James Friell

James Friell, the son of an actor, was born in Glasgow on 13th March 1912. After leaving school at fourteen, he worked in a solicitor's office and taught himself to be a cartoonist, and had his work published in the Glasgow Evening Times.

Friell studied commercial art at Glasgow School of Art in 1930 and two years later he moved to London where he found work in the advertising department of Kodak. He joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and in February 1936 he joined The Daily Worker and working under the name "Gabriel" became the newspaper's political cartoonist.

During the Second World War he served in the Royal Artillery but was kept under observation as a "subversive". In 1944 he set up The Soldier magazine and worked as a cartoonist, art editor and layout man for the journal. After the war he returned to The Daily Worker.

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Harry Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive".

James Friell argued that the Daily Worker should play its part in condemning Stalinism. He argued the newspaper should take the same approach as the Daily Worker in the United States. The editor, John Gates also encouraged debate on this issue by devoting one page of the newspaper to their readers' views: "The readers thought plenty. The paper received an unprecedented flood of mail, and even more unprecedented, we decided to print all the letters, regardless of viewpoint - a step which the Daily Worker had never taken before. The full page of letters, in our modest eight pages, soon became its liveliest and most popular feature... Readers spoke out as never before, pouring out the anguish of many difficult years."

Friell drew a cartoon that showed two worried people reading the Nikita Khrushchev speech. Behind them loomed two symbolic figures labelled "humanity" and "justice". He added the caption: "Whatever road we take we must never leave them behind." As a fellow worker at the newspaper, Alison Macleod, pointed out in her book, The Death of Uncle Joe (1997): "This brought some furious letters from our readers. One of them called the cartoon the most disgusting example of the non-Marxist, anti-working class outbursts..." Macleod went on to point out that a large number of party members shared Friell's sentiments.

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprisingan estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

Friell condemned John R. Campbell, the editor of the newspaper for supporting the invasion. He told Campbell: "How could the Daily Worker keep talking about a counter-revolution when they have to call in Soviet troops? Can you defend the right of a government to exist with the help of Soviet troops? Gomulka said that a government which has lost the confidence of the people has no right to govern." When Campbell refused to publish a cartoon by Friell on the Hungarian Uprising he left the newspaper.

Over 7,000 members of the Communist Party of Great Britain resigned over what happened in Hungary. This included Peter Fryer, who was in Budapest at the time of the invasion. He later recalled: "The crisis within the British Communist Party, which is now officially admitted to exist, is merely part of the crisis within the entire world Communist movement. The central issue is the elimination of what has come to be known as Stalinism. Stalin is dead, but the men he trained in methods of odious political immorality still control the destinies of States and Communist Parties. The Soviet aggression in Hungary marked the obstinate re-emergence of Stalinism in Soviet policy, and undid much of the good work towards easing international tension that had been done in the preceding three years. By supporting this aggression the leaders of the British Party proved themselves unrepentant Stalinists, hostile in the main to the process of democratisation in Eastern Europe. They must be fought as such."

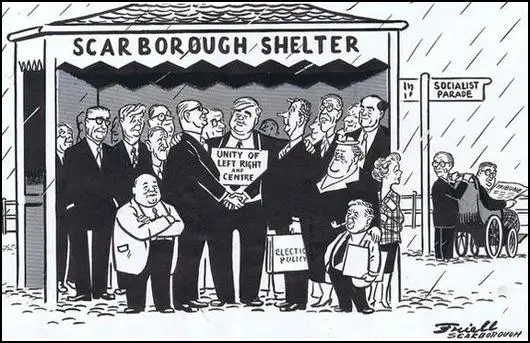

In 1957 Charles Wintour, the editor of the Evening Standard, employed Friell as his political cartoonist. He stayed for five years before becomming a freelance cartoonist. He was also employed by the New Civil Engineer (1972-1988).

James Friell died at his home in Ealing on 4th February 1997.