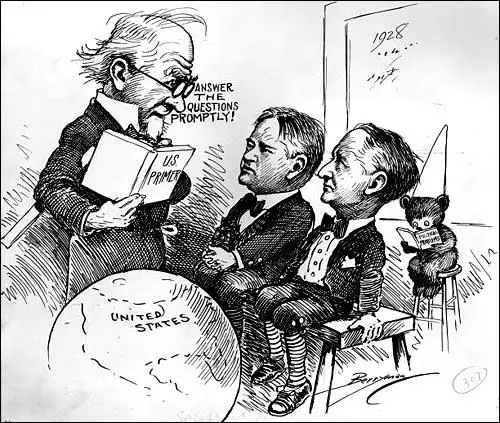

1928 Presidential Election

President Calvin Coolidge announced in August 1927 that he would not seek a second full term of office. Coolidge was unwilling to nominate Herbert Hoover as his successor. The two men had a poor relationship on one occasion he remarked that "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice - all of it bad. I was particularly offended by his comment to 'shit or get off the pot'." (1)

Coolidge was not alone in thinking that Hoover might be a bad candidate. Republican leaders cast about for an alternative candidate such as Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and the former Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, Despite these reservations, Hoover won the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the convention. Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas was selected as his running-mate. One newspaper reported: "Hoover brings character and promise to the Republican ticket. He is a new kind of candidate in a day surfeited with old forms and old habits in politics." (2)

Senator George H. Moses, chairman of the Republican national convention, sent a letter congratulating Hoover on his nomination. He replied: "You convey too great a compliment when you say that I have earned the right to the presidential nomination. No man can establish such an obligation upon any part of the American people. My country owes me no debt. It gave me, as it gives every boy and girl, a chance. It gave me schooling, independence of action, opportunity for service and honor. In no other land could a boy from a country village, without inheritance or influential friends, look forward with unbounded hope. My whole life has taught me what America means. I am indebted to my country beyond any human power to repay." (3)

One of the main issues in the election campaign was the taxes imposed on imports. The Fordney-McCumber Act of 1922 raised American tariffs on many imported goods to protect factories and farms. The tariff rate was an average of about 38.5% for dutiable imports and an average of 14% overall. However, in response to this, most of American trading partners had raised their own tariffs to counter-act this measure. (4)

Industrialists such as Henry Ford attacked the tariff and argued that the American automobile industry did not need protection since it dominated the domestic market and its main objective was to expand foreign sales. He pointed out that France raised its tariffs on automobiles from 45% to 100% in response to the Fordney-McCumber Act. Ford and other industrialists tended to favour the idea of free trade. (5)

David Walsh, a member of the Democratic Party, challenged the tariff by arguing that the farmers were net exporters and so did not need protection; they depended on foreign markets to sell their surplus. Hoover and the Republicans still believed in tariffs. William Borah, the charismatic senator from Idaho, widely regarded as a true champion of the American farmer, had a meeting with Hoover and offered to give him his full support if he promised to increase tariffs of agricultural products if elected. (6) Nearly a quarter of the American labour force was then employed on the land and Hoover wanted their vote. He therefore agreed with the proposal and during the campaign promised the American electorate that he would revise the tariff. (7)

The Democratic candidate was Al Smith. As governor of New York he attempted to bring an end to child labour, improve factory laws, housing and the care of the mentally ill. During his campaign Smith gave his support for an increase to the tariffs for imported goods, even though most of the party leaders, including Cordell Hull, John J. Raskob, Burton K. Wheeler and Harry F. Byrd, were strong opponents of the Fordney-McCumber Act. (8)

Smith was the first Roman Catholic to be a serious candidate for the presidency. This became a serious problem in the Deep South and the Ku Klux Klan burned Smith's effigy and Catholics were vilified for letting blacks worship in the same churches as whites. In the 1928 Presidential Election several states that had previously voted Democrat, such as Texas, Florida, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia voted Republican. Smith won 40.8% of the vote compared to Hoover's 58.2%. (9)

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday (1931)

A few weeks after the somewhat unenthusiastic nomination of Herbert Hoover by the Republicans, that coalition of incompatibles known as the Democratic party nominated Governor Alfred E. Smith of New York, a genial son of the East Side with a genius for governmental administration and a taste for brown derbies. Al Smith was a remarkable choice. His Tammany affiliations, his wetness, and above all the fact that he was a Roman Catholic made him repugnant to the South and to most of the West. Although the Ku Klux Klan had recently announced . the abandonment of its masks and the change of its name to "Knights of the Great Forest," anti-Catholic feeling could still take ugly forms. That the Democrats took the plunge and nominated Smith on the first ballot was eloquent testimony to the vitality of his personality, to the widespread respect for his ability, to the strength of the belief that any Democrat could carry the Solid South and that a wet candidate of immigrant stock would pull votes from the Republicans in the industrial North and the cities generally, and to the lack of other available candidates.

(2) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

That presidential election with Governor Smith, a Jeffersonian Democratic politician, running to defeat against Hoover, an engineer in business, seemed to mark the end of a period, my period, and perhaps of a culture, the moral culture. Hoover was the Hamiltonian, who had no democracy in him, none, neither political nor economic. He has shown no sense of the perception that privileges are a cause of our social trouble. He is a moralist in that. He believes in the ownership and management by business men of all business, including land and natural resources, transportation, power, light. Good business is all the good we need. Politics was the only evil, and he has no sense of politics. When he came home from his years and years of professional service in foreign lands, he did not know or care whether he was a Democrat or a Republican; he was a candidate and won some votes for the nomination for president at a Democratic convention. He stood four years later as the Republican candidate of and for business against an able, successful Democrat who was a philosophic, political democrat. And the people believed, as they voted, with Hoover. Food, shelter, and clothing, plus the car, the radio-prosperity interested them more than any old American principles, which were all on the Democratic side with Smith. I went through that campaign, sensitive, interested, non-partisan. What little I said was in the Jeffersonian tradition, but I was watching to report, not playing to win. I can assert that everybody was for business; even the Democrats who voted for Smith, were for good business, of course; they, too, expected Smith to carry on the good times and favor business. It seems to me that there are many more Republicans in this country than voted for Hoover, that our southern Democrats, party-bound by their traditions, are unconscious Republicans who only think that they are Democrats, who don't know that they are Republicans. In California, where I was living, there were no politics or principles at all. It was all business. In brief, that was an economic election which sent to the White House Herbert Hoover to do what he is trying to do: to represent business openly, as Coolidge and other presidents had covertly.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject