in Watertown on 7th April 1893. His grandfather was John Watson Foster, Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison. His uncle, Robert Lansing, was Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President Woodrow Wilson.

After attending Princeton University he joined the diplomatic service and served in Vienna, Berne, Paris, Berlin and Instanbul. In 1921 he exposed the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion as a forgery, providing the story to The Times and The New York Times. In 1922 he was appointed as chief of Division of Near Eastern Affairs.

Dulles returned to the United States and in 1926 he obtained a law degree from George Washington University Law School and took a job at the New York City company, Sullivan and Cromwell, where his brother, John Foster Dulles, was a partner. He became a director of the Council on Foreign Relations in 1927 and became its secretary in 1933. He also served as an adviser to the delegation on arms limitation at the League of Nations. There he had the opportunity to meet with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

In 1935 Dulles visited Nazi Germany. He was appalled by the treatment of German Jews and advocated his law firm to close their Berlin office. Dulles also joined forces with Hamilton Fish Armstrong to produce two books, Can We Be Neutral? (1936) and Can America Stay Neutral? (1939). Dulles was recruited by the British Security Coordination in 1940. In July 1941 Sydney Morrell was asked to write a report on the organisations that had been set up with the help of the BSC to call for intervention in the Second World War. It included reference to the help provided by Dulles.

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in July 1942. The OSS replaced the former American intelligence system, Office of the Coordinator of Information (OCI) that was considered to be ineffective. Roosevelt selected Colonel William Donovan as the first director of the organization, who had spent some time studying the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an organization set up by the British government in July 1940. Allen Dulles was recruited to run the New York City office. His address was Room 3603, 630 Fifth Avenue. The address of British Security Coordination was Room 3603, 630 Fifth Avenue.

Other key figures in the OSS was George K. Bowen, the head of Special Activities, David Bruce (head of intelligence) and William Lane Rehm (head of finance). Donald Chase Downes, who had been working for William Stephenson, the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC), applied to join the OSS. He later recalled in his autobiography, The Scarlett Thread (1953): "I was asked for references and for my life story and a week later was invited to Allen Dulles' new office. It was in Rockefeller Plaza, just a floor over the BSC secret office... At first Dulles and his aides were, quite justifiably, afraid of me - I had been an agent of a foreign power when that was prohibited by the Neutrality Act. So I was to work out of my own office in another part of New York."

Downes worked with Arthur Goldberg on the Labor Desk. "We were a fortunate combination, able to work together at high speed without friction. Our ideas, our plans, our points of view almost perfectly meshed; our abilities were peculiarly supplementary; our work so mutually understood and developed that each was able at any time to carry on or make a decision for the others." They recruited refugee German trade union leaders who had fled from Nazi Germany. Downes pointed out that Dulles believed in "an alliance between extreme right and extreme left" to remove Adolf Hitler from power.

Dulles was transferred to Berne and became Swiss Director of the Office of Strategic Services. He used this neutral country to obtain important information on Nazi Germany. Dulles also developed contacts with anti-Hitler figures in Germany including Klaus von Stauffenberg, Arthur Nebe, Julius Leber, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, Helmuth von Moltke, Wilhelm Leuschner, Ulrich von Hassell, Ludwig Beck, Carl Friederich Goerdeler, and Wilhelm Leuschner. However, he was refused permission to give full support to the July Plot in 1944.

As soon as the Second World War ended President Harry S. Truman ordered the Office of Strategic Services to be closed down. However, it provided a model for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that was established in September 1947. Dulles joined the CIA and became deputy director of the organization.

After the war a small group of people began meeting on a regular basis. The group, living in Washington, became known as the Georgetown Set or the Wisner Gang. At the first the key members of the group were former members of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). This included Frank Wisner, Philip Graham, David Bruce, Tom Braden, Stewart Alsop and Walt Rostow. Over the next few years others like Allen Dulles, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Richard Bissell, Joseph Alsop, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen, Desmond FitzGerald, Tracy Barnes, Cord Meyer, James Angleton, William Averill Harriman, John McCloy, Felix Frankfurter, John Sherman Cooper, James Reston, and Paul Nitze joined their regular parties. Some like Bruce, Braden, Bohlen, McCloy, Meyer and Harriman spent a lot of their time working in other countries. However, they would always attend these parties when in Georgetown.

