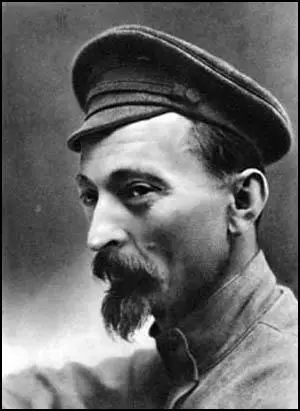

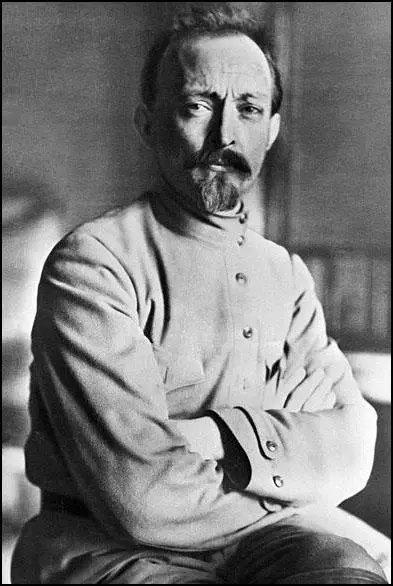

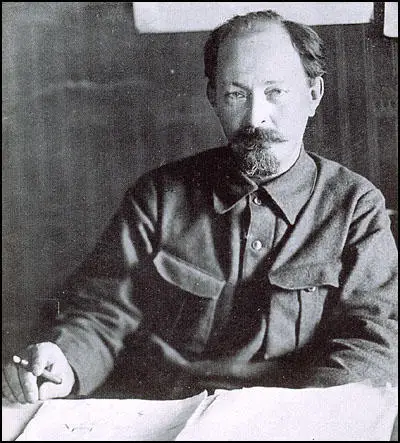

Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Dzerzhinsky, the son of a Polish landowner, was born in Vilno in 1877. He joined the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party and helped to organize factory workers into trade unions.

Dzerzhinsky was arrested in 1897 but managed to escape from Siberia two years later. He went to Warsaw where he joined the Social Democratic Party of Poland (SDPP) that had been formed by Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches in 1893. Karl Radek was a fellow leader of the SDPP: "Dzerzhinskycame to be the most beloved of all the Polish leaders. Tall, well built, with ardent eyes, quick, passionate speech, thus I first met him in the autumn of 1903. He won the love and esteem not only of the older workers, but also of the youth then coming into the movement. In their eyes he was surrounded by a halo by reason of his terms in prison and exile and his reputation as Party organizer. His opinion was valued not only by Rosa but even by veteran Tyszka who had great organizational experience and who combined sound Marxian scholarship with wonderful political sensitivity. On all practical questions of the movement Joseph’s opinion was almost decisive. How did he obtain this authority? In fact, what was the personal origin of this energetic revolutionist, so strict towards himself and towards everybody else too, this man able to inspire and lead them all?"

