Dreadnoughts and the First World War

In October 1905, Admiral Sir John Fisher gained control at the Admiralty as First Sea Lord. Fisher believed the German threat was real and that it was only a matter of time before the fleet across the North Sea would test his own. For the next five years fought to uphold the traditional "two-power standard" by which "the British had attempted to maintain a fleet twice as large as the combined naval forces of its two most likely foes". Alfred Harmsworth, the owner of The Daily Mail, The Times, The Daily Mirror and The Evening News, did what he could to support Fisher in this task. (1)

Britain's first dreadnought was built at Portsmouth Dockyard between October 1905 and December 1906. It was the most heavily-armed ship in history. She had ten 12-inch guns (305 mm), whereas the previous record was four 12-inch guns. The gun turrets were situated higher than user and so facilitated more accurate long-distance fire. In addition to her 12-inch guns, the ship also had twenty-four 3-inch guns (76 mm) and five torpedo tubes below water. In the waterline section of her hull, the ship was armoured by plates 28 cm thick. It was the first major warship driven solely by steam turbines. It was also faster than any other warship and could reach speeds of 21 knots. A total of 526 feet long (160.1 metres) it had a crew of over 800 men. It cost over £2 million, twice as much as the cost of a conventional battleship. (2)

Germany built its first dreadnought in 1907 and plans were made for building more. The British government believed it was necessary to have twice the number of these warships than any other navy. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the German Ambassador, Count Paul Metternich, and told him that Britain was willing to spend £100 million to frustrate Germany's plans to achieve naval supremacy. That night he made a speech where he spoke out on the arms race: "My principle is, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, less money for the production of suffering, more money for the reduction of suffering." (3)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, used his newspapers to urge an increase in defence spending and a reduction in the amount of money being spent on social insurance schemes. In one letter to Lloyd George he suggested that the Liberal government was Pro-German. Lloyd George replied: "The only real pro-German whom I know of on the Liberal side of politics is Rosebery, and I sometimes wonder whether he is even a Liberal at all! Haldane, of course, from education and intellectual bent, is in sympathy with German ideas, but there is really nothing else on which to base a suspicion that we are inclined to a pro-German policy at the expense of the entente with France." (4)

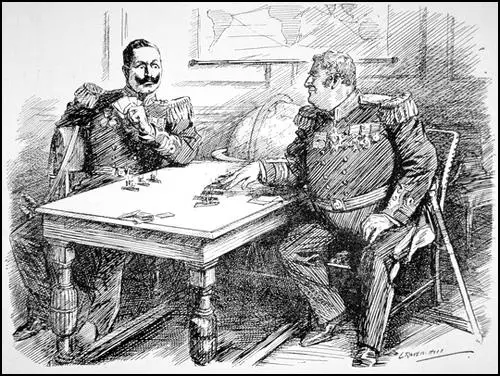

Kaiser Wilhelm II gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph in October 1908 where he outlined his policy of increasing the size of his navy: "Germany is a young and growing empire. She has a world-wide commerce which is rapidly expanding and to which the legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds. Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect that commerce and her manifold interests in even the most distant seas. She expects those interests to go on growing, and she must be able to champion them manfully in any quarter of the globe. Her horizons stretch far away. She must be prepared for any eventualities in the Far East. Who can foresee what may take place in the Pacific in the days to come, days not so distant as some believe, but days at any rate, for which all European powers with Far Eastern interests ought steadily to prepare?" (5)

Grey replied to these comments in the same newspaper: "The German Emperor is ageing me; he is like a battleship with steam up and screws going, but with no rudder, and he will run into something some day and cause a catastrophe. He has the strongest army in the world and the Germans don't like being laughed at and are looking for somebody on whom to vent their temper and use their strength. After a big war a nation doesn't want another for a generation or more. Now it is 38 years since Germany had her last war, and she is very strong and very restless, like a person whose boots are too small for him. I don't think there will be war at present, but it will be difficult to keep the peace of Europe for another five years." (6)

David Lloyd George complained bitterly to H. H. Asquith about the demands being made by Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty, to spend more money on the navy. He reminded Asquith of "the emphatic pledges given by us before and during the general election campaign to reduce the gigantic expediture on armaments built up by our predecessors... but if Tory extravagance on armaments is seen to be exceeded, Liberals... will hardly think it worth their while to make any effort to keep in office a Liberal ministry... the Admiralty's proposals were a poor compromise between two scares - fear of the German navy abroad and fear of the Radical majority at home... You alone can save us from the prospect of squalid and sterile destruction." (7)

Lord Northcliffe had consistently described Germany as Britain's "secret and insidious enemy", and in October 1909 he commissioned Robert Blatchford, to visit Germany and then write a series of articles setting out the dangers. The German's, Blatchford wrote, were making "gigantic preparations" to destroy the British Empire and "to force German dictatorship upon the whole of Europe". He complained that Britain was not prepared for was and argued that the country was facing the possibility of an "Armageddon". (8)

