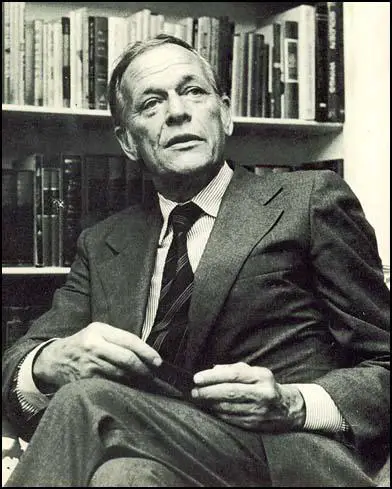

Thomas Braden

Thomas Wardell Braden, the son of an insurance agent was born in Greene, Iowa, on 22nd February, 1917. Braden graduated in Political Science from Dartmouth College in 1940. He got so excited by the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the British Army. He was assigned to the 8th Army, 7th Armoured Division and saw action in North Africa and Italy.

Braden was recruited into Special Operations Executive (SOE) and in 1944, along with Stewart Alsop he went to work with Allen Dulles at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). In an interview he gave to John Ranelagh (The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA), Braden admits that in 1944 he introduced Kim Philby to Dulles. After the war Braden co-wrote with Alsop a history of the OSS called Sub Rosa: The O.S.S. and American Espionage (1946).

Braden moved to Washington where he associated with a group of journalists, politicians and government officials that became known as the Georgetown Set. This included Frank Wisner, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Richard Bissell, Desmond FitzGerald, Joseph Alsop, Stewart Alsop, Tracy Barnes, Philip Graham, David Bruce, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen, Cord Meyer, Richard Helms, Desmond FitzGerald, Frank Wisner, James Angleton, William Averill Harriman, John McCloy, Felix Frankfurter, John Sherman Cooper, James Reston, Allen W. Dulles and Paul Nitze. Most men brought their wives to these gatherings. Members of what was later called the Georgetown Ladies' Social Club included Katharine Graham, Mary Pinchot Meyer, Sally Reston, Polly Wisner, Joan Braden, Lorraine Cooper, Evangeline Bruce, Avis Bohlen, Janet Barnes, Tish Alsop, Cynthia Helms, Marietta FitzGerald, Phyllis Nitze and Annie Bissell.

Allen Dulles joined the CIA as Deputy Director of Operations in December 1950 and he brought in Braden as his assistant. As Frances Stonor Saunders points out in Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999): "Allen Dulles joined the CIA in December 1950 as Deputy Director of Operations. This was a position of immense scope, giving Dulles responsibility for collecting intelligence, and for supervising Frank Wisner's division, the Office of Policy Coordination. One of his first acts was to recruit Tom Braden, one of his most dashing OSS officers, a man who had cultivated many high-level contacts since his return to civilian life. Wiry, sandy-haired, and with a craggy, handsome visage, Braden looked like a composite of John Wayne, Gary Cooper and Frank Sinatra."

Assigned the codename "Homer D. Hoskins", Braden was initially without portfolio, nominally assigned to Frank Wisner and the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), but in reality working directly for Dulles. He was given responsibility for studying Soviet propaganda. He reported: "If the other side can use ideas that are camouflaged as being local rather than Soviet supported or stimulated, then we ought to be able to use ideas camouflaged as local ideas".

Braden suggested to Allen Dulles that he should be allowed to establish International Organizations Division (IOD) to counteract Soviet propaganda. Dulles agreed and Cord Meyer was appointed as his deputy. The IOD helped established anti-Communist front groups in Western Europe. The IOD was dedicated to infiltrating academic, trade and political associations. The objective was to control potential radicals and to steer them to the right. Braden later claimed that such measures were necessary in the early 1950s because the Soviet Union operated "immensely powerful" front groups in Europe.

Braden oversaw the funding of groups such as the National Student Association, the Congress of Cultural Freedom, Communications Workers of America, the American Newspaper Guild and the National Educational Association. According to Braden, the CIA was putting around $900,000 a year into the Congress of Cultural Freedom. Some of this money was used to publish its journal, Encounter.

Braden and the IOD also worked closely with anti-Communist leaders of the trade union movement such as George Meany of the Congress for Industrial Organization and the American Federation of Labor. This was used to fight Communism inits own ranks. As Braden said: "The CIA could do exactly as it pleased. It could buy armies. It could buy bombs. It was one of the first worldwide multinationals."

The policy of funding non-communist organisations got the IOD into trouble in 1952. Joseph McCarthy discovered what was happening but according to Roy Cohn, one of his aides, he considered the CIA as granting large subsidies to pro-Communist organisations". Frances Stonor Saunders has argued that "this was a critical moment: McCarthy's unofficial anti-Communism was on the verge of disrupting, perhaps sinking, the CIA's most elaborate and effective network of Non-Communist Left fronts." As Kai Bird has pointed out: "A lot of these covert operations ironically were placed at risk because of McCarthy, who threatened at one point to blow their cover because, from his perspective, this was an American agency, the CIA, going into cahoots with lefties."

In November, 1954, Braden left the CIA. Cord Meyer replaced him as head of International Organizations Division. Braden became the new owner of the newspaper, The Blade Tribune in California. He also became a popular newspaper columnist and worked as a political commentator on radio and television. Braden's wife, Joan Braden, as well as being the mother of eight children was a public relations executive, magazine writer, television interviewer and an aide to John F. Kennedy.

According to Warren Hinckle and William Turner (Deadly Secrets), in 1963 Braden advised Robert Kennedy: "Why don't you just go on a crusade to find out about the murder of your brother?". Kennedy shook his head and said it was too horrible to think about and that he decided to just accept the findings of the Warren Commission.

At the end of 1966, Desmond FitzGerald, Directorate for Plans, discovered that Ramparts, a left-wing publication, were planning to publish an article that the International Organizations Division had been secretly funding the National Student Association. FitzGerald ordered Edgar Applewhite to organize a campaign against the magazine. Applewhite later told Evan Thomas for his book, The Very Best Men: "I had all sorts of dirty tricks to hurt their circulation and financing. The people running Ramparts were vulnerable to blackmail. We had awful things in mind, some of which we carried off." This dirty tricks campaign failed to stop the magazine publishing this story in March, 1967. The article, written by Sol Stern, was entitled NSA and the CIA. As well as reporting CIA funding of the National Student Association it exposed the whole system of anti-Communist front organizations in Europe, Asia, and South America.

Stewart Alsop, phoned up Braden and asked him to write an article for the Saturday Evening Post in response to what Stern had written. The article, entitled, I'm Glad the CIA is Immoral , appeared on 20th May 1967. Braden defended the activities of the International Organizations Division unit of the CIA. Braden admitted that for more than 10 years, the CIA had subsidized Encounter through the Congress for Cultural Freedom - which it also funded - and that one of its staff was a CIA agent.

According to Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999): "The effect of Braden's article was to sink the CIA's covert association with the Non-Communist Left once and for all." Another CIA agent, John Hunt, pointed out: "Tom Braden was a company man... if he was really acting independently, would have had much to fear. My belief is that he was an instrument down the line somewhere of those who wanted to get rid of the NCL (Non-Communist Left). Don't look for a lone gunman - that's mad, just as it is with the Kennedy assassination... I do believe there was an operational decision to blow the Congress and the other programs out of the water."

Braden also confessed that the activities of the CIA had to be kept secret from Congress. As he pointed out in the article: "In the early 1950s, when the cold war was really hot, the idea that Congress would have approved many of our projects was about as likely as the John Birch Society's approving Medicare."

