January's Written Primary Source for the History Classroom

Activities for the History Classroom

31st January, 2022: Ada Nield Chew, The Crewe Chronicle (19th May, 1894)

In your issue of 5 May you were good enough to publish a letter of mine on the above subject, and also to invite me to write you further on our wages, hours of work, and conditions of employment. Before responding to the same I have waited in the hope that an abler pen than mine might take up my subject and say a word on our behalf. I conclude, however, that sufficient interest is not taken in factory girls and their wrongs outside their own sphere to call for any comment. Speaking for ourselves, sir, I can assure you that this question of prices paid for our work and the general inadequacy of the same in proportion to the work done is one naturally of keen interest, and forms the subject of constant discussion and complaint - entirely amongst ourselves, please take note, sir! Notwithstanding this general private discontent, we unfortunately as a body regard the existing state of things as inevitable, and have not sufficient courage, and do not know how if we had, to make a resolute stand against the injustice done us. I feel my position, sir, in this matter of giving information, to be one of peculiar difficulty. On the one hand, to be quite fair to myself and to those I am endeavouring to represent, I ought, and would like to describe fully and explicitly the exact kind of work done by us, the exact amount of it, and the exact price paid for that amount, and to give my own experience without reserve. But on the other hand, were I to do this I should be making revelations which would lead to instant recognition by many people of the particular factory in which I am employed, and probably also, sir, to the identification of your correspondent, which I shall do well to avoid. And therefore, on that account I feel reluctance to reveal them, greatly as I value this opportunity which you, sir, have so kindly given me of emphasising - for it must already be known - the fact that we are suffering from a great evil which stands in urgent need of redressing.

However, I think that even within the limits to which I shall have to restrict myself I can make good the statements contained in my first letter. I must explain before proceeding further that I shall speak of the branch of factory work known as "finishing". I have reason to believe that the other branches [of female employment] are not overpaid, but I shall speak only of what I know to be actual fact. With regard to wages. We are paid not by the hour or day, but a certain sum per garment. Wages, then, vary greatly. For instance, many different classes of work have to be done, and different prices are paid, not at all, however, in proportion to the amount of work to be done, for while one price may yield us as much as 3d an hour (occasionally), another will not yield us 1 1/2d an hour (quite frequently), working equally hard for each sum. Of course, all classes of work have to be done, and we have to accept with gratitude (or otherwise) whatever sum someone - our employer presumably - thinks it right to give us. We are doing excellently when earning 3d an hour. We not infrequently work for 1 1/2d an hour. An average of about 2d for the average 'hand' may be taken as fair. Occasionally we may get work which will yield us as much as 4 1/2d an hour, but it is so very occasional that it may be passed by in silence - otherwise, of course, we should have no cause for complaint.

And now to take an average of a year's wage of the 'average ordinary hand', which was the class I mentioned in my first letter, and being that which is in a majority may be taken as fairly representative. The wages of such a 'hand', sir, will barely average - but by exercise of the imagination - 8 shillings a week. I ought to say, too, that there is a minority, which is also considerable, whose wages will not average above 5 shillings a week. I would impress upon you that this is making the very best of the case, and is over rather than understating. What do you think of it, Mr. Editor, for a 'living' wage?

I wish some of those, whoever they may be who mete it out to us, would try to 'live' on it for a few weeks, as the factory girl has to do 52 weeks in a year. To pay board and lodging, to provide herself decent boots and clothes to stand all weathers, to pay an occasional doctor's bill, literature, and a holiday away from the scope of her daily drudging, for which even the factory girl has the audacity to long sometimes - but has quite as often to do without. Not to speak of provision for old age, when eyes have grown too dim to thread the everlasting needle, and to guide the worn fingers over the accustomed task. Yet this is a question which some of us, at least, ought to face, ignore it as we may, and are compelled to do. The census showing such a large preponderance of women over men in this country, it follows that the factory girl must inevitably contribute her quota to the ranks of old maidenism - be she never so willing to have it otherwise.