Dzerzhinsky was arrested again and spent another nine years in Siberia until being released as a result of the political amnesty that followed the February Revolution and played an active role in the October Revolution. In December, 1917, Lenin appointed Dzerzhinsky as Commissar for Internal Affairs and head of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (Cheka). As Dzerzhinsky later commented: "In the October Revolution, I was a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee, and then I was entrusted with the task of organizing the Extraordinary Commission for the Struggle against Sabotage and Counterrevolution I was appointed its Chairman, holding at the same time the post of Commissar for Internal Affairs." Dzerzhinsky selected Yakov Peters as his deputy. Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972) has argued: "He (Dzerzhinsky) was ruthless, cold, clear-headed, gifted with organisational talents and insisted from the start that he must have full powers and not be subject to any supervision. Such was the regard Lenin had for the man that he was given these powers without reservation. Dzerzhinsky had studied the techniques of both espionage and counter-espionage and he knew that the first task of his Secret Service must be to protect the country from the forces of counter-revolution." On one occasion Dzerzhinsky and Yakov Peters took diplomat Robert Bruce Lockhart and journalist, Arthur Ransome, on a raid of 26 Anarchist strongholds in Moscow. Lockhart later recorded: " The Anarchists had appropriated the finest houses in Moscow... The filth was indescribable. Broken bottles littered the floors; the magnificent ceilings were perforated with bullet holes. Wine stains and human excrement blotched the Aubusson carpets. Priceless pictures had been slashed to strips. The dead still lay where they had fallen. They included officers in guard's uniforms, students - young boys of twenty - and men who belonged obviously to the criminal class and whom the revolution had released from prison. In the luxurious drawing room of the House Gracheva the Anarchists had been surprised in the middle of an orgy. The long table which had supported the feast had been overturned, and broken plates, glasses, champagne bottles, made unsavoury islands in a pool of blood and spilt wine. On the floor lay a young woman, face downwards. Yakov Peters turned her over. Her hair was dishevelled. She had been shot through the neck and the blood had congealed in a sinister purple clump. She could not have been more than twenty." According to Lockhart, Peters shrugged his shoulders. "Prostitutka," he said, "Perhaps it is for the best." In his first address as chief of the Soviet secret police Dzerzhinsky declared: "This is no time for speech-making. Our Revolution is in serious danger. We tolerate too good-naturedly what is transpiring around us. The forces of our enemies are organizing. The counter-revolutionaries are at work and are organizing their groups in various sections of the country. The enemy is encamped in Petrograd, at our very hearth! We have indisputable evidence of this and we must send to this front the most stern, energetic, hearty and loyal comrades who are ready to do all to defend the attainments of our Revolution. Do not think that I am on the look-out for forms of revolutionary justice. We have no need for justice now. Now we have need of a battle to the death! I propose, I demand the initiation of the Revolutionary sword which will put an end to all counter-revolutionists. We must act not tomorrow, but today, at once!" One of Dzerzhinsky's fellow revolutionaries, Victor Serge, later argued: "I believe that the formation of the Chekas was one of the gravest and most impermissible errors that the Bolshevik leaders committed in 1918 when plots, blockades, and interventions made them lose their heads. All evidence indicates that revolutionary tribunals, functioning in the light of day and admitting the right of defence, would have attained the same efficiency with far less abuse and depravity. Was it necessary to revert to the procedures of the Inquisition?" Robert Bruce Lockhart, a British diplomat in Russia, met Dzerzhinsky during this period. "A man of correct manners and quiet speech, but without a ray of humour in his character. The most remarkable thing about him was his eyes. Deeply sunk, they blazed with a steady fire of fanaticism. They never twitched. His eyelids seemed paralysed." Dzerzhinsky explained in July 1918: "We stand for organized terror - this should be frankly admitted. Terror is an absolute necessity during times of revolution. Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government and of the new order of life. We judge quickly. In most cases only a day passes between the apprehension of the criminal and his sentence. When confronted with evidence criminals in almost every case confess; and what argument can have greater weight than a criminal's own confession." David Shub, a former member of the Mensheviks, reported: "In his little room Dzerzhinsky was constantly sharpening the weapon of the Soviet dictatorship. To Dzerzhinsky was brought the mass of undigested rumours from all parts of Petrograd. With the aid of picked squads of Chekists, Dzerzhinsky undertook to purge the city. At night his men moved from the dark streets into apartment houses; towards dawn they returned with i their haul. Few if any challenged the authority of these men. Their password was enough: Cheka, the all-powerful political police. Little time was wasted sifting evidence and classifying people rounded up in these night raids. Woe to him who did not disarm all suspicion at once. The prisoners were generally hustled to the old police station not far from the Winter Palace. Here, with or without perfunctory interrogation, they were stood up against the courtyard wall and shot. The staccato sounds of death were muffled by the roar of truck motors kept going for the purpose." George Seldes, an American journalist working in Russia, wrote: "Because of Cheka, freedom has ceased to exist in Russia. There is no democracy. It is not wanted. Only American apologists for the Soviets have ever pretended there was democracy in Russia.... Freedom, liberty, justice as we know it, democracy, all the fundamental human rights for which the world has been fighting for civilized centuries, have been abolished in Russia in order that the communist experiment might be made. They have been kept suppressed by the Cheka. The Cheka is the instrument of militant Communism. It is a great success. The terror is in the mind and marrow of the present generation and nothing but generations of freedom and liberty will ever root it out." On 17th August, 1918, Moisei Uritsky, the Commissar for Internal Affairs in the Northern Region, was assassinated by Leonid Kannegisser, a young military cadet. Anatoly Lunacharsky commented: "They killed him. They struck us a truly well-aimed blow. They picked out one of the most gifted and powerful of their enemies, one of the most gifted and powerful champions of the working class." The Soviet press published allegations that Uritsky had been killed because he was unravelling "the threads of an English conspiracy in Petrograd". Despite these claims, Robert Bruce Lockhart, Head of Special Mission to the Soviet Government with the rank of acting