On 5th April, 1975, Tom Braden published an article, What's Wrong with the CIA? in The Saturday Review. Braden argued: "Power, arrogance, and the inside-outside syndrome are what's wrong with the CIA, and to some extent, the faults are occupational and even necessary tools for the job. But the events of the Cold War and the coincidence of Allen Dulles' having such enormous discretionary powers enlarged occupational risks until they became faults, and the faults created a monstrosity. The inside-outside syndrome withheld the truth from Adlai Stevenson so that he was forced to make a spectacle of himself on the floor of the United Nations by denying that the United States had anything to do with the invasion of Cuba. The same syndrome has made a sad and worried man of Richard Helms. It's a shame what happened to the CIA. It could have consisted of a few hundred scholars to analyze intelligence, a few hundred spies in key positions, and a few hundred operators ready to carry out rare tasks of derring-do. Instead, it became a gargantnan monster, owning properly all over the world, running airplanes and newspapers and radio stations and banks and armies and navies, offering temptation to successive Secretaries of State, and giving at least one President a brilliant idea; Since the machinery for deceit existed, why not use it?"

Two months later Tom Braden gave a television interview to the UK television program, World in Action: The Rise and Fall of the CIA. It included the following: "If the director of CIA wanted to extend a present, say, to someone in Europe - a Labour leader - suppose he just thought, This man can use fifty thousand dollars, he's working well and doing a good job - he could hand it to him and never have to account to anybody... Journalists were a target, labor unions a particular target - that was one of the activities in which the communists spent the most money."

In 1975 Braden published the autobiographical novel, Eight is Enough. The book is about a newspaper columnist, his wife and their eight children. The book was adapted into the TV series of the same name which ran 1977 to 1981.

Braden also co-hosted the Buchanan-Braden Program, a three-hour daily radio show with conservative Patrick Buchanan, and delivered daily commentary on the NBC radio network from 1978 to 1984. Later he also worked with Buchanan on the CNN program Crossfire.

Although Braden's role in the programs was promoted as representing the political left, some critics have questioned this label. Media critic Jeff Cohen argued in I'm Not a Leftist, But I Play One on TV: "Take Crossfire, started by CNN in 1982 as the only nightly forum on national TV purporting to offer an ideological battle between co-hosts of left and right. Crossfire's co-host "on the left" for the first seven years was a haplessly ineffectual centrist, Tom Braden, a guy who makes Alan Colmes look like an ultraleft firebrand. In CNN's eyes, Braden apparently earned his leftist credentials by having been a high-level CIA official - ironically enough, in charge of covert operations against the political left of Western Europe." Timothy Leary told a reporter that watching Crossfire was like "watching the left wing of the CIA debating the right wing of the CIA". Braden left the show in 1989.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Braden, Saturday Evening Post (20th May, 1967)

On the desk in front of me as I write these lines is a creased and faded yellow paper. It bears the following inscription in pencil: "Received from Warren G. Haskins, $15,000. (signed) Norris A. Grambo."

I went in search of this paper on the day the newspapers disclosed the "scandal" of the Central Intelligence Agency's connections with American students and labor leaders. It was a wistful search, and when it ended, I found myself feeling sad.

For I was Warren G. Haskins. Norris A. Grambo was Irving Brown, of the American Federation of Labor. The $15,000 was from the vaults of the CIA, and the piece of yellow paper is the last memento I possess of a vast and secret operation whose death has been brought about by small-minded and resentful men.

It was my idea to give the $15,000 to Irving Brown. He needed it to pay off his strong-arm squads in Mediterranean ports, so that American supplies could be unloaded against the opposition of Communist dock workers. It was also my idea to give cash, along with advice, to other labor leaders, to students, professors and others who could help the United States in its battle with Communist fronts.

It was my idea. For 17 years I had thought it was a good idea. Yet here it was in the newspapers, buried under excoriation. Walter Lippmann, Joseph Kraft. Editorials. Outrage. Shock.

"What's gone wrong?" I said to myself as I looked at the yellow paper. "Was there something wrong with me and the others back in 1950? Did we just think we were helping our country, when in fact we ought to have been hauled up before Walter Lippmann?

"And what's wrong with me now? For I still think it was and is a good idea, an imperative idea. Am I out of my mind? Or is it the editor of The New York Times who is talking nonsense?"

And so I sat sadly amidst the dust of old papers, and after a time I decided something. I decided that if ever I knew a truth in my life, I knew the truth of the cold war, and I knew what the Central Intelligence Agency did in the cold war, and never have I read such a concatenation of inane, misinformed twaddle as I have now been reading about the CIA.

Were the undercover payments by the CIA "immoral"? Surely it cannot be "immoral" to make certain that your country's supplies intended for delivery to friends are not burned, stolen or dumped into the sea.

Are CIA efforts to collect intelligence anywhere it can "disgraceful"? Surely it is not "disgraceful" to ask somebody whether he learned anything while he was abroad that might help his country.

People who make these charges must be naïve. Some of them must be worse. Some must be pretending to be naïve.

Take Victor Reuther, assistant to his brother Walter, president of the United Automobile Workers. According to Drew Pearson, Victor Reuther complained that the American Federation of Labor got money from the CIA and spent it with "undercover techniques." Victor Reuther ought to be ashamed of himself. At his request, I went to Detroit one morning and gave Walter $50,000 in $50 bills. Victor spent the money, mostly in West Germany, to bolster labor unions there. He tried "undercover techniques" to keep me from finding out how he spent it. But I had my own "undercover techniques." In my opinion and that of my peers in the CIA, he spent it with less than perfect wisdom, for the German unions he chose to help weren't seriously short of money and were already anti-Communist. The CIA money Victor spent would have done much more good where unions were tying up ports at the order of Communist leaders.

As for the theory advanced by the editorial writers that there ought to have been a Government foundation devoted to helping good causes agreed upon by Congress-this may seem sound, but it wouldn't work for a minute. Does anyone really think that congressmen would foster a foreign tour by an artist who has or has had left-wing connections? And imagine the scuffles that would break out as congressmen fought over money to subsidize the organizations in their home districts.

Back in the early 1950's, when the cold war was really hot, the idea that Congress would have approved many of our projects was about as likely as the John Birch Society's approving Medicare. I remember, for example, the time I tried to bring my old friend, Paul-Henri Spaak of Belgium, to the U.S. to help out in one of the CIA operations.

Paul-Henri Spaak was and is a very wise man. He had served his country as foreign minister and premier. CIA Director Allen Dulles mentioned Spaak's projected journey to the then Senate Majority Leader William F. Knowland of California. I believe that Mr. Dulles thought the senator would like to meet Mr. Spaak. I am sure he was not prepared for Knowland's reaction:

"Why," the senator said, "the man's a socialist."

"Yes," Mr. Dulles replied, "and the head of his party. But you don't know Europe the way I do, Bill. In many European countries, a socialist is roughly equivalent to a Republican." Knowland replied, "I don't care. We aren't going to bring any socialists over here."

The fact, of course, is that in much of Europe in the 1950's, socialists, people who called themselves "left"-the very people whom many Americans thought no better than Communists-were the only people who gave a damn about fighting Communism.

But let us begin at the beginning.

When I went to Washington in 1950 as assistant to Allen W. Dulles, then deputy director to CIA chief Walter Bedell Smith, the agency was three years old. It had been organized. like the State Department, along geographical lines, with a Far Eastern Division, a Western European Division, etc. It seemed to me that this organization was not capable of defending the United States against a new and extraordinarily successful weapon. The weapon was the international Communist front. There were seven of these fronts, all immensely powerful:

1. The International Association of Democratic Lawyers had found "documented proof" that U.S. forces in Korea were dropping canisters of poisoned mosquitoes on North Korean cities and were following a "systematic procedure of torturing civilians, individually and en masse."

2. The World Peace Council had conducted a successful operation called the Stockholm Peace Appeal, a petition signed by more than two million Americans. Most of them, I hope, were in ignorance of the council's program: "The peace movement. . . has set itself the aim to frustrate the aggressive plans of American and English imperialists... The heroic Soviet army is the powerful sentinel of peace."

3. The Women's International Democratic Federation was preparing a Vienna conference of delegates from 40 countries who resolved: "Our children cannot be safe until American war-mongers are silenced." The meeting cost the Russians six million dollars.