And now as to the number of hours worked to earn - or rather to get - this magnificent sum. I explained in my first letter that we are subject to fluctuations as to the amount of work supplied us. In other words that we have busy seasons and slack ones. It follows, then, that in busy seasons, to total up to the yearly average I have given, we make good wages - and, of course, work a proportionately long number of hours - and in slack seasons bad wages.

Now, sir, our working day - that is, in the factory - consists of from 9 to 10 hours. Take out of this time (often considerable and unavoidably so) to obtain the work, to obtain the 'trimmings' and materials to do it with, and then to get it 'passed' and booked in to us when done, and then calculate how much - say we are getting 2d an hour - we shall be able to earn in an ordinary working day in the factory. It will be plain that in order to average this wage we have in busy seasons to work longer than the actual time in the factory.

Home-work, then, is the only resource of the poor slave who has the misfortune to adopt "finishing" as a means of earning a livelihood. I have myself, repeatedly, five nights a week, besides Saturday afternoons, for weeks at a time, regularly taken four hours, at least, work home with me, and have done it. This, too, after a close hard day's work in the factory. In giving my own experience I give that of us all. We are obliged to do it, sir, to earn this living wage! It will be unnecessary to point out how fearfully exhausting and tedious it is to sit boring at the same thing for 14 or 15 hours at a stretch - meal times excepted of course.

But we are not asking for pity, sir, we ask for justice. Surely it would not be more than just to pay us at such a rate, that we could realise a living wage - in the true sense of the words - in a reasonable time, say one present working day of from 9 to 10 hours - till the eight hour day becomes general, and reaches even factory girls. Our work is necessary (presumably) to our employers. Were we not employed others would have to be, and if of the opposite sex, I venture to say, sir, would have to be paid on a very different scale. Why, because we are weak women, without pluck and grit enough to stand up for our rights, should we be ground down to this miserable wage ?

With regard to the conditions of our employment, those of which I can speak leave nothing to be desired. In the particular factory in which I am employed, we work in greatest freedom and comfort, and I should like to add, that as far as I personally am concerned, from those in immediate authority over me I have never received anything but consideration and courtesy.

In conclusion, sir, I am aware that in writing these letters to you I am probably doing what I was reading of the other day, namely, 'butting my head against a stone wall'; but, as the writer I am quoting went on to say, "How can one be sure it is a stone wall, or one made only of paper, unless one does butt one's head against it?" Now I am not quite sanguine enough to think that the wall against which I am butting my head will give way at least with my solitary "butt". Nevertheless, sir, I am determined to butt my head against it. Indeed, I feel it to be personally degrading and a disgrace upon me to remain silent and submit without a protest to the injustice done me.

And if the wall is of stone, sir, and the only remedy lies in the radical one recommended by the minority report of the Labour Commission, then will you allow me to urge upon your readers, upon those of my own sex who though not yet having the privilege of voting themselves, yet have influence with those who have, to use that influence intelligently, in the right direction? And to those of the opposite sex who do enjoy this privilege, to send only those men to Parliament, of whatever political creed, who stand pledged to do all in their power, with the utmost possible speed, to relieve the burden of the oppressed and suffering workers of this country, not least amongst whom are the factory girls of Crewe.

Question: Ada Nield Chew was one of a family of thirteen children. Her father was a brickmaker. Ada had to leave school at the age of eleven to help look after her younger brothers and sisters. When she wrote this letter Ada was 24 years old and working at the Compton Brothers clothing factory. As a result of her letter she lost her job. Explain the points made by Ada in her letter.

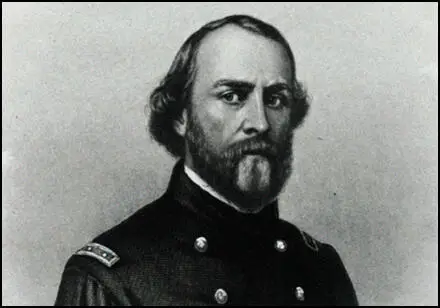

28th January, 2022: Major Sullivan Ballou, letter to Sarah Ballou (14th July, 1861)

The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days - perhaps tomorrow. Lest I should not be able to write you again, I feel impelled to write lines that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more.

