Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg, the youngest of five children of a lower middle-class Jewish family was born in Zamość, in the Polish area of Russia, on 5th March, 1871. A disease in early life kept her in bed for a whole year. It was wrongly treated as tuberculosis of the bone and caused irreparable damage. (1)

Rosa was a very intelligent child and could read and write by the age of five. At school she was always top of the class. Tsar Alexander III followed a repressive policy against those seeking political reform. Alexander also pursued a policy of Russification of national minorities. This included imposing the Russian language and Russian schools on the German, Polish and Finnish peoples living in the Russian Empire. (2)

At her High School in Warsaw, there was a rigid quota for Jews and the use of the native Polish language, even among the students themselves, was strictly forbidden. She became a supporter of Polish independence and developed socialist views. At sixteen, when she graduated at the top of her class from her school, she was denied the gold medal because of "an oppositional attitude toward the authorities." (3) It is claimed that she saw women raped and men murdered for being Jewish. (4)

At that time there was an estimated 5,500,000 Jews living in Russia. Under a law introduced by Tsar Alexander III, all Russian Jews were forced to live in what became known as the Pale of Jewish Settlement. Exceptions were made for rich business people, students and for certain professions. The Pale comprised the ten Polish and fifteen neighbouring Russian provinces, stretching from Riga to Odessa, from Silesia to Vilna and Kiev. This led to a large increase in Jews leaving Russia. Of these, more than 90 per cent settled in the United States. (5)

Women were not allowed to study at university in Russia and in 1889 Rosa Luxemburg emigrated to Zurich where she studied philosophy, law and political economy. It was during this period that she first began to study the works of Adam Smith and Karl Marx. Rosa was also active in the local working-class movement and came into contact with Pavel Axelrod, George Plekhanov, Vera Zasulich and Alexandra Kollontai. She also became a close friend of Julian Marchlewski, a fellow student who was a committed socialist revolutionary. (6)

Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "Physically, the girl Rosa did not seem made to be a tragic heroine or a leader of men. A childhood hip ailment had left her body twisted, frail, and slight. She walked with an ungainly limp. But when she spoke, what people saw were large, expressive eyes glowing with compassion, sparkling with laughter, burning with combativeness, flashing with irony and scorn. When she took the floor at congresses or meetings, her slight frame seemed to grow taller and more commanding. Her voice was warm and vibrant (a good singing voice, too), her wit deadly, her arguments wide ranging and addressed, as a rule, more to the intelligence than to the feelings of her auditors." (7)

Emile Vandervelde, a socialist from Belgium, was one of those who was very impressed by her public speaking. "Her opponents had a great deal of trouble in holding their ground against her. I can see her now: how she sprang to her feet out of the sea of delegates and jumped onto a chair to make herself better heard. Small, delicate and dainty in the summer dress which cleverly concealed her physical defects, she advocated her cause with such magnetism in her eyes and with such fiery words that she enthralled and won over the great majority of the congress, who raised their hands in favour of the acceptance of her mandate." (8)

Rosa Luxemburg and Marxism

In 1890 Rosa Luxemburg met Leo Jogiches, who had already served a term of imprisonment for revolutionary activity. One of his friends said: "He was a very clever and able debater. In his presence one felt that this was no commonplace man. He devoted his whole existence to his work as a socialist, and his followers idolised him." He had inherited money from his grandfather and was willing to use this for the good of the socialist cause. "She had never met anyone like him. Knowledgeable, dedicated, driven, meticulous, mysterious, a gold mine of information." (9)

Rosa and Leo began "a lifelong personal intimacy (without benefit of religious or civil ceremony)". Her friend, Clara Zetkin, claims they had a very successful relationship: "He was one of those very masculine personalities - an extremely rare phenomenon these days - who can tolerate a great female personality in loyal and happy comradeship, without feeling her growth and development to be fetters on his own ego." (10)

Rosa Luxemburg settled in Berlin where she joined the Social Democratic Party. A committed revolutionary, Luxemburg campaigned with Karl Kautsky against the revisionist Eduard Bernstein, who argued that the best way to obtain socialism in an industrialized country was through trade union activity and parliamentary politics. In 1900 she published an attack on Bernstein in her pamphlet, Reform or Revolution, that was published in 1900. (11)

In the pamphlet, Luxemburg made it clear that she was a committed Marxist: "Today he who wants to pass as a socialist, and at the same time declare war on Marxian doctrine, the most stupendous product of the human mind in the century, must begin with involuntary esteem for Marx. He must begin by acknowledging himself to be his disciple, by seeking in Marx’s own teachings the points of support for an attack on the latter, while he represents this attack as a further development of Marxian doctrine. On this account, we must, unconcerned by its outer forms, pick out the sheathed kernel of Bernstein’s theory. This is a matter of urgent necessity for the broad layers of the industrial proletariat in our Party." (12)

In 1903 Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches and Julian Marchlewski, to form the Social Democratic Party of Poland. As it was an illegal organization, she went to Paris to edit the party's newspaper, Sprawa Robotnicza (Workers' Cause). The arrival of Felix Dzerzhinsky helped the movement to grow and together they formed the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania. While in Paris she became friends with Jean Jaurès and Édouard-Marie Vaillant, Marxist leaders of the French working-class movement. (13)

Bolsheviks and Mensheviks

At the Second Congress of the German Social Democratic Party held in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Julius Martov. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Leon Trotsky commented that "the split came unexpectedly for all the members of the congress. Lenin, the most active figure in the struggle, did not foresee it, nor had he ever desired it. Both sides were greatly upset by the course of events." Martov won the vote 28-23 but Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. (14)

Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks. Trotsky supported Martov. So also did George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Lev Deich, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Irakli Tsereteli, Moisei Uritsky, Vera Zasulich, Noi Zhordania and Fedor Dan. Trotsky argued that "Lenin's behaviour seemed unpardonable to me, both horrible and outrageous. And yet, politically it was right and necessary, from the point of view of organization. The break with the older ones, who remained in the preparatory stages, was inevitable in any case. Lenin understood this before anyone else did. He made an attempt to keep Plekhanov by separating him from Zasulich and Axelrod. But this, too, was quite futile, as subsequent events soon proved." (15)

Luxemburg disagreed with the theories of Lenin. In 1904 she published Organizational Questions of the Russian Democracy, where she argued: "Lenin’s thesis is that the party Central Committee should have the privilege of naming all the local committees of the party. It should have the right to appoint the effective organs of all local bodies from Geneva to Liege, from Tomsk to Irkutsk. It should also have the right to impose on all of them its own ready-made rules of party conduct... The Central Committee would be the only thinking element in the party. All other groupings would be its executive limbs." Luxemburg disagreed with Lenin's views on centralism and suggested that any successful revolution that used this strategy would develop into a communist dictatorship. (16)