4. The International Union of Students had the active participation of nearly every student organization in the world. At an estimated cost of $50 million a year, it stressed the hopeless future of the young under any form of society except that dedicated to peace and freedom, as in Russia.

5. The World Federation of Democratic Youth appealed to the non- intellectual young. In 1951, 25,000 young people were brought to Berlin from all over the world, to be harangued (mostly about American atrocities). The estimated cost: $50 million.

6. The International Organization of Journalists was founded in Copenhagen in 1946 by a non-Communist majority. A year later the Communists took it over. By 1950 it was an active supporter of every Communist cause.

7. The World Federation of Trade Unions controlled the two most powerful labor unions in France and Italy and took its orders directly from Soviet Intelligence. Yet it was able to mask its Communist allegiance so successfully that the C.I.O. belonged to it for a time.

All in all, the CIA estimated, the Soviet Union was annually spending $250 million on its various fronts. They were worth every penny of it. Consider what they had accomplished.

First, they had stolen the great words. Years after I left the CIA, the late United Nations Ambassador Adlai Stevenson told me how he had been outraged when delegates from under-developed countries, young men who had come to maturity during the cold war, assumed that anyone who was for "Peace" and "Freedom" and "Justice" must also be for Communism.

Second, by constant repetition of the twin promises of the Russian revolution-the promises of a classless society and of a transformed mankind-the fronts had thrown a peculiar spell over some of the world's intellectuals, artists, writers, scientists, many of whom behaved like disciplined party-liners.

Third, millions of people who would not consciously have supported the interests of the Soviet Union had joined organizations devoted ostensibly to good causes, but secretly owned and operated by and for the Kremlin.

How odd, I thought to myself as I watched these developments, that Communists, who are afraid to join anything but the Communist Party, should gain mass allies through organizational war while we Americans, who join everything, were sitting here tongue-tied.

And so it came about that I had a chat with Allen Dulles. It was late in the day and his secretary had gone. I told him I thought the CIA ought to take on the Russians by penetrating a battery of international fronts. I told him I thought it should be a worldwide operation with a single headquarters.

"You know," he said, leaning back in his chair and lighting his pipe, "I think you may have something there. There's no doubt in my mind that we're losing the cold war. Why don't you take it up down below?"

It was nearly three months later that I came to his office again - this time to resign. On the morning of that day there had been a meeting for which my assistants and I had prepared ourselves carefully. We had been studying Russian front movements, and working out a counteroffensive. We knew that the men who ran CIA's area divisions were jealous of their power. But we thought we had logic on our side. And surely logic would appeal to Frank Wisner.

Frank Wisner, in my view, was an authentic American hero. A war hero. A cold-war hero. He died by his own hand in 1965. But he had been crushed long before by the dangerous detail connected with cold-war operations. At this point in my story, however, he was still gay, almost boyishly charming, cool yet coiled, a low hurdler from Mississippi constrained by a vest.

He had one of those purposefully obscure CIA titles: Director of Policy Co-ordination. But everyone knew that he had run CIA since the death of the war-time OSS, run it through a succession of rabbit warrens hidden in the bureaucracy of the State Department, run it when nobody but Frank Wisner cared whether the country had an intelligence service. Now that it was clear that Bedell Smith and Allen Dulles were really going to take over, Frank Wisner still ran it while they tried to learn what it was they were supposed to run.

And so, as we prepared for the meeting, it was decided that I should pitch my argument to Wisner. He knew more than the others. He could overrule them.

The others sat in front of me in straight-backed chairs, wearing the troubled looks of responsibility. I began by assuring them that I proposed to do nothing in any area without the approval of the chief of that area. I thought, when I finished, that I had made a good case. Wisner gestured at the Chief, Western Europe. "Frank," came the response, "this is just another one of those goddamned proposals for getting into everybody's hair."

One by one the others agreed. Only Richard G. Stilwell, the Chief, Far East, a hard-driving soldier in civilian clothes who now commands U.S. forces in Thailand, said he had no objection. We all waited to hear what Wisner would say.

Incredibly, he put his hands out, palms down. "Well," he said, looking at me, "you heard the verdict."

Just as incredibly, he smiled.

Sadly I walked down the long hall, and sadly reported to my staff that the day was lost. Then I went to Mr. Dulles's office and resigned. "Oh," said Mr. Dulles, blandly, "Frank and I had talked about his decision. I overruled him." He looked up at me from over his papers. "He asked me to."

Thus was the International Organization Division of CIA born, and thus began the first centralized effort to combat Communist fronts.

Perhaps "combat" does not describe the relative strengths brought to battle. For we started with nothing but the truth. Yet within three years we had made solid accomplishments. Few of them would have been possible without undercover methods.

I remember the enormous joy I got when the Boston Symphony Orchestra won more acclaim for the U.S. in Paris than John Foster Dulles or Dwight D. Eisenhower could have bought with a hundred speeches. And then there was Encounter, the magazine published in England and dedicated to the proposition that cultural achievement and political freedom were interdependent. Money for both the orchestra's tour and the magazine's publication came from the CIA, and few outside the CIA knew about it. We had placed one agent in a Europe-based organization of intellectuals called the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Another agent became an editor of Encounter. The agents could not only propose anti-Communist programs to the official leaders of the organizations but they could also suggest ways and means to solve the inevitable budgetary problems. Why not see if the needed money could be obtained from "American foundations"? As the agents knew, the CIA-financed foundations were quite generous when it came to the national interest.

I remember with great pleasure the day an agent came in with the news that four national student organizations had broken away from the Communist International Union of Students and joined our student outfit instead. I remember how Eleanor Roosevelt, glad to help our new International Committee of Women, answered point for point the charges about germ warfare that the Communist women's organization had put forward. I remember the organization of seamen's unions in India and in the Baltic ports.

There were, of course, difficulties, sometimes unexpected. One was the World Assembly of Youth.

We were casting about for something to compete with the Soviet Union in its hold over young people when we discovered this organization based in Dakar. It was dwindling in membership, and apparently not doing much.

After a careful assessment, we decided to put an agent into the assembly. It took a minimum of six months and often a year just to get a man into an organization. Thereafter, except for what advice and help we could lend, he was on his own. But, in this case, - we couldn't give any help whatsoever The agent couldn't find anybody in the organization who wanted any.

The mystery was eventually solved by the man on the spot. WAY, as we had come to call it, was the creature of French intelligence - the Deuxième Bureau. Two French agents held key WAY posts. The French Communist Party seemed strong enough to win a general election. French intelligence was waiting to see what would happen.

We didn't wait. Within a year our man brought about the defeat of his two fellow officers in an election. After that, WAY took a pro-Western stand. But our greatest difficulty was with labor. When I left the agency in 1954, we were still worrying about the problem. It was personified by Jay Lovestone, assistant to David Dubinsky in the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union.

Once chief of the Communist Party in the United States, Lovestone had an enormous grasp of foreign-intelligence operations. In 1947 the Communist Confèdèration Gènèrale du Travail led a strike in Paris which came very near to paralyzing the French economy. A takeover of the government was feared.

Into this crisis stepped Lovestone and his assistant, Irving Brown. With funds from Dubinsky's union, they organized Force Ouvrière, a non-Communist union. When they ran out of money, they appealed to the CIA. Thus began the secret subsidy of free trade unions which soon spread to Italy. Without that subsidy, postwar history might have gone very differently.

But though Lovestone wanted our money, he didn't want to tell us precisely how he spent it. We knew that non-Communist unions in France and Italy were holding their own. We knew that he was paying them nearly two million dollars annually. In his view, what more did we need to know?

We countered that the unions were not growing as rapidly as we wished and that many members were not paying dues. We wanted to be consulted as to how to correct these weaknesses.

I appealed to a high and responsible labor leader. He kept repeating, "Lovestone and his bunch do a good job."