British Consul-General in Moscow, continued with his plans to overthrow the Bolshevik government. He had a meeting with a senior intelligence agent based in the French Embassy. He was convinced that Colonel Eduard Berzin was genuine in his desire to overthrow the Bolsheviks and was willing to put up some of the money needed: "The Letts are Bolshevik servants because they have no other resort. They are foreign hirelings. Foreign hirelings serve for money. They are at the disposal of the highest bidder." George Alexander Hill, Sidney Reilly and Ernest Boyce were brought into the conspiracy. Over the next week Hill, Reilly and Boyce were having regular meetings with Berzin, where they planned the overthrow of the Bolsheviks. During this period they handed over 1,200,000 rubles. Some of this money came from the American and French governments. Unknown to MI6 this money was immediately handed over to Felix Dzerzhinsky. So also were the details of the British conspiracy. Berzin told the agents that his troops had been to assigned to guard the theatre where the Soviet Central Executive Committee was to met. A plan was devised to arrest Lenin and Leon Trotsky at the meeting was to take place on 28th August, 1918. Robin Bruce Lockhart, the author of Reilly: Ace of Spies (1992) has argued: "Reilly's grand plan was to arrest all the Red leaders in one swoop on August 28th when a meeting of the Soviet Central Executive Committee was due to be held. Rather than execute them, Reilly intended to de-bag the Bolshevik hierarchy and with Lenin and Trotsky in front, to march them through the streets of Moscow bereft of trousers and underpants, shirt-tails flying in the breeze. They would then be imprisoned. Reilly maintained that it was better to destroy their power by ridicule than to make martyrs of the Bolshevik leaders by shooting them." Reilly later recalled: "At a given signal, the soldiers were to close the doors and cover all the people in the Theatre with their rifles, while a selected detachment was to secure the persons of Lenin and Trotsky... In case there was any hitch in the proceedings, in case the Soviets showed fight or the Letts proved nervous... the other conspirators and myself would carry grenades in our place of concealment behind the curtains." However, at the last moment, the Soviet Central Executive Committee meeting was postponed until 6th September. On 31st August 1918, Dora Kaplan attempted to assassinate Lenin. It was claimed that this was part of the British conspiracy to overthrow the Bolshevik government and orders were issued by Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka, to round up the agents based in British Embassy in Petrograd. The naval attaché, Francis Cromie was killed resisting arrest. According to Robin Bruce Lockhart: "The gallant Cromie had resisted to the last; with a Browning in each hand he had killed a commissar and wounded several Cheka thugs, before falling himself riddled with Red bullets. Kicked and trampled on, his body was thrown out of the second floor window." Robert Bruce Lockhart was woken by a rough voice ordering him out of bed in Moscow. "As I opened my eyes, I looked up into the steely barrel of a revolver. Some ten men were in my room." As he dressed "the main body of the invaders began to ransack the flat for compromising documents." Lockhart was taken to Lubyanka Prison. He later recalled: "My prison here consists of a small hall, a sitting-room, a diminutive bedroom, a bathroom and a small dressing-room, which I use for my food. The rooms open on both sides on to corridors so that there is no fresh air. I have one sentry one side and two on the other. They are changed every four hours and as each changes, has to come in to see if I am there. This results in my being woken up at twelve and four in the middle of the night." Lockhart was eventually interrogated by Yakov Peters, Dzerzhinsky's deputy at Cheka. "At the table, with a revolver lying beside the writing pad, was a man, dressed in black trousers and a white Russian shirt... His lips were tightly compressed and, as I entered the room, his eyes fixed me with a steely stare." Lockhart added that his face was sallow and sickly, as he never saw the light of day. Lockhart, who was an accredited diplomat, complained about his treatment. Peters ignored these comments and asked him if he knew Dora Kaplan. When he explained that he had never heard of her, Peters asked him about the whereabouts of Sidney Reilly. Lockhart now knew that Cheka had discovered the British plot against Lenin. This was confirmed when he produced the letter Lockhart had personally written for Colonel Eduard Berzin as an introduction to General Frederick Cuthbert Poole, the head of the British invasion force in Northern Russia. Despite the evidence he had against him, Peters decided to release Lockhart. Joseph Stalin, who was in Tsaritsyn at the time of the assassination attempt on Lenin, sent a telegram to Yakov Sverdlov suggesting: "having learned about the wicked attempt of capitalist hirelings on the life of the greatest revolutionary, the tested leader and teacher of the proletariat, Comrade Lenin, answer this base attack from ambush with the organization of open and systematic mass terror against the bourgeoisie and its agents." Dzerzhinsky, on the advice of Stalin, instigated the Red Terror. The Bolshevik newspaper, Krasnaya Gazeta, reported on 1st September, 1918: "We will turn our hearts into steel, which we will temper in the fire of suffering and the blood of fighters for freedom. We will make our hearts cruel, hard, and immovable, so that no mercy will enter them, and so that they will not quiver at the sight of a sea of enemy blood. We will let loose the floodgates of that sea. Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies in scores of hundreds. Let them be thousands; let them drown themselves in their own blood. For the blood of Lenin and Uritsky, Zinovief and Volodarski, let there be floods of the blood of the bourgeois - more blood, as much as possible." It is estimated that in the next few months 800 socialists were arrested and shot without trial. Dzerzhinsky reported "Our enemies are now suppressed and are in the kingdom of the shadows." Lev Kamenev admitted: "Not a single measure of the Soviet government could have been put through without the help of the Cheka. It is the best example of communist discipline." Lenin defended the work of Felix Dzerzhinsky and Yakov Peters by publicly stating: "What surprises me about the howls over the Cheka's mistakes is the inability to take a large view of the question. We have people who seize on particular mistakes by the Cheka, sob and fuss over them... When I consider the Cheka's activity and compare it with these attacks, I say this is narrow-minded, idle talk which is worth nothing... When we are reproached with cruelty, we wonder how people can forget the most elementary Marxism.... The important thing for us to remember is that the Chekas are directly carrying out the dictatorship of the proletariat, and in this respect their role is invaluable." On 2nd September, 1918, Bolshevik newspapers splashed on their front pages the discovery of an Anglo-French conspiracy that involved undercover agents and diplomats. One newspaper insisted that "Anglo-French capitalists, through hired assassins, organised terrorist attempts