On this day on 11th August

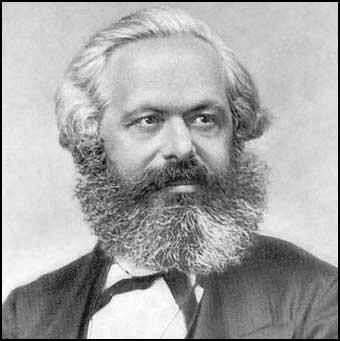

On this day in 1844 Karl Marx, thanks Ludwig Feuerbach for converting him to socialism. "I am glad to have an opportunity of assuring you of the great respect and - if I may use the word - love which I feel for you... You have provided - I don't whether intentionally - a philosophical basis for socialism... The unity of man with man, which is based on the real differences between men, the concept of the human species brought down from the heaven of abstraction to the real earth, what is this but the concept of society."

On this day in 1914 David Lloyd George, letter to his wife telling her that did not want his own twenty-year old son, Gwilym Lloyd George, to join the army. He wrote to his wife explaining his own position: "They are pressing Territorials to volunteer for the War. Gwilym mustn't do that yet... I am dead against carrying on a war of conquest to crush Germany for the benefit of Russia... I am not going to sacrifice my nice b(3)

David Lloyd George was asked to use his great skills as an orator to persuade men to join the armed forces. On 19th September, he spoke at the Queen's Hall in London. "There is no man in this room who has always regarded the prospect of engaging in a great war with greater reluctance and with greater repugnance than I have done through the whole period of my political life. There is no man inside or outside this room more convinced that we could not have avoided it without national dishonour... They think we cannot beat them. It will not be easy. It will be a long job. It will be a terrible war. But in the end we will march through terror to triumph. We shall need all our qualities - every quality that Britain and its people possess - prudence in counsel, daring in action, tenacity in purpose, courage in defeat, moderation in victory, in all things faith."

Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, wept when he read the speech. Asquith told him that it was a wonderful speech and Charles Masterman claimed it was "the finest speech in the history of England". The speech was also praised by the Conservative Party supporting newspapers, who described the man who they had been attacking for many years as a "British patriot". By the end of the month over 750,000 men had enlisted in the British armed forces.

H. H. Asquith was shocked and surprised when his three sons, Cyril (24), Arthur (31) and Herbert (33) immediately joined the armed forces. Herbert pointed out "England expects every man to do his duty" and if they did not offer their services "Father will be asked why he doesn't begin his recruiting at home". Arthur agreed and was the first to join: "I have two older brothers, both married, and one younger brother with an ailing colon... It is obviously fitting that one of my father's four sons ought to be prepared to fight".

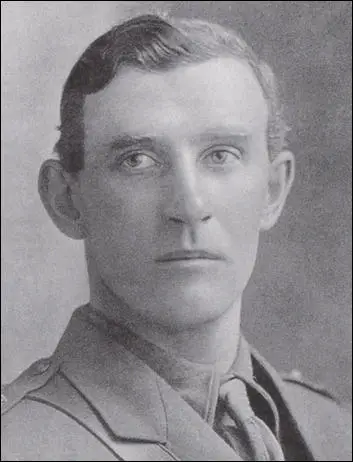

However, his eldest son, Raymond Asquith, was nearly 36 and was married with two young children, made a different decision. A highly successful lawyer, he was less enthusiastic about the war than his younger brothers. Raymond was on the left of the Liberal Party and had doubts about the wisdom of declaring war on Germany. He had no confidence in Lord Kitchener, who he described as the "King of Chaos" and expected the war to last at least three years and predicted that "sooner or later they (his brothers) would all be under the turf".

H. H. Asquith was pleased that his eldest son had refused to join the armed forces. He was being groomed to become a leading political figure. In 1913 he had been adopted as Liberal Party candidate for Derby, where the sitting member was retiring. John Buchan thought he would be a great success as a politician: "He had every advantage in the business - voice, language, manner, orderly thought, perfect nerve and coolness... Though he might scoff at most dogmas, he had a great reverence for the problems behind them, and to these problems he brought a fresh mind and a sincere goodwill." His brother, Herbert Asquith, commented "he was a brilliant speaker, and if he had entered the House, there is little doubt that he would have made his presence felt."

Despite his doubts about the war, Raymond Asquith joined the Queen's Westminster Rifles in January 1915. His father, was furious with him for making this decision. "As the months went by with no sign of the regiment being sent abroad, Raymond... became increasingly frustrated with such futile tasks as stopping suspicious vehicles approaching London from the North-West." His wife, afraid that he would seek to serve abroad, tried to convince him to stand as a Liberal Party candidate in a by-election, but he rejected the idea as he saw it as an act of cowardice.