1905 Russian Revolution

During the 1905 Revolution Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches returned to Warsaw where they were soon arrested. Luxemburg's experiences during the failed revolution changed her views on international politics. Until then, Luxemburg believed that a socialist revolution was most likely to take place in an advanced industrialized country such as Germany or France. She now argued it could happen in an underdeveloped country like Russia. "All the oppositional and revolutionary forces in Russian society can now make themselves felt: the elementary, confused outrage of the peasant, the liberal dissatisfaction of the progressive nobility, the thrust towards freedom of the educated intelligentsia, of the professors, man of letters and lawyers. Based on the revolutionary mass movement of the urban proletariat, and marching along behind it, they can all lead a great army of fighting people, one people, against Tsarism." (17)

At the Social Democratic Party Congress in September 1905, Luxemburg called for party members to be inspired by the attempted revolution in Russia. "Previous revolutions, especially the one in 1848, have shown that in revolutionary situations it is not the masses who have to be held in check, but the parliamentarians and lawyers, so that they do not betray the masses and the revolution." She then went onto quote from The Communist Manifesto: "The workers have nothing to lose but their chains; they had a world to win." (18)

August Bebel, the leader of the SDP, did not share Luxemburg's views that now was the right time for revolution. He later recalled: "Listening to all that, I could not help glancing a couple of times at the toes of my boots to see if they weren't already wading in blood." However, he preferred Luxemburg to Eduard Bernstein and he appointed her to the editorial board of the SPD newspaper, Vorwarts (Forward). In a letter to Leo Jogiches she wrote: "The editorial board will consist of mediocre writers, but at least they'll be kosher... Now the Leftists have got to show that they are capable of governing." (19)

August Bebel

Rosa Luxemburg had been deeply influenced by the achievements of Father Georgi Gapon and the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg. In 1906 she published The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions. She argued that a general strike had the power to radicalize the workers and bring about a socialist revolution. "The mass strike is the first natural, impulsive form of every great revolutionary struggle of the proletariat and the more highly developed the antagonism is between capital and labour, the more effective and decisive must mass strikes become. The chief form of previous bourgeois revolutions, the fight at the barricades, the open conflict with the armed power of the state, is in the revolution today only the culminating point, only a moment on the process of the proletarian mass struggle." (20)

These views were not well received by August Bebel and other party leaders. In a letter to Clara Zetkin she wrote: "The situation is simply this: August Bebel, and still more so the others, have completely spent themselves on behalf of parliamentarism and in parliamentary struggles. Whenever anything happens which transcends the limits of parliamentarism, they are completely hopeless - no, even worse than that, they try their best to force everything back into the parliamentary mould, and they will furiously attack as an enemy of the people anyone who wants to go beyond these limits." (21)

In 1907 Luxemburg began teaching at the Social Democratic Party school in Berlin. According to Bertram D. Wolfe: "Unlike other German pundits, who did little more than repeat Marx's formulae in new works, she developed first an original, mildly heretical interpretation of the labour theory of value (Introduction to National Economy) then ventured to cross swords with Marx himself in a critical appraisal and revision of the arid and weak Second Volume of Das Kapital." (22)

Karl Liebknecht

Luxemburg began working closely with Karl Liebknecht, a leading figure in the anti-militarist section of the SDP. In 1907 he published Militarism and Anti-Militarism. In the book he argued: "Militarism is not specific to capitalism. It is moreover normal and necessary in every class-divided social order, of which the capitalist system is the last. Capitalism, of course, like every other class-divided social order, develops its own special variety of militarism; for militarism is by its very essence a means to an end, or to several ends, which differ according to the kind of social order in question and which can be attained according to this difference in different ways. This comes out not only in military organization, but also in the other features of militarism which manifest themselves when it carries out its tasks. The capitalist stage of development is best met with an army based on universal military service, an army which, though it is based on the people, is not a people’s army but an army hostile to the people, or at least one which is being built up in that direction."

Liebknecht then went on to argue why the socialist movement should concentrate on persuading young people to adopt the philosophy of anti-militarism: "Here is a great field full of the best hopes of the working-class, almost incalculable in its potential, whose cultivation must not at any cost wait upon the conversion of the backward sections of the adult proletariat. It is of course easier to influence the children of politically educated parents, but this does not mean that it is not possible, indeed a duty, to set to work also on the more difficult section of the proletarian youth. The need for agitation among young people is therefore beyond doubt. And since this agitation must operate with fundamentally different methods – in accordance with its object, that is, with the different conditions of life, the different level of understanding, the different interests and the different character of young people – it follows that it must be of a special character, that it must take a special place alongside the general work of agitation, and that it would be sensible to put it, at least to a certain degree, in the hands of special organizations." (23)

Luxemburg worked very closely with Liebknecht. A fellow member of the SDP, Paul Frölich has argued: "He (Liebknecht) never seemed to get tired... besides speaking at meetings, doing office work, and acting as defence counsel in court, he could still spend whole nights debating and drinking merrily with the comrades. And even if the street dust did cover his soul at times, it could not stifle the genuine enthusiasm which imbued all his activities. It was this devotion to the cause, the passionate temperament and this capacity for enthusiasm that Rosa valued. She recognised the true revolutionary in him, even if they sometimes disagreed on details of party tactics. They worked together and complemented each other very well, especially in the struggle against militarism and the danger of war." (24)

Rosa Luxemburg described Liebknecht to her friend, Hans Diefenbach. "Liebknecht... spent nearly all his time in parliament, meetings, commissions, conferences; running and rushing, always ready to jump from the commuter-train into the tram, and from the tram into a car; every pocket stuffed full of memo pads, his arms full of the latest newspapers which, of course, he never finds time to read; body and soul covered with street dust, and yet always with a kind and youthful smile on his face." (25)

At this time Germany became involved in an arms race with Britain. The Royal Navy built its first dreadnought in 1906. It was the most heavily-armed ship in history. She had ten 12-inch guns (305 mm), whereas the previous record was four 12-inch guns. The gun turrets were situated higher than user and so facilitated more accurate long-distance fire. In addition to her 12-inch guns, the ship also had twenty-four 3-inch guns (76 mm) and five torpedo tubes below water. In the waterline section of her hull, the ship was armoured by plates 28 cm thick. It was the first major warship driven solely by steam turbines. It was also faster than any other warship and could reach speeds of 21 knots. A total of 526 feet long (160.1 metres) it had a crew of over 800 men. It cost over £2 million, twice as much as the cost of a conventional battleship.

