The Popular Front

On 15th January 1936, Manuel Azaña helped to establish a coalition of parties on the political left to fight the national elections due to take place the following month. This included the Socialist Party (PSOE), Communist Party ( PCE), Esquerra Party and the Republican Union Party.

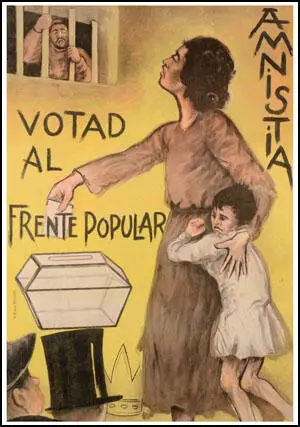

The Popular Front, as the coalition became known, advocated the restoration of Catalan autonomy, amnesty for political prisoners, agrarian reform, an end to political blacklists and the payment of damages for property owners who suffered during the revolt of 1934. The Anarchists refused to support the coalition and instead urged people not to vote.

Right-wing groups in Spain formed the National Front. This included the CEDA and the Carlists. The Falange Española did not officially join but most of its members supported the aims of the National Front.

The Spanish people voted on Sunday, 16th February, 1936. Out of a possible 13.5 million voters, over 9,870,000 participated in the 1936 General Election. 4,654,116 people (34.3) voted for the Popular Front, whereas the National Front obtained 4,503,505 (33.2) and the centre parties got 526,615 (5.4). The Popular Front, with 263 seats out of the 473 in the Cortes formed the new government.

The Popular Front government immediately upset the conservatives by releasing all left-wing political prisoners. The government also introduced agrarian reforms that penalized the landed aristocracy. Other measures included transferring right-wing military leaders such as Francisco Franco to posts outside Spain, outlawing the Falange Española and granting Catalonia political and administrative autonomy.

As a result of these measures the wealthy took vast sums of capital out of the country. This created an economic crisis and the value of the peseta declined which damaged trade and tourism. With prices rising workers demanded higher wages. This led to a series of strikes in Spain.

On the 10th May 1936 the conservative Niceto Alcala Zamora was ousted as president and replaced by the left-wing Manuel Azaña. Soon afterwards Spanish Army officers began plotting to overthrow the Popular Front government.

President Manuel Azaña appointed Diego Martinez Barrio as prime minister on 18th July 1936 and asked him to negotiate with the rebels. He contacted Emilio Mola and offered him the post of Minister of War in his government. He refused and when Azaña realized that the Nationalists were unwilling to compromise, he sacked Martinez Barrio and replaced him with José Giral. To protect the Popular Front government, Giral gave orders for arms to be distributed to left-wing organizations that opposed the military uprising.

General Emilio Mola issued his proclamation of revolt in Navarre on 19th July, 1936. The coup got off to a bad start with José Sanjurjo being killed in an air crash on 20th July. The uprising was a failure in most parts of Spain but Mola's forces were successful in the Canary Islands, Morocco, Seville and Aragon. Francisco Franco, now commander of the Army of Africa, joined the revolt and began to conquer southern Spain.

Manuel Azaña had no desire to be head of a government that was trying to militarily defeat another group of Spaniards. He attempted to resign but was persuaded to stay on by the Socialist Party and Communist Party who hoped that he was the best person to persuade foreign governments not to support the military uprising.

In September 1936, President Azaña appointed the left-wing socialist, Francisco Largo Caballero as prime minister. Largo Caballero also took over the important role of war minister. Largo Caballero brought into his government two left-wing radicals, Angel Galarza (minister of the interior) and Alvarez del Vayo (minister of foreign affairs). He also included four anarchists, Juan Garcia Oliver (Justice), Juan López Sánchez (Commerce), Federica Montseny (Health) and Juan Peiró (Industry) and two right-wing socialists, Juan Negrin (Finance) and Indalecio Prieto (Navy and Air) in his government. Largo Caballero also gave two ministries to the Communist Party (PCE): Jesus Hernández (Education) and Vicente Uribe (Agriculture).

