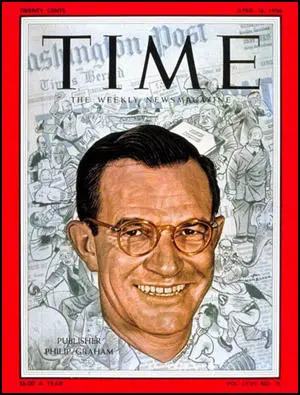

Philip Graham

Philip Graham, the son of a mining engineer, was born in Terry, South Dakota, on 18th July, 1915. The family moved to Florida when Graham was a child and he was educated at Miami High School and the University of Florida. Graham moved on to the Harvard University Law School where he was editor of the Law Review.

In 1940 Graham married Katharine Meyer. The following year he became clerk to Felix Frankfurter. Graham joined the Army Air Corps in 1942. He worked as an assistant to William Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). In 1944 Graham was recruited into the "Special Branch, a super-secret part of Intelligence, run by Colonel Al McCormick". He later worked under General George Kenney, commander of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific. Graham was sent to China where he worked with John K. Singlaub, Ray S. Cline, Richard Helms, E. Howard Hunt, Mitchell WerBell, Jake Esterline, Paul Helliwell, Robert Emmett Johnson and Lucien Conein. Others working in China at that time included Tommy Corcoran, Whiting Willauer and William Pawley.

Graham's father-in-law was Eugene Meyer, the owner of the Washington Post. In 1946 Meyer appointed Graham as associate publisher. He eventually took over business side of the newspaper's operations. He also played an important role in the paper's editorial policy.

Graham lived in Washington where he associated with a group of journalists, politicians and government officials that became known as the Georgetown Set. This included Frank Wisner, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Richard Bissell, Desmond FitzGerald, Joseph Alsop, Stewart Alsop, Tracy Barnes, Thomas Braden, David Bruce, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen, Cord Meyer, James Angleton, William Averill Harriman, John McCloy, Felix Frankfurter, John Sherman Cooper, James Reston, Allen W. Dulles and Paul Nitze.

Most men brought their wives to these gatherings. Members of what was later called the Georgetown Ladies' Social Club included Katharine Graham, Mary Pinchot Meyer, Sally Reston, Polly Wisner, Joan Braden, Lorraine Cooper, Evangeline Bruce, Avis Bohlen, Janet Barnes, Tish Alsop, Cynthia Helms, Marietta FitzGerald, Phyllis Nitze and Annie Bissell.

Graham met Lyndon B. Johnson in 1953. Graham believed that one day Johnson would make a good president. Graham told Johnson that his main problem was that he was perceived in Washington as someone under the control of the Texas oil and gas industry. Graham added that his attitude towards civil rights was also hurting him with liberals in the North. He was advised to go a "bit beyond (Richard) Russell and yet far short of (Hubert) Humphrey".

Graham was a supporter of the Democratic Party and did what he could to get Johnson the nomination in 1960. When John F. Kennedy defeated Johnson he sent Clark Clifford to ask Stuart Symington to be his running-mate. Symington accepted the post but said: "I bet you a hundred dollars that no matter what he says, Jack will not make me his running mate. He will have to pick Lyndon".

In the background Graham and Joseph Alsop were attempting to persuade John F. Kennedy to appoint Lyndon B. Johnson instead. Despite the objection of Robert Kennedy and other leading advisers, Kennedy decided to replace Symington with Johnson.

After his election Kennedy was persuaded by Graham to appoint his friend, Douglas Dillon as Secretary of the Treasury. He also influenced Kennedy's decision to appoint Arthur Schlesinger, his former OSS buddy, as his adviser and David Bruce, as ambassador to London.

It is claimed that Graham had close links with the Central Intelligence Agency. He had a close relationship with Tracy Barnes and Frank Wisner. it has been claimed that Graham played an important role in Operation Mockingbird, the CIA program to infiltrate domestic American media. According to Katherine Graham, her husband worked overtime at the Post during the Bay of Pigs operation to protect the reputations of his friends who had organized the ill-fated venture.