And so they did. After that meeting, so did we. We cut the subsidy down, and with the money saved we set up new networks in other international labor organizations. Within two years the free labor movement, still holding its own in France and Italy, was going even better elsewhere.

Looking back now, it seems to me that the argument was largely a waste of time. The only argument that mattered was the one with the Communists for the loyalty of millions of workers. That argument, with the help of Lovestone and Brown, was effectively made.

By 1953 we were operating or influencing international organizations in every field where Communist fronts had previously seized ground, and in some where they had not even begun to operate. The money we spent was very little by Soviet standards. But that was reflected in the first rule of our operational plan: "Limit the money to amounts private organizations can credibly spend." The other rules were equally obvious: "Use legitimate, existing organizations; disguise the extent of American interest: protect the integrity of the organization by not requiring it to support every aspect of official American policy."

Such was the status of the organizational weapon when I left the CIA. No doubt it grew stronger later on, as those who took charge gained experience. Was it a good thing to forge such a weapon? In my opinion then-and now-it was essential.

Was it "immoral," "wrong," "disgraceful"? Only in the sense that war itself is immoral, wrong and disgraceful.

For the cold war was and is a war, fought with ideas instead of bombs. And our country has had a clear-cut choice: Either we win the war or lose it. This war is still going on, and I do not mean to imply that we have won it. But we have not lost it either.

It is now 12 years since Winston Churchill accurately defined the world as "divided intellectually and to a large extent geographically between the creeds of Communist discipline and individual freedom." I have heard it said that this definition is no longer accurate. I share the hope that John Kennedy's appeal to the Russians "to help us make the world safe for diversity" reflects the spirit of a new age.

But I am not banking on it, and neither, in my opinion, was the late President. The choice between innocence and power involves the most difficult of decisions. But when an adversary attacks with his weapons disguised as good works, to choose innocence is to choose defeat. So long as the Soviet Union attacks deviously we shall need weapons to fight back, and a government locked in a power struggle cannot acknowledge all the programs it must carry out to cope with its enemies. The weapons we need now cannot, alas, be the same ones that we first used in the 1950's. But the new weapons should be capable of the same affirmative response as the ones we forged 17 years ago, when it seemed that the Communists, unchecked, would win the alliance of most of the world.

(2) Tom Braden, interview included in the Granada Television program, World in Action: The Rise and Fall of the CIA (June, 1975)

It never had to account for the money it spent except to the President if the President wanted to know how much money it was spending. But otherwise the funds were not only unaccountable, they were unvouchered, so there was really no means of checking them - "unvouchered funds" meaning expenditures that don't have to be accounted for.... If the director of CIA wanted to extend a present, say, to someone in Europe - a Labour leader - suppose he just thought, This man can use fifty thousand dollars, he's working well and doing a good job - he could hand it to him and never have to account to anybody... I don't mean to imply that there were a great many of them that were handed out as Christmas presents. They were handed out for work well performed or in order to perform work well.... Politicians in Europe, particularly right after the war, got a lot of money from the CIA....

Since it was unaccountable, it could hire as many people as it wanted. It never had to say to any committee - no committee said to it - "You can only have so many men." It could do exactly as it pleased. It made preparations therefore for every contingency. It could hire armies; it could buy banks. There was simply no limit to the money it could spend and no limit to the people it could hire and no limit to the activities it could decide were necessary to conduct the war - the secret war.... It was a multinational. Maybe it was one of the first.

Journalists were a target, labor unions a particular target - that was one of the activities in which the communists spent the most money. They set up a successful communist labor union in France right after the war. We countered it with Force Ouvriere. They set up this very successful communist labor union in Italy, and we countered it with another union.... We had a vast project targeted on the intellectuals - "the battle for Picasso's mind," if you will. The communists set up fronts which they effectively enticed a great many particularly the French intellectuals to join. We tried to set up a counterfront. (This was done through funding of social and cultural organizations such as the Pan-American Foundation, the International Marketing Institute, the International Development Foundation, the American Society of African Culture, and the Congress of Cultural Freedom.) I think the budget for the Congress of Cultural Freedom one year that I had charge of it was about $800,000, $900,000, which included, of course, the subsidy for the Congress's magazine, Encounter. That doesn't mean that everybody that worked for Encounter or everybody who wrote for Encounter knew anything about it. Most of the people who worked for Encounter and all but one of the men who ran it had no idea that it was paid for by the CIA.

(3) Tom Braden, interviewed by John Ranelagh (14th November, 1983)

I did not initiate the activities of the agency with the CIO. The guy who did that was Allen. Allen was very much interested in the labor movement and the labor potentiality, and although I came from that corner and was idealistically pro-labor since the days of the New Deal, I didn't have the concept that Allen did. The first job I was given when I got to the agency, even before the division that I headed was created, was that Allen wanted me to stay in touch with the labor guys, which I did. I got to know the people at the CIO better than the people at the American Federation of Labor, which in December 1955 merged with the CIO.

There was a guy named Mike Ross that ran the CIO and Jay Lovestone ran the AFL side. Irving Brown ran around Europe organizing things, and Jay Lovestone sent the money. Allen was giving Lovestone money long before I came into the agency, and I think he was doing only what had been done before. I think the AFL/CIO interest in protecting the docks in Marseilles and things like that antedated the establishment of the agency. The secret funding of the AFL and CIO by the CIA I have always thought predated the agency. I suspect it was done by the OSS or the army or State Department.

(4) Harry Kelber, AFL-CIO’s Dark Past, Labor Educator (15th November, 2004)

On December 10, 1948, Matthew Woll, president of the photoengravers union and one of the four labor leaders on the AFL's Free Trade Union Committee, wrote Frank Wisner, a top officer of the Central Intelligence Agency: "This is to introduce Jay Lovestone… He is duly authorized to cooperate with you in behalf of our organization and to arrange for close contact and reciprocal assistance in all matters."

Thus, the AFL began a relationship with the intelligence agency that was to endure for better than two decades. Wisner recognized that the FTUC could be an important intelligence-gathering asset and was willing to pay a substantial price for its assistance, said to have amounted to many millions of dollars over the years.

From Lovestone's perspective, the additional funding would help him expand operations in China, Japan, India, Africa and the Arab countries. Although he chafed at having to make reports to Wisner, he needed the agency's help. While he supplied the CIA with intelligence reports from his FTUC operatives, he also received information from Wisner, who advocated "support of anti-communists in free countries."

Lovestone had no trouble cooking the FTUC's balance sheets from the prying eyes of any dissident. In 1949, for example, AFL-affiliated unions contributed $56,000 to the committee, but an additional $203,000 was attributed to "individuals," actually the CIA. In 1950, the agency funneled another $202,000 to the FTUC; in later years, the agency's funding to the AFL was kept secret, with the amount dependent on the size and nature of the covert operation.

Lovestone's very extensive, and expensive, anti-communist operations in Europe were largely financed from money siphoned off from the Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Plan), which provided $13 billion to Western European nations between 1948 and 1950.

Under the Plan's rules, each country receiving financial aid had to refund 5% of the total to U.S. occupation forces for administrative expenses. That turned out to be a slush fund (referred to as the "sugar fund") of more than $800 million that the Free Trade Union Committee was allowed to draw from and spread lavishly to subvert a gallery of European labor leaders to support whatever American policy was demanded of them.

When Marshall Plan funds dried up, Lovestone became more dependent on CIA funding. But the CIA's new director, Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, who had been Eisenhower's chief of staff in Europe during World War II, was a tough administrator who started questioning the expenditures for the AFL's clandestine operations.

To clarify the relationship, a "summit" meeting was held on November 24, 1950. In attendance for the AFL were Meany, Dubinsky, Woll and Lovestone. The CIA was represented by Smith, its director, and his top assistant, Frank Wisner.

There was general agreement that the collaboration had worked well and should continue. But Lovestone, while complimenting the CIA for the assistance it had given the AFL in several emergency situations, still insisted that improvements had to be made in the relationship. He had given the CIA a list of the funding he required for special projects, but it had been ignored. Smith said he would review the proposals.

When Smith brought up the idea of including the CIO into the agency's operations, the AFL group quickly voiced their strong objections. They said he CIO was inexperienced in this kind of activity and was riddled with communists and other undesirable elements. Lovestone said that if the CIO were brought in, all their work would be placed in jeopardy. The CIO could not be trusted to maintain the secrecy that was required by both the AFL and CIA operations.

Meany said he was worried that the CIO would get some of its friends in the Truman administration to recommend that they share equally in funding and participation in international labor activity. (Just a few months earlier, the CIO had expelled eleven international unions with over one million members for "following the Communist Party line.") Meany threatened to withdraw from the arrangement with the CIA if the CIO were brought into the partnership.

But to Smith and Wisner, it seemed absurd to work closely with one wing of the labor movement while totally ignoring the other. The best that the AFL guests could get out of them was that enlisting the cooperation of the CIO was not imminent.

The propriety of an American labor movement becoming the instrument or partner of a government intelligence agency was fully acceptable to the Meany-Dubinsky-Woll trio, as long as it was in the service of an anti-Soviet crusade and the defeat of communist-led unions. Nor did any US union leader dare to challenge the clandestine, quid pro quo relationship between organized labor and the international spy agency.

It was Thomas Braden, an assistant to CIA director Allan Dulles, who became the contact man with the CIO. Walter Reuther, the UAW president, received $50,000 in cash from Braden, who flew to Detroit to deliver it.

There are no public records of how much money the CIA gave both branches of the labor movement. There was no congressional oversight of the agency. As Braden said: "The CIA could do exactly as it pleased. It could buy armies. It could buy bombs. It was one of the first world-wide multinationals."

(5) CIA and the Labour Party, Radical Research Services (1974)

The launching of the Congress for Cultural Freedom by Melvin Laskey in Berlin in 1950 was financed in the same way. Disaster threatened the Cold Warriors in 1950-51 when Congress refused to renew Marshall Aid. As Thomas Braden has confirmed, they had either to shut up shop or turn to the CIA. They chose the latter. Thus continued 17 years of secret US funding.

When, in the early sixties, it seemed to the National Security Council (NSC) that the CIA's cover was about to be blown, funding was quietly shifted to the larger charitable foundations whose directors were well aware of what was going on. The Ford, Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations moved into international affairs in a big way in 1950. Ford's international director for the next 17 years was Sheperd Stone under the NSC members Mr George Bundy, Presidential Adviser on Security, and Robert McNamara, Defence Secretary. Carnegie president was Joseph E. Johnson who organised the American end of Bilderberg. Thomas Braden was a Carnegie trustee.

Rockefeller trustees included Barry Bingham - ECA Administrator France 1949-50, chairman International Press Institute, director Asia Foundation - and Arthur Houghton, whose Foundation for Youth and Student Affairs channelled millions of dollars of CIA money into the US and world students movements. For those who continue to protest the innocence of the US (and some European) foundations, massive documentary evidence can - and will - be produced to show that in their international affairs they acted as agents of the US State Department.

But to return to the European Movement. Thomas Braden had been in the US Military Government in Germany. From 1949 to 1951 he was executive director of the American Committee on United Europe - a body resulting from a visit by Retinger and Duncan Sandys to Allen Dulles and others in the United States in July 1948. Its aims were to fund the European Movement and to bring about the establishment of a European army rearming the Germans against the USSR. It also worked closely with Cord Meyer's United World Federalists.

In a letter to Duncan Sandys, 20 January 1950, Thomas Braden wrote that the ACUE's purpose was ''not only to influence public opinion, but to sell the idea of the European Movement . . . and to justify the appeal for important sums of money."

According to Allan Hovey, Jnr., ACUE representative in Europe, the vast majority of US funds for Europe and nearly all for the European Youth Campaign (EYC) came from State Department covert funds. This was, of course, kept very secret. ACUE was a legal covering organisation.

Braden joined the CIA as Dulles' assistant in 1950 while continuing as ACUE executive director. Funds were sent to the European representative in Brussels, and those intended for the EYC were passed through a covering body in Paris - the Centre d'Action Europiènne - which submitted a monthly budget to Brussels.

Total secret US funding to the European Movement from 1947 to 1953 was £440,000. (Source: EM Archives, FIN/P/6 "European Movement: EYC Treasurer's Report 1949/53").

Thus, far from being a spontaneous expression of the desire for unity of the people of Europe, the European movement was launched by Retinger with secret money from the State Department and kept afloat with massive subventions through Thomas Braden, head of the CIA'S International Organisation Division.

(6) Andrew Roth, The Guardian (22nd May, 2004)

Melvin Lasky, who has died aged 84, was, as editor of the magazine Encounter from 1958 to 1990, and of Der Monat (the Month) for 15 years, a combatant in the struggle to keep western intellectuals in the United States' cold war camp. But in 1967, it was disclosed that both Encounter and Der Monat had been covertly financed by the US Central Intelligence Agency and Mel's reputation shrivelled...

Mel's origins in the anti-Communist Russian-Jewish community help explain why, at 22, he became literary editor of the New Leader, an organ of anti-Communist Jewish liberals. He held the post from 1942 to 1943. In 1944, Mel belatedly signed up, as a US Army combat historian in Europe.

Postwar, with the cold war, Der Monat was launched in Berlin in 1948 with Mel as editor, a job he did until 1958 and again from 1978 to 1983. His intellectual and linguistic abilities were never in question, and in 1958, as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament took off, Mel replaced Irving Kristol - co-editor since 1953 with poet Stephen Spender - on Encounter. At that time, many British intellectuals had clustered around Kingsley Martin's New Statesman, which tended towards a cold war neutrality. US government thinking was that if a Labour government were returned to power, dissident left-wing MPs would make it difficult for the US to retain Britain as a secure ally.

Encounter's function was to combat anti-Americanism by brainwashing the uncertain with pro-American articles. These were paid for at several times the rate paid by the New Statesman and offered British academics and intellectuals free US trips and expenses-paid lecture tours. There was no room for the objective-minded in this cold war to capture intellectuals.

Enormously industrious, Mel doubled up by running publishing houses for his masters. The premise was that they published pro-American books knowing that the bulk of each edition would be purchased by US agencies to donate to book-starved libraries in the third world.

Even at its peak Encounter had never claimed a circulation above 40,000. Its spider's web began to come apart in 1966-67 with publication of pieces in the New York Times and the radical magazine Ramparts. And Thomas Braden, previously a CIA divisional chief, confirmed in the Saturday Evening Post that, for more than 10 years, the CIA had subsidised Encounter through the Congress for Cultural Freedom - which it also funded - and that one of its staff was a CIA agent. (Lasky had been the CCF's sometime executive secretary). The magazine also covertly received British government money.

Mel's coeditor, Professor Frank Kermode, resigned, proclaiming he had been misled by Mel. "I was always reassured that there was no truth in the allegations about CIA funds."

Mel admitted breezily that "I probably should have told him all the painful details." Spender also quit the monthly and many contributors pulled out.

The CIA funds, had, in fact been replaced in 1964 by Cecil King's International Publishing Corporation - the then owners of the Daily Mirror - which bought the magazine. King's deputy, Hugh Cudlipp, sprang to Mel's defence, insisting that "Encounter without him [Mel] would be as interesting as Hamlet without the Prince".

(7) Richard Fletcher, How CIA Money Took the Teeth Out of Socialism (undated)

Since the Second World War the American Government and its espionage branch, the Central Intelligence Agency, have worked systematically to ensure that the Socialist parties of the free world toe a line compatible with American interests...CIA money can be traced flowing through the Congress for Cultural Freedom to such magazines as Encounter which have given Labour politicians like Anthony Crosland, Denis Healy and the late Hugh Gaitskell a platform for their campaigns to move the Labour Party away from nationalisation and CND-style pacifism. Flows of personnel link this Labour Party pressure group with the unlikely figure of Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, who has for 20 years sponsored the mysterious activities of the anti-Communist Bilderberg group launched with covert American funds.

