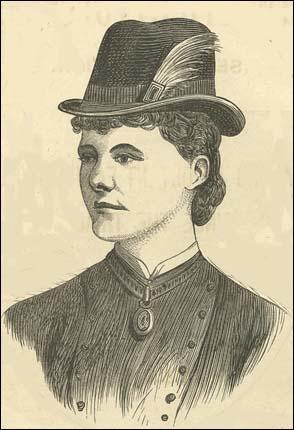

Emilia Dilke

Emilia Francis Strong, the fourth of the six children of Henry Strong, a retired Indian army officer, and his wife, Emily Weedon Strong, was born in Ilfracombe on 2nd September 1840. She was educated at home and her tutor gave her a good education in French, German, Latin, and Greek. (1)

Emilia came from an artistic family and as a young women she met John Ruskin, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt (who proposed to her in 1859, but was rejected). Ruskin encouraged her to study at the Government School of Design in South Kensington where she became was a student for two years. (2)

Emilia Strong was a good student, with a special interest in anatomical drawing. As a woman, she was denied access to formal life-drawing classes at South Kensington, but in 1859, defying convention, she took private tuition from William Mulready in drawing from the nude. "Like a number of other female artists of the day, she protested against the exclusion of women from what was considered to be the most prestigious area of art education. She later withdrew an offer to found a scholarship for female art students at the Royal Academy Schools when the authorities refused to concede to her condition that the women's education include drawing from the nude". (3)

Edward Poynter, the first principal of the Slade School of Art, pointed out: "There is unfortunately a difficulty which has always stood in the way of female students acquiring that thorough knowledge of the figure which is essential to the production of work of a high class; and that is, of course, that they are debarred from the same complete study of the model that is open to the male students... But I have always been anxious to institute a class where the half-draped model might be studied, to give those ladies who are desirous of obtaining sound instruction in drawing the figure, an opportunity of gaining the necessary knowledge." (4)

Marriage to Mark Pattison

In June 1861 Emilia Strong became engaged to the 48-year-old scholar Mark Pattison, the rector of Lincoln College. The couple were married on 10th September 1861. The Pattisons' marriage was very unhappy and led her to spend increasing periods of time in France where she continued her study of art. She also wrote for a variety of journals on the subject. This included an article, Art and Morality for the Westminster Review. (5)

In 1872 she became secretary of the Oxford branch of the National Society for Women's Suffrage. Emilia became in the first women's trade union, the Women's Protective and Provident League (later named Women's Trade Union League). Founded by Emma Paterson, the union represented dressmakers, upholsterers, bookbinders, artificial-flower makers, feather dressers, tobacco, jam and pickle workers, shop assistants and typists. (6)

Emilia continued to write about art and in 1873 she was employed as editor of The Academy. She was also the author of The Renaissance of Art in France (1879). As Hiliary Fraser has pointed out, "the hallmarks of her scholarship are already evident: her meticulous archival research into primary and unpublished sources; her interest in the institutional organization of the arts, and in the political, economic, and social conditions under which they were produced; and her deep conviction of the profound connectedness of the works of decoration, furniture, painting, engraving, sculpture, and architecture of a period". (7)

In 1882 she published a biography of Frederic Leighton. Emilia did not follow the widespread convention of journalistic anonymity, and published under the signature "E. F. S. Pattison". It was claimed that the ‘S’ referred to her family name Strong, as it was her "her wish for some recognition of the independent existence of the woman, and in some resistance to the old English doctrine of complete merger in the husband". (8)

Mark Pattison died on 30th June, 1884. Soon afterwards she became involved with Charles Wentworth Dilke, a member of the government led by William Gladstone. Dilke had for a long time been a supporter of women's suffrage. Dilke was one of the most left-wing members of the Liberal Party and had upset the House of Commons with several speeches complaining about the cost of the royal family and suggested that the country should debate the merits of the monarchy. (9)

Virginia Crawford Divorce Case

In June 1885 Gladstone resigned after supporters of Irish Home Rule and the Conservative Party joined forces to defeat his Liberal government's Finance Bill. Gladstone was expected to retire from politics and Dilke was considered to be a possible candidate for the leadership. This speculation came to an end when Virginia Crawford, the 22-year-old wife of Donald Crawford, a lawyer, and also Dilke's brother's sister-in-law. Virginia claimed that Dilke seduced her in 1882 (the first year of her marriage) and had then conducted an intermittent affair with her for two and a half years. Virginia also told her husband that Dilke had involved her in a ménage-à-trois with a servant girl, Fanny Grey (she denied the story). Virginia said she had resisted this but the MP, whom she portrayed as a sexual monster, forced her to co-operate. "He taught me every French vice," she said. "He used to say that I knew more than most women of 30." (10)