on representatives of the Soviet." These conspirators were accused of being involved in the murder of Moisei Uritsky and the attempted assassination of Lenin. Lockhart and Reilly were both named in these reports. "Lockhart entered into personal contact with the commander of a large Lettish unit... should the plot succeed, Lockhart promised in the name of the Allies immediate restoration of a free Latvia." An edition of Pravda declared that Lockhart was the main organiser of the plot and was labelled as "a murderer and conspirator against the Russian Soviet government". The newspaper then went on to argue: "Lockhart... was a diplomatic representative organising murder and rebellion on the territory of the country where he is representative. This bandit in dinner jacket and gloves tries to hide like a cat at large, under the shelter of international law and ethics. No, Mr Lockhart, this will not save you. The workmen and the poorer peasants of Russia are not idiots enough to defend murderers, robbers and highwaymen." The following day Robert Bruce Lockhart was arrested and charged with assassination, attempted murder and planning a coup d'état. All three crimes carried the death sentence. The couriers used by British agents were also arrested. Lockhart's mistress, Maria Zakrveskia, who had nothing to do with the conspiracy, was also taken into custody. Xenophon Kalamatiano, who was working for the American Secret Service, was also arrested. Hidden in his cane was a secret cipher, spy reports and a coded list of thirty-two spies. However, Sidney Reilly, George Alexander Hill, and Paul Dukes had all escaped capture and had successfully gone undercover. Yakov Peters interrogated Lockhart for several days. Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette (2013) has pointed out: "Lockhart found Peters a curious figure, half bandit and half gentleman. He brought books for Lockhart and made a great show of his generosity. Yet he had a ruthless streak that chilled the blood. He had lived for some years in England as an anarchist exile and had even been tried at the Old Bailey for the murder of three policemen. To the surprise of many, he had been acquitted. In conversations with Lockhart he recalled the happy years he had spent living in London as a gangster. After five days of imprisonment in the Loubianka, Lockhart was transferred to the Kremlin. Accusations continued to be levelled against him in the press and he was told that he was to be put on trial for his life. Yet the trial was continually delayed and he eventually heard that it was unlikely to go ahead." On 2nd October, 1918, the British government arranged for Lockhart to be exchanged for captive Soviet officials such as Maxim Litvinov. By 1921 the Kronstadt sailors had become disillusioned with the Bolshevik government. They were angry about the lack of democracy and the policy of War Communism. The Soviet historian, David Shub, has argued: "On 1 March 1921, the sailors of Kronstadt revolted against Lenin. Mass meetings of 15,000 men from various ships and garrisons passed resolutions demanding immediate new elections to the Soviet by secret ballot; freedom of speech and the press for all left-wing Socialist parties; freedom of assembly for trade unions and peasant organizations; abolition of Communist political agencies in the Army and Navy; immediate withdrawal of all grain requisitioning squads, and re-establishment of a free market for the peasants." On 28th February, 1921, the crew of the battleship, Petropavlovsk, passed a resolution calling for a return of full political freedoms. On 4th March they issued the following statement: "Comrade workers, red soldiers and sailors. We stand for the power of the Soviets and not that of the parties. We are for free representation of all who toil. Comrades, you are being misled. At Kronstadt all power is in the hands of the revolutionary sailors, of red soldiers and of workers. It is not in the hands of White Guards, allegedly headed by a General Kozlovsky, as Moscow Radio tells you." Eugene Lyons, the author of Workers’ Paradise Lost: Fifty Years of Soviet Communism: A Balance Sheet (1967), pointed out: "The hundreds of large and small uprisings throughout the country are too numerous to list, let alone describe here. The most dramatic of them, in Kronstadt, epitomizes most of them. What gave it a dimension of supreme drama was the fact that the sailors of Kronstadt, an island naval fortress near Petrograd, on the Gulf of Finland, had been one of the main supports of the putsch. Now Kronstadt became the symbol of the bankruptcy of the Revolution. The sailors on the battleships and in the naval garrisons were in the final analysis peasants and workers in uniform." Lenin denounced the Kronstadt Uprising as a plot instigated by the White Army and their European supporters. On 6th March, Leon Trotsky issued a statement: "I order all those who have raised a hand against the Socialist Fatherland, immediately to lay down their weapons. Those who resist will be disarmed and put at the disposal of the Soviet Command. The arrested commissars and other representatives of the Government must be freed immediately. Only those who surrender unconditionally will be able to count on the clemency of the Soviet Republic." Trotsky then ordered the Red Army to attack the Kronstadt sailors. Felix Dzerzhinsky was also involved in putting down the uprising. Victor Serge pointed out: "Lacking any qualified officers, the Kronstadt sailors did not know how to employ their artillery; there was, it is true, a former officer named Kozlovsky among them, but he did little and exercised no authority. Some of the rebels managed to reach Finland. Others put up a furious resistance, fort to fort and street to street.... Hundreds of prisoners were taken away to Petrograd and handed to the Cheka; months later they were still being shot in small batches, a senseless and criminal agony. Those defeated sailors belonged body and soul to the Revolution; they had voiced the suffering and the will of the Russian people. This protracted massacre was either supervised or permitted by Dzerzhinsky." Some observers claimed that many of the victims would die shouting, "Long live the Communist International!" and "Long live the Constituent Assembly!" It was not until the 17th March that government forces were able to take control of Kronstadt. An estimated 8,000 people (sailors and civilians) left Kronstadt and went to live in Finland. Official figures suggest that 527 people were killed and 4,127 were wounded. Historians who have studied the uprising believe that the total number of casualties was much higher than this.It is claimed that over 500 sailors at Kronstadt were executed for their part in the rebellion. Leon Trotsky also accused Dzerzhinsky of being responsible for the massacre: "The truth of the matter is that I personally did not participate in the least in the suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion, nor in the repressions following the suppression. In my eyes this very fact is of no political significance. I was a member of the government, I considered the quelling of the rebellion necessary and therefore bear responsibility for the suppression. Concerning the repressions, as far as I remember, Dzerzhinsky had personal charge of them and Dzerhinsky could not tolerate anyone's