After taking power Francisco Largo Caballero concentrated on winning the war and did not pursue his policy of social revolution. In an effort to gain the support of foreign governments, he announced that his administration was "not fighting for socialism but for democracy and constitutional rule."

Largo Caballero introduced changes that upset the left in Spain. This included conscription, the reintroduction of ranks and insignia into the militia, and the abolition of workers' and soldiers' councils. He also established a new police force, the National Republican Guard. He also agreed for Juan Negrin to be given control of the Carabineros.

Largo Caballero came under increasing pressure from the Communist Party to promote its members to senior posts in the government. He also refused their demands to suppress the Worker's Party (POUM).

By the end of September 1936, the generals involved in the military uprising came to the conclusion that Francisco Franco should become commander of the Nationalist Army. He was also appointed chief of state. General Emilio Mola agreed to serve under him and was placed in charge of the Army of the North.

Franco now began to remove all his main rivals for the leadership of the Nationalist forces. Some were forced into exile and nothing was done to help rescue José Antonio Primo de Rivera from captivity. However, when José Antonio was shot by the Republicans in November 1936, Franco exploited his death by making him a mythological saint of the fascist movement.

On 19th April 1937, Franco forced the unification of the Falange Española and the Carlists with other small right-wing parties to form the Falange Española Tradicionalista. Franco then had himself appointed as leader of the new organisation. Imitating the tactics of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, giant posters of Franco and the dead José Antonio were displayed along with the slogan, "One State! One Country! One Chief! Franco! Franco! Franco!" all over Spain.

During the Spanish Civil War the National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT), the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and the Worker's Party (POUM) played an important role in running Barcelona. This brought them into conflict with other left-wing groups in the city including the Union General de Trabajadores (UGT), the Catalan Socialist Party (PSUC) and the Communist Party (PCE).

On the 3rd May 1937, Rodriguez Salas, the Chief of Police, ordered the Civil Guard and the Assault Guard to take over the Telephone Exchange, which had been operated by the CNT since the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. Members of the CNT in the Telephone Exchange were armed and refused to give up the building. Members of the CNT, FAI and POUM became convinced that this was the start of an attack on them by the UGT, PSUC and the PCE and that night barricades were built all over the city.

Fighting broke out on the 4th May. Later that day the anarchist ministers, Federica Montseny and Juan Garcia Oliver, arrived in Barcelona and attempted to negotiate a ceasefire. When this proved to be unsuccessful, Juan Negrin, Vicente Uribe and Jesus Hernández called on Francisco Largo Caballero to use government troops to takeover the city. Largo Caballero also came under pressure from Luis Companys not to take this action, fearing that this would breach Catalan autonomy.

On 6th May death squads assassinated a number of prominent anarchists in their homes. The following day over 6,000 Assault Guards arrived from Valencia and gradually took control of Barcelona. It is estimated that about 400 people were killed during what became known as the May Riots.

These events in Barcelona severely damaged the Popular Front government. Communist members of the Cabinet were highly critical of the way Francisco Largo Caballero handled the May Riots. President Manuel Azaña agreed and on 17th May he asked Juan Negrin to form a new government. Negrin was a communist sympathizer and from this date Joseph Stalin obtained more control over the policies of the Republican government.

Negrin's government now attempted to bring the Anarchist Brigades under the control of the Republican Army. At first the Anarcho-Syndicalists resisted and attempted to retain hegemony over their units. This proved impossible when the government made the decision to only pay and supply militias that subjected themselves to unified command and structure.

Negrin also began appointing members of the Communist Party (PCE) to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history."

Negrin now attempted to gain the support of western governments by announcing his plan to decollectivize industries. On 1st May 1938 Negrin published a thirteen-point program that included the promise of full civil and political rights and freedom of religion.