Germany built its first dreadnought in 1907 and plans were made for building more. The British government believed it was necessary to have twice the number of these warships than any other navy. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the German Ambassador, Count Paul Metternich, and told him that Britain was willing to spend £100 million to frustrate Germany's plans to achieve naval supremacy. That night he made a speech where he spoke out on the arms race: "My principle is, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, less money for the production of suffering, more money for the reduction of suffering." (26)

Kaiser Wilhelm II gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph in October 1908 where he outlined his policy of increasing the size of his navy: "Germany is a young and growing empire. She has a world-wide commerce which is rapidly expanding and to which the legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds. Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect that commerce and her manifold interests in even the most distant seas. She expects those interests to go on growing, and she must be able to champion them manfully in any quarter of the globe. Her horizons stretch far away. She must be prepared for any eventualities in the Far East. Who can foresee what may take place in the Pacific in the days to come, days not so distant as some believe, but days at any rate, for which all European powers with Far Eastern interests ought steadily to prepare?" (27)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, had consistently described Germany as Britain's "secret and insidious enemy". He used his newspapers to urge an increase in defence spending and in October 1909 he commissioned Robert Blatchford, to visit Germany and then write a series of articles setting out the dangers. The German's, Blatchford wrote, were making "gigantic preparations" to destroy the British Empire and "to force German dictatorship upon the whole of Europe". He complained that Britain was not prepared for was and argued that the country was facing the possibility of an "Armageddon". (28)

Karl Liebknecht led the campaign against the building of more dreadnoughts. Other members of the Social Democratic Party who supported Liebknecht became known as the Left Radicals. This included Leo Jogiches, Franz Mehring, Clara Zetkin, Paul Frölich, Hugo Eberlein, Heinrich Blücher, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker, Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Anton Pannekoek. The leadership of the SDP agreed with the build-up of the armed forces in Germany and they saw a significant growth in their popularity. For example, in 1907 they won 43 seats in the Reichstag. Four years later they increased this to 110 seats. (29)

Luxemburg's book on economic imperialism, The Accumulation of Capital, was published in 1913. This was an impressive achievement and Franz Mehring described her as the "most brilliant head that has yet appeared among the scientific heirs of Marx and Engels." This work established herself on the extreme left-wing of the party. She continued to advocate the need for a violent overthrow of capitalism and she gradually became alienated from previous party colleagues, Karl Kautsky and August Bebel. However, according to her biographer, John Peter Nettl, Luxemburg refused the form a radical group within the SDP. "By temperament as much as necessity, Rosa Luxemburg acted as an individual and on her own behalf." (30)

The First World War

On 4th August, 1914, Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy." (31)

Paul Frölich, a supporter of Liebknecht in the Social Democratic Party (SDP), argued: "On the day of the vote only one man was left: Karl Liebknecht. Perhaps that was a good thing. That only one man, one single person, let it be known on a rostrum being watched by the whole world that he was opposed to the general war madness and the omnipotence of the state - this was a luminous demonstration of what really mattered at the moment: the engagement of one's whole personality in the struggle. Liebknecht's name became a symbol, a battle-cry heard above the trenches, its echoes growing louder and louder above the world-wide clash of arms and arousing many thousands of fighters against the world slaughter." (32)

John Peter Nettl claims that two left-wing members of the SDP, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin, were horrified by these events. They had great hopes that the SDP, the largest socialist party in the world with over a million members, would oppose the war: "Both Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin suffered nervous prostration and were at one moment near to suicide. Together they tried on 2 and 3 August to plan an agitation against the war; they contacted 20 SPD members with known radical views, but they got the support of only Liebknecht and Mehring... Rosa sent 300 telegrams to local officials who were thought to be oppositional, asking their attitude to the vote in the Reichstag and inviting them to Berlin for an urgent conference. The results were pitiful." (33)

The Spartacus League

Rosa Luxemburg joined forces with Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Hugo Eberlein to campaign against the war but decided against forming a new party and agreed to continue working within the SPD. Clara Zetkin was initially reluctant to join the group. She argued: "We must ensure the broadest relationship with the masses. In the given situation the protest appears more as a personal beau geste than a political action... It is justified and nice to say that everything is lost, except one's honour. If I wanted to follow my feelings, then I would have telegraphed a yes with great pleasure. But now we must more than ever think and act coolly." (34)

However, by September, 1914, Zetkin was playing a significant role in the anti-war movement. She co-signed with Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Mehring, letters that appeared in socialist newspapers in neutral countries condemning the war. Above all Zetkin used her position as editor-in-chief of the Die Gleichheit (Equality) and as Secretary of the Women's Secretariat of the Socialist International to propagate the positions of the anti-war movement. (35)

Clara Zetkin who later recalled: "The struggle was supposed to begin with a protest against the voting of war credits by the social-democratic Reichstag deputies, but it had to be conducted in such a way that it would be throttled by the cunning tricks of the military authorities and the censorship. Moreover, and above all, the significance of such a protest would doubtless be enhanced, if it was supported from the outset by a goodly number of well-known social-democratic militants." (36)

Karl Liebknecht continued to make speeches in public about the war: "The war is not being waged for the benefit of the German or any other peoples. It is an imperialist war, a war over the capitalist domination of the world market... The slogan 'against Tsarism' is being used - just as the French and British slogan 'against militarism' - to mobilise the noble sentiments, the revolutionary traditions and the hopes of the people for the national hatred of other peoples." (37)

In May 1915, Liebknecht published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued that: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity." (38)

In December, 1915, 19 other deputies joined Karl Liebknecht in voting against war credits. The following year a series of demonstrations took place. Some of these were "spontaneous outbursts by unorganised groups of people, usually women: anger would flare when a shop ran out of food, or put its prices up, or when rations were suddenly cut." These demonstrations often led to bitter clashes between workers and the police. (39)

Rosa Luxemburg continued to protest against Germany's involvement in the war and on the 19th February, 1915, she was arrested. In a letter to her friend, Mathilde Jacob, she described her first day in prison: "Incidentally, so that you don't get any exaggerated ideas about my heroism, I'll confess, repentantly, that when I had to strip to my chemise and submit to a frisking for the second time that day, I could barely hold back the tears. Of course, deep inside, I was furious with myself at such weakness, and I still am. Also on the first evening, what really dismayed me was not the prison cell any my sudden exclusion from the land of the living, but the fact that I had to go to bed without a night-dress and without having combed my hair." (40)

As a political prisoner she was allowed books and writing materials. With the help of Mathilde Jacob she was able to smuggle out articles and pamphlets she had written to Franz Mehring. In April 1915, Mehring published some of this material in a new journal, Die Internationale. Other contributors included Clara Zetkin, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker and Heinrich Ströbel. The journal included articles by Mehring on the attitude of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to the problem of war and Zetkin dealt with the position of women in wartime. The main objective of the journal was to criticise the official policy of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) towards the First World War. (41)

In the first edition Luxemburg contributed an article on the way the SDP reacted to the outbreak of the war. "Faced with this alternative, which it had been the first to recognize and bring to the masses’ consciousness, Social Democracy backed down without a struggle and conceded victory to imperialism. Never before in the history of class struggles, since there have been political parties, has there been a party that, in this way, after fifty years of uninterrupted growth, after achieving a first-rate position of power, after assembling millions around it, has so completely and ignominiously abdicated as a political force within twenty-four hours, as Social Democracy has done. Precisely because it was the best-organized and best-disciplined vanguard of the International, the present-day collapse of socialism can be demonstrated by Social Democracy’s example." (42)

