Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, the only child of Henrik Koestler (1869-1940), Jewish businessman, and Adele Zeiteles (1871–1963), was born in Budapest on 5th September, 1905. Koestler was close to his father but had a difficult relationship with his mother which lasted until her death.

In 1919 the Koestler family fled Hungary after a right-wing coup which deposed the ruling communists, and in 1922 Koestler began studying engineering and physics at the Vienna Technische Hochschule. Koestler became a Jewish nationalist and in 1925 left the university for a kibbutz in Palestine. According to his biographer, Kevin McCarron: "Koestler soon discovered that he was temperamentally unsuited to communal life. He moved to Tel Aviv, where he began to concentrate on journalism, publishing articles in Budapest's Pester Lloyd and in several Zionist papers. In 1927 he was employed by the Ullstein press as their correspondent in the Middle East. Koestler's journalistic work is considered by some to contain his best writing. As his reputation as a writer grew, so too did his disenchantment with Zionism. In 1929 he abruptly left Palestine for Ullstein's Paris office, and in 1930 he moved to Berlin to take up his new position as science editor."

German Communist Party

Koestler was deeply concerned by the emergence of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party and in 1931 joined the German Communist Party. This resulted in him being sacked by Ullstein Verlag. The Communist International sent him to the Soviet Union to write about its first five-year plan. He travelled extensively through the USSR to research for the book but it was rejected by the Soviet authorities for containing too many criticisms of the communist system. Koestler now moved to Paris where he edited the weekly journal, Zukunft . On 22nd June 1935 he married Dorothea Ascher, a Communist Party worker.

Spanish Civil War

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War he was sent by the party to spy on the Nationalist forces. Koestler posed as a right-wing Hungarian journalist working for the News Chronicle, but he came under suspicion and was arrested in Seville in February 1937. He was released the following year in an exchange of prisoners. Upon his release Koestler moved to England, where Victor Gollancz commissioned him to write a book about his experiences. Spanish Testament was published to considerable acclaim in 1937. In 1938 Koestler left the British Communist Party, because of the way Joseph Stalin was dealing with his critics in the Soviet Union.

The Gladiators

In 1939 he published his first novel, The Gladiators (1939), a novel about the Spartacus slave revolt. However, he uses the story of Spartacus as an allegory for the corruption of socialism by Stalin. In September of that year Koestler was arrested in France, wrongly assumed to be a security risk, and was interned as a political prisoner in Le Vernet Concentration Camp until January 1940. His views on totalitarian rule appeared in his second novel, Darkness at Noon (1940). This was followed by The Scum of the Earth (1941), an account of his experiences of internment.

Darkness at Noon

Koestler's biographer, Kevin McCarron, has argued: "Clearly influenced by his experiences in the condemned cells in Spain, Darkness at Noon (1940) describes the arrest and imprisonment of Rubashov, one of the early Bolsheviks, during the purges of 1936. During his numerous interrogations Rubashov reviews his career and his unthinking allegiance to communism. At the end of the novel, as he is beginning to doubt the party, he is shot in the back of the head. The novel was an immediate critical as well as commercial success. The novel became a weapon in the arsenal of the Cold War and remains one of the best-known and most widely read political novels of the twentieth century.

A. J. Ayer became one of Koestler's friends. In his autobiography Part of My Life (1977): Arthur Koestler had already published Darkness at Noon and Scum of the Earth, and I had read and admired them both.... Among other things, Darkness at Noon was the expression of Koestler's own disillusionment with the Communist party. The attraction which Soviet communism held in the middle nineteen-thirties had waned in England as a result of the Moscow trials and the Russian-German pact, but it was renewed with the entry of Russia into the war and increased with the success of Russian arms."

The Second World War

Koestler joined the British Army in 1941, but he had difficulty with military discipline and the following year he went to work for the Ministry of Information film unit and for the BBC, while beginning his third novel, Arrival and Departure (1943). In 1944 Koestler met Mamaine Paget, who was eleven years younger than him. By the end of the war Koestler had returned to his earlier Zionism and was a vocal advocate of the Jewish national cause. After a visit to Palestine he published Thieves in the Night (1946).