Tommy Corcoran worked as a paid lobbyist for Sam Zemurray and the United Fruit Company. Zemurray became concerned that Captain Jacobo Arbenz, one of the heroes of the 1944 revolution, would be elected as the new president of Guatemala. In the spring of 1950, Corcoran went to see Thomas C. Mann, the director of the State Department’s Office of Inter-American Affairs. Corcoran asked Mann if he had any plans to prevent Arbenz from being elected. Mann replied: “That is for the people of that country to decide.”

Unhappy with this reply, Corcoran paid a call on Allen Dulles, who represented United Fruit in the 1930s, was far more interested in Corcoran’s ideas. “During their meeting Dulles explained to Corcoran that while the CIA was sympathetic to United Fruit, he could not authorize any assistance without the support of the State Department. Dulles assured Corcoran, however, that whoever was elected as the next president of Guatemala would not be allowed to nationalize the operations of United Fruit.”

In 1954 Dulles, now director of the CIA organized PB/SUCCESS, a CIA operation to overthrow President Jacobo Arbenz. Other CIA officers involved in this operation included David Atlee Phillips, Tracy Barnes, William (Rip) Robertson and E. Howard Hunt. Hecksher's role was to supply front-line reports and to bribe Arbenz's military commanders. It was later discovered that one commander accepted $60,000 to surrender his troops. Ernesto Guevara attempted to organize some civil militias but senior army officers blocked the distribution of weapons.

With the help of President Anastasio Somoza, Colonel Carlos Castillo had formed a rebel army in Nicaragua. It has been estimated that between January and June, 1954, the CIA spent about $20 million on Castillo's army. Jacobo Arbenz now believed he stood little chance of preventing Castillo gaining power. Accepting that further resistance would only bring more deaths he announced his resignation.

According to David Atlee Phillips (Night Watch), President Dwight Eisenhower was so pleased with the overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz he invited Allen Dulles, Henry Hecksher, Tracy Barnes, David Sanchez Morales, and Allen Dulles to a personal debriefing at the White House.

In March 1960 Richard Bissell had drafted a top-secret policy paper entitled: A Program of Covert Action Against the Castro Regime (code-named JMARC). This paper was based on PBSUCCESS, the policy that had worked so well in Guatemala in 1954. In fact, Bissell assembled the same team as the one used in Guatemala (Tracy Barnes, David Atlee Phillips, David Morales, Jake Esterline, Rip Robertson, E. Howard Hunt and Gerry Droller “Frank Bender”). The only one missing was Frank Wisner, who had suffered a mental breakdown in 1956. Added to the team was Desmond FitzGerald, William Harvey and Ted Shackley.

The policy involved the creation of an exile government, a powerful propaganda offensive, developing a resistance group within Cuba and the establishment of a paramilitary force outside Cuba. In Guatemala this strategy involved persuading Jacobo Arbenz to resign. Richard Bissell knew of course that Fidel Castro would never agree to that. Therefore, Castro had to be removed just before the invasion took place. If this did not happen, the plan would not work. In August 1960 Dwight Eisenhower authorized $13m to pay for JMARC.

Sidney Gottlieb of the CIA Technical Services Division was asked to come up with proposals that would undermine Castro's popularity with the Cuban people. Plans included a scheme to spray a television studio in which he was about to appear with an hallucinogenic drug and contaminating his shoes with thallium which they believed would cause the hair in his beard to fall out.

These schemes were rejected and instead Bissell decided to arrange the assassination of Fidel Castro. In September 1960 Richard Bissell and Allen W. Dulles, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro.

Robert Maheu, a veteran of CIA counter-espionage activities, was instructed to offer the Mafia $150,000 to kill Fidel Castro. The advantage of employing the Mafia for this work is that it provided CIA with a credible cover story. The Mafia were known to be angry with Castro for closing down their profitable brothels and casinos in Cuba. If the assassins were killed or captured the media would accept that the Mafia were working on their own.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had to be brought into this plan as part of the deal involved protection against investigations against the Mafia in the United States. Castro was later to complain that there were twenty ClA-sponsered attempts on his life. Eventually Johnny Roselli and his friends became convinced that the Cuban revolution could not be reversed by simply removing its leader. However, they continued to play along with this CIA plot in order to prevent them being prosecuted for criminal offences committed in the United States.