In August 1938 President Manuel Azaña attempted to oust Juan Negrin. However, he no longer had the power he once had and with the support of the communists in the government and armed forces, Negrin was able to survive.

On 26th January, 1939, Barcelona fell to the Nationalist Army. Azaña and his government now moved to Perelada, close to the French border. With the nationalist forces still advancing, Azaña and his colleagues crossed into France.

On 27th February, 1939, the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain recognized the Nationalist government headed by General Francisco Franco. Later that day Manuel Azaña resigned from office, declaring that the war was lost and that he did not want Spaniards to make anymore useless sacrifices.

Juan Negrin now promoted communist leaders such as Antonio Cordon, Juan Modesto and Enrique Lister to senior posts in the army. Segismundo Casado, commander of the Republican Army of the Centre, now became convinced that Negrin was planning a communist coup. On 4th March, Casedo, with the support of the socialist leader, Julián Besteiro and disillusioned anarchist leaders, established an anti-Negrin National Defence Junta.

On 6th March José Miaja in Madrid joined the rebellion by ordering the arrests of Communists in the city. Negrin, about to leave for France, ordered Luis Barceló, commander of the First Corps of the Army of the Centre, to try and regain control of the capital. His troops entered Madrid and there was fierce fighting for several days in the city. Anarchists troops led by Cipriano Mera, managed to defeat the First Corps and Barceló was captured and executed.

Segismundo Casado now tried to negotiate a peace settlement with General Francisco Franco. However, he refused demanding an unconditional surrender. Members of the Republican Army still left alive, were no longer willing to fight and the Nationalist Army entered Madrid virtually unopposed on 27th March. Four days later Francisco Franco announced the end of the Spanish Civil War.

Primary Sources

(1) Charlotte Haldane visited Spain with John Haldane in 1933. Charlotte later wrote about their experiences in her autobiography, Truth Will Out (1949)

The poverty was tragic. It was bad in Cordoba, worse in Granada, almost universal in Seville. Everywhere was economic, mental and physical depression. There was a lot of local opposition to the Republic, led and organized by the Church. The Government's natural idealistic incompetence was encouraged by systematic sabotage of every project attempted. The male working population was almost unanimously anarchist. The CNT and particularly the FAI were the strongest revolutionary parties. Socialism and Communism, or rather the Trotskyist deviation from that political creed, were in the minority. But almost the entire female population was firmly attached to Church politics, under the spiritual and political domination of the priesthood. Underneath all the beauty and glamour of the landscape, the architecture, the tradition, the romance, were rumblings of the political earthquake to come.

(2) Luis Bolin, Spain, the Vital Years (1967)

On 16 November 1935, as a prelude to Communist rule, the Comintern instructed Spanish party members to join hands with Socialist and Left-wing Republicans. Without antagonizing the middle classes, they were to intensify their campaign of violence against the Church and the Right and maintain peasants and other workers in constant turmoil and unrest. These instructions were scrupulously executed during the months that followed.

The tactics thus propounded were not new. Lenin had already prophesied that Spain would be the first country after Russia to adopt Communism. Trotsky shared this opinion.

(3) Edward Knoblaugh, Correspondent in Spain (1937)

Zamora felt he had no alternative except to dissolve the Cortes and call for new elections. He issued the decree on January 7, 1936. The elections were set for February 16. That act was his political death warrant. Three months later to the day he was ousted from office.

Azana, meanwhile, had been in eclipse. Out of the political limelight, his name had been heard only for a brief moment since the fall of 1933. That was when he appeared in the Cortes chamber and, by a masterful defense, saved himself from going to prison as an alleged accomplice of Company's in the Barcelona revolt of October, 1934. He had been in Barcelona before and during the uprising, and had held numerous conferences with Companys. His defense was one of the finest bits of oratory I have ever heard.