Donald Crawford sued for divorce, and the case was heard on 12th February 1886. Virginia Crawford was not in court, and the sole evidence was her husband's account of Virginia's confession. There were also some accounts by servants, which were both circumstantial and insubstantial. Dilke resolutely denied the charges, although his position was complicated from the beginning by the fact that he had, both before and after his first marriage, been the lover of her mother, Martha Mary Smith. Dilke was advised by his legal team not to give evidence in court. (11)

Betty Askwith has pointed out that "as English law stood... a wife’s confession to her husband is evidence of her guilt but did not carry the corollary that the co-respondent whom she accuses is also guilty". (12) As a result the judge ruled that "I cannot see any case whatsoever against Sir Charles Dilke" and ordered Crawford to pay the costs but Virginia was found guilty and the judge granted Crawford his divorce. The judge appeared to be saying "that Mrs. Crawford had committed adultery with Dilke, but that he had not done so with her". (13)

The Spectator reported that the case could bring an end to his political career: "There was no corroboration of those charges, except as to a few dates; and for all that was proved, they might be mere inventions, or the dreams of a woman suffering from a well-known form of hallucination. But then, there was no disproof, and the Judge accepted the confession as substantially true. Sir Charles Dilke's counsel called no witnesses, attempted no cross-examination of Mr. Crawford, and advised their client not to enter the witness-box, and so defend both himself and Mrs. Crawford, lest 'early indiscretions should be raked up,' - obviously a mere excuse. The world is tolerant enough, if not over-tolerant, and no indiscretions could have hurt Sir Charles Dilke as the confession if proved would do. As a result, Mr. Justice Butt, while expressly stating that he believed Mr. Crawford's report of the confession, accepted the confession itself as so true, that though almost uncorroborated, be founded on it a decree of divorce against Mrs. Crawford". (14)

William T. Stead began a campaign against Dilke for not going into the witness box. By April this had persuaded him that he should seek to reopen the case by getting the Queen's Proctor to intervene. The second inquiry began on 16th July 1886. Dilke falsely assumed that his counsel would be able to submit Virginia Crawford to a devastating cross-examination. Instead, both witnesses were examined by the Queen's Proctor. Christina Rogerson also gave evidence and testified that Virginia Crawford had both confessed her adultery with Dilke and conducted another adulterous relationship with Captain Henry Forster, sometimes meeting him at Rogerson’s home. Under oath, Virginia Crawford confirmed her friend’s evidence - and also informed the court that Dilke had told her that Rogerson was another of his ex-mistresses. (15)

Dilke's biographer, Roy Jenkins, has argued: "The result was a disaster. He proved a very bad witness, she a very good one. The summing up by the president of the Probate, Divorce, and Admiralty Division was highly unfavourable to Dilke. The verdict of the jury - in form that the divorce should stand, in fact that Mrs Crawford was a witness of the truth and that Dilke was not - was reached quickly and unanimously". Jenkins is convinced that Virginia Crawford lied in court and was part of a conspiracy to end his political career. (16)

Some newspapers called for Charles Dilke to be prosecuted for perjury. "The sickening details of the Crawford divorce case, which ended yesterday with a verdict in favour of Mr. Crawford, in other words, against Sir Charles Dilke. If that verdict be true, Sir Charles Dilke must have been guilty of a particularly base form of perjury, and for perjury, of course, he must at once be prosecuted... That any man should escape without heavy punishment for the guilt of all these perjuries, which, if perjuries at all, are perjuries of the very meanest and basest kind, perjuries not committed in defence of the woman he had seduced, but for the purpose of making her seem even worse than she really was, would be a scandal to English justice of which it is hardly possible that this generation would exhaust all the miserable consequences". (17)

Brian Cathcart, recently investigated the case and believes that Charles Dilke was innocent of the charges. "This is not to say that the Liberal politician was pure as driven snow. Aged 42 at the time and single, he was known as a ladies' man and among his previous paramours was Virginia's mother. But Virginia also had a sexual track record. The daughter of a Tyneside shipbuilder, at the age of 18 she had been forced against her will to marry Donald Crawford, a man twice her age. With a married sister, Helen, she then set about finding consolation with lovers, particularly among the medical students at St George's Hospital. Both she and Helen also had affairs with an army captain, Henry Forster, whom they met frequently at a brothel in Knightsbridge, and Dilke's friends later produced evidence that the two young women shared the attentions of several men, possibly in the same bed at the same time."

