The Duma

On 27th June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat infested with maggots. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov. They organized a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship. (1)

A delegation of the mutinous sailors arrived in Geneva with a message addressed directly to Father Gapon. He took the cause of the sailors to heart and spent all his time collecting money and purchasing supplies for them. He and their leader, Afanasi Matushenko, became inseparable. "Both were of peasant origin and products of the mass upheaval of 1905 - both were out of place among the party intelligentsia of Geneva." (2)

The Potemkin Mutiny spread to other units in the army and navy. Industrial workers all over Russia withdrew their labour and in October, 1905, the railwaymen went on strike which paralyzed the whole Russian railway network. This developed into a general strike. Leon Trotsky later recalled: "After 10th October 1905, the strike, now with political slogans, spread from Moscow throughout the country. No such general strike had ever been seen anywhere before. In many towns there were clashes with the troops." (3)

Sergei Witte, his Chief Minister, saw only two options open to the Tsar Nicholas II; "either he must put himself at the head of the popular movement for freedom by making concessions to it, or he must institute a military dictatorship and suppress by naked force for the whole of the opposition". However, he pointed out that any policy of repression would result in "mass bloodshed". His advice was that the Tsar should offer a programme of political reform. (4)

On 22nd October, 1905, Sergei Witte sent a message to the Tsar: "The present movement for freedom is not of new birth. Its roots are imbedded in centuries of Russian history. Freedom must become the slogan of the government. No other possibility for the salvation of the state exists. The march of historical progress cannot be halted. The idea of civil liberty will triumph if not through reform then by the path of revolution. The government must be ready to proceed along constitutional lines. The government must sincerely and openly strive for the well-being of the state and not endeavour to protect this or that type of government. There is no alternative. The government must either place itself at the head of the movement which has gripped the country or it must relinquish it to the elementary forces to tear it to pieces." (5)

Nicholas II became increasingly concerned about the situation and entered into talks with Sergi Witte. As he pointed out: "Through all these horrible days, I constantly met Witte. We very often met in the early morning to part only in the evening when night fell. There were only two ways open; to find an energetic soldier and crush the rebellion by sheer force. That would mean rivers of blood, and in the end we would be where had started. The other way out would be to give to the people their civil rights, freedom of speech and press, also to have laws conformed by a State Duma - that of course would be a constitution. Witte defends this very energetically." (6)

Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov, the second cousin of the Tsar, was an important figure in the military. He was highly critical of the way the Tsar dealt with these incidents and favoured the kind of reforms favoured by Sergi Witte: "The government (if there is one) continues to remain in complete inactivity... a stupid spectator to the tide which little by little is engulfing the country." (7)

Later that month, Trotsky and other Mensheviks established the St. Petersburg Soviet. On 26th October the first meeting of the Soviet took place in the Technological Institute. It was attended by only forty delegates as most factories in the city had time to elect the representatives. It published a statement that claimed: "In the next few days decisive events will take place in Russia, which will determine for many years the fate of the working class in Russia. We must be fully prepared to cope with these events united through our common Soviet." (8)

October Manifesto

Over the next few weeks over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia and these events became known as the 1905 Revolution. Witte continued to advise the Tsar to make concessions. The Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov agreed and urged the Tsar to bring in reforms. The Tsar refused and instead ordered him to assume the role of a military dictator. The Grand Duke drew his pistol and threatened to shoot himself on the spot if the Tsar did not endorse Witte's plan. (9)

On 30th October, the Tsar reluctantly agreed to publish details of the proposed reforms that became known as the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally it announced that no law would become operative without the approval of the State Duma. It has been pointed out that "Witte sold the new policy with all the forcefulness at his command". He also appealed to the owners of the newspapers in Russia to "help me to calm opinions". (10)

These proposals were rejected by the St. Petersburg Soviet: "We are given a constitution, but absolutism remains... The struggling revolutionary proletariat cannot lay down its weapons until the political rights of the Russian people are established on a firm foundation, until a democratic republic is established, the best road for the further progress to Socialism." (11)

State Duma

The first meeting of the Duma took place in May 1906. A British journalist, Maurice Baring, described the members taking their seats on the first day: "Peasants in their long black coats, some of them wearing military medals... You see dignified old men in frock coats, aggressively democratic-looking men with long hair... members of the proletariat... dressed in the costume of two centuries ago... There is a Polish member who is dressed in light-blue tights, a short Eton jacket and Hessian boots... There are some socialists who wear no collars and there is, of course, every kind of headdress you can conceive." (12)

