Yevgeni Zamyatin

Yevgeni Zamyatin was born in Lebedyan, Russia, on 20th January, 1884. The son of a teacher, Zamyatin trained as a naval engineer at St Petersburg. While a student joined the Bolshevik faction of the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). He later wrote: "To be a Bolshevik in those years meant following the path of greatest resistance, so I was a Bolshevik then."

Zamyatin's support of the Bolsheviks resulted in him being arrested and sent into exile. He returned during the 1905 Revolution and joined the student demonstrations against Nicholas II. Zamyatin was arrested, badly beaten and sent to Spalernaja Prison where he had to endure several months of solitary confinement.

After graduating Zamyatin became a lecturer at the Department of Naval Architecture. He wrote several articles on ship construction for journals such as The Ship and Russian Navigation. He also wrote fiction and in 1913 published the novel A Provincial Tale. This was followed by At The World's End (1914), a satire on military life. This upset the censors and Zamyatin was brought to trial but was acquitted. However, the book was banned and all copies were destroyed.

During the First World War Zamyatin was sent to England to supervise the building of Russian icebreakers. He returned to Russia after the October Revolution. Although initially a supporter of the Bolsheviks he began to question the new government's attempt to control the arts.

Zamyatin switched his support to the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and published a series of political fables in Delo Naroda (The People's Concern), a newspaper run by Victor Chernov. He also wrote for Novaya Zhizn (New Life) a journal funded and edited by Maxim Gorky. In one of these articles he attacked the Soviet government and its Red Terror.

In 1919 Zamyatin was recruited by Maxim Gorky to work with him on his World Literature project. It was the task of Gorky, Zamyatin, Alexander Blok, Nikolai Gumilev, and other members of the editorial board to select, translate and publish non-Russian literary works. Each volume was to be annotated, illustrated, and supplied with an introductory essay.

Ignoring warnings about the dangers of what he was doing, Zamyatin published the essay, I Am Afraid, where he argued that the attitude of those in authority was stifling creative literature. "Russian writers are accustomed to going hungry. The main reason for their silence is not lack of bread or lack of paper; the reason is far weightier, far tougher, far more ironclad. It is that true literature can exist only where it is created, not by diligent and trustworthy officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels and skeptics."

Zamyatin continued to write fiction and literary criticism and in 1921 his work inspired the creation of Serapion Brothers. The group argued for greater freedom and variety in literature. Members included Nickolai Tikhonov, Mikhail Slonimski, Vsevolod Ivanov and Konstantin Fedin.

In 1923 Zamyatin published Fires of St. Dominic, a book about the Spanish Inquisition, that parallels the activities of the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. He also wrote a series of plays including the popular Attilla. It was through his work with World Literature that Zamyatin discovered the science fiction of H. G. Wells. This inspired him to write the novel We. The first anti-utopian novel ever written, it is a satire on life in a collectivist state in the future. People in this new society called One State, have numbers rather than names, wear identical uniforms and live in buildings built of glass. The people are ruled by the Benefactor and policed by the Guardians. One State is surrounded by a wall of glass and outside is an untamed green jungle.

The hero of We is D-503, a mathematician who is busy building Integral, a gigantic spaceship which will eventually go to other planets to spread the joy of the One State. D-503 is happy with his life until he falls in love with I-330, a member of Mephi, a revolutionary organization living in the jungle. D-503 now joins the plot to take over Integral and use it as a weapon to destroy One State. However, the conspirators are arrested by the Guardians and the Benefactor decides that action must be taken to prevent further revolts. D-503 like the rest of the people living in One State, is forced to undergo the Great Operation, which destroys the part of the brain which controls passion and imagination.

Zamyatin secretly distributed copies of We through literary circles. He was warned by friends that attempts to publish the book in the Soviet Union would led to his arrest and possible execution. Zamyatin knew that he could not be published in the Soviet Union but he managed to smuggle a copy of his manuscript abroad. An English translation of the novel was published in the United States in 1924. Three years later a Russian language edition began to circulate in Eastern Europe.

The publication of We brought fierce criticism from the Soviet Writers' Union. He responded by resigning with the comment that "I find it impossible to belong to a literary organization which, even if only indirectly, takes a part in the persecution of a fellow member."

Zamyatin's plays were banned from the theatre and any books that had been published in the Soviet Union were confiscated. Zamyatin described these events as a "writer's death sentence" and wrote to Joseph Stalin requesting to emigrate claiming that "no creative activity is possible in an atmosphere of systematic persecution that increases in intensity from year to year." He bravely added: " Regardless of the content of a given work, the very fact of my signature has become a sufficient reason for declaring the work criminal. Of course, any falsification is permissible in fighting the devil. I beg to be permitted to go abroad with my wife with the right to return as soon as it becomes possible in our country to serve great ideas in literature without cringing before little men".

