Olga Kameneva

Olga Davidovna Kameneva was born in Yanovka, Russia, on 7th November, 1883. Her older brother was Leon Trotsky. Her parents were Jewish and owned a farm in the Ukraine. Trotsky later recalled: "My father and mother lived out their hard-working lives with some friction, but very happily on the whole. Of the eight children born of this marriage, four survived. I was the fifth in order of birth. Four died in infancy, of diphtheria and of scarlet fever, deaths almost as unnoticed as was the life of those who survived. The land, the cattle, the poultry, the mill, took all my parents' time; there was none left for us. We lived in a little mud house. The straw roof harboured countless sparrows' nests under the eaves. The walls on the outside were seamed with deep cracks which were a breeding place for adders. The low ceilings leaked during a heavy rain, especially in the hall, and pots and basins would be placed on the dirt floor to catch the water. The rooms were small, the windows dim; the floors in the two rooms and the nursery were of clay and bred fleas."

Trotsky was very close to his younger sister: "We usually sat in the dining-room in the evening until we fell asleep.... Sometimes a chance word of one of the elders would waken some special reminiscence in us. Then I would wink at my little sister, she would give a low giggle, and the grown-ups would look absent-mindedly at her. I would wink again, and she would try to stifle her laughter under the oilcloth and would hit her head against the table. This would infect me and sometimes my older sister too, who, with thirteen-year-old dignity, vacillated between the grown-ups and the children. If our laughter became too uncontrollable, I was obliged to slip under the table and crawl among the feet of the grown-ups, and, stepping on the cat's tail, rush out into the next room, which was the nursery. Once back in the dining-room, it all would begin over again. My fingers would grow so weak from laughing that I could not hold a glass. My head, my lips, my hands, my feet, every inch of me would be shaking with laughter."

Leon Trotsky became involved in left-wing politics and was eventually arrested and sent to Siberia. After four years in captivity, he escaped and eventually made his way to London. Trotsky joined the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) and while in England he met and worked with a group of Marxists producing the journal Iskra. This included George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, Lenin and Julius Martov. Olga, aged 19, also joined the SDLP. Soon afterwards she married another member, Lev Kamenev.

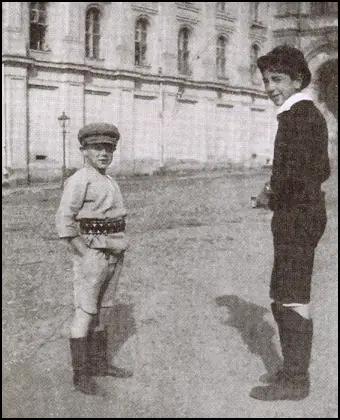

In February 1902 Kamenev took part in student demonstrations against Nicholas II. The following month he was arrested at another demonstration and was imprisoned in Butyrki. He was released a few months later but was not allowed to continue his university studies. The couple moved to Paris where they met Lenin and his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya. Together they moved to Geneva in Switzerland. Olga Kameneva gave birth to a son, Alexander, in 1906.

Kamenev soon emerged as one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Labour Party in exile. At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Party in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Julius Martov, two of the party's main leaders. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Martov won the vote 28-23 but Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks. Olga joined the Bolsheviks but her brother, Leon Trotsky, became a member of the Mensheviks.

On 3rd April, 1917, Lenin announced what became known as the April Theses. Lenin attacked Bolsheviks for supporting the Provisional Government. Instead, he argued, revolutionaries should be telling the people of Russia that they should take over the control of the country. In his speech, Lenin urged the peasants to take the land from the rich landlords and the industrial workers to seize the factories.

Lev Kamenev led the opposition to Lenin's call for the overthrow of the government. In Pravda he disputed Lenin's assumption that "the bourgeois democratic revolution has ended," and warned against utopianism that would transform the "party of the revolutionary masses of the proletariat" into "a group of communist propagandists." A meeting of the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee the day after the April Theses appeared voted 13 to 2 to reject Lenin's position.