Several changes in the composition of the Duma had been changed since the publication of the October Manifesto. Nicholas II had also created a State Council, an upper chamber, of which he would nominate half its members. He also retained for himself the right to declare war, to control the Orthodox Church and to dissolve the Duma. The Tsar also had the power to appoint and dismiss ministers. At their first meeting, members of the Duma put forward a series of demands including the release of political prisoners, trade union rights and land reform. The Tsar rejected all these proposals and dissolved the Duma. (13)

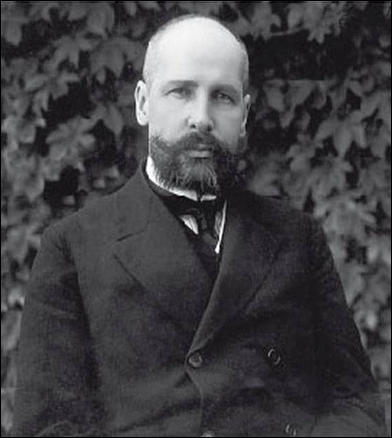

In April, 1906, Nicholas II forced Sergi Witte to resign and asked the more conservative Peter Stolypin to become Chief Minister. Stolypin was the former governor of Saratov and his draconian measures in suppressing the peasants in 1905 made him notorious. At first he refused the post but the Tsar insisted: "Let us make the sign of the Cross over ourselves and let us ask the Lord to help us both in this difficult, perhaps historic moment." Stolypin told Bernard Pares that "an assembly representing the majority of the population would never work". (14)

Stolypin attempted to provide a balance between the introduction of much needed land reforms and the suppression of the radicals. In October, 1906, Stolypin introduced legislation that enabled peasants to have more opportunity to acquire land. They also got more freedom in the selection of their representatives to the Zemstvo (local government councils). "By avoiding confrontation with peasant representatives in the Duma, he was able to secure the privileges attached to nobles in local government and reject the idea of confiscation." (15)

However, he also introduced new measures to repress disorder and terrorism. On 25 August 1906, three assassins wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his home on Aptekarsky Island. Stolypin was only slightly injured, but 28 others were killed. Stolypin's 15-year-old daughter had both legs broken and his 3-year-old son also had injuries. The Tsar suggested that the Stolypin family moved into the Winter Palace for protection. (16)

Elections for the Second Duma took place in 1907. Peter Stolypin, used his powers to exclude large numbers from voting. This reduced the influence of the left but when the Second Duma convened in February, 1907, it still included a large number of reformers. After three months of heated debate, Nicholas II closed down the Duma on the 16th June, 1907. He blamed Lenin and his fellow-Bolsheviks for this action because of the revolutionary speeches that they had been making in exile. (17)

Members of the moderate Constitutional Democrat Party (Kadets) were especially angry about this decision. The leaders, including Prince Georgi Lvov and Pavel Milyukov, travelled to Vyborg, a Finnish resort town, in protest of the government. Milyukov drafted the Vyborg Manifesto. In the manifesto, Milyukov called for passive resistance, non-payment of taxes and draft avoidance. Stolypin took revenge on the rebels and "more than 100 leading Kadets were brought to trial and suspended from their part in the Vyborg Manifesto." (18)

Stolypin's repressive methods created a great deal of conflict. Lionel Kochan, the author of Russia in Revolution (1970), pointed out: "Between November 1905 and June 1906, from the ministry of the interior alone, 288 persons were killed and 383 wounded. Altogether, up to the end of October 1906, 3,611 government officials of all ranks, from governor-generals to village gendarmes, had been killed or wounded." (19) Stolypin told his friend, Bernard Pares, that "in no country is the public more anti-governmental than in Russia". (20)

Assassination of Peter Stolypin

Peter Stolypin instituted a new court system that made it easier for the arrest and conviction of political revolutionaries. In the first six months of their existence the courts passed 1,042 death sentences. It has been claimed that over 3,000 suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906 and 1909. As a result of this action the hangman's noose in Russia became known as "Stolypin's necktie". (21)

Peter Stolypin now made changes to the electoral law. This excluded national minorities and dramatically reduced the number of people who could vote in Poland, Siberia, the Caucasus and in Central Asia. The new electoral law also gave better representation to the nobility and gave greater power to the large landowners to the detriment of the peasants. Changes were also made to the voting in towns and now those owning their own homes elected over half the urban deputies.