John F. Kennedy was given a copy of the JMARC proposal by Bissell and Allen W. Dulles in Palm Beach on 18th November, 1960. According to Bissell, Kennedy remained impassive throughout the meeting. He expressed surprise only at the scale of the operation. The plan involved a 750 man landing on a beach near the port of Trinidad, on the south coast of Cuba. The CIA claimed that Trinidad was a hotbed of opposition to Castro. It was predicted that within four days the invasion force would be able to recruit enough local volunteers to double in size. Airborne troops would secure the roads leading to the town and the rebels would join up with the guerrillas in the nearby Escambray Mountains.

In March 1961 John F. Kennedy asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff to vet the JMARC project. As a result of “plausible deniability” they were not given details of the plot to kill Castro. The JCS reported that if the invaders were given four days of air cover, if the people of Trinidad joined the rebellion and if they were able to join up with the guerrillas in the Escambray Mountains, the overall rating of success was 30%. Therefore, they could not recommend that Kennedy went along with the JMARC project.

At a meeting on 11th March, 1961, Kennedy rejected Bissell’s proposed scheme. He told him to go away and draft a new plan. He asked for it to be “less spectacular” and with a more remote landing site than Trinidad. It appears that Kennedy had completely misunderstood the report from the JCS. They had only rated it as high as a 30% chance of success because it was going to involve such a large landing force and was going to take place in Trinidad, near to the Escambray Mountains. After all, Fidel Castro had an army and militia of 200,000 men.

Richard Bissell now resubmitted his plan. As requested, the landing was no longer at Trinidad. Instead he selected Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs). This was 80 miles from the Escambray Mountains. What is more, this journey to the mountains was across an impenetrable swamp. As Bissell explained to Kennedy, this means that the guerrilla fallback option had been removed from the operation.

As Dulles recorded at the time: “We felt that when the chips were down, when the crisis arose in reality, any action required for success would be authorized rather than permit the enterprise to fail.” In other words, he knew that the initial invasion would be a disaster, but believed that Kennedy would order a full-scale invasion when he realized that this was the case. According to Evan Thomas (The Very Best Men): “Some old CIA hands believe that Bissell was setting a trap to force U.S. intervention”. Edgar Applewhite, a former deputy inspector general, believed that Bissell and Dulles were “building a tar baby”. Jake Esterline was very unhappy with these developments and on 8th April attempted to resign from the CIA. Bissell convinced him to stay.

On 10th April, 1961, Bissell had a meeting with Robert Kennedy. He told Kennedy that the new plan had a two out of three chance of success. Bissell added that even if the project failed the invasion force could join the guerrillas in the Escambray Mountains. Kennedy was convinced by this scheme and applied pressure on those like Chester Bowles, Theodore Sorenson and Arthur Schlesinger who were urging John F. Kennedy to abandon the project.

On 13th April, Kennedy asked Richard Bissell how many B-26s were going to be used. He replied sixteen. Kennedy told him to use only eight. Bissell knew that the invasion could not succeed without adequate air cover. Yet he accepted this decision based on the idea that he would later change his mind “when the chips were down”. The following day B-26 planes began bombing Cuba's airfields. After the raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. Two days later five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles arrived at the Bay of Pigs.

Allen W. Dulles was in Puerto Rico during the invasion. He left Charles Cabell in charge. Instead of ordering the second air raid he checked with Dean Rusk. He contacted Kennedy who said he did not remember being told about the second raid. After discussing it with Rusk he decided to cancel it. Instead the operation tried to rely on Radio Swan, broadcasts being made on a small island in the Caribbean by David Atlee Phillips, calling for the Cuban Army to revolt. They failed to do this. Instead they called out the militia to defend the fatherland from “American mercenaries”.

At 7 a.m. on 18th April, Richard Bissell told John F. Kennedythat the invasion force was trapped on the beaches and encircled by Castro’s forces. Then Bissell asked Kennedy to send in American forces to save the men. Bissell expected him to say yes. Instead he replied that he still wanted “minimum visibility”.