There is no suggestion that these prominent Labour politicians have not acted in al innocence and with complete propriety. But it could be asked how such perspicacious men could fail to enquire about the source of the funds that have financed the organisations and magazines which have been so helpful to them for so long. Nevertheless, they are certainly proud of the crucial influence their activities had in the years following 1959 when they swung the British Labour Party away from its pledge to nationalisation, enshrined in the celebrated Clause IV, and back towards the commitment to NATO from which the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament had deflected it. CIA operators take the credit for helping them in this decisive intervention which changed the course of modern British history.

The cloak and dagger operations of America's Central Intelligence Agency are only a small part of its total activities. Most of its 2000 million-dollar budget and 80,000 personnel are devoted to the systematic collection of information - minute personal details about tens of thousands of politicians and political organisations in every country in the world, including Britain. And this data, stored in the world's largest filing system at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, is used not only to aid Washington's policy-machine, but in active political intervention overseas - shaping the policies of political parties, making and unmaking their leaders, boosting one internal faction against another and often establishing rival breakaway parties when other tactics fail.

In fact the CIA carries out, at a more sophisticated level, exactly the same sort of organised subversion as Stalin's Comintern in its heyday. One of its targets in the years since the Second World War has been the British Labour Party.

The Labour Party emerged from the war with immense prestige. As the sole mass working-class party in Britain it had the support of a united trades union movement whose power had been greatly enhanced by the war, and it had just achieved an unprecedented electoral victory. The established social democratic parties of Europe had been destroyed by the dictators, while in America all that remained of the socialist movement was a handful of sects whose members were numbered in hundreds. Labour was undisputed head of Europe's social democratic family.

But as the euphoria wore off, old differences began to emerge with prolonged post-war austerity. The Left wanted more Socialism and an accommodation with the Russians, while the Right wanted the battle against Communism to take precedence over further reforms at home. And those who took this latter view organised themselves around the journal Socialist Commentary, formerly the organ of anti-Marxist Socialists who had fled to Britain from Hitler's Germany. The magazine was reorganised in the autumn of 1947 with Anthony Crosland, Allan Flanders and Rita Hinden who had worked closely with the émigrés as leading contributors. And Socialist Commentary became the mouthpiece of the Right wing of the Labour Party, campaigning against Left-wingers like Aneurin Bevan, whom they denounced as dangerous extremists. Crosland, who ended the war as a captain in the Parachute Regiment, had been President of the Oxford Union, and a year later, in 1947, became Fellow and lecturer in economics at Trinity College, Oxford. Flanders was a former TUC official who became an academic specialist in industrial relations and later joined the Prices and Incomes Board set up by the Wilson Government. Rita Hinden, a University of London academic from South Africa, was secretary of the Fabian Colonial Bureau - an autonomous section of the Fabian Society which she had set up and directed since the early Forties. In this position she exercised considerable influence with Labour Ministers and officials in the Colonial Office, maintaining close links with many overseas politicians.

The new Socialist Commentary immediately set out to alert the British Labour movement to the growing dangers of international Communism, notably in a piece entitled Cominformity, written by Flanders during a period spent in the United States studying the American trade union movement. The journal's American connections were further extended by its U.S. correspondent, William C. Gausmann, who was soon to enter the American Government Service, where he rose to take charge of US propaganda in North Vietnam, while support for the moderate stand taken by Crosland, Flanders and Hinden came from David C. Williams, the London Correspondent of the New Leader, an obscure New York weekly specialising in anti-Communism. Williams made it his business to join the British Labour Party and to take an active part in the Fabian Society.

This close American interest in Socialism on the other side of the Atlantic was nothing new. During the war the American trade unions had raised large sums to rescue European labour leaders from the Nazis, and this had brought them closely in touch with American military intelligence and, in particular, with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), whose chief in Switzerland and Germany from 1942 to 1945 was Allen W. Dulles, later, of course, to become famous as head of the CIA in its heyday.

The principal union official in these secret commando operations had been Jay Lovestone, a remarkable operator who had switched from being the leader of the American Communist Party to working secretly for the US Government. And as the Allied armies advanced, Lovestone's men followed the soldiers as political commissars, trying to make sure that the liberated workers were provided with trade union and political leaders acceptable to Washington - many of these leaders being the émigrés of the Socialist Commentary group. In France, Germany, Italy and Austria the commissars provided lavish financial and material support for moderate Socialists who would draw the sting from Left-wing political movements, and the beneficiaries from this assistance survive in European politics to this day - though that is another story...

In 1953 the Congress for Cultural Freedom launched Encounter, an English language monthly which was an immediate success under the editorship of Irving Kristol, another of Levitas's New Leader protégés and an ex-Lovestoneite, and soon a bewildering range of publications in several languages had joined the CCF stable, with Encounter becoming one of the most influential journals of liberal opinion in the West.

As the CCF network grew it embraced many prominent figures in the British Labour Party -among them Anthony Crosland, who began attending CCF seminars, where he met Daniel Bell, who was at this period moving away from journalistic red-baiting in the New Leader towards academic respectability. Bell's thinking was later summarised in his book The End of Ideology, and it formed the basis of the new political thesis set out in the major work that Crosland was now writing and which was published in 1956 under the title The Future of Socialism. The book had also been influenced by the arguments put forward at the Conference of the Congress for Cultural Freedom held in the previous year in Milan, where principal participants had included Hugh Gaitskell, Denis Healey and Rita Hinden as well as Daniel Bell and a bevy of American and European politicians and academics.

Put at its simplest. Bell and his colleagues argued that growing affluence had radically transformed the working-class in Europe - and Britain - which was now virtually indistinguishable from the middle-class, and thus Marx's theory of class struggle was no longer relevant. Future political progress, they thought, would involve the gradual reform of capitalism and the spread of equality and social welfare as a consequence of continued economic growth.

Crosland's book, though not original in content, was a major achievement. In over 500 pages it clothed the long-held faith of Labour's new leader Hugh Gaitskell in the academic respectability of American political science and was immediately adopted as the gospel of the Party leadership. Labour's rank-and-file, however, still clung to their grassroots Socialism, and Gaitskell's obvious preferences for the small coterie of cultured intellectuals and visiting foreigners who met at his house in Frognal Gardens, Hampstead, alienated the Party faithful, and gave added bitterness to the internecine quarrels that were to follow Labour's defeat in the 1959 election.

In 1957 Melvin Lasky had taken over the editorship of Encounter which had, by then, cornered the West's intelligentsia through its prestige and the high fees it was able to pay. Lasky was a trusted member of Gaitskell's inner circle and was often to be seen at his parties in Hampstead, while Gaitskell became at the same time a regular contributor to the New Leader. Sol Levitas would drop in at his house on his periodic tours to see world leaders and visit the CCF in Paris.

It was during the Fifties furthermore, that Anthony Crosland, Rita Hinden and the other members of the Socialist Commentary group adopted the argument put forcibly in the New Leader that a strong united Europe was essential to protect the Atlantic Alliance from Russian attack, and European and Atlantic unity came to be synonymous in official thinking as Gaitskell and his friends moved into the Party leadership. They received transatlantic encouragement, furthermore, from a New York-based group called the American Committee on United Europe, whose leadership was openly advertised in the New York Times as including General Donovan, wartime head of OSS. George Marshall, the US Secretary of State, General Lucius D. Clay and Allen Dulles of the CIA...

But early in 1967 the US journal Ramparts revealed that since the early Fifties the National Student Association of America had, with the active connivance of its elected officers, received massive subventions from the CIA through dummy foundations and that one of these was the Fund for Youth and Student Affairs which supplied most of the budget of ISC. The International Student Conference, it appeared, had been set up by British and American Intelligence in 1950 to counteract the Communist peace offensive, and the CIA had supplied over 90 per cent, of its finance. The Congress for Cultural Freedom was similarly compromised. Michael Josselson admitted that he had been chanelling CIA money into the organisation ever since its foundation - latterly at the rate of about a million dollars a year - to support some 20 journals and a world-wide programme of political and cultural activities. Writing of Sol Levitas at the time of his death in 1961, the editor of the New Leader, William Bohm said "the most amazing part of the journalistic miracle was the man's gift for garnering the funds which were necessary to keep our paper solvent from week to week and year to year. I cannot pretend to explain how this miracle was achieved. We always worked in an atmosphere of carefree security. We knew that the necessary money would come from somewhere and that our cheques would be forthcoming."

The "Miracle" was resolved by the New York Times: the American Labour Conference for International Affairs which ran the New Leader had for many years been receiving regular subventions from the J. M. Kaplan Fund, a CIA conduit.

The CIA had taken the lessons taught back in the early Fifties by Burnham and the New Leader to heart. With its army of ex-communists and willing Socialists it had for a while beaten the Communists at their own game -but unfortunately it had not known when to stop and now the whole structure was threatened with collapse. Rallying to the agency's support, Thomas Braden, the official responsible for its move into private organisations, and Executive Director of the American Committee on United Europe, explained that Irving Brown and Lovestone had done a fine job in cleaning up the unions in post-war Europe. When they ran out of money, he said, he had persuaded Dulles to back them, and from this beginning the worldwide operation mushroomed.

Another ex-CIA official, Richard Bissell, who organised the Bay of Pigs invasion, explained the Agency's attitude to foreign politicians: "Only by knowing the principal players well do you have a chance of careful prediction. There is real scope for action in this area: the technique is essentially that of 'penetration' . . . Many of the 'penetrations' don't take the form of 'hiring' but of establishing friendly relationships which may or may not be furthered by the provision of money from time to time. In some countries the CIA representative has served as a close counsellor... of the chief of state."

After these disclosures the CCF changed its name to the International Association for Cultural Freedom. Michael Josselson resigned - but was retained as a consultant - and the Ford Foundation agreed to pick up the bills. And the Director of the new Association is none other than Shepard Stone, the Bilderberg organiser who channelled US Government money to Joseph Retinger in the early Fifties to build the European Movement and then became International Director of the Ford Foundation.

(8) Tom Braden, What's Wrong with the CIA? (5th April, 1975)

We are gathered, four of us CIA division chiefs and deputies, in the office of our agency's director, an urbane and charming man. He is seated at his desk, puffing nervously on his pipe and asking us questions.

Allen W. Dulles is fretting on this morning in the early fifties, as indeed, he has fretted most mornings. You can't be in the middle of building an enormous spy house, running agents into Russia and elsewhere, worrying about Joseph McCarthy, planning to overthrow a government in Guatemala, and helping to elect another in Italy, without fretting.

But on this particular morning, Dulles is due for an appearance before Sen. Richard B. Russell's Armed Services Committee, and the question he is pondering as he puffs on his pipe is whether to tell the senators what is making him fret. He has just spent a lot of money on buying an intelligence network, and the network has turned out to be worthless. In fact, it's a little worse than worthless. All that money, Dulles now suspects, went to the KGB.

Therefore, the questions are somber, and so are the answers. At last, Dulles rises. "Well," he says, "I guess I'll have to fudge the truth a little."

His eyes twinkle at the word fudge, then suddenly turn serious. He twists his slightly stooped shoulders into the old tweed topcoat and heads for the door. But he turns back. "I'll tell the truth to Dick (Russell) he says. "I always do." Then the twinkle returns, and he adds, with a chuckle, "That is, if Dick wants to know."

The reason I recall the above scene in detail is that lately I have been asking myself what's wrong with the CIA. Two committees of Congress and one from the executive branch are asking the question, too. But they are asking out of concern for national policy. I am asking for a different reason. I once worked for the CIA. I regard the time I spent there as worthwhile duty. I look back upon the men with whom I worked as able and honorable. So for me, the question, "What's wrong with the CIA?" is both personal and poignant.

Old friends of mine have been caught in evasions or worse. People I worked with have violated the law. Men whose ability I respected have planned operations that ended in embarrassment or disaster. What's wrong with these people? What's wrong with the CIA?

Ask yourself a question often enough, and sometimes the mind will respond with a memory. The memory my mind reported back is that scene in Allen Dulles' office. It seemed, at first blush, a commonplace, nonconsequential episode. But the more it fixed itself in my mind, the more it seemed to me that it helped to answer my question about what's wrong with the agency. Let me explain.

The first thing this scene reveals is the sheer power that Dulles and his agency had. Only a man with extraordinary power could make a mistake involving a great many of the taxpayers' dollars and not have to explain it. Allen Dulles had extraordinary power.

Power flowed to him, and through him, to the CIA, partly because his brother was Secretary of State, partly because his reputation as the master spy of World War II hung over him like a mysterious halo, partly because his senior partnership in the prestigious New York law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell impressed the small-town lawyers of Congress.

Moreover, events helped keep power flowing. The country was fighting a shooting war in Korea and a Cold War in Western Europe, and the CIA was sole authority on the plans and potential of the real enemy. To argue against the CIA was to argue against knowledge. Only Joseph McCarthy would run such a risk.

Indeed, McCarthy unwittingly added to the power of the CIA. He attacked the agency and when, in the showdown, Dulles won, his victory vastly increased the respectability of what people then called "the cause" of anti-communism. "Don't join the book burners," Eisenhower had said. That was the bad way to fight communism. The good way was the CIA.

Power was the first thing that went wrong with the CIA. There was too much of it, and it was too easy to bring to bear – on the State Department, on other government agencies, on the patriotic businessmen of New York, and on the foundations whose directorships they occupied. The agency's power overwhelmed the Congress, the press, and therefore the people.

I'm not saying that this power didn't help win the Cold War, and I believe the Cold War was a good war to win. But the power enabled the CIA to continue Cold War operations 10 and 15 years after the Cold War was won. Under Allen Dulles the power was unquestioned, and after he left, the habit of not questioning remained.

I remember the time I walked over to the State Department to get formal approval for some CIA project involving a few hundred thousand dollars and a publication in Europe. The desk man at the State Department balked. Imagine. He balked – and at an operation designed to combat what I knew for certain was a similar Soviet operation. I was astonished. But I didn't argue. I knew what would happen. I would report to the director, who would get his brother on the phone: "Foster, one of your people seems to be a little less than cooperative." That is power.

The second thing that's wrong with the CIA is arrogance, and the scene I've mentioned above shows that, too. Allen Dulles's private joke about "fudging" was arrogant, and so was the suggestion that "Dick" might not want to know. An organization that does not have to answer for mistakes is certain to become arrogant.

It is not a cardinal sin, this fault, and sometimes it squints toward virtue. It might be argued, for example, that only arrogant men would insist on building the U-2 spy plane within a time frame which the military experts said could not be met. Yet in the days before satellite surveillance, the U-2 spy plane was the most useful means of keeping the peace. It assured this country's leaders that Russia was not planning an attack. But if arrogance built the plane quickly, it also destroyed it. For surely it was arrogant to keep it flying through Soviet airspace after it was suspected that the Russians were literally zeroing in on overflying U-2s.

I wonder whether the arrogance of the CIA may not have been battlefield-related – a holdover from World War II machismo and derring-do. The leaders of the agency were, almost to a man, veterans of OSS, the CIA's wartime predecessor. Take, for example, the men whose faces I now recall, standing there in the director's office.

One had run a spy-and-operations network into German from German-occupied territory. Another had volunteered to parachute into Field Marshall Kesselring's headquarters grounds with terms for his surrender. A third had crash-landed in Norway and, having lost half his men, came up, nevertheless, blowing up bridges.