The God That Failed

In 1948 Koestler became a British citizen. The following year he published The God That Failed (1949). It included an analysis of faith in politics and religion: "A faith is not acquired by reasoning. One does not fall in love with a woman, or enter the womb of a church, as a result of logical persuasion. Reason may defend an act of faith - but only after the act has been committed, and the man committed to the act. Persuasion may play a part in a man's conversion; but only the part of bringing to its full and conscious climax a process which has been maturing in regions where no persuasion can penetrate. A faith is not acquired; it grows like a tree. Its crown points to the sky; its roots grown downward into the past and are nourished by the dark sap of the ancestral humus."

Mamaine Paget became his second wife on 15th April 1950. They divorced in 1952 and she died aged 38 in 1954. In 1955 he had a daughter, Christine, with Janine Graetez, but he immediately disowned the girl. According to Kevin McCarron: "Koestler was short, handsome, and energetic, and attractive to women. He was, however, sexually predatory all his life - among other affairs he was the co-respondent named in Bertrand Russell's divorce from his third wife, Patricia Spence - and he was capable of treating women brutally.... A chain-smoker and heavy drinker, he could be arrogant, dogmatic, and violent, but he was financially generous, especially to continental intellectuals and refugees, and he was considered a welcoming host, and very lively, often too lively, company."

David Cesarani, the author of Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind (1998), has provided first-hand accounts of his violence towards women. Richard Brooks has argued that "Koestler was a compulsive adulterer who conducted hundreds of affairs throughout his marriages". His official biographer, Michael Scammell, the author of Koestler: The Indispensable Intellectual (2010) agreed with this view and accused him of "chronic promiscuity" and claims that Koestler's lovers included Simone de Beauvoir, Elizabeth Jane Howard and Sonia Brownell, who described him as a "sadist". Scammell quotes a letter written by Koestler where he argues “without an element of initial rape in seduction there is no delight”. However, Scammell raised doubts about an earlier claim made by Michael Foot that Koestler had raped his wife, Jill Craigie.

In 1951 he published his fourth novel, The Age of Longing. From 1952 to 1955 he worked on two volumes of autobiography: Arrival and Departure (1952) and The Invisible Writing (1954). According to one critic: "Lucid, analytical, yet emotional, Koestler depicts himself in his autobiographical writings as both a unique human being and a representative, universal voice of the twentieth century." Other books by Koestler during this period included Reflections on Hanging (1956), The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe (1959) and Hanged By the Neck (1961).

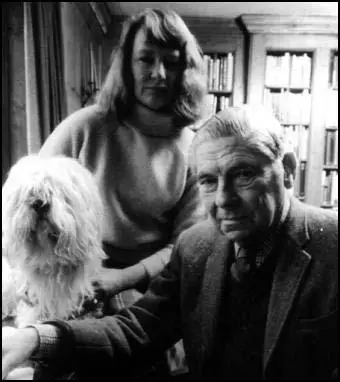

On 8th January 1965, the sixty-year-old, Koestler, married the thirty-seven year old, Cynthia Jefferies, who had been his secretary and occasional lover since 1948. He continued to write and published The Ghost in the Machine (1967), The Case of the Midwife Toad (1971), The Call Girls (1972), The Roots of Coincidence (1972) and Life After Death (1976).

Suicide

In 1976 Koestler was diagnosed as having Parkinson's disease and his health deteriorated over the next seven years, during which he also succumbed to terminal leukaemia. He wrote in his suicide note: "My reasons for deciding to put an end to my life are simple and compelling: Parkinson's Disease and the slow-killing variety of leukaemia (CCI). I kept the latter a secret even from intimate friends to save them distress. After a more or less steady physical decline over the last years, the process has now reached an acute state with added complications which make it advisable to seek self-deliverance now, before I become incapable of making the necessary arrangements... What makes it nevertheless hard to take this final step is the reflection of the pain it is bound to inflict on my surviving friends, above all my wife Cynthia. It is to her that I owe the relative peace and happiness that I enjoyed in the last period of my life - and never before."

Michael Scammell has argued that Koestler had a “sadomasochistic” relationship with his wife and despite being in perfect health agreed to commit suicide with her husband. She wrote in a note: “I fear both death and the act of dying... Double suicide has never appealed to me, but now Arthur’s incurable diseases have reached a stage where there is nothing else to do.” Scammell sees his wish for her to die with him as evidence of his selfishness.

On 3rd March 1983, Arthur and Cynthia Koestler were found dead in their flat at 8 Montpelier Square, Kensington, London. They had killed themselves with a mixture of tuinal and alcohol. Koestler left bequests which totalled almost £1 million to further the study of parapsychology.