Our movement may be one of a few days duration and full of pleasure - and it may be one of severe conflict and death to me. Not my will, but thine O God, be done. If it is necessary that I should fall on the battlefield for my country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American Civilization now leans upon the triumph of the Government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution. And I am willing - perfectly willing - to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this Government, and to pay that debt.

But, my dear wife, when I know that with my own joys I lay down nearly all of yours, and replace them in this life with cares and sorrows - when, after having eaten for long years the bitter fruit of orphanage myself, I must offer it as their only sustenance to my dear little children - is it weak or dishonorable, while the banner of my purpose floats calmly and proudly in the breeze, that my unbounded love for you, my darling wife and children, should struggle in fierce, though useless, contest with my love of country?

I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm summer night, when two thousand men are sleeping around me, many of them enjoying the last, perhaps, before that of death - and I, suspicious that Death is creeping behind me with his fatal dart, am communing with God, my country, and thee.

I have sought most closely and diligently, and often in my breast, for a wrong motive in thus hazarding the happiness of those I loved and I could not find one. A pure love of my country and of the principles have often advocated before the people and "the name of honor that I love more than I fear death" have called upon me, and I have obeyed.

Sarah, my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me to you with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence could break; and yet my love of Country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly on with all these chains to the battlefield.

The memories of the blissful moments I have spent with you come creeping over me, and I feel most gratified to God and to you that I have enjoyed them so long. And hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes of future years, when God willing, we might still have lived and loved together and seen our sons grow up to honorable manhood around us. I have, I know, but few and small claims upon Divine Providence, but something whispers to me - perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar - that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not, my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you, and when my last breath escapes me on the battlefield, it will whisper your name.

Forgive my many faults, and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless and foolish I have oftentimes been! How gladly would I wash out with my tears every little spot upon your happiness, and struggle with all the misfortune of this world, to shield you and my children from harm. But I cannot. I must watch you from the spirit land and hover near you, while you buffet the storms with your precious little freight, and wait with sad patience till we meet to part no more.

But, O Sarah! If the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near you; in the garish day and in the darkest night - amidst your happiest scenes and gloomiest hours - always, always; and if there be a soft breeze upon your cheek, it shall be my breath; or the cool air fans your throbbing temple, it shall be my spirit passing by.

Sarah, do not mourn me dead; think I am gone and wait for thee, for we shall meet again.

As for my little boys, they will grow as I have done, and never know a father's love and care. Little Willie is too young to remember me long, and my blue-eyed Edgar will keep my frolics with him among the dimmest memories of his childhood. Sarah, I have unlimited confidence in your maternal care and your development of their characters. Tell my two mothers his and hers I call God's blessing upon them. O Sarah, I wait for you there! Come to me, and lead thither my children.

Question: On 14th July, 1861, Major Sullivan Ballou heard that his regiment was about to engage the Confederate Army. He decided to write a letter to his wife Sarah in the expectation he might never have another opportunity. Seven days later he was hit by cannon ball during the battle of Bull Run. The world learned about this letter when it was featured in Ken Burns' acclaimed public television chronicle of the American Civil War (1990). Paul V. Hartman wrote in 1999: "What is remarkable about this letter is that, for the times, it was not remarkable, but for our times, with a hundred years of educational ruin in between, it is quite remarkable. Can you imagine a letter such as this being written in the times we now find ourselves?" Do you agree with Hartman's comments?

27th January, 2022: Christabel Pankhurst described the arson campaign in her book Unshackled: the Story of how we Won the Vote (1959)

Many militants had been restive for some time, considering that it would be more dignified to anticipate the sorry outcome of the Government's now broken pledge than await it passively. As leaders, we had felt bound to restrain this eagerness, but now there was no reason for delay. The ingenuity and the pertinacity of the Suffragette guerillists were extraordinary. Never a soul was hurt, but the struggle continued.

Golf greens suffered on one occasion by the carving on the turf of "Votes Before Sport" and "No Votes, No Golf'!" The editor of Golfing complained on the plea that "golfers are not usually very keen politicians." "Perhaps they will be now," said the Suffragettes.

The damage done to property was more spectacular than serious. Museums began to be closed, here and there, with preventive caution, to the vexation of American visitors. Mr. Lloyd George's house at Walton Heath paid the price of its owner's deed.

Question: The Women's Social and Political Union began its controversial arson campaign in 1912. How does Christabel Pankhurst justify the campaign?

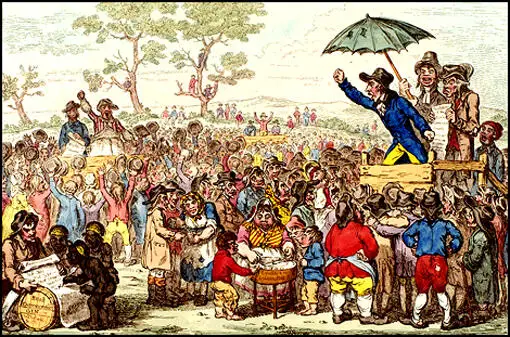

26th January, 2022: Resolutions passed by the London Corresponding Society in January, 1793.

(I) That nothing but a fair, adequate and annually renovated representation in Parliament, can ensure the freedom of this country.

(II) That we are fully convinced, a thorough Parliamentary Reform, would remove every grievance under which we labour.

(III) That we will never give up the pursuit of such Parliamentary Reform.

(IV) That if it be a part of the power of the king to declare war when and against whom he pleases, we are convinced that such power must have been granted to him under the condition, that he should ever be subservient to the national advantage.

(V) That the present war against France, and the existing alliance with the Germantic Powers, so far as it relates to the prosecution of that war, has hitherto produced, and is likely to produce nothing but national calamity, if not utter ruin.

(VI) That it appears to us that the wars in which Great Britain has engaged, within the last hundred years, have cost her upwards of three hundred and seventy million! not to mention the private misery occasioned thereby, or the lives sacrificed.

(VII) That we are persuaded the majority, if not the whole of those wars, originated in Cabinet intrigue, rather than absolute necessity.

(VIII) That every nation has an unalienable right to choose the mode in which it will be governed, and that it is an act of tyranny and oppression in any other nation to interfere with, or attempt to control their choice.

(IX) That peace being the greatest blessing, ought to be sought most diligently by every wise government.

(X) That we do exhort every well wisher to this country, not to delay in improving himself in constitutional knowledge.

Question: In 1792 only 5% of the population of Britain could vote in elections. Read these resolutions and explain why the London Corresponding Society (LCS) believed in votes for all adult males. How did the government respond to these demands?

xx

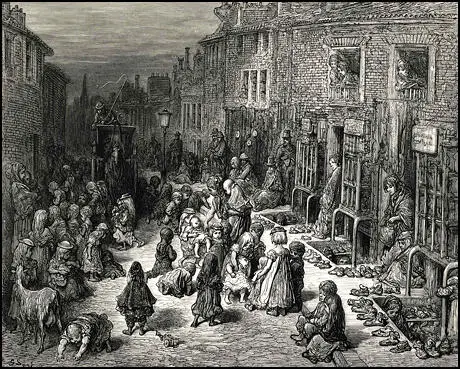

25th January, 2022: Edwin Chadwick, The Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population (1842)

The annual loss of life from filth and bad ventilation are greater than the loss from death or wounds in war which the country has been engaged in modern times.

The primary and most important measures, and at the same time the most practicable, and within the recognized province of public administration, are drainage, the removal of all refuse of habitations, streets, and roads, and the improvements of the supplies of water.

That by the combinations of all these arrangements it is probable that an increase of 13 years at least, may be extended to the whole of the labouring classes.

Question: Edwin Chadwick's report, The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population, was published in 1842. Chadwick argued that slum housing, inefficient sewerage and impure water supplies in industrial towns were causing the unnecessary deaths of about 60,000 people every year. Why did Chadwick claim: "The expense of public drainage, of supplies of water laid on in houses, and the removal of all refuse... would be a financial gain."?

