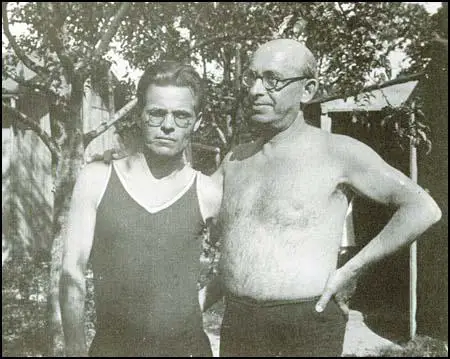

Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman, the son of a Jewish businessman, was born in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, on 21st November, 1870. At the time the territory was part of the Russian Empire. His father, a wholesaler in the shoe industry, was prosperous enough to be allowed to move to St. Petersburg.

Berkman grew up in comfortable surroundings, that including servants and a summer house. He attended a gymnasium reserved for the privileged elements of society.

On 1st March, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. The bomb blast shattered the windows of his classroom. That evening, his older brother, who sympathized with the revolutionists, told him that he had been killed by the People's Will. As the author of Anarchist Portraits (1995), has pointed out, Berkman "was deeply moved by the martyrdom of the populists, five of whom were hanged for their part in the assassination. He was inspired by their idealism and courage, and from that time forward their example lingered in his thoughts."

His mother's brother, Mark Natanson, was a close friend of Peter Kropotkin, and was also involved in revolutionary activity. Berkman was later to write that Natanson was "my ideal of a noble and great man". At the age of fifteen he was already reading revolutionary literature and was expelled from school for "precocious godlessness, dangerous tendencies, and insubordination."

Berkman also became aware of the racism in Russia for when his father died, the family was deprived of the right to live in the capital and were forced to live in Kovno, a town in the Jewish Pale of Settlement. In 1887 his mother died and the following year he decided to move to the United States.

On his arrival in New York City Berkman joined the principal Jewish anarchist group, Pioneers of Liberty. Soon afterwards he began living with Emma Goldman, a Russian immigrant who was working in a clothing factory in Rochester. Berkman and Goldman both became involved in the campaign to free the men convicted of the Haymarket Bombing. They were also influenced by the anarchist writings of Johann Most.

In 1892 Berkman and Goldman started a small business in Worcester, Massachusetts, providing lunches for local workers. Later that year Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers Union called out its members at the Steel Homestead plant owned by Henry Frick and Andrew Carnegie. Frick took the controversial decision to employ 300 strikebreakers from the Pinkerton Detective Agency. The men were brought in on armed barges down the Monongahela River. The strikers were waiting for them and a day long battle took place. Ten men were killed and 60 wounded before the governor obtained order by placing Homestead under martial law.

Berkman was appalled by Frick's behaviour and decided to make a dramatic gesture against capitalism. After gaining entry into his office, Berkman shot Henry Frick three times and stabbed him twice. However, Frick survived the attack and made a full-recovery. Found guilty of attempted murder, Berkman was sent to Western Penitentiary of Pennsylvania in Allegheny City.

After ten years in prison, Berkman wrote to Emma Goldman: "My youthful ideal of a free humanity in tile vague future, has become clarified and crystallized into the living truth of Anarchy, as the sustaining elemental force of my everyday existence." Berkman was released in 1906. He wrote that "I feel like one recovering from a long illness: very weak, but with a touch of joy in life."

After the death of Johann Most, Berkman and Emma Goldman became the leaders of the anarchist movement in the United States. They published the radical journal, Mother Earth and books such as Goldman's Anarchism and Other Essays (1910) and Berkman's Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist (1912). They also helped organize the Ferrer School in New York City and industrial disputes such as the Lawrence Textile Strike.

On the outbreak of the First World War both Berkman and Emma Goldman became involved in the campaign to keep the United States out of the conflict. They also organized anti-militarist rallies in New York City and went on several lecture tours in an attempt to "arouse public opinion against the growing war hysteria".

Berkman moved to San Francisco and in January, 1916, started a new anarchist journal, Blast. When five months later a bomb went off killing six people in the city. The authorities suspected that the bomb had been planted by anti-war campaigners and Berkman was arrested but later released. Thomas Mooney, a local trade union leader was falsely convicted of the offence but spent the next twenty-three years in prison before being released.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, it was claimed that Berkman had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. Berkman was arrested, tried and sentenced to two years in Atlanta Federal Prison, seven months of which he spent in solitary confinement for protesting against officers beating fellow prisoners.