Primary Sources

(1) Arthur Koestler, Dialogue With Death (1942)

I left Paris on January 15th (1937), took train to Toulouse and from there flew to Barcelona. I stayed in Barcelona for only one day. The city presented a depressing picture. There was no bread, no milk, no meat to be had, and there were long queues outside the shops. The Anarchists blamed the Catalan Government for the food shortage and organised an intensive campaign of political agitation; the windows of the trams were plastered with their leaflets. The tension in the city was near danger-point. It looked as though Spain were not only to be the stage for the dress-rehearsal of the second world war, but also for the fratricidal struggle within the European Left.

I was glad not to have to write an article on Barcelona. On the 16th I left by the 4 p.m. train for Valencia with Willy Forrest, also of the News Chronicle . His destination was Madrid, mine Malaga.

The train to Valencia was crowded out. Every compartment contained four times as many Militiamen, sitting, lying down or standing, as it was meant to hold. A kindly railway official installed us in a first class carriage and locked the door from the outside so that we should not be disturbed. 'Scarcely had the train started when four Anarchist Militiamen in the corridor began to hammer at the glass door of our compartment. We tried to open it, but could not; we were trapped in our cage. The guard who had the key had completely vanished. We were unable to make ourselves understood through the locked door owing to the noise of the train, and the Militiamen thought that it was out of sheer ill-will that we were not opening it. Forrest and I could not help grinning, which further enraged the Militiamen, and the situation became more dramatic from minute to minute. Half the coach collected outside the glass door to gaze at the two obviously Fascist agents. At length the guard came and unlocked the door and explained the situation, and then ensued a perfect orgy of fraternising and eating, and a dreadful hullabaloo of pushing and shouting and singing.

By dawn the train was six hours behind time. It was going so slowly that the Militiamen jumped from the footboards, picked handfuls of oranges from the trees that grew on the edge of the embankment and clambered back again into the carriage amidst general applause. This form of amusement continued until about midday.

Valencia too disported itself in the brilliant January sunshine with one weeping and one smiling eye. There was a shortage of paper; some of the newspapers were cut down to four pages, three full of the Civil War, the fourth of football championships, bullfights, theatre and film notices. Two days before our arrival a decree had been issued ordering the famous Valencia cabarets to close at nine o'clock in the evening "in view of the gravity of the situation". Of course they all continued to keep open until one o'clock in the morning, with one exception, and that one adhered strictly to the letter of the law. The owner was later unmasked as a rebel supporter and his cabaret was closed down.

(3) Arthur Koestler, Spanish Testament (1938)

My stay in Seville was very instructive and very brief.

My private hobby was tracking down the German airmen; that is to say, the secret imports of 'planes and pilots, which at that time was in full swing, but was not so generally known as it is today. It was the time when European diplomacy was just celebrating its honeymoon with the Non-Intervention Pact. Hitler was denying having despatched aircraft to Spain, and Franco was denying having received them, while there before my very eyes fat, blond German pilots, living proof to the contrary, were consuming vast quantities of Spanish fish, and, monocles clamped into their eyes, reading the "Volkischer Beobachter."

There were four of these gentlemen in the Hotel Cristina in Seville at about lunch time on 28 August 1936. The Cristina is the hotel of which the porter had told me that it was full of German officers and that it was not advisable to go there, because every foreigner was liable to be taken for a spy.

I went there, nevertheless. It was, as I have said, about two o'clock in the afternoon. As I entered the lounge, the four pilots were sitting at a table, drinking sherry. The fish came later.

Their uniforms consisted of the white overall worn by Spanish airmen; on their breasts were two embroidered wings with a small swastika in a circle (a swastika in a circle with wings is the so-called "Emblem of Distinction" of the German National-Socialist Party).

In addition to the four men in uniform one other gentleman was sitting at the table. He was sitting with his back to me; I could not see his face.

I took my place some tables further on. A new face in the lounge of a hotel occupied by officers always creates a stir in times of civil war. I could tell that the five men were discussing me. After some time the fifth man, the one with his back to me, got up and strolled past my table with an air of affected indifference. He had obviously been sent out to reconnoitre.

As he passed my table, I looked up quickly from my paper and hid my face even more quickly behind it again. But it was of no use; the man had recognized me, just as I had recognized him. It was Herr Strindberg, the undistinguished son of the great August Strindberg; he was a Nazi journalist, and war correspondent in Spain for the Ullstein group.