In September 1917, Lenin sent a message to the Bolshevik Central Committee via Ivar Smilga. "Without losing a single moment, organize the staff of the insurrectionary detachments; designate the forces; move the loyal regiments to the most important points; surround the Alexandrinsky Theater (i.e., the Democratic Conference); occupy the Peter-Paul fortress; arrest the general staff and the government; move against the military cadets, the Savage Division, etc., such detachments as will die rather than allow the enemy to move to the center of the city; we must mobilize the armed workers, call them to a last desperate battle, occupy at once the telegraph and telephone stations, place our staff of the uprising at the central telephone station, connect it by wire with all the factories, the regiments, the points of armed fighting, etc." Lev Kamenev proposed replying to Lenin with an outright refusal to consider insurrection, but this step was turned down. Eventually it was decided to postpone any decision on the matter.

Leon Trotsky was the main figure to argue for an insurrection whereas Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Victor Nogin led the resistance to the idea. They argued that an early action was likely to result in the Bolsheviks being destroyed as a political force. As Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) has explained why Zinoviev felt strongly about the need to wait: "The experience of the summer (the July Days) had brought him to the conclusion that any attempt at an uprising would end as disastrously as the Paris Commune of 1871; revolution was was inevitable, he wrote at the time of the Kornilov crisis, but the party's task for the time being was to restrain the masses from rising to the provocations of the bourgeoisie."

At a meeting of the Central Committee on 9th October, Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev were the only members opposed to Lenin's call for revolution. He later changed his mind and took part in the October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power.

After the Russian Revolution Kameneva was put in charge of the Theater Division (TEO) of the People's Commissariat for Education. She served under Anatoli Lunacharsky and worked closely with Vsevolod Meyerhold in an attempt to radicalize the theatre in Soviet Russia. This policy changed in 1919 and Lunacharsky sacked Kameneva. However, she still kept her job as a member of the board of directors of the Soviet Communist Party's Women's Section. Ethel Snowden, who met her during this period described her her as "an amiable little lady".

In the summer of 1920 Lev Kamenev was sent as head of a Soviet Trade Delegation to London. On 14th August, Kamenev met the British artist, Clare Sheridan. He agreed to sit for her and Sheridan recorded in her autobiography, Russian Portraits (1921): "There is very little modelling in his face, it is a perfect oval, and his nose is straight with the line of his forehead, but turns up slightly at the end, which is a pity. It is difficult to make him look serious, as he smiles all the time Even when his mouth is severe his eyes laugh.... We had wonderful conversations. He told me all kinds of details of the Soviet legislation, their ideals and aims. Their first care, he told me, is for the children, they are the future citizens and require every protection. If parents are too poor to bring up their children, the State will clothe, feed, harbour and educate them until fourteen years old, legitimate and illegitimate alike, and they do not need to be lost to their parents, who can see them whenever they wish. This system, he said, had doubled the percentage of marriages (civil of course), and it had also allayed a good deal of crime - for what crimes are not committed to destroy illegitimate children?

Clare Sheridan took a holiday with Kamenev on the Isle of Wight. While they were there Kamenev promised her that he would arrange for her to return to Moscow with him. She told her cousin, Shane Leslie, that doing busts of Lenin and Leon Trotsky might bring her world fame. On 5th September 1920, Clare's brother, Oswald Frewen, wrote in his diary: "Puss (Clare) is trying to go to Moscow with Kamenev to sculpt Lenin and Leon Trotsky.... I rather she didn't go but she has got Bolshevism badly - she always reflects the views of the last man she's met - and I think it may cure her to go and see it. She is her own mistress and if I thwarted her by telling Winston, she'd never confide in me again.... I went to the Bolshevik Legation in Bond Street with her and waited while she saw Kamenev. Several typical Bolshies there - degenerate lot."

Sheridan and Kamenev arrived in Moscow on 20th September, 1920. Olga Kameneva was on the station to greet him. Sheridan wrote in her book, Russian Portraits (1921): "We reached Moscow at 10.30 a.m. and I waited in the train so that Kamenev and his wife could get their tender greetings over without my presence. I watched them through the window: the greeting on one side, however, was not apparent in its tenderness. I waited and they walked up the platform talking with animation. Finally Mrs. Kameneva came into the compartment and shook hands with me. She has small brown eyes and thin lips."