As president of the Washington Post Company he purchased Washington Times-Herald. Later he took control of radio and television stations WTOP (Washington) and WJXT (Jacksonville). In 1961 Graham purchased Newsweek. The following year he took control of America's two leading art magazines, Art News and Portfolio. The main person involved in arranging Graham's takeover of other media companies was Fritz Beebe. He ran the law firm Cravath, Swaine, & Moore. This was the company owned by Al McCormick, who Graham met during the war. Averell Harriman was another one involved in these negotiations.

Philip Graham committed suicide by killing himself with a shotgun on 3rd August, 1963.

Primary Sources

(1) Philip Graham, speech at the American Power Company in Canton, Ohio (February, 1960)

Where I get in difficulty - at times almost unbearable difficultyis when I try to examine the meaning of what I am engaged in. When these difficulties get too great we in the newspaper business... retreat to the ritual of reciting old rules that we know are meaningless.

We say that we just print the objective news in our news columns and confine our opinions to the editorial page. Yet we know that while this has some merit as an over-simplified slogan of good intentions, it also has a strong smell of pure baloney.

If we keep wages too low in some few areas where unions still let us do it or if we neglect decent working amenities as long as we can avoid the cost, we defend ourselves by muttering about our concern for stockholders. As though by announcing compassion for a relatively anonymous and absent group we can justify a lack of compassion for people we spend our working days with.

If we are brutally careless about printing something that maligns the character of some concrete individual, we are apt to wave the abstract flag of freedom of speech in order to avoid the embarrassment of a concrete apology.

If we are pressed even harder, we may salve our consciences by saying that after all there are libel laws. And as soon as we say that we redouble our efforts to make those laws as toothless as we possibly can.

And if we are pressed really quite hard, we can finally shrug our shoulders and say, "Well, after all we have to live." Then we can only hope no one will ask the ultimate question: "Why?"

I certainly have been guilty of all those stupid actions - and a great many more stupid. And I suppose that more than a few of you have done as poorly.

What I prefer to recall are those rare occasions when I have had some better sense of the meaning of what I am engaged in. In those moments I have realized that our problems are relatively simple and that some simple, ancient, moral precepts are often reliable business tools. In those moments I have been able to keep in mind that it really doesn't matter whether I am kept in my job. In those moments I have been able to look straight at the frailty of my judgment. And finally I have been honest enough to recognize that a few a very few great issues about the meaning of life are the only issues which deserve to be considered truly complex... by paying attention to the broader meaning of what we are engaged in, we may be able to join our passion to our intelligence. And such a juncture, even on the part of but one individual, can represent a significant step forward on the long road toward civilization.

(2) Katharine Graham, Personal History (1997)

Phil and I flew to California early, five days before the Democratic Convention was to open on July 11. I was already committed to Kennedy. Phil remained loyal to Johnson until he lost the bid for the nomination, but he was entirely realistic, and he, too, admired JFK...

Phil called on Bobby Kennedy and got from him confidential figures on his brother's strength, numbers that showed JFK very close to the number of votes needed to win the nomination close enough so that the Pennsylvania delegation, or a big chunk of it, could put him over. On Monday, Pennsylvania caucused and announced that the state delegation would give sixty-four of its eighty-one votes to Kennedy, which made Phil and the Post reporters write that it would be Kennedy on the first ballot.

At that point, Phil got together with Joe Alsop to discuss the merits of Lyndon Johnson as Kennedy's running mate. Joe persuaded Phil to accompany him to urge Kennedy to offer the vice-presidency to Johnson. Joe had all the secret passwords, and the two men got through to Evelyn Lincoln, Kennedy's secretary, in a room next to his dreary double bedroom and living room. They took a seat on one of the beds and nervously talked out who would say what, while they observed what Joe termed "the antechambers of history." Joe decided he would introduce the subject and Phil should make the pitch.