This was the most disagreeable surprise imaginable. I had known the man years previously in Germany at a time when Hitler had been still knocking at the door, and he himself had been a passionate democrat. At that time I had been on the editorial staff of the Ullstein group, and his room had been only three doors from mine. Then Hitler came to power and Strindberg became a Nazi.

We had no further truck with one another but he was perfectly aware of my views and political convictions. He knew me to be an incorrigible Left-wing liberal, and this was quite enough to incrim inate me. My appearance in this haunt of Nazi airmen must have appeared all the more suspect inasmuch as he could not have known that I was in Seville for a newspaper.

He behaved as though he had not recognized me, and I did the same. He returned to his table.

He began to report to his friends in an excited whisper. The five gentlemen put their heads together.

Then followed a strategic manoeuvre: two of the airmen strolled towards the door - obviously to cut off my retreat; the third went to the porter's lodge and telephoned - obviously to the police; the fourth pilot and Strindberg paced up and down the room.

I felt more and more uncomfortable and every moment expected the Guardia Civil to turn up and arrest me. I thought the most sensible thing would be to put an innocent face on the whole thing, and getting up, I shouted across the two intervening tables with (badly) simulated astonishment:

"Hallo, aren't you Strindberg?"

He turned pale and became very embarrassed, for he had not expected such a piece of impudence.

"I beg your pardon, I am talking to these gentlemen," he said.

Had I still had any doubts, this behaviour on his part would in itself have made it patent to me that the fellow had denounced me Well I thought, the only thing that's going to get me out ot this is a little more impudence. I asked him in a very loud voice, and as arrogantly as possible, what reason he had for not shaking hands with me.

He was completely bowled over at this, and literally gasped. At this point his friend, airman number four, joined in the fray. With a stiff little bow he told me his name, von Bernhardt, and demand ed to see my papers.

The little scene was carried on entirely in German.

I asked by what right Herr von Bernhardt, as a foreigner, demanded to see my papers.

Herr von Bernhardt said that as an officer in the Spanish Army he had a right to ask "every suspicious character" for his papers.

Had I not been so agitated, I should have pounced upon this statement as a toothsome morsel. That a man with a swastika on his breast should acknowledge himself in German to be an officer in Franco's army, would have been a positive tit-bit for the Non- Intervention Committee.

I merely said, however, that I was not a "suspicious character, but an accredited correspondent of the London "News Chronicle," that Captain Bolin would confirm this, and that I refused to show my papers.

When Strindberg heard me mention the "News Chronicle he did something that was quite out of place: he began to scratch his head Herr von Bernhardt too grew uncomfortable at the turn ot events and sounded a retreat. We went on arguing for a while, until Captain Bolin entered the hotel. I hastened up to him and demanded that the others should apologise to me, thinking to myself that attack was the best defence and that I must manage at all costs to prevent Strindberg from having his say. Bolin was astonished at the scene and indignantly declared that he refused to have anything to do with the whole stupid business, and that in time of civil war he didn't give a damn whether two people shook hands or not.

(3) Arthur Koestler, Spanish Testament (1938)

So it is all over. Malaga has surrendered.

And I remember Colonel Villalba's last statement before he stepped into his car: "The situation is a critical one, but Malaga will put up a good fight."

Malaga did not put up a good fight.

The city was betrayed by its leaders - deserted, delivered up to the slaughter. The rebel cruisers bombarded us and the ships of the Republic did not come. The rebel 'planes sowed panic and destruction, and the 'planes of the Republic did not come. The rebels had artillery, armoured cars and tanks, and the arms and war material of the Republic did not come. The rebels advanced from all directions and the bridge on the only road connecting Malaga with the Republic had been broken for four months. The rebels maintained an iron discipline and machine-gunned their troops into battle, while the defenders of Malaga had no disci pline, no leaders, and no certainty that the Republic was backing them up. Italians, Moors and Foreign Legionaries fought with the professional bravery of mercenaries against the people in a cause that was not theirs; and the soldiers of the people, who were fight ing for a cause that was their own, turned tail and ran away.

It would be far too glib to explain away the catastrophes of Badajoz, Toledo and Malaga simply by pointing to the enemy's superiority in war material. Nor does the fact of the treachery and desertion of the local leaders of Malaga alone suffice as an explanation. The city was in the charge of men who proved incompetent - yet no less great is the responsibility of the Central Government of Valencia, which sent neither ships nor 'planes nor war material to Malaga, and did not have the sense to replace incompetent lead ers by good ones. With Malaga Largo Caballero's Government completed the chapter of their mistakes and errors of judgment; they had to go. But a whole string of those who bear the responsi bility for the unfortunate course of the Civil War up till now (I am writing these lines in September, 1937) still remain. This is one of those things that fills the friends of Spanish democracy with the gravest concern.

