Public Health

One of the things that Romans noticed as they travelled the world was that people from different areas suffered from different diseases. For example, they discovered that people living near marshes and swamps often suffered from a disease we now call malaria.

From evidence such as this, the Romans, like the Greeks before them, became convinced that the physical environment was one of the main causes of disease. The Romans were therefore very careful where they built new towns. Before a decision was taken, animals that had been grazing in the area were killed. Their livers were inspected and if they were a greenish-yellow, the area was rejected as being too unhealthy.

The Romans suspected that the quality of the water people drank was an important factor in obtaining good health. For hundreds of years the Romans had used the River Tiber for washing, drinking and for dumping their waste. The Roman government decided that an attempt should be made to separate the water used for these different purposes.

In 312 BC work was started on the first Roman aqueduct. Within a hundred years, nine aqueducts were

supplying the Roman people with water from nearby mountain lakes. At certain points along the pipes, the water entered settling basins which filtered the sediment from the water.

When the water arrived in Rome it went into several large reservoirs. The best quality water went to the city's drinking fountains while the most polluted was used to water plants and flowers.

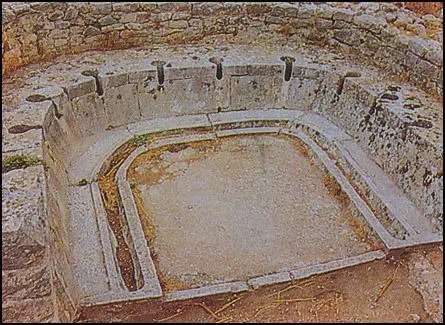

The Roman government also attempted to deal with the problem of sewage disposal. Public toilets were built all over Rome. They were connected to a system of underground drains that took the sewage from the toilets to the River Tiber.

Rich people in Rome were able to pay to have fresh water piped into their houses. They also had toilets installed that were connected to the underground sewage system. However, the vast majority of people in Rome had to walk to their nearest fountain or public toilet. Some people could not be bothered and, when it was more convenient, still obtained their water from the River Tiber.

Although Roman attempts to improve the health of the public were fairly successful, outbreaks of different diseases still took place fairly often.

Rome had a considerable number of doctors to treat people when they were ill. However, this treatment had to be paid for and many Romans could not afford it.

The government became concerned about the large numbers of people who died while they were still young.

Outbreaks of disease often led to serious labour shortages. It was therefore decided that medical treatment should be provided free of charge to those too poor to pay. By the 2nd century AD every city and town was expected to employ doctors to treat the poor when they were sick. These doctors also had

the responsibility of training future doctors.

The Romans were not the first people to realise that it was a good idea for the government to take responsibility for the health of its people. For example, cities in India had a good sewage system 2,000 years before the Romans. However, the Romans were more aware of the importance of public health than any other previous civilisation. Also, the Romans controlled a large empire. This meant that aqueducts, fountains, reservoirs, public toilets and sewage pipes were not only built in Rome but all over the world.

Primary Sources

(1) Juvenal, Satire III (c. AD 100)

Those cracked or leaky pots that people toss out through windows. Look at the way they smash, the weight of them, the damage they do to the pavement!... You are a fool if you don't make your will before venturing out to dinner... Along your route at night may prove a death-trap: so pray and hope (poor you!) that the local housewives drop nothing worse on your head than a pailful of slops.

(2) Roman Law (c. AD 150)

If the apartment is divided among several tenants, redress can be sought only against the one who lives in the part of the apartment from which the liquid was poured... When in consequence of the fall of one of these projectiles... the body of a free man shall have suffered injury, the judge shall award to the victim in addition to medical fees and other expenses incurred in his treatment, the total of the wages of which he has been or shall in future be deprived by the inability to work.

(3) Frontinus, Aqueducts (c. AD 80)

The improved health of Rome is a result of the greater number of reservoirs, aqueducts, fountains, and water basins... the appearance of Rome is cleaner and changed, and the causes of the unhealthy atmosphere, that gave Rome so bad a name among the ancients, are now removed.

(4) Vitruvius, On Architecture (c. AD 10)

When you build a town you need to choose a healthy site... A marshy area must be avoided. For when the morning breezes come... they bring the poisoned breaths of marsh animals... I agree with the old method. For the ancients sacrificed the beasts which were feeding in those places where towns were being placed, and then inspected their livers... If they found them faulty, they judged that the supply of food and water which was to be found in these places would be harmful.

(5) Columella, On Agriculture (c. AD 50)

You should avoid marshy areas... A marsh always sends out harmful poisonous vapours during the hot periods of the summer, and, at this time, gives birth to animals possessing mischief-making stings... thus unknown diseases are often contracted.

(6) Varro, Antiquitates (c. 35 BC)

Precautions must be taken in the neighbourhood of swamps... because there are certain very small creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases.

1. What evidence is there in these sources that there was a long period of time when little was done about improving the unhealthy condition of Rome?

2. Describe the different ways that the Roman government attempted to improve the health of the Roman people.

3 Read source 2. Select another source from this unit that hetps to explain why the law mentioned in 2 was passed.

4. Comment on the value of the sources in this unit for a historian writing a book about the Roman government's attempts to improve the health of the Roman people.