Luxemburg also wrote a pamphlet entitled The Crisis of German Social Democracy during this period. She exposed the lies that were told to those men who willingly volunteered to fight in a war that would only last a few weeks: "Mass slaughter has become the tiresome and monotonous business of the day and the end is no closer... Gone is the euphoria. Gone the patriotic noise in the streets... The trains full of reservists are no longer accompanied by virgins fainting from pure jubilation. They no longer greet the people from the windows of the train with joyous smiles.... The cannon fodder loaded onto trains in August and September is moldering in the killing fields of Belgium, the Vosges, and Masurian Lakes where the profits are springing up like weeds. It’s a question of getting the harvest into the barn quickly. Across the ocean stretch thousands of greedy hands to snatch it up. Business thrives in the ruins. Cities become piles of ruins; villages become cemeteries; countries, deserts; populations are beggared; churches, horse stalls. International law, treaties and alliances, the most sacred words and the highest authority have been torn in shreds." (43)

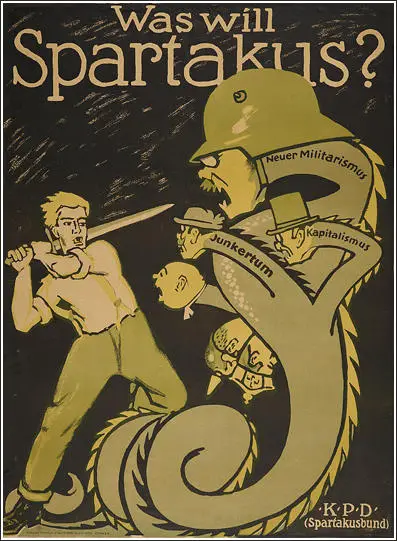

Over the next few months members of this group were arrested for their anti-war activities and spent several short spells in prison. This included Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, Hugo Eberlein, Leo Jogiches, Heinrich Blücher, Paul Levi, Franz Mehring, Julian Marchlewski and Hermann Duncker. On the release of Luxemburg in February 1916, it was decided to establish an underground political organization called Spartakusbund (Spartacus League). The Spartacus League publicized its views in its illegal newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Like the Bolsheviks in Russia, they argued that socialists should turn this nationalist conflict into a revolutionary war. (44)

The group published an attack on all European socialist parties (except the Independent Labour Party): "By their vote for war credits and by their proclamation of national unity, the official leaderships of the socialist parties in Germany, France and England (with the exception of the Independent Labour Party) have reinforced imperialism, induced the masses of the people to suffer patiently the misery and horrors of the war, contributed to the unleashing, without restraint, of imperialist frenzy, to the prolongation of the massacre and the increase in the number of its victims, and assumed their share in the responsibility for the war itself and for its consequences." (45)

Eugen Levine was one of the first people to join the Spartacus League. He had been disturbed by the "new wave of national prejudice and chauvinism". His wife, Rosa Levine-Meyer, was shocked when he stated that the war would last "at least eighteen months or two years". This upset his mother who had been convinced by government propaganda that "the war would end by Christmas". Levine told Rosa that the "war would be accompanied by a severe world crisis and revolutionary shocks". He added that during a war "it is easier to convert thousands of workers than one single well-meaning intellectual". (46)

On 1st May, 1916, Rosa Luxemburg, organised a anti-war demonstration on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. It was a great success and by eight o'clock in the morning around 10,000 people assembled in the square. The police charged at Karl Liebknecht who was about to speak to the large crowd. "For two hours after Liebknecht's arrest masses of people swirled around Potsdamer Platz and the neighbouring streets, and there were many scuffles with the police. For the first time since the beginning of the war open resistance to it had appeared on the streets of the capital." (47)

As a member of the Reichstag, Liebknecht had parliamentary immunity from prosecution. When the military judicial authorities demanded that this immunity was removed, the Reichstag agreed and he was placed on trial. On 28th June 1916, Liebknecht was sentenced to two years and six months hard labour. The day Liebknecht was sentenced, 55,000 munitions workers went on strike. The government responded by arresting trade union leaders and having them conscripted into the German Army.

Luxemburg responded by publishing a handbill defending Liebknecht and accusing members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) who had removed his parliamentary immunity as being "political dogs". She claimed that: "A dog is someone who licks the boots of the master who has dealt him kicks for decades. A dog is someone who gaily wags his tail in the muzzle of martial law and looks straight into the eyes of the lords of the military dictatorship while softly whining for mercy... A dog is someone who, at his government's command, abjures, slobbers, and tramples down into the muck the whole history of his party and everything it has held sacred for a generation." (48)

Rosa Luxemburg was re-arrested on 10th July, 1916. So also was the seventy-year-old Franz Mehring, Ernest Meyer and Julian Marchlewski. Leo Jogiches now became the leader of the Spartacus League and the editor of its newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Luxemburg, wrote regularly for each edition, sometimes writing three-quarters of a whole issue. She also worked on her book, Introduction to Economics. (49)

The Russian Revolution

As Nicholas II was supreme commander of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline in his support in Russia during the First World War. In January 1917, General Aleksandr Krymov returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma. Krymov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. "A revolution is imminent and we at the front feel it to be so. If you decide on such an extreme step (the overthrow of the Tsar), we will support you. Clearly there is no other way." (50)

The Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich shared the views of Rodzianko and sent a letter to the Tsar: "The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs." (51)

On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Arthur Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges." (52)

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working in Petrograd, with strong left-wing opinions, wrote to his aunt, Anna Maria Philips, claiming that the country was on the verge of revolution: "Most exciting times. I knew this was coming sooner or later but did not think it would come so quickly... Whole country is wild with joy, waving red flags and singing Marseillaise. It has surpassed my wildest dreams and I can hardly believe it is true. After two-and-half years of mental suffering and darkness I at last begin to see light. Long live Great Russia who has shown the world the road to freedom. May Germany and England follow in her steps." (53)

On 10th March, 1917, the Tsar had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that Nicholas II should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed." (54)

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government and a few days later announced that all political prisoners would be allowed to return to their homes. Rosa Luxemburg was delighted to hear about the overthrow of Nicholas II. She wrote to her close friend, Hans Diefenbach: "You can well imagine how deeply the news from Russia has stirred me. So many of my old friends who have been languishing in prison for years in Moscow, St Petersburg, Orel and Riga are now walking about free. How much easier that makes my own imprisonment here!" (55)

In her prison cell she wrote several articles on the overthrow of Nicholas II. "The revolution in Russia has been victorious over bureaucratic absolutism in the first phase. However, this victory is not the end of the struggle, but only a weak beginning." She also condemned the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries who had joined the government. "The coalition ministry is a half-measure which burdens socialism with all the responsibility, without even beginning to allow it the full possibility of developing its programme. It is a compromise which, like all compromises is finally doomed to fiasco." (56)

Luxemburg's fears were realised when Alexander Kerensky became the new prime minister and soon after taking office, he announced the July Offensive. In a long article in Spartakusbriefe she condemned Kerensky's strategy. "Although the Russian Republic professes to be fighting a purely defensive war, in reality it is participating in an imperialist one, and, while it appeals to the right of nations to self-determination, in practice it is aiding and abetting the rule of imperialism over foreign nations." (57)

On 24th October, 1917, Lenin wrote a letter to the members of the Central Committee: "The situation is utterly critical. It is clearer than clear that now, already, putting off the insurrection is equivalent to its death. With all my strength I wish to convince my comrades that now everything is hanging by a hair, that on the agenda now are questions that are decided not by conferences, not by congresses (not even congresses of soviets), but exclusively by populations, by the mass, by the struggle of armed masses… No matter what may happen, this very evening, this very night, the government must be arrested, the junior officers guarding them must be disarmed, and so on… History will not forgive revolutionaries for delay, when they can win today (and probably will win today), but risk losing a great deal tomorrow, risk losing everything." (58)

Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev opposed this strategy. They argued that the Bolsheviks did not have the support of the majority of people in Russia or of the international proletariat and should wait for the elections of the proposed Constituent Assembly "where we will be such a strong opposition party that in a country of universal suffrage our opponents will be compelled to make concessions to us at every step, or we will form, together with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, non-party peasants, etc., a ruling bloc which will fundamentally have to carry out our programme." (59)

Leon Trotsky supported Lenin's view and urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The Smolny Institute became the headquarters of the revolution and was transformed into a fortress. Trotsky reported that the "chief of the machine-gun company came to tell me that his men were all on the side of the Bolsheviks". (60)

The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. The Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace. (61)

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Victor Nogin (Trade and Industry), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice), Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War), Nikolai Krylenko (War Affairs), Pavlo Dybenko (Navy Affairs), Ivan Skvortsov-Stepanov (Finance), Vladimir Milyutin (Agriculture), Ivan Teodorovich (Food), Georgy Oppokov (Justice) and Nikolai Glebov-Avilov (Posts & Telegraphs). (62)

After Nicholas II abdicated, the new Provisional Government announced it would introduce a Constituent Assembly. Elections were due to take place in November. Some leading Bolsheviks believed that the election should be postponed as the Socialist Revolutionaries might well become the largest force in the assembly. When it seemed that the election was to be cancelled, five members of the Bolshevik Central Committee, Victor Nogin, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Vladimir Milyutin submitted their resignations.

Kamenev believed it was better to allow the election to go ahead and although the Bolsheviks would be beaten it would give them to chance to expose the deficiencies of the Socialist Revolutionaries. "We (the Bolsheviks) shall be such a strong opposition party that in a country of universal suffrage our opponents will be compelled to make concessions to us at every step, or we will form, together with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, non-party peasants, etc., a ruling bloc which will fundamentally have to carry out our programme." (63)

Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17).

The Constituent Assembly opened on 18th January, 1918. "The Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries occupied the extreme left of the house; next to them sat the crowded Socialist Revolutionary majority, then the Mensheviks. The benches on the right were empty. A number of Cadet deputies had already been arrested; the rest stayed away. The entire Assembly was Socialist - but the Bolsheviks were only a minority." (64)

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. The following day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. "In all Parliaments there are two elements: exploiters and exploited; the former always manage to maintain class privileges by manoeuvres and compromise. Therefore the Constituent Assembly represents a stage of class coalition.

In the next stage of political consciousness the exploited class realises that only a class institution and not general national institutions can break the power of the exploiters. The Soviet, therefore, represents a higher form of political development than the Constituent Assembly." (65)

Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia. Maxim Gorky, a world famous Russian writer and active revolutionary, pointed out: "For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished and tens of thousands of workers and peasants... The unarmed revolutionary democracy of Petersburg - workers, officials - were peacefully demonstrating in favour of the Constituent Assembly. Pravda lies when it writes that the demonstration was organized by the bourgeoisie and by the bankers.... Pravda knows that the workers of the Obukhavo, Patronnyi and other factories were taking part in the demonstrations. And these workers were fired upon. And Pravda may lie as much as it wants, but it cannot hide the shameful facts." (66)

Rosa Luxemburg agreed with Gorky about the closing down of the Constituent Assembly. In her book, Russian Revolution, written in 1918 but not published until 1922, she wrote: "We have always exposed the bitter kernel of social inequality and lack of freedom under the sweet shell of formal equality and freedom - not in order to reject the latter, but to spur the working-class not to be satisfied with the shell, but rather to conquer political power and fill it with a new social content. It is the historic task of the proletariat, once it has attained power, to create socialist democracy in place of bourgeois democracy, not to do away with democracy altogether." (67)

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, went to interview Luxemburg while she was in prison in Germany. He later reported: "She asked me if the Soviets were working entirely satisfactorily. I replied, with some surprise, that of course they were. She looked at me for a moment, and I remember an indication of slight doubt on her face, but she said nothing more. Then we talked about something else and soon after that I left. Though at the moment when she asked me that question I was a little taken aback, I soon forgot about it. I was still so dedicated to the Russian Revolution, which I had been defending against the Western Allies' war of intervention, that I had had no time for anything else." (68)

As Paul Frölich pointed out: "She (Rosa Luxemburg) was unwilling to see criticism suppressed, even hostile criticism. She regarded unrestricted criticism as the only means of preventing the ossification of the state apparatus into a downright bureaucracy. Permanent public control, and freedom of the press and of assembly were therefore necessary." (69) Luxemburg argued: "Freedom for supporters of the government only, for members of one party only - no matter how numerous they might be - is no freedom at all. Freedom is always freedom for those who think differently." (70)

Luxemburg then went on to make some predictions about the future of Russia. "But with the suppression of political life in the Soviets must become more and more crippled. Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of the press and of assembly, without the free struggle of opinion, life in every public institution dies down and becomes a mere semblance of itself in which the bureaucracy remains as the only active element. Public life gradually falls asleep. A few dozen party leaders with inexhaustible energy and boundless idealism direct and rule. Among these, a dozen outstanding minds manage things in reality, and an elite of the working class is summoned to meetings from time to time so that they can applaud the speeches of the leaders, and give unanimous approval to proposed resolutions, thus at bottom a cliquish set-up - a dictatorship, to be sure, but not the dictatorship rule.of the proletariat: rather the dictatorship of a handful of politicians, i.e., a dictatorship in the bourgeois sense, in the sense of a Jacobin rule... every long-lasting regime based on martial law leads without fail to arbitrariness, and all arbitrary power tends to deprave society." (71)

Brest-Litovsk Treaty

Leon Trotsky led the Russian delegation at Brest-Litovsk that was negotiating with representatives from Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread from Russia to Germany and Austria-Hungary before he had to sign the treaty. (72)

Lenin still argued for a peace agreement, whereas his opponents, including Nickolai Bukharin, Andrey Bubnov, Alexandra Kollontai, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek and Moisei Uritsky, were in favour of a "revolutionary war" against Germany. This belief had been encouraged by the German demands for the "annexations and dismemberment of Russia". In the ranks of the opposition was Lenin's close friend, Inessa Armand, who had surprisingly gone public with her demands for continuing the war with Germany. (73)

Rosa Luxemburg was also opposed to these negotiations as she feared a German victory in the war: "She realised that if the working class of the European Great Powers could not summon up sufficient strength to end the war by revolution, then Germany's defeat was the next best solution. A military victory for ravenous German imperialism under the barbarous regime of Prussian Junkerdom would only lead to the most wanton excesses of the mania for conquest, casting all of Europe and other continents as well into chains, and throwing humanity far back in the quest for progress." (74)

After nine weeks of discussions without agreement, the German Army was ordered to resume its advance into Russia. On 3rd March 1918, with German troops moving towards Petrograd, Lenin ordered Trotsky to accept the terms of the Central Powers. The Brest-Litovsk Treaty resulted in the Russians surrendering the Ukraine, Finland, the Baltic provinces, the Caucasus and Poland.