interference with his functions (and properly so). Whether there were any needless victims I do not know. On this score I trust Dzerzhinsky more than his belated critics." Dzerzhinsky was aware that the British continued to conspire against the Bolshevik government. The two main figures in this was Boris Savinkov, a former Russian terrorist and member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party and Sidney Reilly, an agent of MI6. Dzerzhinsky decided to establish his own anti-Bolshevik organization, Monarchist Union of Central Russia (also known as "The Trust"). As Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972) pointed out: "Boris Savinkov... was given to understand that all the plotters inside Russia were waiting for was an assurance of massive support from the anti-Bolsheviks outside Russia. Soon Savinkov's own agents were being smuggled in and out of Russia." Savinkov asked Reilly to carry out investigations into "The Trust". Reilly contacted Ernest Boyce, the head of the Russian section of MI6. Boyce confirmed that the organization was apparently a movement of considerable power within Russia. Its agents had supplied valuable intelligence to the Secret Services of a number of anti-Bolshevik countries and was convinced that it was not under the control of Russian Secret Service. Unknown to Reilly, Boyce was in the pay of Cheka. Sidney Reilly knew Winston Churchill was a passionate supporter of intervention. He told him that Boris Savinkov was the best man to coordinate an overthrow of the Bolsheviks. Reilly arranged for Churchill to meet Savinkov. Churchill agreed that that Savinkov was a man of greater stature than any of the other Russian expatriates and that he was the only man who might organize a successful counter-revolution. Prime Minister David Lloyd George had doubts about trying to overthrow the Bolsheviks: "Savinkov is no doubt a man of the future but I need Russia at the present moment, even if it must be the Bolsheviks. Savinkov can do nothing at the moment, but I am sure he will be called on in time to come. There are not many Russians like him." The Foreign Office was unimpressed with Savinkov describing him as "most unreliable and crooked". Churchill replied that he thought that he "was a great man and a great Russian patriot, in spite of the terrible methods with which he has been associated". Churchill rejected the advice of his advisors on the grounds that "it is very difficult to judge the politics in any other country". With the agreement with Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6, it was decided to send Savinkov back into Russia. Richard Deacon has argued that "It was not that he (Savinkov) did not realise there was a risk of deception, but that he had become desperate in his quest for a solution to the problem of defeating the Bolsheviks. His impatience caused him not merely to take a cautious gamble but to risk his life in the cause of counter-revolution." On 10th August 1924, Savinkov left for Russia. Nineteen days later Izvestia announced that Savinkov had been arrested. Over the next few months the newspaper announced that he had been condemned to death; sentence had been commuted to ten years' imprisonment and finally released. It was reported that he was living in a comfortable house in Loubianka Square. Savinkov wrote to Sidney Reilly, that he had changed his views of the Bolsheviks: "How many illusions and fairy tales have I buried here in the Loubianka! I have met men in the GPU whom I have known and trusted from my youth up and who are nearer to me than the chatter-boxes of the foreign delegation of the Social-Revolutionaries... I cannot deny that Russia is reborn." Reilly believed the letter had been written by the GPU. A long letter appeared in The Morning Post on 8th September, 1924: "I claim the great privilege of being one of his most intimate friends and devoted followers, and on me devolves the sacred duty of vindicating his honour. Contrary to the affirmation of your correspondent, I was one of the very few who knew of his intention to penetrate into Soviet Russia. On receipt of a cable from him, I hurried back, at the beginning of July, from New York, where I was assisting my friend, Sir Paul Dukes, to translate and to prepare for publication Savinkov's latest book, The Black Horse. Every page of it is illuminated by Savinkov's transcendent love for his country and by his undying hatred of the Bolshevist tyrants. Since my arrival here on July 19th, I have spent every day with Savinkov up to August 10th, the day of his departure for the Russian frontier. I have been in his fullest confidence, and all his plans have been elaborated conjointly with me. His last hours in Paris were spent with me." Boris Savinkov died on 7th May, 1925. According to the government he committed suicide by jumping from a window in the Lubyanka Prison. However, other sources claim that he was killed in prison by agents of the All-Union State Political Administration (GPU). Sidney Reilly insisted that Savinkov was murdered in August 1924: "Savinkov was killed when attempting to cross the Russian frontier and a mock trial, with one of their own agents as chief actor, was staged by the Cheka in Moscow behind closed doors." Ernest Boyce, the MI6 station chief in Helsinki, wrote to Sidney Reilly asking him to meet the leaders of Monarchist Union of Central Russia in Moscow. Reilly replied: "Much as I am concerned about my own personal affairs which, as you know, are in a hellish state. I am, at any moment, if I see the right people and prospects of real action, prepared to chuck everything else and devote myself entirely to the Syndicate's interests. I was fifty-one yesterday and I want to do something worthwhile, while I can." According to Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service (2010), Boyce had sent Reilly into Russia without clearing the scheme with his superiors in London. "Boyce had to take some of the blame for the tragedy. Back in London, as recalled by Harry Carr, his assistant in Helsinki" he was "carpeted by the Chief for the role he had played in this unfortunate affair." Reilly crossed the Finnish border on 25th September 1925. At a house outside Moscow two days later he had a meeting with the leaders of MUCR, where he was arrested by the secret police. Reilly was told he would be executed because of his attempts to overthrow the Bolshevik government in 1918. According to the Soviet account of his interrogation, on 13th October 1925, Reilly wrote to Felix Dzerzhinsky, saying he was ready to cooperate and give full information on the British and American Intelligence Services. Sidney Reilly's appeal failed and he was executed on 5th November 1925. Dzerzhinsky transformed Cheka into the Government Political Administration (OGPU). One OGPU official admitted that in the first ten years of its existence: "We have executed some twenty or thirty thousand persons, perhaps fifty thousand. They were all spies, traitors, enemies within our ranks, a very small number in proportion to the persons of this kind then in Russia. We instituted the red terror at a time of war, when the enemy was marching upon us from without and the enemy within was preparing to help him. Scotland Yard executed spies and traitors also in war time." Felix Dzerzhinsky died of a heart attack on 20th July 1926.Cheka