OSS men who became CIA men were unusual people who had volunteered to carry out unusual orders and to take unusual risks. More over, they were impressed, more than most soldiers can be impressed, with the absolute necessity for secrecy and the certainly penalty that awaited the breach of it.

But they had another quality that set them apart. For some reason that psychologists could perhaps explain, a man who volunteers to go on an extremely dangerous mission, alone or with two or three helpers, is likely to be not only brave and resourceful but also somewhat vain. Relatively few men volunteered to jump into German or Japanese territory during World War II. Those who did volunteer were conscious that they were, in a word, "different."

Once these men had landed behind the lines, the difference took on outward symbols. They were alone, Americans in a country full of French or Greek or Italian or Chinese. Often they were treated with great respect. Sometimes, as mere lieutenants, they commanded thousands of men. At a word from them, American or British planes came over to drop supplies to these men. They earned the love and respect that conquered people felt for the great democracy called America. Inevitably, they began to think of themselves individually and collectively as representing the national honor.

Is it not possible that men who have learned to do everything in secrecy, who are accustomed to strange assignments, and who think of themselves as embodying their country, are peculiarly susceptible to imperial Presidencies such as those of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon? Have they not in fact trained themselves to behave as a power elite?

To power and arrogance add the mystique of the inside-outside syndrome. That scene in the director's office defines the problem. Dulles was leveling with his assistants, and they were leveling with him. An agent or a station chief or an official of the CIA who didn't level – who departed the slightest degree from a faithful account of what he knew or what he had done – was a danger to operations and to lives. Such a man couldn't last a day in the CIA.

But truth was reserved for the inside. To the outsider, CIA men learned to lie, to lie consciously and deliberately without the slightest twinge of the guilt that most men feel when they tell a deliberate lie.

The inside-outside syndrome is unavoidable in a secret intelligence agency. You bring a group of people together, bind them with an oath, test their loyalty periodically with machines, spy on them to make sure they're not meeting secretly with someone from the Czech Embassy, cushion them from the rest of the world with a false cover story, teach them to lie because lying is in the national interest, and they do not behave like other men.

They do not come home from work and answer truthfully the question, "What did you do today, darling?" When they chat with their neighbors, they lie about their jobs. In their compartmentalized, need-to-know jobs, it is perfectly excusable for one CIA man to like to another if the other doesn't need to know.

Thus it was ritual for Allen Dulles to "fudge," and often he didn't have to. Senator Russell might say, "The chairman has conferred with the director about this question, which touches a very sensitive matter." The question would be withdrawn.

Another technique for dealing with an outsider was the truthful non-response. Consider the following exchange between Sen. Claiborne Pell (D. R.I.) and Richard Helms. (The Exchange was concerned with spying on Americans, an illegal act under the terms of the law that created the CIA.)

Senator Pell (referring to spying on antiwar demonstrations):

"But those all occurred within the continental shores of the Untied States and for that reason you had the justifiable reason to decline [to] move in there because the events were outside your ambit."

Mr. Helms: "Absolutely, and I have never been lacking in clarity in my mind since I have been director, that this is simply not acceptable not only to Congress but to the public of the United States."

No doubt that answer was truthful. No doubt Helms did think that domestic spying was not acceptable. But he was doing it, and he didn't say he wasn't.

Finally, of course, there is the direct lie. Here is another excerpt from 1973 testimony by Helms:

Senator Symington (D. Mo.): "Did you try, in the Central Intelligence Agency, to overthrow the government of Chile?"

Helms: "No, Sir."

Symington: "Did you have any money passed to the opponents of Allende?"

Helms: "No, Sir."

Helms was under oath. Therefore, he must have considered his answer carefully. Obviously, he came to the insider's conclusion: that his duty to protect the inside outweighed his outsider's oath. Or to put it another way, the law of the inside comes first.

Allen Dulles once remarked that if necessary, he would like to anybody about the CIA except the President. "I never had the slightest qualms about lying to an outsider," a CIA veteran remarked recently. "Why does an outsider need to know?"

So much for the lessons of memory. Power, arrogance, and the inside-outside syndrome are what's wrong with the CIA, and to some extent, the faults are occupational and even necessary tools for the job.

But the events of the Cold War and the coincidence of Allen Dulles' having such enormous discretionary powers enlarged occupational risks until they became faults, and the faults created a monstrosity.

Power built a vast bureaucracy and a ridiculous monument in Langley, Va. Arrogance fostered the belief that a few hundred exiles could land on a beach and hold off Castro's army.

The inside-outside syndrome withheld the truth from Adlai Stevenson so that he was forced to make a spectacle of himself on the floor of the United Nations by denying that the United States had anything to do with the invasion of Cuba. The same syndrome has made a sad and worried man of Richard Helms.

It's a shame what happened to the CIA. It could have consisted of a few hundred scholars to analyze intelligence, a few hundred spies in key positions, and a few hundred operators ready to carry out rare tasks of derring-do.

Instead, it became a gargantnan monster, owning properly all over the world, running airplanes and newspapers and radio stations and banks and armies and navies, offering temptation to successive Secretaries of State, and giving at least one President a brilliant idea; Since the machinery for deceit existed, why not use it?

Richard Helms should have said no to Richard Nixon. But as a victim of the inside-outside syndrome, Helms could only ask Watergate's most plaintive question: "Who would have thought that it would someday be judged a crime to carry out the orders of the President of the United States?"

A shame – and a peculiarly American shame. For this is the only country in the world which doesn't recognize the fact that some things are better if they are small.

We'll need intelligence in the future. And once in a while, once in a great while, we may need cover action, too. But, at the moment, we have nothing. The revelations of Watergate and the investigations that have followed have done their work. The CIA's power is gone. Its arrogance has turned to fear. The inside-outside syndrome has been broken. Former agents write books naming other agents. Director William Colby goes to the Justice Department with evidence that his predecessor violated the law. The house that Allen Dulles built is divided and torn.

The end is not in sight. Various committees now investigating the agency will doubtless find error. They will recommend change, they will reshuffle, they will adjust. But they will leave the monster intact, and even if the monster never makes another mistake, never again over-reaches itself – even, indeed, if like some other government agencies, it never does anything at all – it will, by existing, go right on creating and perpetuating the myths that always accompanied the presence of the monster.

We know the myths. They circulate throughout the land wherever there are bars and bowling alleys: that the CIA killed John Kennedy; that the CIA crippled George Wallace; that an unexplained airplane crash, a big gold heist, were all the work of the CIA.

These myths are ridiculous, but they will exist as long as the monster exists.

The fact that millions believe the myths raises once again the old question which OSS men used to argue after the war: Can a free and open society engage in covert operations?

After nearly 30 years of trial, the evidence ought to be in. The evidence demonstrates, it seems to me, that a free and open society cannot engage in covert operations – not, at any rate, in the kind of large, intricate covert operations of which the CIA has been capable.

I don't argue solely from the box score. But let's look at the box score. It reveals many famous failures. Too easily, they prove the point. Consider what the CIA deems is known successes: Does anybody remember Arbenz in Guatemala? What good was achieved by the overthrow of Arbenz? Would it really have made any difference to this country if we hadn't overthrown Arbenz?

And Allende? How much good did it do the American people to overthrow Allende? How much bad?

Was it essential – even granted the sticky question of succession – to keep those Greek colonels in power for so long?

We used to think that it was a great triumph that the CIA kept the Shah of Iran on his throne against the onslaught of Mossadegh. Are we grateful still?

The uprisings during the last phase of the Cold War, and those dead bodies on the streets of Poland, East Germany, and Hungry: to what avail?

But the box score does not tell the whole story. We paid a high price for that box score. Shame and embarrassment is a high price? Doubt, mistrust, and fear is a high price. The public myths are a high price, and so is the guilty knowledge that we own an establishment devoted to opposing the ideals we profess.