It appeared only a matter of time before Zamyatin would be arrested and imprisoned. However, in 1931 Maxim Gorky managed to use his influence over Joseph Stalin to allow Zamyatin to leave the Soviet Union.

Zamyatin settled in France where he wrote screenplays such as Anna Karenina. He also wrote an unfinished novel, The Scourge of God, a satire on the Russian Revolution. Yevgeni Zamyatin died of a heart attack in Paris on 10th March, 1937.

We, although never published in the Soviet Union, deeply influenced other novels about the future such as Brave New World by Aldous Huxley and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell.

Primary Sources

(1) Yevgeni Zamyatin, Tomorrow (1919)

Every today is at the same time a cradle and a shroud: a shroud for yesterday, a cradle for tomorrow. Today is doomed to die - because yesterday died, and because tomorrow will be born. Such is the wise and cruel law. Cruel, because it condemns to eternal dissatisfaction those who already today see the distant peaks of tomorrow; wise, because eternal dissatisfaction is the only pledge of eternal movement forward, eternal creation. He who has found his ideal today is, like Lot's wife, already turned to a pillar of salt, has already sunk into the earth and does not move ahead. The world is kept alive only by heretics: the heretic Christ, the heretic Copernicus, the heretic Tolstoy. Our symbol of faith is heresy: tomorrow is an inevitable heresy of today, which has turned into a pillar of salt, and to yesterday, which has scattered to dust. Today negates yesterday, but tomorrow is a negation of negation. Thesis yesterday, antithesis today, and synthesis tomorrow.

(2) Yevgeni Zamyatin, I Am Afraid (1921)

I am afraid that we preserve too fondly too much of what we have inherited from the palaces. Take these gilded chairs-yes, surely, they must be preserved: they are so graceful, they embrace so tenderly any rear end deposited in them. And it may, perhaps, be true that court poets resemble the exquisite gilded chairs in their grace and tenderness. But is it not a mistake to preserve the institution of court poets with as much solicitude as we preserve the gilded chairs? After all, only the palaces remain; the court is no longer here.

I am afraid that we are too kind, and that the French Revolution was more ruthless in destroying everything connected with the court. On the eleventh day of Messidor, in 1794, Payan, chairman of the Commission on Public Education, issued a decree, which stated, among other things:

We have a multitude of nimble authors, who keep a constant eye on the latest trend; they know the fashion and color of the given season; they know when it is time to don the red cap, and when to discard it … As a result, they merely corrupt and degrade art. True genius creates thoughtfully and embodies its ideas in bronze, but mediocrity, hiding under the aegis of freedom, snatches a fleeting triumph in its name and plucks the flowers of ephemeral success.

With this contemptuous decree, the French Revolution guillotined the masquerading court poets. But we offer the writings of these "nimble authors, who know when to don the red cap, and when to discard it," when to sing hail to the tsar, and when to the hammer and sickle-we offer them to the people as a literature worthy of the revolution. And the literary centaurs rush, kicking and crushing one another, in a race for the splendid prize -the monopoly on the scribbling of odes, the monopoly on the knightly pursuit of slinging mud at the intelligentsia. I am afraid Payan was right-this merely corrupts and degrades art. And I am afraid that, if this continues, the entire recent period in Russian literature will become known in history as the age of the nimble school, for those who are not nimble have been silent now for the past two years.

And what was contributed to literature by those who were not silent?

The nimblest of all were the Futurists. Without a moment's pause, they proclaimed themselves the court school. And for a year we heard nothing but their yellow, green, and raspberry red triumphant cries. However, the combination of the red sans-culotte cap with the yellow blouse and yesterday's still visible blue flower on the cheek proved too blasphemously glaring even for the least demanding. The Futurists were politely shown the door by those in whose name these self-appointed heralds galloped. Futurism disappeared. And as before, a single beacon rises amid the tin-flat Futurist sea-Maiakovskii. Because he is not one of the nimble. He sang the revolution when others, sitting in Petersburg, were firing their long-range verses at Berlin. But even this magnificent beacon is still burning with the old reserves of his "I" and "Simple as Lowing." In the "Heroes and Victims of the Revolution," in "Doughnuts" and the poem about the peasant woman and Vrangel, it is no longer the same Maiakovskii, the Edison, the pioneer whose every step was hacked out in the jungle. From the jungle he has come out upon the well-trodden highway; he has dedicated himself to perfecting official themes and rhythms. But, then, why not? Edison, too, perfected Bell's invention.