Lloyd George was constantly in conflict with McKenna and suggested that his friend, Winston Churchill, should become First Lord of the Admiralty. Asquith took this advice and Churchill was appointed to the post on 24th October, 1911. McKenna, with the greatest reluctance, replaced him at the Home Office. This move backfired on Lloyd George as the Admiralty cured Churchill's passion for "economy". The "new ruler of the King's navy demanded an expenditure on new battleships which made McKenna's claims seem modest". (9)

The Admiralty reported to the British government that by 1912 Germany would have 17 dreadnoughts, three-fourths the number planned by Britain for that date. At a cabinet meeting David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill both expressed doubts about the veracity of the Admiralty intelligence. Churchill even accused Admiral John Fisher, who had provided this information, of applying pressure on naval attachés in Europe to provide any sort of data he needed. (10)

Admiral Fisher refused to be beaten and contacted King Edward VII about his fears. He in turn discussed the issue with H. H. Asquith. Lloyd George wrote to Churchill explaining how Asquith had now given approval to Fisher's proposals: "I feared all along this would happen. Fisher is a very clever person and when he found his programme in danger he wired Davidson (assistant private secretary to the King) for something more panicky - and of course he got it." (11)

On 7th February, 1912, Churchill made a speech where he pledged naval supremacy over Germany "whatever the cost". Churchill, who had opposed naval estimates of £35 million in 1908, now proposed to increase them to over £45 million. The German Naval Attaché, Captain Wilhelm Widenmann, wrote to Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, in an attempt to explain this change in policy. He claimed that Churchill was "clever enough" to realise that the British public would support "naval supremacy" whoever was in charge "as his boundless ambition takes account of popularity, he will manage his naval policy so as not to damage that" even dropping "the ideas of economy" which he had previously preached. (12)

The Admiralty reported to the British government that by 1912 Germany would have seventeen dreadnoughts, three-fourths the number planned by Britain for that date. At a cabinet meeting David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill both expressed doubts about the veracity of the Admiralty intelligence. Churchill even accused Admiral John Fisher, who had provided this information, of applying pressure on naval attachés in Europe to provide any sort of data he needed. (13)

Admiral Fisher refused to be beaten and contacted King Edward VII about his fears. He in turn discussed the issue with H. H. Asquith. Lloyd George wrote to Churchill explaining how Asquith had now given approval to Fisher's proposals: "I feared all along this would happen. Fisher is a very clever person and when he found his programme in danger he wired Davidson (assistant private secretary to the King) for something more panicky - and of course he got it." (14)

Winston Churchill now advocated spending £51,550,000 on the Navy in 1914. The "new ruler of the King's navy demanded an expenditure on new battleships which made McKenna's claims seem modest". (15) Lloyd George remained opposed to what he saw as inflated naval estimates and was not "prepared to squander money on building gigantic flotillas to encounter mythical armadas". According to George Riddell, a close friend of both men, recorded they were drifting wide apart on principles". (16) Riddell reported there were even rumours that Churchill was "mediating... going over to the other side." (17)

Primary Sources

(1) Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary, speech (December, 1906)

The economic rivalry and all that do not give much offence to our people, and they admire (Germany's) steady industry and genius for organization. But they do resent mischief making. They suspect the Emperor of aggressive plans of Weltpolitik, and they see that Germany is forcing the pace in armaments in order to dominate Europe and is thereby laying a horrible burden of wasteful expenditure upon all the other powers.

(2) Kaiser Wilhelm II, interview in The Daily Telegraph (28th October 1908)

Germany is a young and growing empire. She has a world-wide commerce which is rapidly expanding and to which the legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds. Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect that commerce and her manifold interests in even the most distant seas. She expects those interests to go on growing, and she must be able to champion them manfully in any quarter of the globe. Her horizons stretch far away. She must be prepared for any eventualities in the Far East. Who can foresee what may take place in the Pacific in the days to come, days not so distant as some believe, but days at any rate, for which all European powers with Far Eastern interests ought steadily to prepare?

Look at the accomplished rise of Japan; think of the possible national awakening of China; and then judge of the vast problems of the Pacific. Only those powers that have great navies will be listened to with respect when the future of the Pacific comes to be solved; and if for that reason only, Germany must have a powerful fleet. It may even be that England herself will be glad that Germany has a fleet when they speak together on the same side in the great debates of the future.

(3) Sir Edward Grey, letter published in The Daily Telegraph (1st November, 1908)

The German Emperor is ageing me; he is like a battleship with steam up and screws going, but with no rudder, and he will run into something some day and cause a catastrophe. He has the strongest army in the world and the Germans don't like being laughed at and are looking for somebody on whom to vent their temper and use their strength. After a big war a nation doesn't want another for a generation or more. Now it is 38 years since Germany had her last war, and she is very strong and very restless, like a person whose boots are too small for him. I don't think there will be war at present, but it will be difficult to keep the peace of Europe for another five years.