After the air raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. Two days later five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles arrived at the Bay of Pigs. Two of the ships were sunk, including the ship that was carrying most of the supplies. Two of the planes that were attempting to give air-cover were also shot down.

That night Bissell had another meeting with John F. Kennedy. This time it took place in the White House and included General Lyman Lemnitzer, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Admiral Arleigh Burke, Chief of Naval Operations. Bissell told Kennedy that the operation could still be saved if American warplanes were allowed to fly cover. Admiral Burke supported him on this. General Lemnitzer called for the Brigade to join the guerrillas in the Escambray Mountains. Bissell explained this was not an option as their route was being blocked by 20,000 Cuban troops.

Within seventy-two hours all the invading troops had been killed, wounded or had surrendered. Bissell had a meeting with John F. Kennedy about the Bay of Pigs operation. Kennedy admitted it was his fault that the operation had been a disaster. Kennedy added: "In a parliamentary government, I'd have to resign. But in this government I can't, so you and Allen (Dulles) have to go."

As Evan Thomas points out in The Very Best Men: "Bissell had been caught in his own web. "Plausible deniability" was intended to protect the president, but as he had used it, it was a tool to gain and maintain control over an operation... Without plausible deniability, the Cuba project would have turned over to the Pentagon, and Bissell would have have become a supporting actor."

The CIA's internal inquiry into this fiasco and Allen W. Dulles was forced to resign as Director of the CIA (November, 1961) by President John F. Kennedy. After the death of Kennedy, his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." The seven man commission was headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and included Allen W. Dulles, Gerald Ford, John J. McCloy, Richard B. Russell, John S. Cooper and Thomas H. Boggs.

Lyndon B. Johnson also commissioned a report on the assassination from J. Edgar Hoover. Two weeks later the Federal Bureau of Investigation produced a 500 page report claiming that Lee Harvey Oswald was the sole assassin and that there was no evidence of a conspiracy. The report was then passed to the Warren Commission. Rather than conduct its own independent investigation, the commission relied almost entirely on the FBI report.

The Warren Commission was published in October, 1964. It reached the following conclusions:

(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

(2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

(5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

(6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(7) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

(8) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the U.S. Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(9) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone.

Dulles published several books including The German Underground, The Craft of Intelligence and Great True Spy Stories.

Allen Dulles died of cancer in 1969.

Primary Sources

(1) David Atlee Phillips, The Night Watch: 25 Years of Peculiar Service (1977)

"Tomorrow morning, gentlemen," Dulles said, "we will go to the White House to brief the President. Let's run over your presentations." It was a warm summer night. We drank iced tea as we sat around a garden table in Dulles' back yard. The lighted shaft of the Washington Monument could be seen through the trees. . . . Finally Brad (Colonel Albert Haney) rehearsed his speech. When he finished Alien Dulles said, "Brad, I've never heard such crap." It was the nearest thing to an expletive I ever heard Dulles use. The Director turned to me "They tell me you know how to write. Work out a new speech for Brad...

We went to the White House in the morning. Gathered in the theater in the East Wing were more notables than I had ever seen: the President, his Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Secretary of State - Alien Dulles's brother, Foster - the Attorney General, and perhaps two dozen other members of the President's Cabinet and household staff....

The lights were turned off while Brad used slides during his report. A door opened near me. In the darkness I could see only a silhouette of the person entering the room; when the door closed it was dark again, and I could not make out the features of the man standing next to me. He whispered a number of questions: "Who is that? Who made that decision?"

I was vaguely uncomfortable. The questions from the unknown man next to me were very insistent, furtive. Brad finished and the lights went up. The man moved away. He was Richard Nixon, the Vice President.

Eisenhower's first question was to Hector (Rip Robertson): "How many men did Castillo Armas lose?" Hector (Rip Robertson) said only one, a courier... . Eisenhower shook his head, perhaps thinking of the thousands who had died in France. "Incredible..."

Nixon asked a number of questions, concise and to the point, and demonstrated a thorough knowledge of the Guatemalan political situation. He was impressive - not at all the disturbing man he was in the shadows.