It had its effect, and Azana was exonerated. Now he blossomed out in a new role—one that was to carry him to the Presidency. He organized the Left Popular Front. Socialists, Anarchists, Communists and Left Republicans were summoned to his banner. The Rightists vowed that it could not be done, but Azana welded the groups. The feat earned him the admiration of even his bitterest enemies. The Socialists and Communists had reached an entente, but the Left Republicans and the Anarchists were as far apart as the stars, and they in turn had nothing in common with the Socialist-Communists. In getting these discordant elements together Azana lived up to his reputation as the shrewdest and cleverest politician in Spain.

(4) Francisco Largo Caballero, speech in Madrid (March 1936)

The illusion that the proletarian socialist revolution can be achieved by reforming the existing state must be eliminated. There is no course but to destroy its roots. Imperceptibly, the dictatorship of the proletariat or workers' democracy will be converted into a full democracy, without classes from which the coercive state will gradually disappear. The instrument of the dictatorship will be the Socialist party, which will exercise this dictatorship during the period of transition from one society to another and as long as the surrounding capitalist states make a strong proletarian state necessary.

(5) Roy Campbell, Light on a Dark Horse (1951)

One noticed, during the restless period that preceded the 1936 elections, that the working class was divided in two.

The bootblacks, an enormous class to themselves in Spain, the waiters, and most of the mechanics, along with the miners and factory workers, were either anarchists or Reds. It was expected that the anarchists would abstain from voting: or might even vote for the Right, with whom, in their liking for liberty, they have more in common than with the Communists. Amongst the anarchists were to be found some of the most generous idealistic people, at the same time as the real "phonys" - like the ones that dug up the cemetery in Huesca, held parades of naked nuns, and out-babooned in atrocity anything I had ever read of before. But they were warm-blooded - unlike their ice-cold compéres, the "commies", who were less human. You could beg your life from an anarchist. It was not long before most of the anarchists wished they had gone Right for they were unmercifully massacred by their Red Comrades.

Hostilities broke out between Anarchists and other Republicans simultaneously with their persecution of Christians, Royalists, and Nationalists. That was one of the typical paradoxes of Spanish history during the last twenty years. It was because I saw this fission, so often, at first-hand, on the spot, that I knew and said, repeatedly, and without ever hypocritically turning in my tracks, that the mutual loathing of the various factions of "republicans" would eventually preponderate over their hostility to the common adversary, and the so called "loyalists" would collapse on account of mutual disloyalty.

(6) Salvador de Madariaga, a member of the Republican Union Party, commented on the clash between Largo Caballero and Indalecio Prieto.

What made the Spanish Civil War inevitable was the civil war within the Socialist party. No wonder Fascism grew. Let no one argue that it was fascist violence that developed socialist violence. It was not at the Fascists that Largo Caballero's gunmen shot but at their brother socialists. It was (Largo Caballero's) avowed, nay, his proclaimed policy to rush Spain on to the dictatorship of the proletariat. Thus pushed on the road to violence, the nation, always prone to it, became more violent than ever. This suited the fascists admirably, for they are nothing if not lovers and adepts of violence.

(7) Luis Bolin, Spain, the Vital Years (1967)

Alcala Zamora was kicked out for dismissing the Cortes unconstitutionally, though he had acted thus - not unwillingly - at the behest of those who ejected him. Azana was elected his successor. No worthier candidate for the Presidency of such a Republic could have been found. His most unprincipled adherent, Casares Quiroga, was appointed Premier and Minister of War. Other posts in the Cabinet were allotted to Republican Left, Republican Union and Catalan Left, willing pawns of the Red extremists, who, for the time being, directed operations from the wings. Revolt broke out in a dozen towns, and outrages were committed daily in Barcelona, Malaga, Saragossa, Granada, Bilbao and Seville. In Madrid, a riot was caused by a preposterous rumour to the effect that ladies who worked for social welfare had distributed poisoned sweets to children. As a reprisal several churches were burnt and three nuns and two other women, one of them of French nationality, were assaulted and almost lynched by an infuriated mob.

(8) A member of the Labour Party, Emanuel Shinwell initially argued that the British government should give support to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about his views in his autobiography, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

When the Spanish Republican Government was formed in 1936 the news was received enthusiastically by Socialists in Britain. Many of the new Government members were well known in the international Socialist movement. The emergence of a democratic regime in Spain was a bright light in a gloomy period when war had raped Abyssinia, and Germany had repudiated the Locarno Treaty. On the sudden outbreak of civil war in July, 1936, Socialist movements in all those European countries where they were allowed to exist immediately took steps to consider whether intervention should be demanded.

The Fascist attack was regarded as aggression by the majority of thinking people. Leon Blum, at the time Prime Minister of France, was greatly concerned in this matter. As political head of a nation which was bordered by Spain he had to consider the danger of some of the belligerents being forced over the border; as a Socialist he had a duty to go to the help of his comrades, members of a legally elected Government, who had been attacked by men organized and financed from outside Spanish home territory.

In Britain, although the Government was against intervention, the Labour Party had to face the strong demands from the rank-and-file for concrete action. The three executives met at Transport House to consider the next move, and I was present as a member of the Parliamentary Executive. We were largely influenced by Blum's policy. He had decided that he could not risk committing his country to intervention. Germany and Italy were supplying arms, aircraft, and men to the Spanish Fascists, and Blum considered that any action on the Franco-Spanish border on behalf of the Republican Government would bring imminent danger of retaliatory moves by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany on France's eastern flank. As a result of this French attitude Herbert Morrison's appeal in favour of intervention received little support. Although, like him, I was inclined towards action I pointed out that if France failed to intervene it would be a futile gesture to advise that Britain should do so. We had the recent farce of sanctions against Italy as a warning.

(9) Claude Cockburn, The Daily Worker (25th November, 1936)

It is difficult to convey briefly and accurately the feeling for the Communist Party - so young, and until recently so small - which exists in Spain today.

It is not on the other hand, difficult to understand it.

As the situation grew tougher and tougher and more people who had previously been suspicious of, and even hostile to the Communist Party, began - sometimes rather grudgingly and sometimes "with full acknowledgments" - to accept the fact that a great many things the Communists had said, which seemed sensational or alarmist at the time, were, as a matter of fact, true: that when the Communists talked about the "need for unity" they really were talking about a matter of life and death, as obvious and urgent as the provision of machine-gun ammunition and sandbags: that when the Communists declared that every other political consideration must be secondary to the question of how to win the war, they meant just that: that when they called upon others to subordinate sectional aims to the need for supporting the democratic government of Spain against the Fascists they were the first to put their propositions into practice: and above all, that, as a result of their highly disciplined yet highly democratic form of organisation, they were able more easily than any other single organisation to translate intentions into action.

Of course it would be possible to put all this in a more formal way, and a full analysis of the work of the Communist Party in the united defence of Spain by all the parties of the People's Front would be a very valuable thing.

Here, since the part being played by the Communist Party in the defence of Madrid is now in the centre of the world stage, I only want to draw attention to one or two of the points which have brought the Communist Party to this immensely responsible and honourable position in the democratic alliance, where it shares with Socialists, Republicans, anarchists and Catholics, the task of holding the front line of the world's democracy against the world Fascist threat.

It is, for instance, no secret that the very first move for the creation of the People's Army of Spain came from the Communist Party. Nor did it come simply in the form of a "suggestion" or a manifesto or a report.