Red Terror

Kronstadt Uprising

Monarchist Union of Central Russia

Government Political Administration

Primary Sources

(1) The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution was published by the Soviet government in 1924. The encyclopaedia included a collection of autobiographies and biographies of over two hundred people involved in the Russian Revolution. Felix Dzerzhinsky was one of those invited to write his autobiography.

The February Revolution freed me from the central Moscow prison. Until August 1917, I looked in Moscow, and then in that month I was one of the Moscow delegates to the RSDRP. In the October Revolution, I was a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee, and then I was entrusted with the task of organizing the Extraordinary Commission for the Struggle against Sabotage and Counterrevolution I was appointed its Chairman, holding at the same time the post of Commissar for Internal Affairs.

(2) Richard Deacon, A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972)

Dzerzhinsky had started his career as a student when he joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party, but he soon grew impatient with their aims and switched to the Social Democratic Labour Party and then, when the split between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks came in 1903, he joined the Bolsheviks and soon attracted the attention of Lenin. He was ruthless, cold, clear-headed, gifted with organisational talents and insisted from the start that he must have full powers and not be subject to any supervision. Such was the regard Lenin had for the man that he was given these powers without reservation.

Dzerzhinsky had studied the techniques of both espionage and counter-espionage and he knew that the first task of his Secret Service must be to protect the country from the forces of counter-revolution.

Of course the plans for this new Secret Service had been discussed in some detail a few months before while the Kerensky Provisional Government was still in being. Lenin knew that the forces of moderation were too weak to retain power. On 25 October the Bolsheviks staged their own revolution and not a single regiment in the St. Petersburg garrison made a stand against the revolutionaries. Kerensky fled and the Bolsheviks took over. The moderates who had supported the abdication of the Czar were treated just as brutally by the Bolsheviks as were the Czarists before them.

Dzerzhinsky ordered the arrest of many Ochrana officers and agents, but some of them, under threats of death or life imprisonment, were forcibly persuaded to work for the Soviet regime. Even Vassilyev himself a few years later was approached while in exile in Munich and asked by an agent of Dzerzhinsky if he would enter the service of the Bolshevik Government as a spy. "The sum of money offered as a bribe was quite considerable," he stated, "but I have seldom in my life experienced such satisfaction as I felt at the moment when I had the privilege of throwing that gentleman downstairs."

For the first few days of its existence the new Secret Service of Russia was largely a one-man operation. Dzerzhinsky first imposed a communications blanket between the Soviet Government and the rest of Russia. Post, telephones, telegraphs, even messengers were banned to all non-Bolsheviks. This was of vital security importance for the first few days after the second revolution for it meant that many members of the Kerensky administration did not know what was happening, did not, in fact, realise they were no longer in the Government. Dzerzhinsky maintained this secrecy for weeks, sealing off all possibilities of communication between what he termed "the enemy" and the Soviet Government. Nobody knew what was happening until it happened, usually until an arrest was made.

(3) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

Since the first massacres of Red prisoners by the Whites, the murders of Volodarsky and Uritsky and the attempt against Lenin (in the summer of 1918), the custom of arresting and, often, executing hostages had become generalized and legal. Already Cheka, which made mass arrests of suspects, the was tending to settle their fate independently, under formal control of the Party, but in reality without anybody's knowledge.

The Party endeavoured to head it with incorruptible men like the former convict Dzerzhinsky, a sincere idealist, ruthless but chivalrous, with the emaciated profile of an Inquisitor: tall forehead, bony nose, untidy goatee, and an expression of weariness and austerity. But the Party had few men of this stamp and many Chekas.

I believe that the formation of the Chekas was one of the gravest and most impermissible errors that the Bolshevik leaders committed in 1918 when plots, blockades, and interventions made them lose their heads. All evidence indicates that revolutionary tribunals, functioning in the light of day and admitting the right of defence, would have attained the same efficiency with far less abuse and depravity. Was it necessary to revert to the procedures of the Inquisition?

By the beginning of 1919, the Chekas had little or no resistance against this psychological perversion and corruption. I know for a fact that Dzerzhinsky judged them to be "half-rotten", and saw no solution to the evil except in shooting the worst Chekists and abolishing the death-penalty as quickly as possible.

(4) Bolshevik newspaper, Krasnaya Gazeta, announcing the start of the Red Terror on 1st September, 1918.

We will turn our hearts into steel, which we will temper in the fire of suffering and the blood of fighters for freedom. We will make our hearts cruel, hard, and immovable, so that no mercy will enter them, and so that they will not quiver at the sight of a sea of enemy blood. We will let loose the floodgates of that sea. Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies in scores of hundreds. Let them be thousands; let them drown themselves in their own blood. For the blood of Lenin and Uritsky, Zinovief and Volodarski, let there be floods of the blood of the bourgeois - more blood, as much as possible.

(5) David Shub, Lenin (1948)

In his little room Dzerzhinsky was constantly sharpening the weapon of the Soviet dictatorship. To Dzerzhinsky was brought the mass of undigested rumours from all parts of Petrograd. With the aid of picked squads of Chekists, Dzerzhinsky undertook to purge the city. At night his men moved from the dark streets into apartment houses; towards dawn they returned with i their haul. Few if any challenged the authority of these men. Their password was enough: Cheka, the all-powerful political police.