During the Russian Civil War Olga Kameneva was a leading member of the Central Commission for Fighting the After-Effects of the Famine. In 1923 she was appointed head of the Commission for Foreign Relief (KZP). She also served as chairman of the USSR Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (1926-28). Lev Kamenev left her for Tatiana Glebova, with whom he had a son, Vladimir Glebov.

During this period Kamenev and her brother, Leon Trotsky were involved in a struggle for power with Joseph Stalin. In the spring of 1927 Trotsky drew up a proposed programme signed by 83 oppositionists. He demanded a more revolutionary foreign policy as well as more rapid industrial growth. He also insisted that a comprehensive campaign of democratisation needed to be undertaken not only in the party but also in the soviets. Trotsky added that the Politburo was ruining everything Lenin had stood for and unless these measures were taken, the original goals of the October Revolution would not be achievable.

According to Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996): "The opposition then organized demonstrations in Moscow and Leningrad on November 7. These were the last two open demonstrations against the Stalinist regime. The GPU, of course, knew about them in advance but allowed them to take place. In Lenin's Party submitting Party differences to the judgment of the crowd was considered the greatest of crimes. The opposition had signed their own sentence. And Stalin, of course, a brilliant organizer of demonstrations himself, was well prepared. On the morning of November 7 a small crowd, most of them students, moved toward Red Square, carrying banners with opposition slogans: Let us direct our fire to the right - at the kulak and the NEP man, Long live the leaders of the World Revolution, Trotsky and Zinoviev.... The procession reached Okhotny Ryad, not far from the Kremlin. Here the criminal appeal to the non-Party masses was to be made, from the balcony of the former Paris hotel. Stalin let them get on with it. Smilga and Preobrazhensky, both members of Lenin's Central Committee, draped a streamer with the slogan Back to Lenin over the balcony."

However, as Robert V. Daniels has argued: "After vainly challenging the party organization in a wide-ranging controversy over the future of the proletarian dictatorship, the opposition leaders were ousted from all their party posts." Stalin argued that there was a danger that the party would split into two opposing factions. If this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union. On 14th November 1927, the Central Committee decided to expel Leon Trotsky and Gregory Zinoviev from the party. This decision was ratified by the Fifteenth Party Congress in December. The Congress also announced the removal of another 75 oppositionists, including Lev Kamenev, Yuri Piatakov, Mikhail Lashevich, Karl Radek, Ivar Smilga, Ivan Smirnov and Christian Rakovsky.

Sergey Kirov was assassinated by a young party member, Leonid Nikolayev, on 1st December, 1934. Stalin claimed that Nikolayev was part of a larger conspiracy led by Leon Trotsky against the Soviet government. This resulted in the arrest and trial in August, 1936, of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin. Yuri Piatakov, the former critic of Stalin, accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

Sidney Webb, who was a visitor to the Soviet Union in 1932, argued in 1935: "In December 1934 the head Bolshevik official in Leningrad (Kirov) was assassinated by a dismissed employee, who may have acted independently out of personal revenge, but who was discovered to have secret connections with conspiratorial circles of ever-widening range. The Government reaction to this murder was to hurry on the trial, condemnation, and summary execution of the hundred or more persons above referred to, who were undoubtedly guilty of illegal entry and inexcusably bearing arms and bombs, although it was apparently not proved that they had any connection with Kirov's assassination or the conspiracies associated therewith."

At the first of what became known as show trials, the men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

Most journalists covering the trial were convinced that the confessions were statements of truth. The Observer reported: "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine." The The New Statesman commented: "Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation."

Kamenev's final words in the trial concerned the plight of his children: "I should like to say a few words to my children. I have two children, one is an army pilot, the other a Young Pioneer. Whatever my sentence may be, I consider it just... Together with the people, follow where Stalin leads." Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), later explained that the reason he made this false confession was that he had been promised that the lives of his two sons would be spared. Lev Kamenev was found guilty and executed in Moscow on 25th August, 1936.

Olga Kameneva was also arrested and imprisoned. Her younger son, Yuri Lvovich Kamenev, was executed on 30th January 1938 at the age of 17. Her older son, Air Force officer Alexander Lvovich Kamenev, was executed on 15th July 1939. Kameneva was shot on 11th September 1941 along with Christian Rakovsky, Maria Spiridonova and 160 other prominent political prisoners by the NKVD in the Medvedev Forest.