(10) Manuel Azaña, speech (21st January, 1937)

I believe in the creations that will emerge from this tremendous upheaval in Spain. The regime that I desire is one where all the rights of conscience and of the human person are defended and secured by all the political machinery of the State, where the moral and political liberty of man is guaranteed, where work shall be, as the Republic intended it to be in Spain, the one qualification of Spanish citizenship, and where the free disposal of their country's destiny by the people in their entirety and in their total representation is assured. No regime will be possible in Spain unless its based on what I have just said. Peace will come, and the victory will come; but it will be an impersonal victory: the victory of the law, of the people, the victory of the Republic. It will not be a triumph of a leader, for the Republic has no chiefs, and because we are not going to substitute for the old oligarchic and authoritarian militarism a demagogic and tumultuous militarism, more fatal still and even more ineffective in the professional sphere. Victory will be impersonal, for it will not be the triumph of any one of us, or of our parties, or of our organizations. It will be the triumph of Republican liberty, the triumph of the rights of the people, of the moral entities before which we bow.

(11) Manuel Azaña, speech (18th July, 1937)

It is therefore an evident truth that if the war in Spain has now lasted a year, it is no longer a movement of repression against an internal rebellion, but an act of war from without, an invasion. The war is entirely and exclusively maintained, not by the military rebels, but by the Foreign Powers that are making a clandestine invasion of the Spanish Republic.

Spain has been invaded by three Powers: Portugal, Italy and Germany. What, then, are the motives of this three-fold invasion? The internal political regime of Spain does not matter greatly to them, and even if it mattered, would not justify the invasion. No. They have come for our mines, they have come for our raw materials, they have come for harbours, for the Straits, for naval bases in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. What is the purpose of all this? To check the Western Powers who are interested in maintaining this balance and in whose international political orbit. Spain has moved for many decades. To check both the British Power and the French. That is the reason for the invasion of Spain.

(12) Bill Bailey wrote to his mother explaining why he was fighting in the Spanish Civil War (1937)

You see Mom, there are things that one must do in this life that are a little more than just living. In Spain there are thousands of mothers like yourself who never had a fair shake in life. They got together and elected a government that really gave meaning to their life. But a bunch of bullies decided to crush this wonderful thing. That's why I went to Spain, Mom, to help these poor people win this battle, then one day it would be easier for you and the mothers of the future. Don't let anyone mislead you by telling you that all this had something to do with Communism. The Hitlers and Mussolinis of this world are killing Spanish people who don't know the difference between Communism and rheumatism. And it's not to set up some Communist government either. The only thing the Communists did here was show the people how to fight and try to win what is rightfully theirs.

(13) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

The Government was headed by Caballero, a Left-wing Socialist, and contained ministers representing the U.G.T. (Socialist trade unions) and the C.N.T. (Syndicalist unions controlled by the Anarchists). The Catalan Generalite was for a while virtually superseded by an anti-Fascist Defence Committee' consisting mainly of delegates from the trade unions. Later the Defence Committee was dissolved and the Generalite was reconstituted so as to represent the unions and the various Left-wing parties. But every subsequent reshuffling of the Government was a move towards the Right. First the P.O.U.M. was expelled from the Generalite; six months later Caballero was replaced by the Right-wing Socialist Negrin; shortly afterwards the C.N.T. Was eliminated from the Government; then the U.G.T.; then the C.N.T. Was turned out of the Generalite; finally, a year after the outbreak of war and revolution, there remained a Government composed entirely of Right-wing Socialists, Liberals, and Communists.

(14) Franz Borkenau, Spanish Cockpit: An Eyewitness Account of the Political and Social Conflicts of the Political and Social Conflicts of the Spanish Civil War (1937)