Trotsky later admitted that he was totally against signing the agreement as he thought that by continuing the war with the Central Powers it would help encourage socialist revolutions in Germany and Austria: "Had we really wanted to obtain the most favourable peace, we would have agreed to it as early as last November. But no one raised his voice to do it. We were all in favour of agitation, of revolutionizing the working classes of Germany, Austria-Hungary and all of Europe." (75)

Rosa Luxemburg was furious when she discovered the terms of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. "Having failed to halt the storming chariot of imperialism, the German proletariat is now being dragged behind it to overpower socialism and democracy all over Europe. Over the bones of the Russian, Ukrainian, Baltic and Finnish proletarians; over the national existence of the Belgians, Poles, Lithuanians, Rumanians; over the economic ruin of France, the German worker is tramping, wading over knee-deep in blood, onward, to plant the victorious banner of German imperialism everywhere. (76)

Morgan Philips Price later recalled in My Three Revolutions (1969) that her opposition to the Brest-Litovsk was connected to her dislike of Lenin: "She (Rosa Luxemburg) did not like the Russian Communist Party monopolizing all power in the Soviets and expelling anyone who disagreed with it. She feared that Lenin's policy had brought about, not the dictatorship of the working classes over the middle classes, which she approved of but the dictatorship of the Communist Party over the working classes. The dictatorship of a class - yes, she said, but not the dictatorship of a party over a class." (77)

The German Revolution

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a cease-fire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (78)

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace." (79)

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Kiel soon travelled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power." (80)

Chancellor, Max von Baden, decided to hand over power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy: "You have no right to proclaim the republic." (81)

Karl Liebknecht, who had been released from prison on 23rd October, climbed to a balcony in the Imperial Palace and made a speech: "The day of Liberty has dawned. I proclaim the free socialist republic of all Germans. We extend our hand to them and ask them to complete the world revolution. Those of you who want the world revolution, raise your hands." It is claimed that thousands of hands rose up in support of Liebknecht. (82)

The Social Democratic Party press, fearing the opposition of the left-wing and anti-war Spartacus League, proudly trumpeted their achievements: "The revolution has been brilliantly carried through... the solidarity of proletarian action has smashed all opposition. Total victory all along the line. A victory made possible because of the unity and determination of all who wear the workers' shirt." (83)

Rosa Luxemburg was released from prison in Breslau on 8th November. She went to Cathedral Square, in the centre of the city, where she was cheered by a mass demonstration. Two days later she arrived in Berlin. Her appearance shocked her friends in the Spartacus League: "They now saw what the years in prison had done to her. She had aged, and was a sick woman. Her hair, once deep black, had now gone quite grey. Yet her eyes shone with the old fire and energy." (84)

Eugen Levine went on speaking tours in support of the Spartacus League and was encouraged by the response he received. According to his wife: "His first propaganda tour through the Ruhr and Rhineland was crowned with almost legendary success... They did not come to get acquainted with Communist ideas. At best they were driven by curiosity, or a certain restlessness characteristic of the time of revolutionary upheavels... Levine was regularly received with catcalls and outbursts of abuse but he never failed to calm the storm. He told me jokingly that he often had to play the part of a lion-tamer." (85)

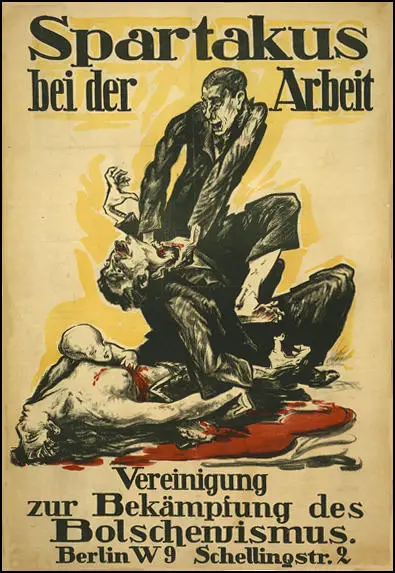

Ebert became concerned about the growing support for the Spartacus League and gave permission for the publishing of a Social Democratic Party leaflet that attacked their activities: "The shameless doings of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg besmirch the revolution and endanger all its achievements. The masses cannot afford to wait a minute longer and quietly look on while these brutes and their hangers-on cripple the activity of the republican authorities, incite the people deeper and deeper into a civil war, and strangle the right of free speech with their dirty hands. With lies, slander, and violence they want to tear down everything that dares to stand in their way. With an insolence exceeding all bounds they act as though they were masters of Berlin." (86)

Heinrich Ströbel, a journalist based in Berlin believed that some leaders of the Spartacus League overestimated their support: "The Spartakist movement, which also influenced a section of the Independents, succeeded in attracting a fraction of the workers and soldiers and keeping them in a state of constant excitement, but it remained without a hold on the great mass of the German proletariat. The daily meetings, processions, and demonstrations which Berlin witnessed... deceived the public and the Spartakist leaders into believing in a following for this revolutionary section which did not exist." (87)

Friedrich Ebert established the Council of the People's Deputies, a provisional government consisting of three delegates from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and three from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Liebknecht was offered a place in the government but he refused, claiming that he would be a prisoner of the non-revolutionary majority. A few days later Ebert announced elections for a Constituent Assembly to take place on 19th January, 1918. Under the new constitution all men and women over the age of 20 had the vote. (88)

As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League." (89)

Luxemburg was aware that the Spartacus League only had 3,000 members and not in a position to start a successful revolution. The Spartacus League consisted chiefly of innumerable small and autonomous groups scattered all over the country. John Peter Nettl has argued that "organisationally Spartacus was slow to develop... In the most important cities it evolved an organised centre only in the course of December... and attempts to arrange caucus meetings of Spartakist sympathisers within the Berlin Workers' and Soldiers' Council did not produce satisfactory results." (90)

Pierre Broué suggests that the large meetings helped to convince Karl Liebknecht that a successful revolution was possible. "Liebknecht, an untiring agitator, spoke everywhere where revolutionary ideas could find an echo... These demonstrations, which the Spartakists had neither the force nor the desire to control, were often the occasion for violent, useless or even harmful incidents caused by the doubtful elements who became involved in them... Liebknecht could have the impression that he was master of the streets because of the crowds which acclaimed him, while without an authentic organisation he was not even the master of his own troops." (91)

A convention of the Spartacus League began on 30th December, 1918. Karl Radek, a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee, argued that the the Soviet government should help the spread of world revolution. Radek was sent to Germany and at the convention he persuaded the delegates to change the name to the German Communist Party (KPD). The convention now discussed whether the KPD should take part in the forthcoming general election.

Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Levi and Leo Jogiches all recognised that a "successful revolution depended on more than temporary support for certain slogans by a disorganised mass of workers and soldiers". (92) As Rosa Levine-Mayer explained the election "had the advantage of bringing the Spartacists closer to the broader masses and acquainting them with Communist ideas. Nor could a set-back, followed by a period of illegality, even if only temporary, be altogether ruled out. A seat in the Parliament would then be the only means of conducting Communist propaganda openly.It could also be foreseen that the workers at large would not understand the idea of a boycott and would not be persuaded to stay aloof; they would only be forced to vote for other parties." (93)

Luxemburg, Levi and Jogiches and other members who wanted to take part in elections were outvoted on this issue. As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "In vain did she (Luxemburg) try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising." (94)

Emil Eichhorn had been appointed head of the Police Department in Berlin. One activist pointed out: "A member of the Independent Socialist Party and a close friend of the late August Bebel, he enjoyed great popularity among revolutionary workers of all shades for his personal integrity and genuine devotion to the working class. His position was regarded as a bulwark against counter-revolutionary conspiracy and was a thorn in the flesh of the reactionary forces." (95)

On 4th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert, ordered the removal of Emil Eichhorn, as head of the Police Department. Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "The Berlin workers greeted the news that Eichhorn had been dismissed with a huge wave of anger. They felt he was being dismissed for siding with them against the attacks of right wing officers and employers. Eichhorn responded by refusing to vacate police headquarters. He insisted that he had been appointed by the Berlin working class and could only be removed by them. He would accept a decision of the Berlin Executive of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, but no other." (96)

The Spartacus League published a leaflet that claimed: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers." It is estimated that over 100,000 workers demonstrated against the sacking of Eichhorn the following Sunday in "order to show that the spirit of November is not yet beaten." (97)

Paul Levi later reported that even with this provocation, the Spartacus League leadership still believed they should resist an open rebellion: "The members of the leadership were unanimous; a government of the proletariat would not last more than a fortnight... It was necessary to avoid all slogans that might lead to the overthrow of the government at this point. Our slogan had to be precise in the following sense: lifting of the dismissal of Eichhorn, disarming of the counter-revolutionary troops, arming of the proletariat." (98)

Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck published a leaflet calling for a revolution. "The Ebert-Scheidemann government has become intolerable. The undersigned revolutionary committee, representing the revolutionary workers and soldiers, proclaims its removal. The undersigned revolutionary committee assumes provisionally the functions of government." Karl Radek later commented that Rosa Luxemburg was furious with Liebknecht and Pieck for getting carried away with the idea of establishing a revolutionary government." (99)

Although massive demonstrations took place, no attempt was made to capture important buildings. On 7th January, Luxemburg wrote in the Die Rote Fahne: "Anyone who witnessed yesterday's mass demonstration in the Siegesalle, who felt the magnificent mood, the energy that the masses exude, must conclude that politically the proletariat has grown enormously through the experiences of recent weeks.... However, are their leaders, the executive organs of their will, well informed? Has their capacity for action kept pace with the growing energy of the masses?" (100)

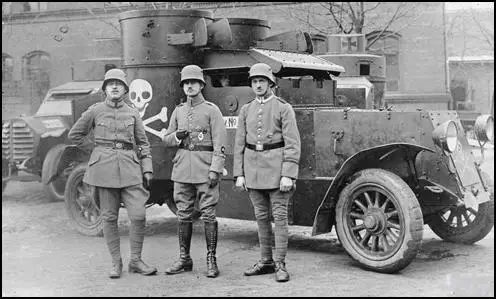

General Kurt von Schleicher, was on the staff of Paul von Hindenburg. In December 1919 he helped organize the Freikorps, in an attempt to prevent a German Revolution. The group was composed of "former officers, demobilized soldiers, military adventurers, fanatical nationalists and unemployed youths". Holding extreme right-wing views, von Schleicher blamed left-wing political groups and Jews for Germany's problems and called for the elimination of "traitors to the Fatherland". (101)

The Freikorps appealed to thousands of officers who identified with the upper class and had nothing to gain from the revolution. There were also a number of privileged and highly trained troops, known as stormtroopers, who had not suffered from the same rigours of discipline, hardship and bad food as the mass of the army: "They were bound together by an array of privileges on the one hand, and a fighting camaraderie on the other. They stood to lose all this if demobilised - and leapt at the chance to gain a living by fighting the reds." (102)

Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, was also in contact with General Wilhelm Groener, who as First Quartermaster General, had played an important role in the retreat and demobilization of the German armies. According to William L. Shirer, the SDP leader and the "second-in-command of the German Army made a pact which, though it would not be publicly known for many years, was to determine the nation's fate. Ebert agreed to put down anarchy and Bolshevism and maintain the Army in all its tradition. Groener thereupon pledged the support of the Army in helping the new government establish itself and carry out its aims." (103)

On the 5th January, Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. Groener later testified that his aim in reaching accommodation with Ebert was to "win a share of power in the new state for the army and the officer corps... to preserve the best and strongest elements of old Prussia". Ebert was motivated by his fear of the Spartacus League and was willing to use "the armed power of the far-right to impose the government's will upon recalcitrant workers, irrespective of the long-term effects of such a policy on the stability of parliamentary democracy". (104)

The soldiers who entered Berlin were armed with machine-guns and armoured cars and demonstrators were killed in their hundreds. Artillery was used to blow the front off the police headquarters before Eichhorn's men abandoned resistance. "Little quarter was given to its defenders, who were shot down where they were found. Only a few managed to escape across the roofs." (105)

rolls of newsprint as barricades (January, 1919)

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal." (106)

Primary Sources

(1) Bertram D. Wolfe, Strange Communists I Have Known (1966)

Physically, the girl Rosa did not seem made to be a tragic heroine or a leader of men. A childhood hip ailment had left her body twisted, frail, and slight. She walked with an ungainly limp. But when she spoke, what people saw were large, expressive eyes glowing with compassion, sparkling with laughter, burning with combativeness, flashing with irony and scorn. When she took the floor at congresses or meetings, her slight frame seemed to grow taller and more commanding. Her voice was warm and vibrant (a good singing voice, too), her wit deadly, her arguments wide ranging and addressed, as a rule, more to the intelligence than to the feelings of her auditors.

She had been a precocious child, gifted with many talents. All her life, to the day of her murder in January, 1919, she was tempted and tormented by longings to diminish her absorption in politics in order to develop to the full the many other capacities of her spirit. Unlike so many political figures, her inner life, as expressed in her letters, her activities, her enthusiasms, reveals a rounded human being. She drew and painted, read great literature in Russian, Polish, German, and French, wrote poetry in the first three of these, continued to be seduced by an interest in anthropology, history, botany, geology, and others of the arts and sciences into which the modern specialized intellect is fragmented. "Interest" is but a cold word for the intensity with which she pursued her studies.

(2) Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or Revolution (1900)

At first view the title of this work may be found surprising. Can the Social-Democracy be against reforms? Can we contrapose the social revolution, the transformation of the existing order, our final goal, to social reforms? Certainly not. The daily struggle for reforms, for the amelioration of the condition of the workers within the framework of the existing social order, and for democratic institutions, offers to the Social-Democracy an indissoluble tie. The struggle for reforms is its means; the social revolution, its aim.

It is in Eduard Bernstein’s theory, presented in his articles on Problems of Socialism, Neue Zeit of 1897-98, and in his book Die Voraussetzungen des Socialismus und die Aufgaben der Sozialdemokratie that we find, for the first time, the opposition of the two factors of the labour movement. His theory tends to counsel us to renounce the social transformation, the final goal of Social-Democracy and, inversely, to make of social reforms, the means of the class struggle, its aim. Bernstein himself has very clearly and characteristically formulated this viewpoint when he wrote: “The Final goal, no matter what it is, is nothing; the movement is everything.”

But since the final goal of socialism constitutes the only decisive factor distinguishing the Social-Democratic movement from bourgeois democracy and from bourgeois radicalism, the only factor transforming the entire labour movement from a vain effort to repair the capitalist order into a class struggle against this order, for the suppression of this order – the question: “Reform or Revolution?” as it is posed by Bernstein, equals for the Social-Democracy the question: “To be or not to be?” In the controversy with Bernstein and his followers, everybody in the Party ought to understand clearly it is not a question of this or that method of struggle, or the use of this or that set of tactics, but of the very existence of the Social-Democratic movement.

Upon a casual consideration of Bernstein’s theory, this may appear like an exaggeration. Does he not continually mention the Social-Democracy and its aims? Does he not repeat again and again, in very explicit language, that he too strives toward the final goal of socialism, but in another way? Does he not stress particularly that he fully approves of the present practice of the Social-Democracy?

That is all true, to be sure. It is also true that every new movement, when it first elaborates its theory and policy, begins by finding support in the preceding movement, though it may be in direct contradiction with the latter. It begins by suiting itself to the forms found at hand and by speaking the language spoken hereto. In time the new grain breaks through the old husk. The new movement finds its forms and its own language.

To expect an opposition against scientific socialism at its very beginning, to express itself clearly, fully and to the last consequence on the subject of its real content: to expect it to deny openly and bluntly the theoretic basis of the Social-Democracy – would amount to underrating the power of scientific socialism. Today he who wants to pass as a socialist, and at the same time declare war on Marxian doctrine, the most stupendous product of the human mind in the century, must begin with involuntary esteem for Marx. He must begin by acknowledging himself to be his disciple, by seeking in Marx’s own teachings the points of support for an attack on the latter, while he represents this attack as a further development of Marxian doctrine. On this account, we must, unconcerned by its outer forms, pick out the sheathed kernel of Bernstein’s theory. This is a matter of urgent necessity for the broad layers of the industrial proletariat in our Party.

No coarser insult, no baser aspersion, can be thrown against the workers than the remarks: “Theocratic controversies are only for academicians.” Some time ago Lassalle said: “Only when science and the workers, these opposite poles of society, become one, will they crush in their arms of steel all obstacles to culture.” The entire strength of the modern labour movement rests on theoretic knowledge.

But doubly important is this knowledge for the workers in the present case, because it is precisely they and their influence in the movement that are in the balance here. It is their skin that is being brought to market. The opportunist theory in the Party, the theory formulated by Bernstein, is nothing else than an unconscious attempt to assure predominance to the petty-bourgeois elements that have entered our Party, to change the policy and aims of our Party in their direction. The question of reform or revolution, of the final goal and the movement, is basically, in another form, but the question of the petty-bourgeois or proletarian character of the labour movement.

It is, therefore, in the interest of the proletarian mass of the Party to become acquainted, actively and in detail, with the present theoretic knowledge remains the privilege of a handful of “academicians” in the Party, the latter will face the danger of going astray. Only when the great mass of workers take the keen and dependable weapons of scientific socialism in their own hands, will all the petty-bourgeois inclinations, all the opportunistic currents, come to naught. The movement will then find itself on sure and firm ground. “Quantity will do it”

(3) Rosa Luxemburg, Organizational Questions of the Russian Democracy (1904)

One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward, written by Lenin, an outstanding member of the Iskra group, is a methodical exposition of the ideas of the ultra-centralist tendency in the Russian movement. The viewpoint presented with incomparable vigor and logic in this book, is that of pitiless centralism. Laid down as principles are: The necessity of selecting, and constituting as a separate corps, all the active revolutionists, as distinguished from the unorganized, though revolutionary, mass surrounding this elite.

Lenin’s thesis is that the party Central Committee should have the privilege of naming all the local committees of the party. It should have the right to appoint the effective organs of all local bodies from Geneva to Liege, from Tomsk to Irkutsk. It should also have the right to impose on all of them its own ready-made rules of party conduct. It should have the right to rule without appeal on such questions as the dissolution and reconstitution of local organizations. This way, the Central Committee could determine, to suit itself, the composition of the highest party organs. The Central Committee would be the only thinking element in the party. All other groupings would be its executive limbs.

Lenin reasons that the combination of the socialist mass movement with such a rigorously centralized type of organization is a specific principle of revolutionary Marxism. To support this thesis, he advances a series of arguments, with which we shall deal below.

Generally speaking it is undeniable that a strong tendency toward centralization is inherent in the Social Democratic movement. This tendency springs from the economic makeup of capitalism which is essentially a centralizing factor. The Social Democratic movement carries on its activity inside the large bourgeois city. Its mission is to represent, within the boundaries of the national state, the class interests of the proletariat, and to oppose those common interests to all local and group interests.

Therefore, the Social Democracy is, as a rule, hostile to any manifestation of localism or federalism. It strives to unite all workers and all worker organizations in a single party, no matter what national, religious, or occupational differences may exist among them. The Social Democracy abandons this principle and gives way to federalism only under exceptional conditions, as in the case of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

It is clear that the Russian Social Democracy should not organize itself as a federative conglomerate of many national groups. It must rather become a single party for he entire empire. However, that is not really the question considered here. What we are considering is the degree of centralization necessary inside the unified, single Russian party in view of the peculiar conditions under which it has to function.

Looking at the matter from the angle of the formal tasks of the Social Democracy, in its capacity as a party of class struggle, it appears at first that the power and energy of the party are directly dependent on the possibility of centralizing the party. However, these formal tasks apply to all active parties. In the case of the Social Democracy, they are less important than is the influence of historic conditions....