24th January, 2022: Emanuel Celler, You Never Leave Brooklyn (1953)

My grandfather, in 1848, had fled from Germany to find political freedom in the United States. My grandfather was Catholic; my grandmother, Jewish. I have heard the story of their meeting so many times that it has taken on the form of a ballad. Crossing over from Bavaria, as immigrants to the United States, they did not meet on board ship. Outside of New York Harbor, the ship started to sink. My grandmother jumped overboard. My grandfather followed, to save this girl he had never met. Save her he did.

In our house we repeated the pattern of thousands of other homes. There were a few books and a lot of music. Our food and our furniture were no different from our neighbors'. While we ourselves were not poor, I had only to walk a few streets away to find the sounds and the smells of poverty. We were respectable and middle-class. But we were not very far from the Brooklyn dockyards. I didn't know then that I would never be able to leave the sounds and smells of these sights behind me, but I was fiercely conscious of one thing - of my ambition. Where it would take me and where I would go, I didn't know.

I read whatever I could put my hands to. I became the "scholar" of the family. I became, too, more than just a bit of a snob. The studied, unquestioning pace of my family irritated me. There were "things" to be done. Nobody asked me what I meant by "things." I couldn't have defined them if I had tried. "Things" had to do with the study of music (this was a family interest), the books I read, and the dreams of travel, and the glimpses of elegance I caught on Fifth Avenue. But "things" had also to do with the way people were hurt and how, because they were hurt, they were angry and quarreled and were jealous of one another...

For the first ten years of my life in Congress, I had been timid. I had been too timid to tell the truth as I saw it. In a way I had betrayed my trust. Yes, I had fought against the unjust restriction of immigration. I worked what seemed to me endlessly on the repeal of the Prohibition Amendment. I had advocated the establishment of a Negro industrial commission. I had gestured against the growth of monopoly power. I had introduced a few civil rights bills. But, actually, I had taken on the color of the climate around me and I had driven back all the emotion that rose from the Brooklyn streets, so that I could belong unobtrusively to the exclusive club of Congress.

The panic of the depression loosened my inhibitions against being different. For the first time in ten years I could be myself. I realized that there were some things I cared about passionately. One of them was independence for India; another, the establishment of the National Homeland for the Jews in Palestine; another was our immigration laws; and the fourth was economic freedom for the people of the United States as against the growth of monopoly power stifling that freedom.

Question: Emanuel Celler was one of the most progressive politicians in Congress. (a) How did his background influence his politics? (b) Why was he not as radical as he hoped to be?

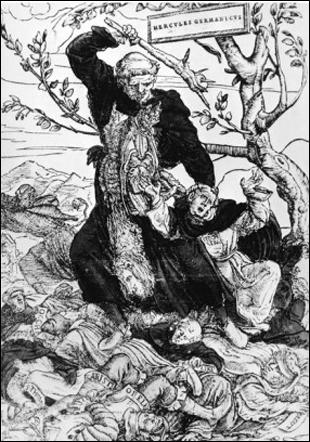

21st January, 2022: Martin Luther, An Earnest Exhortation for all Christians, Warning Them Against Insurrection and Rebellion (December 1521)

Now it seems probable that there is danger of an insurrection, and that priests, monks, bishops, and the entire spiritual estate may be murdered or driven into exile, unless they seriously and thoroughly reform themselves. For the common man . . . is neither able nor willing to endure it longer, and would indeed have good reason to lay about him with flails and cudgels, as the peasants are threatening to do ...

According to the Scriptures such fear and anxiety come upon the enemies of God as the beginning of their destruction. Therefore it is right, and pleases me well, that this punishment is beginning to be felt by the papists who persecute and condemn the divine truth. They shall soon suffer more keenly ... Already an unspeakable severity and anger without limit has begun to break upon them. The heaven is iron, the earth is brass. No prayers can save them now. Wrath, as Paul says of the Jews, is come upon them to the uttermost. God's purposes demand far more than an insurrection. As a whole they are beyond the reach of help... The Scriptures have foretold for the pope and his followers an end far worse than bodily death and insurrection.