Cathcart then goes on to explain why he was framed: "Various theories have circulated. Politically, he was important and controversial and many people, Liberal and Tory, were glad to see him fall. Queen Victoria was particularly amused, as he was the leading republican of his time.... Virginia was desperate for a divorce, but in the hope of avoiding publicity about her sexual past and of protecting her true lover, Forster, she decided to name some other, innocent man. Her choice fell on Dilke because of his past relationship with her mother and because she was encouraged by a friend, Christina Rogerson, who felt she had been jilted in love by Dilke." (18)

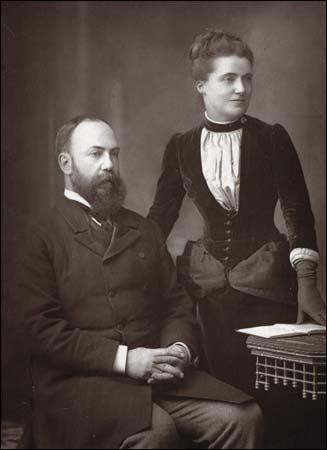

Marriage to Charles Wentworth Dilke

It is believed that one of the reasons that Christina Rogerson gave evidence against Dilke is that she expected to become his wife. However, when she realised he planned to marry Emilia, she decided to give evidence against him in the divorce case. Emilia married on 3rd October 1885.

In 1886, on the death of Emma Paterson, Emilia became president of the Women's Trade Union League. Emilia said she was proud "to fill the post of leader in a crusade against the tyranny of social tradition and the callousness of social indifference" and over the next few years she spoke "at public meetings across the country, regularly attending and addressing the annual Trades Union Congress as part of her promotion of male-female working-class co-operation and writing for the league's papers and the general press." (19)

Charles Wentworth Dilke lost his seat at the 1886 General Election. Although he had been a long-term campaigner for women's rights, a group of women activists, including Annie Besant, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Elizabeth Blackwell, Frances Buss and Eva McLaren, tried to prevent him from returning to the House of Commons. (20)

Emilia and Charles Dilke were close friends of Richard Pankhurst and his wife Emmeline Pankhurst and they both continued to give money to organisations supporting women's suffrage. However, many of the leaders of the movement did not want to be associated with Dilke because of the Crawford case. Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy felt very strongly about this as "she was clearly not at all in sympathy with his unorthodox extra-marital history." (21)

Emilia Dilke continued to publish books on painting including Art in the Modern State (1888) and her most ambitious work, an encyclopaedic four-volume study of eighteenth-century French art, where she sought "to trace the action of those social laws under the pressure of which the arts take shape". (22)

In 1892 Charles Dilke was elected to represent the Forest of Dean. Dilke retained his radical beliefs and over the next ten years he continued to advocate progressive policies: "He achieved great local popularity, particularly with the miners of what was then a detached but significant small coalfield. He vigorously pursued their interests and those of labour generally, as well as being an independent parliamentary expert on military, colonial, and foreign questions, and was an important link with Labour members and trade unionists". (23)

Charles and Emilia were more concerned with universal suffrage than any limited enfranchisement of women. The main reason for this was the fear that most middle-class women would vote for the Conservative Party. In 1903 she left the Liberal Party and joined the Independent Labour Party. (24)

Emilia Dilke, aged sixty-four, died following a brief illness on 24th October 1904 at her Surrey house, Pyrford Rough near Woking.

Primary Sources

(1) Hiliary Fraser, Emilia Francis Dilke : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

After completing her art education, Strong returned to Oxford, where she became engaged to the 48-year-old scholar Mark Pattison (1813–1884), rector of Lincoln College, in June 1861, and married him at Iffley church on 10 September 1861. Despite her intellectual marginalization as a woman in Oxford, Francis Pattison entered upon a life of serious scholarship, focusing upon the study of French cultural history and art. At the same time she cut a striking figure socially, developing an artistic and intellectual circle more in keeping with the salons of seventeenth-century France—upon which she was establishing herself as an authority—than with the stuffy masculine culture of Oxford college life. According to contemporary accounts, and on the evidence of the early portrait of Mrs Pattison painted by her friend Pauline, Lady Trevelyan, in 1864, her dress and general demeanour were particularly stylish and picturesque. The Pattisons' marriage was famously unhappy, allegedly the model for the mésalliances of Dorothea Brooke and Edward Casaubon in George Eliot's Middlemarch (1871–2) and of Belinda and Professor Forth in Rhoda Broughton's Belinda (1883), and a possible source for Robert Browning's poem ‘Bad Dreams’ in Asolando (1889). Its miseries, and her own ill health, led Pattison to spend increasing periods of time in France, where she was able to pursue her research interests with greater resources and more independence...

It was under this name that Pattison published her first book, The Renaissance of Art in France (1879), in which the hallmarks of her scholarship are already evident: her meticulous archival research into primary and unpublished sources; her interest in the institutional organization of the arts, and in the political, economic, and social conditions under which they were produced; and her deep conviction of the profound connectedness of the works of decoration, furniture, painting, engraving, sculpture, and architecture of a period.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)