(4) Arthur Koestler, Dialogue With Death (1942)

The sudden opening of his cell door at a time other than the regular feeding time is always a shock to a prisoner. For the first few moments I was thrown into such confusion by the sight of the three uniformed figures that I murmured some idiotic kind of apology at being unable to offer the young lady anything better to sit on than my iron bedstead. But she only smiled - a rather charming smile it seemed to me - and asked if my name was Koestler, and whether I spoke English. To both questions I replied in the affirmative.

Then she asked me whether I was a Communist. To this I had to reply in the negative.

"But you are a Red, aren't you?"

I said that I was in sympathy with the Valencia Government, but did not belong to any party.

The young lady asked me whether I was aware what would be the consequence of my activities.

I said that I was not.

"Well," she said, "it means death."

She spoke with an American twang, drawling out the vowel sound in 'death' so that it sounded like 'dea-ea-h-th', and watched the effect.

I asked why.

Because, she said, I was supposed to be a spy.

I said that I was not, and that I had never heard of a spy who signed articles and a book attacking one side in a war and then afterwards went into the territory of that side with his passport in his pocket.

She said that the authorities would investigate that point, but that in the meantime General Franco had been asked by the News Chronicle and by Mr. Hearst of New York to spare my life; that she happened to be the correspondent of the Hearst Press in Spain, and that General Franco had said that I would be condemned to death, but that he might possibly grant a commutation of my sentence.

I asked her what exactly she meant by a commutation.

"Well, life-long imprisonment. But there is always hope of an amnesty, you know," she said, with her charming smile.

A perfect cyclone of thoughts rushed through my head. First of all I had had a set of dirty postcards to thank for my life, and now here was Randolph Hearst himself as my second saviour - my guardian angels seemed to be a somewhat poor lot. And then, what was the significance of that fateful phrase, "might possibly grant a commutation"?

But I had not much time for reflection. The young lady on my bed asked me in charming conversational tones if I would like to make a statement to her paper with regard to my feelings towards General Franco.

I was pretty bewildered by all tills, but not so bewildered as not to perceive the fateful connection between this question and that "might possibly" of General Franco's. This was something like a Biblical temptation, although Satan was presenting himself in the smiling mask of a young woman journalist; and at that moment - after all those days of waiting for torture and death - I had not the moral strength to resist.

So I said that although I did not know Franco personally I had a feeling that he must be a man of humanitarian outlook whom I could trust implicitly. The young lady wrote this down, seemingly very pleased, and asked me to sign it.

I took the pen, and then I realised that I was about to sign my own moral death sentence, and that this sentence no one could commute. So I crossed out what she had written and dictated another statement, which ran:

"I do not know General Franco personally, nor he me; and so, if he grants me a commutation of my sentence I can only suppose that it is mainly from political considerations. Nevertheless, I could not but be personally grateful to him, just as any man is grateful to another who saves his life. But I believe in the Socialist conception of the future of humanity, and shall never cease to believe in it."

This statement I signed.

The temptation of Satan had been resisted, and I patted myself inwardly on the back and rejoiced at having a clear head once more. I had good need of it too, for Miss Helena's next question was what did I actually mean by a "Socialist conception of the future of humanity"?

This question called for an academic dissertation, and I was about to launch forth on one. But the three Phalangists were hardly a sympathetic audience for my passionate rhetorical efforts. The young lady cut me short and suggested the lapidary formula :

"Believes in Socialism to give workers chance."

She said Americans understood things the better the more briefly they were put.

(5) A. J. Ayer, Part of My Life (1977)

Arthur Koestler had already published Darkness at Noon and Scum of the Earth, and I had read and admired them both. He had no reason to distinguish me from any other Guards Officer and seemed a little taken aback when we fell into an argument. I was the first to leave, and as I made my way downstairs I heard him ask Paul rather sharply who I was. Since then our relations have been chequered. There have been times when we have been good friends, but longer periods of estrangement in which, on my side, at least, our intellectual differences have been emotionally tinged. This extends to my judgement of him as a writer. I think very highly of his autobiographical books and continue greatly to admire the psychological and political insight of Darkness at Noon. At the same time, I cannot help wishing that he would leave philosophy alone.