The "horsism" of the Moscow Imaginists is too obviously weighed down by the cast-iron shadow of Maiakovskii. No matter how they exert themselves to smell bad and to shout, they will not outsmell and outshout Maiakovskii. The Imaginist America, alas, has been discovered long before. Back in the era of Serafino, one who considered himself the greatest of poets wrote: "Were I not fearful of disturbing the air of your modesty with a golden cloud of honors, I could not have refrained from decking the windows of the edifice of fame with the bright vestments with which the hands of praise adorn the backs of names that are the portion of superior beings" (Letter from Pietro Aretino to the Duchess of Urbino). "The hands of praise," "the backs of names"-isn't this Imaginism? An excellent and pungent means-the image-has become an end in itself; the cart pulls the horse.

The proletarian writers and poets are diligently trying to be aviators astride a locomotive. The locomotive huffs and puffs sincerely and assiduously, but it does not look as if it can rise aloft. With small exceptions (such as Mikhail Volkov of the Moscow "Smithy"), all the practitioners of proletarian culture have the most revolutionary content and the most reactionary form. The Proletkult art is, thus far, a step back, to the 1860s. And I am afraid that the airplanes from among the nimble will always outstrip the honest locomotives and, "hiding under the aegis of freedom," will snatch a fleeting triumph in its name.

Fortunately, the masses have a keener nose than they are given credit for. And therefore, the triumph of the nimble is only momentary. Thus, the fleeting triumph of the Futurists, and the equally fleeting triumph of Kliuev, after his patriotic verses about the base Wilhelm and his enthusiasm over the "rebuff in decrees" and the machine gun (a ravishing rhyme: machine-gunning and honey!). And even this brief measure of success was apparently denied to Gorodetskii: at the evening in the Duma hall he had a cool reception, and his own evening at the House of the Arts was attended by fewer than ten people.

And the non-nimble are silent. Blok's "Twelve" struck two years ago-and after the last, twelfth stroke, Blok fell silent. Barely noticed, the "Scythians" rushed, long ago, down the dark, trolleyless streets. Last year's Notes of Dreamers [a series of anthologies of the Symbolist group, published by the Alkonost publishing house in 1919-22], published by Alkonost are but a dim, solitary glimmer in the dark yesterday. And in them, we hear Andrei Belyi complaining:

The conditions under which we live are tearing us to pieces. The writer often collapses under the burden of work that is alien to him. For months, he has no opportunity to concentrate and finish an uncompleted phrase. Frequently of late the author has asked himself whether anyone needs him-that is, whether anyone needs Petersburg or The Silver Dove. Perhaps he is needed only as a teacher of "poetic science"? If so, he would immediately put down his pen and try to find a job as a street cleaner, rather than violate his soul by surrogates of literary activity.

Yes, this is one of the reasons for the silence of true literature. The writer who cannot be nimble must trudge to an office with a briefcase if he wants to stay alive. In our day, Gogol would be running with a briefcase to the Theater Section; Turgenev would undoubtedly be translating Balzac and Flaubert for World Literature; Herzen would lecture to the sailors of the Baltic fleet; and Chekhov would be working for the Commissariat of Public Health. Otherwise-to live as a student did five years ago on his forty rubles-Gogol would have to write four Inspector Generals a month, Turgenev would have to turn out three Fathers and Sons every two months, and Chekhov would have to produce a hundred stories every month. This sounds like a preposterous joke, but unfortunately it is not a joke; these are realistic figures. The work of a literary artist, who "embodies his ideas in bronze" with pain and joy, and the work of a prolific windbag – the work of Chekhov and that of Breshko-Breshkovskii – are today appraised in the same way: by the yard, by the sheet. And the writer faces the choice: either he becomes a Breshko-Breshkovskii or he is silent. To the genuine writer or poet the choice is clear.

But even this is not the main thing. Russian writers are accustomed to going hungry. The main reason for their silence is not lack of bread or lack of paper; the reason is far weightier, far tougher, far more ironclad. It is that true literature can exist only where it is created, not by diligent and trustworthy officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels and skeptics. But when a writer must be sensible and rigidly orthodox, when he must make himself useful today, when he cannot lash out at everyone, like Swift, or smile at everything, like Anatole France, there can be no bronze literature, there can be only a paper literature, a newspaper literature, which is read today, and used for wrapping soap tomorrow.