In 1907 Stolypin introduced a new electoral law, by-passing the 1906 constitution, which assured a right-wing majority in the Duma. The Third Duma met on 14th November 1907. The former coalition of Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, Bolsheviks, Octobrists and Constitutional Democrat Party, were now outnumbered by the reactionaries and the nationalists. Unlike the previous Dumas, this one ran its full-term of five years.

The revolutionaries were now determined to assassinate Stolypin and there were several attempts on his life. "He wore a bullet-proof vest and surrounded himself with security men - but he seemed to expect nevertheless that he would eventually die violently." The first line of his will, written shortly after he had become Prime Minister, read: "Bury me where I am assassinated." (22)

On 1st September, 1911, Peter Stolypin was assassinated by Dmitri Bogrov, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, at the Kiev Opera House. Nicholas II was with him at the time: "During the second interval we had just left the box, as it was so hot, when we heard two sounds as if something had been dropped. I thought an opera glass might have fallen on somebody's head and ran back into the box to look. To the right I saw a group of officers and other people. They seemed to be dragging someone along. Women were shrieking and, directly in front of me in the stalls, Stolypin was standing. He slowly turned his face towards me and with his left hand made the sign of the Cross in the air. Only then did I notice he was very pale and that his right hand and uniform were bloodstained. He slowly sank into his chair and began to unbutton his tunic. People were trying to lynch the assassin. I am sorry to say the police rescued him from the crowd and took him to as isolated room for his first examination." (23)

First World War

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War the Duma voted to support Nicholas II and his government. When the five Bolshevik deputies voted against the government on this issue, they were arrested, had their property confiscated and after being charged with subversion were sentenced to Siberian exile. (24)

As Nicholas II was supreme command of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline in his support in Russia. George Buchanan, the British Ambassador in Russia, went to see the Tsar: "I went on to say that there was now a barrier between him and his people, and that if Russia was still united as a nation it was in opposing his present policy. The people, who have rallied so splendidly round their Sovereign on the outbreak of war, had seen how hundreds of thousands of lives had been sacrificed on account of the lack of rifles and munitions; how, owing to the incompetence of the administration there had been a severe food crisis."

Buchanan then went on to talk about Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna: "I next called His Majesty's attention to the attempts being made by the Germans, not only to create dissension between the Allies, but to estrange him from his people. Their agents were everywhere at work. They were pulling the strings, and were using as their unconscious tools those who were in the habit of advising His Majesty as to the choice of his Ministers. They indirectly influenced the Empress through those in her entourage, with the result that, instead of being loved, as she ought to be, Her Majesty was discredited and accused of working in German interests." (25)

In January 1917, General Aleksandr Krymov returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma. Krymov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. "A revolution is imminent and we at the front feel it to be so. If you decide on such an extreme step (the overthrow of the Tsar), we will support you. Clearly there is no other way." Rodzianko was unwilling to take action but he did telegraph the Tsar warning that Russia was approaching breaking point. He also criticised the impact that his wife was having on the situation and told him that "you must find a way to remove the Empress from politics". (26)

The Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich shared the views of Rodzianko and sent a letter to the Tsar: "The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs." (27)

The President of the Duma, Michael Rodzianko, became very concerned about the situation in the city and sent a telegram to the Tsar: "The situation is serious. There is anarchy in the capital. The Government is paralysed. Transport, food, and fuel supply are completely disorganised. Universal discontent is increasing. Disorderly firing is going on in the streets. Some troops are firing at each other. It is urgently necessary to entrust a man enjoying the confidence of the country with the formation of a new Government. Delay is impossible. Any tardiness is fatal. I pray God that at this hour the responsibility may not fall upon the Sovereign." (28)

On 10th March, 1917, the Tsar had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that Nicholas II should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed." (29)

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government. Members of the Cabinet included Pavel Milyukov (leader of the Cadet Party), was Foreign Minister, Alexander Guchkov, Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, Mikhail Tereshchenko, a beet-sugar magnate from the Ukraine, became Finance Minister, Alexander Konovalov, a munitions maker, Minister of Trade and Industry, and Peter Struve, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The Duma was closed down after the Bolshevik Revolution in October, 1917.