Primary Sources

(1) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930)

We usually sat in the dining-room in the evening until we fell asleep. People came and went in the dining-room, taking or returning keys, making arrangements of various kinds, and planning the work for the following day. My younger sister 0lga, my older sister Liza, the chambermaid and myself then lived a life of our own, which was dependent on the life of the grown-ups, and subdued by theirs. Sometimes a chance word of one of the elders would waken some special reminiscence in us.

Then I would wink at my little sister, she would give a low giggle, and the grown-ups would look absent-mindedly at her. I would wink again, and she would try to stifle her laughter under the oilcloth and would hit her head against the table. This would infect me and sometimes my older sister too, who, with thirteen-year-old dignity, vacillated between the grown-ups and the children. If our laughter became too uncontrollable, I was obliged to slip under the table and crawl among the feet of the grown-ups, and, stepping on the cat's tail, rush out into the next room, which was the nursery. Once back in the dining-room, it all would begin over again. My fingers would grow so weak from laughing that I could not hold a glass. My head, my lips, my hands, my feet, every inch of me would be shaking with laughter.

"Whatever is the matter with you?" my mother would ask. The two circles of life, the upper and the lower, would touch for a moment. The grown-ups would look at the children with a question in their eyes that was sometimes friendly but more often full of irritation. Then our laughter, taken unawares, would break out tempestuously into the open. Olga's head would go under the table again, I would throw myself on the sofa, Liza would bite her upper lip, and the chambermaid would slip out of the door.

(2) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

20th September, 1920: Yesterday evening after we had started, Kamenev left us to go and talk to Zinoviev who was on the Petrograd train, travelling also to Moscow. Zinoviev is President of the Petrograd Soviet (and also of the Third International). I did not see Kamenev again that evening, but at 2 a.m. he knocked at my door and awakened me with many apologies to tell me news he thought I should like to hear. Zinoviev had just told him that the telegram announcing his arrival with me came in the middle of a Soviet Conference. It caused a good deal of amusement, but Lenin said that whatever one felt about it there was nothing to do but to give me some sittings as I had come so far for the purpose. "So Lenin has consented and I thought it was worth while to wake you up to tell you that." Kamenev was in great spirits; Zinoviev had evidently told him things he was glad to hear, especially, I gathered, that no blame or censure was going to be put upon him for having failed in his mission to England.

We reached Moscow at 10.30 a.m. and I waited in the train so that Kamenev and his wife could get their tender greetings over without my presence. I watched them through the window: the greeting on one side, however, was not apparent in its tenderness. I waited and they walked up the platform talking with animation. Finally Mrs. Kamenev came into the compartment and shook hands with me. Mrs. Philip Snowden in her book has described her as "an amiable little lady".

She has small brown eyes and thin lips. She looked at the remains of our breakfast on the saloon table and said

querulously, "We don't live chic like that in Moscow." Goodness, I thought, not even like that! There was more

discussion in Russian between the two, and my expressionless face watched them. I have become reconciled to not being unable to understand.As we left the train she said to me: "Leo Kamenev has quite forgotten about Russia, the people here will say he is a bourgeois." Leo Kamenev spat upon the platform in the most plebeian way, I suppose to disprove this. It was extremely unlike him.

We piled into a beautiful open Rolls-Royce car and were driven at full speed with a great deal of hooting through streets that were shuttered as after an air raid. Mrs. Kamenev said to me: "It is dirty, our Moscow, isn't it?" Well, yes, one could not very well say that it was not.

We came to the Kremlin. It is high up and dominates Moscow and consists of the main palace, some other palaces, convents, monasteries, and churches encircled by a wall and towers. The sun was shining when we arrived and all the gold domes were glittering in the light. Everywhere one looked there were domes and towers.

We drove up to a side entrance under an archway, and then made our way, a solemn procession, carrying luggage up endless stone stairs and along stone corridors to the Kamenev apartments. A little peasant maid with a yellow handkerchief tied over her head ran out to greet us, and kissed Kamenev on the mouth. Then ensued the awkward moment of being shown to no room. After eleven days travelling one felt a longing for peace, and to be able to unpack, instead of which the Russian discussion was resumed, and I sat stupidly still with nothing to say.