When they were then taken to the living room to see JFK, Joe opened with, "We've come to talk to you about the vice-presidency. Something may happen to you, and Symington is far too shallow a puddle for the United States to dive into. Furthermore, what are you going to do about Lyndon Johnson? He's much too big a man to leave up in the Senate." Then Phil spoke "shrewdly and eloquently," according to Joe - pointing out all the obvious things that Johnson could add to the ticket and noting that not having Johnson on the ticket would certainly be trouble.

Kennedy immediately agreed, "so immediately as to leave me doubting the easy triumph," Phil noted in a memo afterwards. "So I restated the matter urging him not to count on Johnson's turning it down, but to offer the VPship so persuasively as to win Johnson over." Kennedy was decisive in saying that was his intention, pointing out that Johnson could help not only in the South but elsewhere in the country.

Phil told the Post's reporters they could write that "the word in L.A. is that Kennedy will offer the Vice-Presidency to Lyndon Johnson."

(3) Michael Hasty, Secret Admirers: The Bushes and the Washington Post (5th February , 2004)

In an article published by the media watchdog group, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), Henwood traced the Washington Post's Establishment connections to Eugene Meyer, who took control of the Post in 1933. Meyer transferred ownership to his daughter Katherine and her husband, Philip Graham, after World War II, when he was appointed by Harry S. Truman to serve as the first president of the World Bank. Meyer had been "a Wall Street banker, director of President Wilson's War Finance Corporation, a governor of the Federal Reserve System, and director of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation," Henwood wrote.

Philip Graham, Meyer's successor, had been in military intelligence during the war. When he became the Post's publisher, he continued to have close contact with his fellow upper-class intelligence veterans - now making policy at the newly formed CIA - and actively promoted the CIA's goals in his newspaper. The incestuous relationship between the Post and the intelligence community even extended to its hiring practices. Watergate-era editor Ben Bradlee also had an intelligence background; and before he became a journalist, reporter Bob Woodward was an officer in Naval Intelligence. In a 1977 article in Rolling Stone magazine about CIA influence in American media, Woodward's partner, Carl Bernstein, quoted this from a CIA official: "It was widely known that Phil Graham was somebody you could get help from." Graham has been identified by some investigators as the main contact in Project Mockingbird, the CIA program to infiltrate domestic American media. In her autobiography, Katherine Graham described how her husband worked overtime at the Post during the Bay of Pigs operation to protect the reputations of his friends from Yale who had organized the ill-fated venture.

After Graham committed suicide, and his widow Katherine assumed the role of publisher, she continued her husband's policies of supporting the efforts of the intelligence community in advancing the foreign policy and economic agenda of the nation's ruling elites. In a retrospective column written after her own death last year, FAIR analyst Norman Solomon wrote, "Her newspaper mainly functioned as a helpmate to the war-makers in the White House, State Department and Pentagon." It accomplished this function (and continues to do so) using all the classic propaganda techniques of evasion, confusion, misdirection, targeted emphasis, disinformation, secrecy, omission of important facts, and selective leaks.

Graham herself rationalized this policy in a speech she gave at CIA headquarters in 1988. "We live in a dirty and dangerous world," she said. "There are some things the general public does not need to know and shouldn't. I believe democracy flourishes when the government can take legitimate steps to keep its secrets and when the press can decide whether to print what it knows."

(4) Doug Henwood, The Washington Post: The Establishment's Paper (January, 1990)

After World War II, when Harry Truman named this lifelong Republican as first president of the World Bank, Meyer made his son-in-law, Philip L. Graham, publisher of the paper. Meyer stayed at the Bank for only six months and returned to the Post as its chairman. But with Phil Graham in charge, there was little for Meyer to do. He transferred ownership to Philip and Katharine Graham, and retired.

Phil Graham maintained Meyer's intimacy with power. Like many members of his class and generation, his postwar view was shaped by his work in wartime intelligence; a classic Cold War liberal, he was uncomfortable with McCarthy, but quite friendly with the personnel and policies of the CIA. He saw the role of the press as mobilizing public assent for policies made by his Washington neighbors; the public deserved to know only what the inner circle deemed proper. According to Howard Bray's Pillars of the Post, Graham and other top Posters knew details of several covert operations - including advance knowledge of the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion - which they chose not to share with their readers.