Little time was wasted sifting evidence and classifying people rounded up in these night raids. Woe to him who did not disarm all suspicion at once. The prisoners were generally hustled to the old police station not far from the Winter Palace. Here, with or without perfunctory interrogation, they were stood up against the courtyard wall and shot. The staccato sounds of death were muffled by the roar of truck motors kept going for the purpose.

Dzerzhinsky furnished the instrument for tearing a new society out of the womb of the old - the instrument of organized, systematic mass terror. For Dzerzhinsky the class struggle meant exterminating "the enemies of the working class". The "enemies of the working class" were all who opposed the Bolshevik dictatorship.

Furthermore, Dzerzhinsky was conscious that terror was perhaps the only means of making "proletarian dictatorship" prevail in peasant Russia. In a conversation with Abramovich, in August 1917, he expressed impatience with the conventional socialist view that the correlation of real political and social forces in a country could only change through the process of economic and political development, the evolution of new forms of economy, rise of new social classes, and so on. "Couldn't this correlation be altered?" Dzerzhinsky asked. "Say, through the subjection or extermination of some classes of society?"

Dzerzhinsky was the man who directed the actual operations of the Cheka, but Lenin assumed full responsibility for the terror. On 8 January 1918, the Council of People's Commissars set up battalions of bourgeois men and women to dig trenches. The Red Guards stationed as their 'surveillance' received the order to shoot anyone who resisted. A month later the All-Russian Cheka declared that "counter-revolutionary agitators" and also "all those trying to escape to the Don region in order to join the counter-revolutionary troops... will he shot on the spot by the Cheka squads".

The same punishment was ordered for those found distributing or posting anti-government leaflets. Not only political crimes were dealt with in this fashion. In Briansk the death penalty by shooting was ordered for drunkenness, and in Viatka the same was ordered for violators of the eight-o'clock curfew. In Rybinsk "shooting without warning" followed any congregation of people on the streets, and in the Kaluga province those failing to meet military levies in time were likewise ordered to be shot. The same "crime" was punished in Zmyev by drowning the victim in the Dniester River "with a stone around his neck".

(6) Felix Dzerzhinsky, interviewed in Novaia Zhizn (14th July, 1918)

We stand for organized terror - this should be frankly admitted. Terror is an absolute necessity during times of revolution. Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government and of the new order of life. We judge quickly. In most cases only a day passes between the apprehension of the criminal and his sentence. When confronted with evidence criminals in almost every case confess; and what argument can have greater weight than a criminal's own confession.

(7) Victor Serge, along with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, had attempted to mediate between the Kronstadt sailors and the Soviet government. His account of the uprising appeared in his book Memoirs of a Revolutionary.

The final assault was unleashed by Tukhacevsky on 17 March, and culminated in a daring victory over the impediment of the ice. Lacking any qualified officers, the Kronstadt sailors did not know how to employ their artillery; there was, it is true, a former officer named Kozlovsky among them, but he did little and exercised no authority. Some of the rebels managed to reach Finland. Others put up a furious resistance, fort to fort and street to street; they stood and were shot crying, "Long live the world revolution! Hundreds of prisoners were taken away to Petrograd and handed to the Cheka; months later they were still being shot in small batches, a senseless and criminal agony. Those defeated sailors belonged body and soul to the Revolution; they had voiced the suffering and the will of the Russian people. This protracted massacre was either supervised or permitted by Dzerzhinsky.

(8) Karl Radek, Felix Dzerzhinski (1935)

The Social-Democratic Party of Poland grew out of the great strikes that swept the industrial areas of Poland during the nineties... One might say that this party was the predecessor of the Communist Party of Poland as a mass party, and was the child of Felix Dzerzhinski’s indefatigable efforts and endless labour. ‘Joseph’ – it was by this name that he was known among the masses of Polish workers – came to be the most beloved of all the Polish leaders.

Tall, well built, with ardent eyes, quick, passionate speech, thus I first met him in the autumn of 1903, when he came to Gracow for a time to hide from tsarist detectives and at the same time to improve the apparatus for circulating Polish Social-Democratic literature, the publication of which had been resumed largely due to his initiative. He won the love and esteem not only of the older workers, but also of the youth then coming into the movement. In their eyes he was surrounded by a halo by reason of his terms in prison and exile and his reputation as Party organizer. His opinion was valued not only by Rosa but even by veteran Tyszka who had great organizational experience and who combined sound Marxian scholarship with wonderful political sensitivity. On all practical questions of the movement Joseph’s opinion was almost decisive. How did he obtain this authority? In fact, what was the personal origin of this energetic revolutionist, so strict towards himself and towards everybody else too, this man able to inspire and lead them all?

He was born in Lithuania, in the Ossmiansk district, in the family of a small Polish landowner. It was in that district that Joseph Pilsudski was born, several years earlier. Lithuania was at that time cowed by memories of ‘ hangman’ Muraviov – of the punishments meted out by tsarism for the year 1863. The homes of the gentry were alive with thought of those whom the tsarist satrap had executed, or had exiled into penal servitude for participation in the uprising. The youth of the intelligentsia cherished thoughts of the struggle against tsarism for independence of the country. The leaders of the Polish Socialist Party, organized in the last decade of the nineteenth -century, for the most part came from the younger generation of these Polish landowner families. One of the few who rejected the road of nationalism and went over without hesitation to the camp of the international labour movement, was Dzerzhinski. His action is probably to be explained by the fact that being of a comparatively poor family he had seen the Lithuanian peasant masses at closer quarters and was also familiar with the life of the craftsmen of the small towns, and found he was nearer them than to the nobility and its ideals.