Primary Sources

(1) Sergei Witte, letter to Nicholas II (22nd October, 1905)

The present movement for freedom is not of new birth. Its roots are imbedded in centuries of Russian history. 'Freedom' must become the slogan of the government. No other possibility for the salvation of the state exists. The march of historical progress cannot be halted. The idea of civil liberty will triumph if not through reform then by the path of revolution.

The government must be ready to proceed along constitutional lines. The government must sincerely and openly strive for the well-being of the state and not endeavour to protect this or that type of government. There is no alternative. The government must either place itself at the head of the movement which has gripped the country or it must relinquish it to the elementary forces to tear it to pieces.

(2) Felix Yusupov was opposed to the power given to the Duma in 1906.

In 1906 strikes broke out almost everywhere; there were several attempts on the lives of members of the Imperial family and of high government officials. The Tsar was forced to compromise and give the country a constitutional government by establishing the Duma. The Tsarina violently opposed this; she did not realize the seriousness of the situation, and would not admit that there was no other solution.

The Duma opened on April 27th, 1906. This was a moment of great anxiety for all, as everyone knew the Duma was a two-edged sword which could prove either helpful or disastrous to Russia, according to the course of events.

If all members of the Duma had been loyal Russians actuated only by patriotic motives, the Assembly might have done great service to the Government; but certain questionable and destructive elements - among which were many Jews - made it a hotbed of revolutionary ideas.

(3) David Shub was a member of the Social Democratic Party when Peter Stolypin was in power.

Stolypin began to look for an excuse to dissolve the Duma and the Bolsheviks furnished him with one. Lenin insisted that the deputies use their parliamentary immunity to agitate for an armed uprising.

Years later it was discovered that these secret Bolshevik cells were infested with agents of the secret police. By keeping a sharp eye on the Social Democratic deputies, these stool pigeons were able to frame the deputies on the charges of inciting rebellion, thus giving Stolypin his excuse.

(4) Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma, telegram to Nicholas II (27th February, 1917)

The situation is growing worse. Measures should be taken immediately as tomorrow will be too late. The last hour has struck, when the fate of the country and dynasty is being decided.

The government is powerless to stop the disorders. The troops of the garrison cannot be relied upon. The reserve battalions of the Guard regiments are in the grips of rebellion, their officers are being killed. Having joined the mobs and the revolt of the people, they are marching on the offices of the Ministry of the Interior and the Imperial Duma.

Your Majesty, do not delay. Should the agitation reach the Army, Germany will triumph and the destruction of Russian along with the dynasty is inevitable.

(5) David Shub, Lenin (1948)

In the early days the Soviet set for itself the task of spreading and consolidating the revolutionary gains and fighting military and ideological attacks from the Right. The Soviet was not a conventional parliamentary body. It functioned from day to day, without set rules. Its membership soon reached 2,000; by the middle of March it had 3,000 delegates.

It was to the Soviet that Rodzianko appealed for permission to secure a train to see the Tsar; it was the Soviet that stopped the general strike, reopened the factories and restored streetcar traffic.

At the Duma the situation was still chaotic. No one knew what would happen next. Kerensky and Chkheidze, accompanied by several other Socialist deputies, took a bold chance. They appeared on the streets and made a direct appeal to the soldiers to join the rebellion. The soldiers responded.

With their mandate from the Petrograd Soviet, Kerensky and Chkheidze now persuaded the majority of the Duma to elect a Provisional Committee to take over the reins of government. Both became members of this committee.

The walls of the city were plastered with the first issue of Izvestia, calling on the people to complete the overthrow of the Tsarist regime and pave the way for a democratic government.

"The fight must go on to the end. The old powers must be completely overthrown to make way for popular government. All together, with our forces united we shall battle to wipe out completely the old government and call a Constituent Assembly", the proclamation read.

The Tsar's Council of Ministers now offered to disband and to instruct Prince George Lvov or Rodzianko to form a new cabinet. Frantically Grand Duke Mikhail telephoned Chief of Staff General Alexeyev, asking him to make an eleventh-hour appeal to the Emperor to grant a responsible Ministry. The Tsar replied that he was grateful for his brother's advice but would do nothing of the kind. He did not know that the Duma conservatives were already swept into the background by the revolutionary masses of workers and soldiers.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)