Eisenhower turned to his Chief of the Joint Chiefs. "What about the Russians? Any reaction?"

General Ridgeway answered. "They don't seem to be up to anything. But the navy is watching a Soviet sub in the area; it could be there to evacuate some of Arbenz's friends, or to supply arms to any resisters."

Eisenhower shook hands all around. "Great," he said to Brad, "that was a good briefing." Hector and I smiled at each other as Brad flushed with pleasure. The President's final handshake was with Alien Dulles. "Thanks Allen, and thanks to all of you. You've averted a Soviet beachhead in our hemisphere." Eisenhower spoke to his Chief of Naval Operations "Watch that sub. Admiral. If it gets near the coast of Guatemala we'll sink the son-of-a-bitch. ' The President strode from the room.

(2) David McKean, Peddling Influence (2004)

As planning for the U.S. plot progressed, Corcoran and other top officials at United Fruit became anxious about identifying a future leader who would establish favorable relations between the government and the company. Secretary of State Dulles moved to add a "civilian" adviser to the State Department team to help expedite Operation Success. Dulles chose a friend of Corcoran's, William Pawley, a Miami-based millionaire who, along with Corcoran, Chennault, and Willauer, had helped set up the Flying Tigers in the early r94os and then helped several years later to transform it into the CIA's airline, Civil Air Transport. Besides his association with Corcoran, Pawley's most important qualification for the job was that he had a long history of association with right-wing Latin American dictators.

CIA director Dulles had grown disillusioned with J. C. King and asked Colonel Albert Haney, the CIA station chief in Korea, to be the U.S. field commander for the operation. Haney enthusiastically accepted, although he was apparently unaware of the role that the United Fruit Company had played in his selection. Haney had been a colleague of King's, and though King was no longer directing the operation, he remained a member of the agency planning team. He suggested that Haney meet with Tom Corcoran to see about arming the insurgency force with the weapons that had been mothballed in a New York warehouse after the failed Operation Fortune. When the supremely confident Haney said he didn't need any help from a Washington lawyer, King rebuked him, "If you think you can run this operation without United Fruit, you're crazy!"

The close working relationship between the CIA and United Fruit was perhaps best epitomized by Allen Dulles's encouragement to the company to help select an expedition commander for the planned invasion. After the CIA's first choice was vetoed by the State Department, United Fruit proposed Corcova Cerna, a Guatemalan lawyer and coffee grower. Cerna had long worked for the company as a paid legal adviser, and even though Corcoran referred to him as "a liberal," he believed that Cerna would not interfere with the company's land holdings and operations. After Cerna was hospitalized with throat cancer, a third candidate, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, emerged as the compromise choice.

According to United Fruit's Thomas McCann, when the Central Intelligence Agency finally launched Operation Success in late June 1954, "United Fruit was involved at every level." From neighboring Honduras, Ambassador Willauer, Corcoran's former business partner, directed bombing raids on Guatemala City. McCann was told that the CIA even shipped down the weapons used in the uprising "in United Fruit boats."

On June 27, 1954, Colonel Armas Ousted the Arbenz government and ordered the arrest of all communist leaders in Guatemala. While the coup was successful, a dark chapter was opened in American support for right wing military dictators in Central America.

(3) David Wise and Thomas Ross, Invisible Government (1964)

The CIA is, of course, the biggest, most important and most influential branch of the Invisible Government. The agency is organized into four divisions: Intelligence, Plans, Research, Support, each headed by a deputy director.

The Support Division is the administrative arm of the CIA. It is in charge of equipment, logistics, security and communications. It devises the CIA's special codes, which cannot be read by other branches of the government.

The Research Division is in charge of technical intelligence. It provides expert assessments of foreign advances in science, technology and atomic weapons. It was responsible for analyzing the U-2 photographs brought back from the Soviet Union between 1956 and 1960. And it has continued to analyze subsequent U-2 and spy-satellite pictures. In this it works with the CIA in running the National Photo Intelligence Center.

Herbert "Pete" Scoville, who headed the Research Division for eight years, left in August of 1963 to become an assistant director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. He was replaced as the CIA's deputy director for research by Dr. Albert D. Wheelon.