In the afternoon I attended, in Valencia, a mass meeting of the Popular Front (to which neither the anarchists nor POUM belong). There were about 50,000 enthusiastic people there. When La Pasionaria appeared on the platform enthusiasm reached its climax. She is the one communist leader who is known and loved by the masses, but in compensation there is no other personality in the Government camp loved and admired so much. And she deserves her fame. It is not that she is politically minded. On the contrary, what is touching about her is precisely her aloofness from the atmosphere of political intrigue: the simple, self-sacrificing faith which emanates from every word she speaks. And more touching even is her lack of conceit, and even her self-effacement. Dressed in simple black, cleanly and carefully but without the slightest attempt to make herself look pleasant, she speaks simply, directly, without rhetoric, without caring for theatrical

effects, without bringing political sous-entendus into her speech, as did all the other speakers of the day. At the end of her speech came a pathetic moment. Her voice, tired from endless addresses to enormous meetings since the beginning of the civil war, failed her. And she sat down with a sad waving gesture of her hands, wanting to express: 'It's no use, I can't help it, I can't say any more; I am sorry.' There was not the slightest touch of ostentation in it, only regret at being unable to tell the meeting those things she had wanted to tell it. This gesture, in its profound simplicity, sincerity, and its convincing lack of any personal interest in success or failure as an orator, was more touching than her whole speech. This woman, looking fifty with her forty years, reflecting, in every word and every gesture, a profound motherliness (she has five children herself, and one of her daughters accompanied her to the meeting), has something of a medieval ascetic, of a religious personality about her. The masses worship her, not for her intellect, but as a sort of saint who is to lead them in the days of trial and temptation.

(15) Manuel Azaña, speech (13th November, 1937)

We are fighting in self-defense, defending the life of our people and its highest moral values, all the moral values of Spain, absolutely all - the past, the present, and those that you will know how to create in time to come.

We, the innovators of Spanish policy, we, the restorers of the Republic, the workmen of the Republic, who labored to make it an instrument to bring civilization and progress to our community, we have denied nothing of all that is noble and great in the history of Spain - absolutely nothing.

(16) Clement Attlee, statement in the House of Commons on the British government's decision to recognize General Franco's government (27th February, 1939)

We see in the action a gross betrayal of democracy, the consummation of two and a half years of the hypocritical pretence of nonintervention and a connivance all the time at aggression. And this is only one step further in the downward march of His Majesty's government in which at every stage they do not sell, but give away, the permanent interest of this country. They do not do anything to build up peace or stop war, but merely announce to the whole world that anyone who is out to use force can always be sure that he will have a friend in the British Prime Minister.

(17) Statement by the Anti-Negrin National Defence Junta (5th March, 1939)

Spanish workers, people of anti-fascist Spain! The time has come when we must proclaim to the four winds the truth of our present situation. As revolutionaries, as proletarians, as Spaniards, as anti-fascists, we cannot endure any longer the imprudence and the absence of forethought of Dr. Negrin's government. We cannot permit that, while the people struggle, a few privileged persons should continue their life abroad. We address all workers, antifascists and Spaniards! Constitutionally, the government of Dr Negrin is without lawful basis. In practice also, it lacks both confidence and good sense. We have come to show the way which may avoid disaster: we who oppose the policy of resistance give our assurance that not one of those who ought to remain in Spain shall leave till all who wish to leave have done so.

(18) Manuel Portela Valladares, the Spanish prime minister between 30th December 1935 and 19th February 1936, was interviewed in Barcelona on 8th January 1938.

My opinion is that the Republican army is stronger than the rebel army. I said this three months ago, and now the capture of Teruel has proved it to the world. The northern front collapsed because it was technically impossible to defend, because it lacked unity of command, and because it was geographically inaccessible. In spite of his 80,000 Italians and 10,000 Germans, in spite of all the supplies provided by these two great nations, Franco is now being defeated because he has aroused the spirit of independence in the Spanish people.

Ten thousand officers are graduating from the Republican academies each year. War production has been organised. The Republican command, which contains 6,000 officers belonging to the former Spanish army, has growing intelligence and technical services. But nothing is more tremendous than the spirit of resistance which has withstood all defeats. The war of the Republic is only now beginning. The Negrin Government has restored order in Republican Spain to such a degree that the percentage of crimes is lower than ever before. It has instituted full and normal constitutional law and respect for this law.