When the manic-depressive Graham shot himself in 1963, the paper passed to his widow, Katharine. Though out of her depth at first, her instincts were safely establishmentarian. According to Deborah Davis' biography, Katharine the Great, Mrs. Graham was scandalized by the cultural and political revolutions of the 1960s, and wept when LBJ fused to run for reelection in 1968. (After Graham asserted that the book as "fantasy," Harcourt Brace Jovanovich pulled 20,000 copies of Katharine the Great in 1979. The book as re-issued by National Press in 87.)

The Post was one of the last major papers to turn against the Vietnam War. Even today, it hews to a hard foreign policy line--usually to the right of The New York Times, a paper not known or having transcended the Cold War.

There was Watergate, of course, that model of aggressive reporting ed by the Post. But even here, Graham's Post was doing the establishment's work. As Graham herself said, the investigation couldn't have succeeded without the cooperation of people inside the government willing to talk to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

These talkers may well have included the CIA; it's widely suspected that Deep Throat was an Agency man (or men). Davis argues that Post editor Ben Bradlee knew Deep Throat, and may even have set him up with Woodward. She produces evidence that in the early 1950s, Bradlee crafted propaganda for the CIA on the Rosenberg case for European consumption. Bradlee denies working "for" the CIA, though he admits having worked for the U.S. Information Agency - perhaps distinction without a difference.

In any case, it's clear that a major portion of the establishment wanted Nixon out. Having accomplished this, there was little taste for further crusading. Nixon had denounced the Post as "Communist" during the 1950s. Graham offered her support to Nixon upon his election in 1968, but he snubbed her, even directing his allies to challenge the Post Co.'s TV license in Florida a few ears later. The Reagans were a different story - for one thing, Ron's crowd knew that seduction was a better way to get good press than hostility. According to Nancy Reagan's memoirs, Graham welcomed Ron and Nancy to her Georgetown house in 1981 with a kiss. During the darkest days of Iran-Contra, Graham and Post editorial page editor Meg GreenfieId - lunch and phone companions to Nancy throughout the Reagan years - offered the First Lady frequent expressions of sympathy. Graham and the establishment never got far from the Gipper.

(5) Carl Bernstein, CIA and the Media, Rolling Stone Magazine (20th October, 1977)

In 1953, Joseph Alsop, then one of America’s leading syndicated columnists, went to the Philippines to cover an election. He did not go because he was asked to do so by his syndicate. He did not go because he was asked to do so by the newspapers that printed his column. He went at the request of the CIA.

Alsop is one of more than 400 American journalists who in the past twenty-five years have secretly carried out assignments for the Central Intelligence Agency, according to documents on file at CIA headquarters. Some of these journalists’ relationships with the Agency were tacit; some were explicit. There was cooperation, accommodation and overlap. Journalists provided a full range of clandestine services - from simple intelligence gathering to serving as go-betweens with spies in Communist countries. Reporters shared their notebooks with the CIA. Editors shared their staffs. Some of the journalists were Pulitzer Prize winners, distinguished reporters who considered themselves ambassadors-without-portfolio for their country. Most were less exalted: foreign correspondents who found that their association with the Agency helped their work; stringers and freelancers who were as interested it the derring-do of the spy business as in filing articles, and, the smallest category, full-time CIA employees masquerading as journalists abroad. In many instances, CIA documents show, journalists were engaged to perform tasks for the CIA with the consent of the managements America’s leading news organizations.

(6) Michael Collins Piper, American Free Press (22nd August, 2001)

Under Philip Graham's stewardship, the Post blossomed and its empire expanded, including the purchase of the then-moribund Newsweek magazine and other media properties.

Following the establishment of the CIA in 1947, Graham also forged close ties to the CIA to the point that he was described by author Deborah Davis, as "one of the architects of what became a widespread practice: the use and manipulation of journalists by the CIA"- a CIA project known as Operation Mockingbird.