Among other things, Darkness at Noon was the expression of Koestler's own disillusionment with the Communist party. The attraction which Soviet communism held in the middle nineteen-thirties had waned in England as a result of the Moscow trials and the Russian-German pact, but it was renewed with the entry of Russia into the war and increased with the success of Russian arms.

(6) Arthur Koestler, suicide note (1st March, 1983)

To whom it may concern. The purpose of this note is to make it unmistakably clear that I intend to commit suicide by taking an overdose of drugs without the knowledge or aid of any other person. The drugs have been legally obtained and hoarded over a considerable period. Trying to commit suicide is a gamble the outcome of which will be known to the gambler only if the attempt fails, but not if it succeeds. Should this attempt fail and I survive it in a physically or mentally impaired state, in which I can no longer control what is done to me, or communicate my wishes, I hereby request that I be allowed to die in my own home and not be resuscitated or kept alive by artificial means. I further request that my wife, or a physician, or any friend present, should invoke habeas corpus against any attempt to remove me forcibly from my house to hospital.

My reasons for deciding to put an end to my life are simple and compelling: Parkinson's Disease and the slow-killing variety of leukaemia (CCI). I kept the latter a secret even from intimate friends to save them distress. After a more or less steady physical decline over the last years, the process has now reached an acute state with added complications which make it advisable to seek self-deliverance now, before I become incapable of making the necessary arrangements.

I wish my friends to know that I am leaving their company in a peaceful frame of mind, with some timid hopes for a de-personalised after-life beyond due confines of space, time and matter and beyond the limits of our comprehension. This "oceanic feeling" has often sustained me at difficult moments, and does so now, while I am writing this.

What makes it nevertheless hard to take this final step is the reflection of the pain it is bound to inflict on my surviving friends, above all my wife Cynthia. It is to her that I owe the relative peace and happiness that I enjoyed in the last period of my life - and never before...

Since the above was written in June 1982, my wife decided that after thirty-four years of working together she could not face life after my death.

I fear both death and the act of dying that lies ahead of us. I should have liked to finish my account of working for Arthur – a story which began when our paths happened to cross in 1949. However, I cannot live without Arthur, despite certain inner resources.

Double suicide has never appealed to me, but now Arthur's incurable diseases have reached a stage where there is nothing else to do.

(7) Cynthia Koestler, suicide note (1st March, 1983)

I fear both death and the act of dying that lies ahead of us. I should have liked to finish my account of working for Arthur – a story which began when our paths happened to cross in 1949. However, I cannot live without Arthur, despite certain inner resources. Double suicide has never appealed to me, but now Arthur's incurable diseases have reached a stage where there is nothing else to do.

(8) Richard Brooks, The Sunday Times (20th December, 2009)

Koestler, more famous in his lifetime for his disillusionment with communism, was known to be unfaithful with several women. The full extent of his often brutal philandering, however, now threatens to overshadow his reputation as one of the foremost writers and thinkers of the 20th century.

Michael Scammell, the biographer, describes the Hungarian-born Koestler as “a magnet for women”, and says his life was marked by “chronic promiscuity”.

The book, to be published in February by Faber and Faber, does, however, dispute one of the most extreme claims made in recent years about Koestler - that he raped Jill Craigie, the late wife of the former Labour leader Michael Foot.

Scammell describes the allegation as based on a “dressed up” account of when Koestler and Craigie went on a pub crawl together...

While Scammell commends Koestler’s anti-communism and intellect, the author’s sexual behaviour does him no favours. He was married three times, the last time to Cynthia, who joined him in a double suicide in London in 1983, and he was compulsively unfaithful.

Few of the women Scammell has interviewed over the past 25 years, or whose correspondence he has read, is flattering about Koestler....

David Cesarani, professor of history at Royal Holloway college in Egham, Surrey, who made the Craigie rape claim in a 1998 book, said: “Scammell has come up with much more damning stuff about Koestler’s women than I did. If Scammell’s book is the case for the defence, God help Koestler’s reputation.”

Scammell argues that Koestler’s own diary entry for the day, which came after Craigie’s marriage to Foot in 1949, simply refers to a pub crawl on Hampstead Heath, north London, with her.

“He would usually proudly write about his sexual conquests,” says the biographer. “He was drunk with Craigie but he behaved like thousands of men of his generation,” writes Scammell, implying that if the pair did have sex, it would not have been seen as rape. At the time, men pressing themselves on women was seen as less unacceptable than today.