Those who are trying to build a new culture in our extraordinary time often turn their eyes to the distant past-to the stadium, the theater, the games of the Athenian demos. The retrospection is correct. But it must not be forgotten that the Athenian agora, the Athenian people, knew how to listen to more than odes; it had no fear of the harsh scourge of Aristophanes either. And we-how far we are from Aristophanes when even the utterly innocuous Toiler of Wordstreams by Gorky is withdrawn from the repertory to shield that foolish infant, the Russian demos, from temptation!

I am afraid that we shall have no genuine literature until we cease to regard the Russian demos as a child whose innocence must be protected. I am afraid that we shall have no genuine literature until we cure ourselves of this new brand of Catholicism, which is as fearful as the old of every heretical word. And if this sickness is incurable, then I am afraid that the only future possible to Russian literature is its past.

(3) Yevgeni Zamyatin, The Day and Age (1924)

In America there is a society for the suppression of vice which once decided, in order to prevent temptation, that all the naked statues in a New York museum must be dressed in little skirts like those of ballet dancers. These puritan skirts are merely ridiculous, and do little damage; if they have not yet been removed, a new generation will remove them and see the statues as they are. But when a writer dresses his novel in such a skirt, it is no longer laughable. And when this is done not by one, but by dozens of writers, it becomes a menace. These skirts cannot be removed, and future generations will have to learn about our epoch from tinseled, straw-filled dummies. They will receive far fewer literary documents than they might have. And it is therefore all the more important to point out such documents where they exist.

(4) Alexander Efremin attacked the writing of Yevgeni Zamyatin in his article The Fatal Path (4th January, 1930)

Zamyatin has a complete and unmitigated disbelief in the Revolution, a thorough and persistent skepticism, a departure from reality, an extreme individualism, a clearly hostile attitude to the Marxist-Leninist world view, the justification of any "heresy", of any protest in the name of that protest, a hostile attitude to the factors of class war - this is the complex of ideas within which Zamyatin revolves. Thrown out beyond the bounds of the Revolution by its centrifugal force, he, of necessity, is in the enemy camp, in the ranks of the bourgeoisie.

(5) Yevgeni Zamyatin, How We Write (1931)

I spend much time in rewriting, evidently much more than is necessary for the reader. But this is necessary for the critic, the most demanding and most caviling critic that I know of; for myself. I am never successful in deceiving this critic, and until he tells me that everything that is possible has been done.

If I consider anybody else's opinion, then it is only the opinion of my friends, of whom I know that they know how a novel, a story, a play is made: they themselves have made them - and made them really well. For me, there is no other criticism, and how it could exist, is incomprehensible to me.

(6) Yevgeni Zamyatin, letter to Joseph Stalin (June, 1931)

No creative activity is possible in an atmosphere of systematic persecution that increases in intensity from year to year. In each of my published works these critics have inevitably discovered some diabolical intent. Regardless of the content of a given work, the very fact of my signature has become a sufficient reason for declaring the work criminal. Of course, any falsification is permissible in fighting the devil.

I beg to be permitted to go abroad with my wife with the right to return as soon as it becomes possible in our country to serve great ideas in literature without cringing before little men, as soon as there is at least partial change in the prevailing view concerning the role of the literary artist.

I do not wish to conceal that the fundamental reason for my request for permission to go abroad together with my wife is my hopeless situation here as a writer, the death sentence which has been passed on me here as a writer.

(7) Marc Slonim met Yevgeni Zamyatin in Paris shortly before his death.

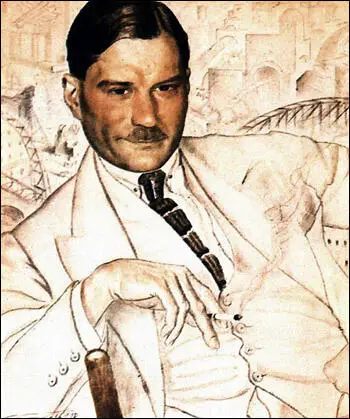

He was lean, of medium height, clean shaven, with reddish-blond hair parted on the side. Then in his early fifties, he looked much younger, and the malicious twinkle in his grey eyes gave a boyish expression to his handsome face. Always wearing tweeds and with an unextinguished pipe in his wide, generous mouth, he resembled an Englishman.

(8) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

When the Press denounced Zamyatin and Pilniak as public enemies, the first for a biting satire on totalitarianism, the other for a fine realist novel, my author friends (in the Soviet Writers' Union) voted everything that was expected of them against their two comrades.