Aware that he would not see active service in this regiment he transferred as a lieutenant into the 3rd battalion of the Grenadier Guards and went out to the Western Front in October, 1915. His stepmother, Margot Asquith, wrote: "Raymond left this morning... I was almost surprised at how sad I felt at parting with him - there was something so pathetic and incongruous in seeing so perfect and highly finished a being going off into that raw brutal primitive hurly-burly."

Asquith was furious with his son and refused to write to him while he was on the Western Front. However, he was posted to one of the comparatively quiet sections of the front line, where shelling was sporadic. He wrote to his friend, Diana Manners, that he was more concerned by the discomfort than the danger, complaining about "being up to his neck in dense, sticky blue clay; at the same time he was puzzled that while the sound of rifle fire seemed no more far off than the next gun in a partridge drive".

In an early letter to his wife from the front he complained about the lack of dry trenches and the failures of the authorities in making no adequate preparations for winter, claiming that half of his men did not have trench boots. He also noted the contempt felt for staff officers behind the lines by those in the trenches, and felt that she would think he was right not to become one, "though of course one may find in the end that there are more uncomfortable things than general abuse".

On the Western Front in December 1914 there was a spontaneous outburst of hostility towards the killing. On 24th December, arrangements were made between the two sides to go into No Mans Land to collect the dead. Negotiations also began to arrange a cease-fire for Christmas Day. On other parts of the front-line, German soldiers initiated a cease-fire through song. On Christmas Day the guns were silent and there were several examples of soldiers leaving their trenches and exchanging gifts. The men even played a game of football.

In January 1916, Asquith was asked to work as defence counsel to Ian Colquhoun who was being court-martialled for "allowing his men to fraternise with the Germans on Christmas Day". Raymond was impressed by Colquhoun "for the vigour and nerve with which he faced his accusers" and in his "insolence, aplomb, courage and elegant virility". Despite his efforts, Colquhoun was convicted but escaped with a reprimand.

Raymond Asquith resisted attempts by his father to use his influence to transfer him onto the General Staff but against his wishes he did serve for four months (January to May 1916) at general headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force, at Saint-Omer, where he "served unenthusiastically in intelligence work".

During this period he became greatly concerned about the influence of Lord Northcliffe and his newspapers, The Times and The Daily Mail. There were constant criticism of Asquith, especially over the reluctance of accepting the need of conscription (compulsory enrollment). "Raymond was an indignant as anyone, telling Katherine Asquith that he had reached the stage when he would rather defeat Northcliffe than defeat the Germans. The press lord seemed to him just as belligerently crass and crassly belligerent as the enemy were, but far less courageous and capable".

Raymond Asquith returned to the Western Front on 16th May 1916. He became increasingly critical of the way the war was being fought. He told his wife that "almost every night there were raids on the German lines accompanied by the usual ridiculous artillery barrage" and he "considered the whole business to be a charade, usually causing far more British than German casualties".

On 7th September, 1916, Asquith visited the front-line and managed to obtain a meeting with his son. He wrote to Margot Asquith that evening: "He was very well and in good spirits. Our guns were firing all round and just as we were walking to the top of the little hill to visit the wonderful dug-out, a German shell came whizzing over our heads and fell a little way beyond... We went in all haste to the dug-out - 3 storeys underground with ventilating pipes electric light and all sorts of conveniences, made by the Germans. Here we found Generals Horne and Walls (who have done the lion's share of all the fighting): also Bongie's brother who is on Walls's staff. They were rather disturbed about the shell, as the Germans rarely pay them such attention, and told us to stay with them underground for a time. One or two more shells came, but no harm was done. The two generals are splendid fellows and we had a very interesting time with them."

On 15th September, Raymond Asquith led his men on a attack on the German trenches at Lesboeufs. According to one of his men "such coolness under shell fire as he displayed would be difficult to equal". Soon after leaving the trench he was hit in the chest by a bullet. Raymond knew straightaway that his wound was fatal, but in order to reassure his men, he casually lit a cigarette as he was carried on a stretcher to the dressing station. A medical orderly wrote to his father to say he was not given morphia "as he was quite free from pain and just dying."

Raymond Asquith died on the way to the dressing station. According to a soldier quoted by John Jolliffe: "There is not one of us who would not have changed places with him if we had thought that he would have lived, for he was one of the finest men who ever wore the King's uniform, and he did not know what fear was." Only five of the twenty-two officers in Asquith's battalion survived the battle unscathed.