According to Davis, the CIA link was integral to the Post's rise to power: "Basically the Post grew up by trading information with the intelligence agencies." In short, Graham made the Post into an effective and influential propaganda conduit for the CIA.

Despite all this, there was, by the time of Eugene Meyer's death in 1959, a growing gulf between Graham and his wife and his father-in-law, who was having second thoughts about turning his empire over to Graham.

The Post publisher took a mistress, Robin Webb, whom he set up in a large house in Washington and a farm outside of the city. A heavy drinker who reportedly had manic-depressive tendencies, Graham, in some respects, was his own worst enemy, stridently abusive to his wife, both privately and publicly.

Katharine Graham's biographer, Deborah Davis, has pointed out that Philip Graham had also started rattling the CIA:

He had begun to talk, after his second breakdown, about the CIA's manipulation of journalists. He said it disturbed him. He said it to the CIA... He turned against the newsmen and politicians whose code was mutual trust and, strangely, silence. The word was that Phil Graham could not be trusted. Graham was actually under surveillance by somebody. Davis has noted that one of Graham's assistants "recorded his mutterings on scraps of paper."

There are those, however, who have suggested that Graham's legendary "mental breakdown" that developed over the next several years was more a consequence of the psychiatric treatments to which he was subjected more so than any illness itself. One writer has speculated that Graham may have been the victim of the CIA's now-infamous experiments in the use of mind-altering drugs.

The Graham split was a major social and political upheaval in Washington, considering the immense power of the newspaper and its intimate ties to the CIA-and the plutocratic elite.

In his biography of Graham's friend and Washington Post attorney Edward Bennett Williams, the aforementioned Evan Thomas wrote that: "Georgetown society was quickly split into 'Phil People' and 'Kay People'" and that while "publicly, Williams was a Phil Person.... as [Kay] later discovered, she need not have been fearful."

Graham startled Williams by saying that not only did he plan to divorce Katharine but that he wanted to re-write his own 1957 will and give everything "Kay" stood to inherit to his mistress, Robin Webb-effectively depriving Katharine of her controlling interest in the powerful newspaper.

Although Williams kept putting off Graham's demand for a divorce, the will, as Thomas admitted, "was a trickier matter." Three times in the spring of 1963 Graham re-wrote his original will of 1957. Each of Graham's 1963 revisions reducing his wife's share and expanding the share he intended for his mistress. Ultimately, the last version cut out Katharine Graham altogether.

A nasty fight was looming. Katharine obviously knew something was afoot because, as Deborah Davis reports, Mrs. Graham "told [her own attorney] Clark Clifford that the divorce settlement must assign control of The Washington Post, and all of the Post companies, exclusively to her."

Matters finally came to a head when Philip attended a newspaper publishers convention in Arizona and delivered a blistering speech attacking the CIA and exposing "insider" secrets about official Washington-even to the point of exposing his friend John Kennedy's affair with Mary Meyer, the wife of a top CIA official, Cord Meyer (no relation to Katharine Graham).

At that point, Katharine flew to Phoenix and snatched up her husband who was captured after a struggle, put in a straitjacket and sedated. He was then flown to an exclusive mental clinic in the Washington suburb of Rockville, Md.

On the morning of Aug. 3, 1963, Katharine Graham reportedly told friends that Philip was "better" and coming home.

She drove to the clinic and picked up her husband and drove him to their country home in Virginia. Later that day, while "Kay" was reportedly napping in her second floor room, her husband died of a shotgun blast in a bathtub downstairs.

Although the police report of the incident was never made public, the death was ruled a suicide. Deborah Davis described the aftermath:

During probate, Katharine's lawyer challenged the legality of the last will, and Edward Bennett Williams, wishing to retain the Post account, now testified that Phil had not been of sound mind when he had drawn up Phil's final will for him. As a result, the judge ruled that Phil had died intestate. Williams helped Katharine take control of the Post with no significant legal problems and ensured that the final will, which left The Washington Post to another woman, never entered the public record.