Question: Martin Luther was sympathetic to their plight of peasants in Germany and attacked the oppression of the landlords. Thomas Müntzer was a follower of Luther and argued that his reformist ideas should be applied to the economics and politics as well as religion. Müntzer began promoting a new egalitarian society. Frederick Engels wrote that Müntzer believed in "a society with no class differences, no private property and no state authority independent of, and foreign to, members of society". In August 1524, Müntzer became one of the leaders of the uprising later known as the Peasants’ War.

Why did some people claim that Martin Luther's An Earnest Exhortation for all Christians, Warning Them Against Insurrection and Rebellion (December 1521) helped to encourage the Peasants’ War.

20th January, 2022: Jennie Lee was a student at Edinburgh University when her father, a miner, was involved in the General Strike. Lee wrote about it in her book, My Life With Nye (1980).

Although the General Strike lasted only ten days the miners held out from April until December. Until the June examinations were over I was chained to my books, but I worked with a darkness around me. What was happening in the coalfield? How were they managing? Once I was free to go home to Lochgelly my spirits rose. When you are in the thick of a fight there is a certain exhilaration that keeps you going.

Stanley Baldwin promised that there would be no victimization when the miners went back to work. That was one more piece of deliberate deception. My father was not reinstated - from four months he trudged from pit to pit, turned away everywhere. Uncle Michael was also victimized, and so sadly he came to the decision that the only thing to do was to go off to America.

Question: In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservatives who depended on secret donations from rich men."

The legislation defined all sympathetic strikes as illegal, confining the right to strike to "the trade or industry in which the strikers are engaged". The funds of any union engaging in an illegal strike was liable in respect of civil damages. It also limited the right to picket, in terms so vague that almost any form of picketing might be liable to prosecution. As Julian Symons has pointed out: "More than any other single measure, the Trade Disputes Act caused hatred of Baldwin and his Government among organized trade unionists."

One of the results of this legislation was that trade union membership fell below 5,000,000 for the first time. Some historians have suggested that Stanley Baldwin and his government made a mistake by passing this legislation. What evidence would they need to support this point of view?

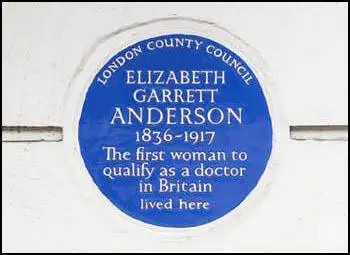

19th January, 2022: In 1939, Louisa Garrett Anderson, the daughter of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, wrote about attitudes towards girls' education in the 19th century.

Men were believed to dislike 'blue-stockings', so that parents thought the serious education of their daughters superfluous: deportment, music and a little French would see them through. 'To learn arithmetic will not help my daughter to find a husband was a common point of view. A governess at home, for a short period, was the usual fate of the girls. Their brothers might go to public schools and university but home was considered the right place for their sisters. Some parents sent their daughters to a finishing school, but good schools for girls did not exist. Their teachers were untrained and ill-educated. No public examinations accepted female candidates.

To his daughters, Newson Garrett opened up the windows of the world by sending them to boarding school… He took trouble in the choice of school. Finally it was decided that Louie and Elizabeth should go on to an 'Academy for the Daughters of Gentlemen' at Blackheath, kept by Miss Browning and her sister… After two years at Blackheath, Louie and Elizabeth left, their education considered to be at an end.

Question: Why was it so difficult for daughters of wealthy parents to get a good education in the 19th century? It might help you to read Women and Schooling.

Edward Baines' book The History of the Cotton Manufacture (1835)

18th January, 2022: John Fielden, speech in the House of Commons (9th May, 1836)

At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock beside me, I watched a child at her work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it to be nothing short of twenty miles.

Question: Charles Wing, wrote in Evils of the Factory System (1837) "Mr. Fielden's cotton-mill at Todmorden employs 840 hands. The labour is sixty-seven hours and a half week, being an hour and a half less than most others. No children were employed under nine. A school is attached to the mill. If the liberal management pursued in Mr. Fielden's mill were generally adopted, there would be few evils to complain of." Why would a factory owner campaign against the employment of children?