There was no factory proletariat in Lithuania. There were Polish and Jewish craftsmen, and it was among them that sixteen-year-old Dzerzhinski began his work. The necessity of working among Polish and Jewish apprentices in a country where the majority of the peasantry was Lithuanian may explain the international trend of Dzerzhinski’s feeling and thought. Lie studied socialism through Polish and Russian works, and for the sake of his work among the Jewish workers he studied Yiddish. Later it was a great joke to us that at the head-quarters of Polish Social-Democracy, which contained quite a number of Jews, only Dzerzhinski, former gentleman of Poland, and Catholic, could read Yiddish. The frequent imprisonments of Dzerzhinski gave him time to study most of the available literature on socialism and he joined the Polish movement with a thoroughly worked-out conception of life. The literature of Polish Social-Democracy, including its organ Sprazca Robotnicza (‘Labour Affairs’), published in Paris in 1894-1895, reached him only later when on the basis of his own experience and thinking, he had already, in the main, come to the same conclusions as our theorists had. The basis for his views had been given by Russian Marxist literature. You might say that he was an expression of the identity of the Polish and Russian labour movements.

His value to the movement was not only in the firmness of his views, but also in the unshakable revolutionary decisiveness he brought into the movement. The Polish nobility of the borders, which had grown up in struggles with the Tartars, and later with the Lithuanian and Ukrainian peasantry, had been distinguished from time immemorial by great energy. It was the most resolute type of Polish society. Dzerzhinski had absorbed ideas foreign to this medium, but defended them with the same energy with which the Polish border landed class had defended their class interests. Dzerzhinski did not recognize difficulties or defeats any more than the Skszetuskis, the Wolodyjewskis and other heroes of the Polish frontier landowners famed in Polish historical novels had done. Dangers existed only to be overcome, defeats only to discover one’s errors and learn by them, and reforge one’s sword for further battles. Most of the landed class who came over to the side of the revolutionary classes were of the ‘penitent nobleman’ type. But Dzerzhinski’s mastery of revolutionary thought enabled him fully to identify himself with the working class, and to feel himself an inseparable part of it. He was not a man who idealized the working class from a distance. In the course of his long illegal activities he had lived with workers, eaten with them from a common platter, shared their beds, known them intimately with all the failings resulting from their history, but also with all that is great in them, pregnant with socialism. In all moments of danger he was confident he could find workers who would not give him away, that with them and by their assistance he would be able once again to build up the shattered organization, that they would muster a military detachment prepared afresh to go into struggle, fearing neither hunger nor cold, nor afraid to leave wife and children, nor afraid of long years of solitude in the Akatui prison or the faraway swamps of Siberia. In the course of this life among the Working class the raw iron of his proletarian idea was tempered to supple steel, and this is the quality that Felix Dzerzhinski brought into the Polish Social-Democratic movement. In the illegal work preceding 1905 this young revolutionist became a leader. When the October Manifesto released him from his imprisonment in the tenth division of the Warsaw-fortress where he had been incarcerated in July, 1905, following a mass Party conference called by him in the Dobia Woods near Warsaw, nobody had the slightest doubt that he, Dzerzhinski, was the leader of Social-Democracy. During the few months of mass movement up to his arrest in July he was a flame inspiring the whole party. Who can forget the days when Marcin Kasprzak was being tried by court martial? Kasprzak was a worker, one of the founders of the Party, on trial for armed resistance to arrest, in the spring of 1904, in a secret printing-works. The city was filled with troops, there were mass arrests. On a new press Dzerzhinski and Ganecki ran off proclamations calling for a general strike. Dzerzhinski personally went through the lines of gendarmes meant to isolate the working-class districts, and carried copies of the proclamations round his waist. Tall, strapping, head high, he passed through the ranks of soldiers and gendarmes who were searching every passer-by. He looked bravely into the eyes of a gendarme, who could not make up his mind to stop him. He remained in the memory of the Warsaw workers for long years, as a legend of a resolute revolutionist. When he was caught in Dobia Woods he made the comrades give him all the papers which it was impossible to destroy in order to take all the responsibility upon himself. In Dobia all those arrested were kept under the convoy of the Cossacks, but Dzerzhinski immediately started propaganda among them. Had there not been a change of guard he would have succeeded in organizing an escape.

(9) Eugene Lyons, Workers’ Paradise Lost: Fifty Years of Soviet Communism: A Balance Sheet (1967)

Now that Soviet communism has vaulted over a quarter-century of Stalin dominance to rest its claim to legitimate succession on Lenin alone, there is a tendency to romanticize his character. It is argued, even by some opponents of communism, that he was humane, idealistic, and so on. Yet there is little that Stalin did, except in its scale, that was not done first by Lenin. Stalin simply carried to insane extremes the crimes first sanctified by Lenin.

It was Lenin, it should not be forgotten, who devised the first terror machine, the Cheka, and put a sanctimonious sadist, Felix Dzerzhinsky, at its head. It was Lenin who ordered the murder of thousands of innocent "hostages"; dispersed the first and only democratically elected legislative body after the Bolshevik seizure of power, the Constituent Assembly; crushed the Kronstadt revolt of his own Red sailors; raised lies and falsification to prime virtues in his system.