When his father was informed of his death "he put his head on his arms on the table and sobbed passionately". He told Margot Asquith: "The awful waste of a man like Raymond - the best brain of his age in our time - any career he liked lying in front of him. I always felt it would happen." Two days later he wrote to Sylvia Henley: "I can honestly say, that in my own life he was the thing of which I was truly proud, and in him and his future I had invested all my stock of hope."

On this day in 1919 businessman Andrew Carnegie died. By the time he had died he had given away $350,000,000. A further $125 million was placed with the Carnegie Corporation to carry on his good works.

Andrew Carnegie, the son of a handloom weaver, was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, on 25th November, 1835. The family had a long radical tradition and his father, William Carnegie, was an active Chartist. His material grandfather, Thomas Morrison, had worked with William Cobbett during his campaign for social reform.

The economic depression of 1848 convinced the Carnegie family to emigrate to the United States where they joined a Scottish colony at Allegheny near Pittsburgh. Andrew began work at 12 in a local cotton factory but continued his education by attending night school.

At 14 Carnegie became a messenger boy in the local Pittsburgh Telegraph Office. His abilities were noticed by Thomas A. Scott, the superintendent of the western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. He made Carnegie his secretary. During the Civil War Scott was appointed assistant secretary of war and Carnegie went to Washington to work as his right-hand man. Carnegie's work included organizing the military telegraph system.

After the war Carnegie succeeded Scott as superintendent of the western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Carnegie shrewdly invested in several promising ventures including the Woodruff Sleeping Car Company and several small iron mills and factories. The most important of these was Keystone Bridge, a company which he owned a one-fifth share.

Carnegie made regular visits to Britain where he observed the rapid developments in the iron industry. He was especially impressed by the converter invented by Henry Bessemer. Carnegie realised that steel would now replace iron for the manufacture of heavy goods.

In 1870 Carnegie erected his first blast furnace where he used the ideas being developed by Bessemer in England. Others followed and by 1874 he opened his steel furnace at Braddock. He took several partners, including Henry Frick, but he always insisted in retaining the majority holding in his various ventures.

Carnegie took a keen interest in social and political issues and wrote a series of books including Round the World (1881), An American Four-in-Hand in Britain (1883) and Triumphant Democracy (1886), where he compared the egalitarianism of America with the class-based inequalities of Britain and other European countries. He praised America's educational system arguing that: "Of all its boasts, of all its triumphs, this is at once its proudest and its best."

In June, 1889, the North American Review published an article by Carnegie on what he called the "Gospel of Wealth". In the article Carnegie argued that it was the duty of rich men and women to use their wealth to benefit the welfare of the community. He wrote that a "man who dies rich dies disgraced".

In 1889 Carnegie decided to allow Henry Frick to become chairman of the Carnegie Companywhile he moved to New York to deal with the growing importance of research and development. Carnegie also spent six months of the year in Scotland with his family.

When Frick took control the firm consisted of various mills and furnaces in the Pittsburgh area. Frick was concerned that there was no centralized management structure and so in 1892 all productive units were integrated to form the Carnegie Steel Company. Valued at $25 million it was now the largest steel company in the world.

In an effort to increase profits, Henry Frick decided to lower the piecework wage rate of his employees. In 1892 the Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers Union called out its members at the Carnegie's Homestead plant. Frick now took the controversial decision to employ 300 strikebreakers from outside the area. The men were brought in on armed barges down the Monongahela River. The strikers were waiting for them and a day long battle took place. Ten men were killed and 60 wounded before the governor obtained order by placing Homestead under martial law.

Carnegie, who was in Scotland during the strike, was furious with Frick as he had instructed him not to use strikebreakers. In public Carnegie did not criticize Frick and as a result had to take responsibility for what had happened. He later wrote: "I was the controlling owner. That was sufficient to make my name a by-word for years".

The Carnegie Steel Company continued to expand and between 1889 and 1899 annual production of steel rose from 332,111 to 2,663,412 tons, and profits increased from $2 million to $40 million. There was growing conflict between Carnegie and Henry Frick during this period. This came to a head in 1899 and Carnegie bought out Frick for $15 million.

In 1901 Frick joined with J. Pierpont Morgan to purchase the Carnegie Company for $500,000,000 and established the U.S. Steel Corporation that was valued at $1.4 billion. Carnegie himself now had a personal fortune of $225,000,000.

Carnegie set up a trust fund "for the improvement of mankind." This included the building of 3,000 public libraries (380 in Britain), the Carnegie Institute of Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Institute of Technology and the Carnegie Institution of Washington for research into the natural and physical sciences. Carnegie also established the Endowment for International Peace in an effort to prevent future wars.