17th January, 2022: The Spectator (25th January, 1862)

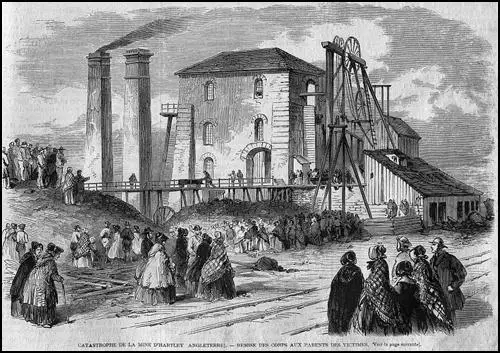

The Hartley Colliery has been gazing throughout the week on a tragedy which, in its extent, and character, and duration, its accumulation of all the circumstances which can deepen and intensify horror, is almost without a parallel. Men recoil always before masses of helpless suffering, though happily no man can share his neighbour's death, and here was an entire community, two hundred and fifteen souls, all heads of households and young boys, swept away in one tremendous, yet slow-moving calamity. There have been catastrophes as widespread, such as those caused by earthquakes or avalanches, but they have at least been sudden. The miners at Hartley Colliery were being buried alive during seven long days, during all which time exertion and watchfulness never ceased, and agony was perpetually renewed by flashes of a deceptive hope. The awful visibleness of the disaster, that tone of the amphitheatre which the telegraph imparts to every occurrence prolonged enough for its ministration, adds to the calamity the effect which, henceforth, will give the last touch of misery to every such scene. Mothers, and kinsfolk, and fellow-workmen, could, as it were, all see the approach of the frightful death they could not prevent, and all England, as the telegrams dribbled in hour by hour, felt as if watching a torture-chamber, and chafed at its power-lessness to relieve.

There was, perhaps, nobody to blame, and we question if that fact did not greatly increase the sadness of all observers. Men would rather suffer by human default than by an accident of this kind, by a break, as it were, in that system of Providential guardianship on which consciously or unconsciously they rely for protection. Even the carelessness which, as we have explained in another column, was the probable occasion of the accident, was not its cause. Hartley Colliery has one main shaft, and the great iron beam or lever which draws up the water from its depths, the arm, as it were, of the steam-pump, broke and fell in, carrying beams and bratticing, and the sides of the shaft itself, into the depths below. In ordinary cases such an accident even as this would at the utmost have cost only the lives of the men actually in the shaft. That the falling ruin should jam itself half way down, and so close, as it were, the gate of an entire mine, was a misfortune without a precedent. From the moment the accident occurred there was no want of energy, or judgment, or courage. The viewers did all that experience could suggest, volunteers were ready in scores, and the pitmen were only too eager in their determination not to allow despair to retard the progress of the work. Still, cutting through a closed well is the most tedious of all processes, and so, hour after hour, and day after day, the obstruction was removed, as it were, in handfuls, the workers being cheered for five of the seven days by sounds which gave them hope that the sufferers were alive. They might have been rescued, for they seem to have had food - some corn kept for a pony - and we may hope light; but the mine began in the absence of outer air to generate gas, and on the fifth day, at latest, the whole of the buried miners, arranged in groups, family by family, brother clasping brother, all perished, in most cases without a struggle. Not one escaped, and when the workmen at last reached the scene, penetrating themselves through gases which threatened their lives, they found only corpses laid as if in some gigantic natural tomb, and seem to have felt a relief in the certainty that the victims had not died of starvation. There is one lesson to be learnt from the case, that every pit ought to have two places of exit: otherwise the occurrence, like an earthquake or the fall of an avalanche, only teaches how vain all precautions are against those great forces of nature which man yet has the courage to defy, and the reason usually to evade.

Question: The Spectator article is describing one of the worst mining disaster when 204 men were killed when the beam of the pit's pumping engine broke and fell down the shaft, trapping the men below. The Miners Association of Great Britain campaigned against dangerous working conditions in the 19th century. Accidents in shafts caused by rope and chain breakages, flooding, fires and roof falls continued to kill large numbers of miners. Official statistics were not kept, and powerful colliery owners were often successful at persuading local newspapers not to report the deaths of coal-miners. By studying all the statistics that are available, one historian has calculated in some collieries in the 19th century, workers had a 50% chance of being killed in a mining accident. Why did the number of miners killed in accidents fall in the 20th century?