In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed A. Mitchell Palmer as his attorney general. Soon after taking office, a government list of 62 people believed to hold "dangerous, destructive and anarchistic sentiments" was leaked to the press. It was also revealed that these people had been under government surveillance for many years. Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

A. Mitchell Palmer claimed that Communist agents from Russia were planning to overthrow the American government. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Berkman, Emma Goldman, Mollie Steimer, and 245 other people, were deported to Russia.

Henry L. Mencken wrote that "Berkman was a transparently honest man yet we hunt him as if he were a mad dog - and finally kick him out of the country. And with him goes a shrewder head and a braver spirit than has been seen in public among us since the American Civil War."

In January 1920 Berkman and Goldman toured Russia collecting material for the Museum of the Revolution in Petrograd. However, Lenin was a strong opponent of anarchism. He told Nestor Makhno, the most important anarchist in Russia: "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them."

A pact with the anarchists for joint military action against General Anton Denikin and his White Army was signed in March 1919. However, the Bolsheviks did not trust the anarchists and two months later two Cheka agents sent to assassinate Nestor Makhno were caught and executed. Leon Trotsky, commander-in-chief of the Bolsheviks forces, ordered the arrest of Makhno and sent in troops to Hulyai-Pole dissolve the agricultural communes set up by the Makhnovists. With Makhno's power undermined, a few days later, Denikin forces arrived and completed the job, liquidating the local soviets as well. In September, 1919, the Red Army was able to force Denikin's army to retreat to the shores of the Black Sea.

Leon Trotsky now turned to dealing with the anarchists and outlawed the Makhnovists. According to the author of Anarchist Portraits (1995): "There ensued eight months of bitter struggle, with losses heavy on both sides. A severe typhus epidemic augmented the toll of victims. Badly outnumbered, Makhno's partisans avoided pitched battles and relied on the guerrilla tactics they had perfected in more than two years of civil war."

Berkman, who had already been appalled by the way that Lenin and Trotsky had dealt with the Kronstadt Uprising decided to leave Russia. "Grey are the passing days. One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. The slogans of the Revolution are forsworn, its ideals stifled in the blood of the people. The breath of yesterday is dooming millions to death; the shadow of today hangs like a black pall over the country. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under foot. The Revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness.... I have decided to leave Russia."

After a brief stay in Stockholm, he lived in Berlin, where he published several pamphlets and books on the Bolshevik government, including The Bolshevik Myth (1925). In this book he wrote: "One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October, 1917. The slogans of the Revolution are forsworn, its ideals stifled in the blood of the people. The breath of yesterday is dooming millions to death: the shadow of today hangs like a black pall over the country. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under foot. The Revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness."

Berkman also edited the book on political persecution under the Bolsheviks, Letters from Russian Prisons (1925). Later that year he moved to Paris and joined several anarchists living in exile. This included Peter Arshinov, Vsevolod Volin, Emma Goldman, Nestor Makhno, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker.

In 1926 Nestor Makhno joined forces broke with Peter Arshinov to publish their controversial Organizational Platform, which called for a General Union of Anarchists. This was opposed by Berkman, Vsevolod Volin, Emma Goldman, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker, who argued that the idea of a central committee clashed with the basic anarchist principle of local organisation.

Berkman socialised with a group of radicals that lived in Paris. This included Emily Coleman, Douglas Garman, Edgell Rickword, Peggy Guggenheim, Laurence Vail, William Gerhardie and John Holms. Guggenheim later commented: "During that winter (of 1928) I met Emma Goldman and Alexander (Sasha) Berkman. They were glamorous revolutionary figures and one expected them to be quite different. They were frightfully human."

Victor Serge was one of those who greatly admired Goldman and Berkman: "The American background of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman estranged them from the Russians, and turned them into representatives of an idealistic generation that had completely vanished in Russia. They embodied the humanistic rebellion of the turn of the century: Emma Goldman with her organizing flair and practical disposition, her narrow but generous prejudices, and her self-importance, typical of American women devoted to social work."

Berkman concentrated on his writing and in 1929 published Now and After: The ABC of Communist Anarchism. The author of Anarchist Portraits (1995) wrote: "Berkman was not an original theorist. His ideas were drawn largely from Kropotkin and other founding fathers of the movement. But he was a lucid and gifted writer with a firm and fluent command of his subject... The result was a classic, ranking with Kropotkin's Conquest of Bread as the clearest exposition of communist anarchism in English or any other language."

Berkman suffered from poor health and underwent two unsuccessful operations for a prostate condition. In constant pain and having to rely on the financial help of friends, Alexander Berkman committed suicide on 28th June, 1936. This was just three weeks before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, which, as Emma Goldman suggests, might have given him some hope for the future.

Primary Sources

(1) In March 1916 Alexander Berkman commented in Blast on the decision by the American government to suppress the radical journal Revolt.

We are not going to say that it is an outrage. Why should the government not commit outrages? Invasion of personal liberty, suppression of free speech and free press, silencing non-conformists and protestants, shooting down rebellious workers - all this is of the very essence of government.

We don't complain. We understand Wilson's position. He must do hit master's bidding. This is the "sane policy." But we want to warn the weather cock in the White House that it may not prove safe. Suppressior of the voice of discontent leads to assassination. Vide Russia.

(2) Alexander Berkman, diary entries while living in Russia (March, 1921)

7th March, 1921: Distant rumbling reaches my ears as I cross the Nevsky. It sounds again, stronger and nearer, as if rolling toward me. All at once I realize the artillery is being fired. It is 6 p.m. Kronstadt has been attacked! My heart is numb with despair; something has died within me.

17th March, 1921: Kronstadt has fallen today. Thousands of sailors and workers lie dead in its streets. Summary execution of prisoners and hostages continues.

30th September, 1921: One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under the foot. The revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness. The Bolshevik myth must be destroyed. I have decided to leave Russia.

(3) Alexander Berkman, The Bolshevik Myth (1925)

One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October, 1917. The slogans of the Revolution are forsworn, its ideals stifled in the blood of the people. The breath of yesterday is dooming millions to death: the shadow of today hangs like a black pall over the country. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under foot. The Revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness.

(4) Alexander Berkman, The Bolshevik Myth (1925)

Grey are the passing days. One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. The slogans of the Revolution are forsworn, its ideals stifled in the blood of the people. The breath of yesterday is dooming millions to death; the shadow of today hangs like a black pall over the country. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under foot. The Revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness.... I have decided to leave Russia.

(5) Paul Avrich, Anarchist Portraits (1990)

With the death of Johann Most in 1906 (shortly before Berkman's release from prison), Berkman, together with Emma Goldman, became the leading figure in the American anarchist movement. Addressing meetings, organizing demonstrations, editing periodicals, and agitating among the workers and unemployed, he did more than any of his associates, apart from Goldman herself, to futher the libertarian cause. Under his editorship, Goldman's Mother Earth became the foremost anarchist journal in the United States and one of the best produced anywhere in the world. In view of his crushing imprisonment, Emma later recalled, he "surprised everybody by the vigour of his style and the clarity of his thoughts." In addition to his chores on her journal, he edited and corrected the proofs of Goldman's Anarchism and Other Essays (published by the Mother Earth press in 1910), as he was to do with all her future books, including her memorable autobiography, Living My Life.

Berkman, at the same time, was active in other areas of work. In 1910 and 1911 he helped organize the Ferrer School in New York, which encouraged a libertarian spirit among its students, and he served as one of its first teachers. During the next few years, moreover, he presided over demonstrations for the unemployed and agitated for such causes as the Lawrence textile strike of 1912 and the Ludlow, massacre of 1914. With the outbreak of the First World War, he organized anti-militarist rallies in New York and made extended lecture tours through the country, trying to arouse public opinion against the growing war hysteria.

(6) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

The American background of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman estranged them from the Russians, and turned them into representatives of an idealistic generation that had completely vanished in Russia. They embodied the humanistic rebellion of the turn of the century.

Berkman with the inward tension that sprang from his idealism in years long past. His eighteen years in an American prison had frozen him in the attitudes of his youth when, as an act of solidarity with a strike, he had offered up his life by shooting at one of the steel barons. When his tension relaxed he became dejected, and I could not help thinking that he was often troubled by ideas of suicide. In fact, it was only much later that he was to end his life.