Expression of opinion in the press is even allowed a scope that I consider excessive in time of war. The leaders of Spanish public opinion surely ought all to realise the necessity of giving Spain a Westphalian peace as far as religion is concerned, a political peace based on the existing Constitution, and a social peace which consolidates the genuine advances made up to the present time.

On the rebel side a national syndicalism has been built up which, according to its official programme, is much more damaging to property and a greater menace to capitalism. And cruelty and barbarism have reached limits hitherto unknown.

On February 17, 1936, in view of the victory of the People's Front, the Right wing leaders came to me and begged me to become Dictator, and that very day General Franco offered me the Dictatorship for myself personally. Again, on the 19th Franco and the others insisted on this. I refused and agreed to resign, so as to hand over the government to the People's Front. The Right wing leaders had remained in Parliament until the civil war: they collaborated in the working of that Parliament, and thus acknowledged the validity of its power.

(19) Edward Heath, The Course of My Life (1988)

In the summer of 1938, together with three other Oxford undergraduates, I received an invitation from the Republican government of Spain, which had then been involved for nearly two years in its civil war, to spend two or three weeks in Catalonia, the last great province remaining under its control. I was invited in my capacity as chairman of the Federation of University Conservative Associations. My colleagues were Richard Symonds, a socialist from Corpus Christi who joined the United Nations secretariat after the Second World War; Derek Tasker, a Liberal from Exeter College who was later ordained and became the Canon Treasurer of Southwark Cathedral; and George Stent, a South African from Magdalen, who was probably the furthest to the left of us all in his political views. For all of us, it was to be our first taste of war.

We were to witness a conflict which aroused, in our generation, passions every bit as fierce as those stirred up by the war in Vietnam thirty years later. The struggle between the Republicans and General Franco's fascists had gained particular international significance because of the intervention of Germany and Italy on Franco's side, and the refusal of the Chamberlain government to do more than isolate Spain. Moreover, many of our contemporaries had gone off to Spain to fight, the majority on the Republican side, and many had lost their lives. My sympathies were firmly with the elected government of the Spanish Republic simply because it was not a dictatorship, although it was somewhat to the left and was supported by the Soviet Union.

The base for our visit was Barcelona, and we travelled there via Calais, Paris and Perpignan. At one point, our night train came to a juddering halt. Opening the window, we discovered that a wheel had come off, but not from our carriage. We arrived late at Perpignan, our destination in France. After a superb lunch in a restaurant overlooking the main square of the town, we were then driven at breakneck speed along the coast, a lot of it at quite a height, on the winding mountain roads down to Barcelona. We found the capital city of Catalonia in darkness - it was never lit up for fear of air-raids - and settled in to a comfortable hotel. Instructions in our rooms told us to go down to the basement in the event of an air-raid alarm. It was just as well that we did not heed those instructions, opting instead for the excitement of watching the bombers flying past. During one raid, a bomb went straight down the hotel lift shaft, skittling to the bottom and killing all those who had rushed down to the basement shelter.

(20) Jane Patrick, CNT-FAI radio broadcast (29th March, 1937)

What do you think of the situation in Spain now? Do you think that the revolution is progressing? For my part I see it slipping, slipping, and that has been the position for some time. However, perhaps it will be possible for it to be saved. Let us hope so, but it seems to me that reaction is gaining a stronger hold each day. What do you expect Britain and France to do about Italy, now that she has so openly declared her intentions? Do you think they will rush an armistice or will they just let things slide? In my opinion they cannot afford to let things slide as there is no limit to what the Duce will do, and I don't think they will be prepared to declare war, so the only alternative, so as as I can see, is an armistice. I think an armistice would be a disgraceful thing, and the Anarchists of Spain would not stand for it. But I am afraid the government cannot be trusted. The government and its Communist Party allies are capable of anything. What will follow? Of course, I do not know what will take place. It is all speculation on my part but things seem to me to be in a very bad way.