14th January, 2022: Muriel Simkin, was 24 years-old when she began working in a munitions factory in Dagenham during the Second World War.

We had to wait until the second alarm before we were allowed to go to the shelter. The first bell was a warning they were coming. The second was when they were overhead. They did not want any time wasted. The planes might have gone straight past and the factory would have stopped for nothing.

Sometimes the Germans would drop their bombs before the second bell went. On one occasion a bomb hit the factory before we were given permission to go to the shelter. The paint department went up. I saw several people flying through the air and I just ran home. I was suffering from shock. I was suspended for six weeks without pay.

They would have been saved if they had been allowed to go after the first alarm. It was a terrible job but we had no option. We all had to do war work. We were risking our lives in the same way as the soldiers were.

Question: It has been claimed that a woman working in a munitions factory had more chance of being killed than a man in the British Army. Explain why working in a munition factory was so dangerous?

13th January, 2022: Mary Borden, The Forbidden Zone (1929)

It was my business to sort out the wounded as they were brought in from the ambulances and to keep them from dying before they got to the operating rooms: it was my business to sort out the nearly dying from the dying. I was there to sort them out and tell how fast life was ebbing in them. Life was leaking away from all of them; but with some there was no hurry, with others it was a case of minutes. It was my business to create a counter-wave of life, to create the flow against the ebb.

If a man were slipping quickly, being sucked down rapidly, I sent runners to the operating rooms. There were six operating rooms on either side of my hut. Medical students in white coats hurried back and forth along the covered corridors between us. It was my business to know which of the wounded could wait and which could not. I had to decide for myself. There was no one to tell me. If I made any mistakes, some would die on their stretchers on the floor under my eyes who need not have died. I didn't worry. I didn't think. I was too busy, too absorbed in what I was doing. I had to judge from what was written on their tickets and from the way they looked and they way they felt to my hand. My hand could tell of itself one kind of cold from another. My hands could instantly tell the difference between the cold of the harsh bitter night and the stealthy cold of death.

Question: The government established Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) to provide medical assistance in time of war. By the summer of 1914 there were over 2,500 VADS in Britain. Of the 74,000 VADs in 1914, two-thirds were women. How does Mary Borden's account illustrate the problems faced by VADs?

12th January, 2022: May Billinghurst, account of being force-fed in Holloway Prison in January, 1913.

I just laid on my back and endured it all - on Sunday I was very weak and on Sunday night I tried to get out to the bell because my head was swimming round so I fell on the floor and fainted... My head was forced back and a tube jammed down my nose. It was the most awful torture. I groaned with pain and I coughed and gulped the tube up and would not let it pass down my throat. Then they tried the other nostril and they found that was smaller still and slightly deformed, l suppose from constant hay-fever. The new doctor said it was impossible to get the tube down that one so they jammed it down again through the other and I wondered if the pain was as bad as child-birth. I just had strength and will enough to vomit it up again and I could see tears in the wardresses' eyes.

Question: Fran Abrams, wrote in Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003) that May Billinghurst was known as "The Cripple Suffragette" and that her "hand-propelled invalid tricycle gave her a special advantage in the propaganda battle they were waging". Explain what Abrams means by this? How would Billinghurst account of being forced-fed be used in the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) propaganda campaign?

11th January, 2022: Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929)

Sampson lay groaning about twenty yards beyond the front trench. Several attempts were made to rescue him. He was badly hit. Three men got killed in these attempts: two officers and two men, wounded. In the end his own orderly managed to crawl out to him. Sampson waved him back, saying he was riddled through and not worth rescuing; he sent his apologies to the company for making such a noise. At dusk we all went out to get the wounded, leaving only sentries in the line. The first dead body I came across was Sampson. He had been hit in seventeen places. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death.

Question: Robert Graves wrote about what happened when a popular officer was wounded in No Mans Land. Can you explain why publishers were not willing to publish soldier memoirs until ten years after the war came to an end.