In her critical biography of Mrs. Graham, Davis never once suggested that Philip had been murdered but has said in interviews that "there's some speculation that either [Katharine] arranged for him to be killed or somebody said to her, 'don't worry, we'll take care of it' " and that "there's some speculation that it might have even been Edward Bennett Williams."

Under Katharine Graham's rule, The Washington Post grew more powerful than ever, and in 1974 played the pivotal role in the destruction of Richard Nixon who was evidently perceived as a danger to the CIA and to the plutocratic elite.

In her book, Katharine the Great-which Mrs. Graham worked hard to suppress-Deborah Davis perhaps provided the real key to Watergate, charging that the Post's famed Watergate source-"Deep Throat"-was almost certainly Richard Ober, the right-hand man of James Angleton, the CIA's counterintelligence chief and longtime liaison to Israel's Mossad.

Miss Davis revealed that Ober was in charge of a joint CIA-Israeli counterintelligence desk established by Angleton inside the White House. From this listening post, Ober (at Angleton's direction) provided inside information to the Post about Watergate that helped bring down the Nixon administration.

All told, considering the record of Katharine Graham and her Washington Post empire, Washington humorist Art Buchwald probably wasn't far off from the truth when he told the Washington elite who gathered for Mrs. Graham's 70th birthday: "There's one word that brings us all together here tonight. And that word is fear."

(7) Deborah Davis, interviewed by Kenn Thomas of Steamshovel Press (1992)

Kenn Thomas: Before we get too far from Phil Graham, I'd like to talk a little bit more about his suicide. Getting back to the article that Leary wrote, he seemed to suggest that there was a reason to believe that it could have been something more than suicide, that there's no indication or public record that Graham wasn't done in. And that the "suicide" happened shortly after this public event where Graham was talking about the JFK/Mary Meyer liaison. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Deborah Davis: Phil died in 1963 and it's now 1992. There's still continuing speculation, 29 years later that he was murdered. In my book, I wrote it as a suicide because that's the way it's been represented and I didn't have any independent knowledge of anything else. If I were doing it today, or if I ever do another edition, I will probably expand on that and spend some time investigating it and finding out whether there is any evidence that it was murder. There were a couple of reasons why it could have been murder. One is the one you mentioned. The people that were protecting Kennedy might have done it because of he was a manic depressive. He was in and out of institutions and he was very mentally unstable. A lot of that probably had to do with the fact that he married into a wealthy family. He married the boss' daughter and they gave him the newspaper, but they were watching every move he made. So he did not react well to the fact that Katharine Graham's father had owned the Washington Post. He may have been killed for that reason, if he was killed.

He may have been killed because he had a mistress named Robin Webb. By that time he had moved out of Katharine's house and he was living with Robin Webb in another house and he was actually behaving as if they were married. He had dinner parties over there with her and invited various members of the Washington elite over there for dinner parties and making it very clear that this was the woman he preferred to Katharine. And at the same time, he was re-writing his will. He re-wrote his will three times. Edward Bennet Williams was his attorney. Edward Bennet Williams, who is very well-known as a Washington power broker. He recently died, but he was very much involved in this. Each time, he willingly, at Phil's request, wrote a will that gave Katharine less and less of a share of the Washington Post and gave more and more of it to Robin Webb. By the third rewrite she had nothing and Robin Webb had everything. And this was at a time when Katharine had pretty much given up on the marriage and realized that in order to save the newspaper, which she thought of as her family newspaper--her father built that newspaper and she didn't want to let it go to some mistress of her husband's--and she had come to the conclusion that she either had to divorce him and win the paper in a divorce settlement, or she had to have him declared mentally incompetent. Each of these alternatives was very unattractive to her. And so there's some speculation that either she arranged for him to be killed or somebody said to her, "don't worry, we'll take care of it" and there's some speculation that it might have even been Edward Bennet Williams.

She took him out of the sanitarium one weekend and took him out to their farm in Virginia and this was where he blew his brains out with a shotgun. And the police report was never really made public. After my paperback edition was published this fall, I got a call from some woman who claims that she knew for a fact that it was murder. And if I ever do publish another edition, I intend to look into that.