The Plans Division is in charge of the CIA's cloak-and-dagger activities. It controls all foreign special operations, such as Guatemala and the Bay of Pigs, and it collects all of the agency's covert intelligence through spies and informers overseas.

Allen Dulles was the first deputy director for plans. He was succeeded as DDP by Frank Wisner, who was replaced in i958 by Bissell, who, in turn, was succeeded in 1962 by his deputy, Richard Helms.

A native of St. David's, Pennsylvania, Helms studied in Switzerland and Germany and was graduated from Williams College in 1935. He worked for the United Press and the Indianapolis Times, and then, during World War II, he served as a lieutenant commander in the Navy attached to the OSS. When the war ended and some OSS men were transferred to the CIA, he stayed on and rose through the ranks.

(4) Joseph Trento, Secret History of the CIA (2001)

The Kronthal case demonstrated just how careless Dulles and Wisner were about their early recruitments. As the CIA investigators later found, Kronthal had led a dark life in the art world, working with the Nazi regime during the war in fencing art stolen from Jews. It was during this period that German intelligence caught him in a homosexual act with an underage German boy. However, his friendship with Herman Goering prevented his arrest and saved him from scandal. Kronthal had every reason to believe the incident had been safely covered up.

When the Soviets took Berlin, they found all of Goering's private files, which included Kronthal's records. When Kronthal replaced Dulles as Bern Station Chief in 1945, the NKVD prepared a honey trap based on the information they had obtained. Chinese boys were imported and made available to him, and he was successfully filmed in the act. "His recruitment was the most well-kept secret in the history of the Agency," James Angleton said. The entire time Kronthal worked for Dulles and Wisner, he was reporting every detail back to Moscow Center. Kronthal was the first mole in the CIA. He served the Soviets for more than five years.

(5) Harold Weisberg, Whitewash: The Report on the Warren Report (1966)

There is in neither the Commission's Report nor in any of the 26 printed volumes of its hearings and exhibits any sign that the Commission considered this assassination as a political crime, an unvarying characteristic of all assassinations. Likewise, despite the great amount of space devoted to the subject of conspiracy, there is no sign of any real quest for evidence of conspiracy in the broad or political sense. Both the FBI and the Commission decided, as had the police before them, that Oswald was their legitimate prey. Nowhere in the Report is there any evidence that any other assassin or assassins were ever sought or considered. Can anything be logically concluded other than that nobody wanted to find a different assassin or any additional assassin?

Yet there were abundant and obvious indications of both suspicion of a conspiracy and of its existence. The Report was able to avoid them, a task made easier by the nature of the hearings. It was as successful in avoiding both the obvious indications and the even more obvious suspicions, some of which are dealt with in this book.

The superficial and immature manner in which the Report deals with the possibility of a conspiracy or of a different assassin is only one of the ways in which the Commission may have crippled itself. Despite references in both the Report and the press to the Commission's investigators, the fact is that, in the accepted sense, the Commission had no investigators of its own. It drew upon the men available in the Executive Branch, chiefly the FBI and Secret Service, who were not employees of the Commission and whose primary responsibilities were to those who did employ them.

While there is no suggestion that these agencies were in any way involved m the assassination, they were, nonetheless, subject to Commission criticism and they were, in fact, so criticized. In addition, the Secret Service was directly responsible for the President's welfare and safety, and he was killed while they were protecting him. Besides its normal duty of aiding the Secret Service, the FBI had Oswald under surveillance or investigation at the time the President was killed. He was what might be called an "active" case.

Therefore, both agencies and their employees had personal involvements in the investigation that amounted to conflicts of interest. On one hand was the need for a complete, impartial and exhaustive investigation regardless of where it led and what it showed. On the other, the reputations of the agencies and their employees could have been at stake, for any error, no matter how innocent, could have made the Dallas tragedy possible. This situation was unfair to the agencies, which did not create it, and could have burdened them with impermissible conflicts and temptations, no matter how unconsciously. Further, the Dallas representatives of these agencies had ties of friendship and sometimes long association with the local police and, when the investigation of the assassination was over, faced the need for continuing, day-to-day working associations with them. Contemporarily and historically, it would have been better if the Commission had had its own staff of investigators in the field and had restricted its use of the FBI and Secret Service to technical services.