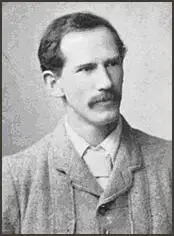

Cecil Reddie

Cecil Reddie, the sixth of ten children of James Reddie, Admiralty civil servant and his wife, Caroline Susannah, was born on 10th October 1858 in Colehill Lodge, Fulham, London. (1)

Reddie spent four years as a day boy at Godolphin School, but after his parents' death and the children's dispersal throughout Britain he was a day pupil at Birkenhead School (1871–2) and a boarder at Fettes College (1872-1878).

This was followed by Edinburgh University, in 1878–82. Reddie read in succession medicine and science, and after two years at Göttingen University took a doctorate in chemistry in 1884. (2)

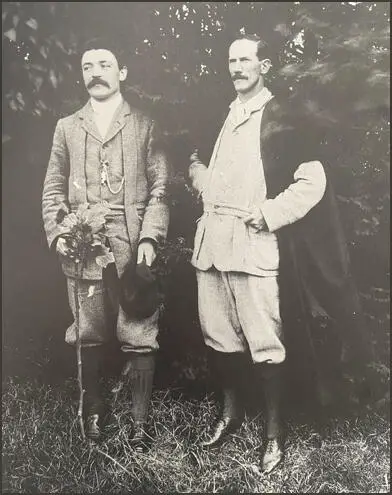

Reddie returned to Fettes College to teach science, moving thence to Clifton College in April 1887. During this period he met Edward Carpenter. (3) Influenced by the work of John Ruskin, Carpenter began to develop ideas about a utopian future that took the form of a kind of primitive communism. By the 1880s Carpenter had established himself as a poet of democracy and socialism with books like Towards Democracy (1883). He was also a member of the Social Democratic Federation. (4)

According to his biographer, Peter Searby, Reddie was introduced to the socialist ideas of John Ruskin and William Morris. "As a pupil he was bored by the classical curriculum and by competitive games; agonizing over his homosexual nature, he craved emotional guidance. Ideas for school reform came to him as a young teacher, his mentors including his Fettes colleague Clement Charles Cotterill, the Scottish polymath Patrick Geddes, and the romantic socialist Edward Carpenter. They were Ruskinians, and Abbotsholme was inspired by Ruskin's disdain for the competitive society, and his wish to replace undue bookishness with 'learning by doing' so as to foster co-operativeness." (5)

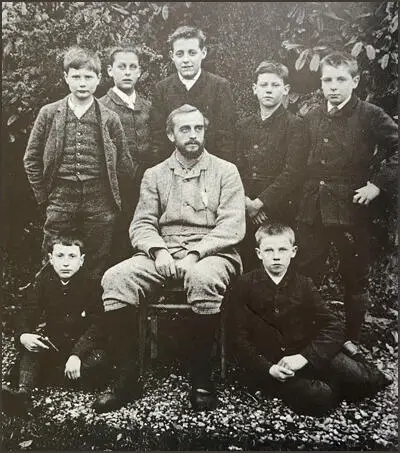

Abbotsholme School

After a mental breakdown Reddie left Clifton College and went to live with Edward Carpenter and his lover, Albert Fearnhough. Carpenter suggested that Reddie started up a new school which would "create a new man". (6) It was while living with Carpenter, Reddie met Robert Muirhead: "I met Dr Cecil Reddie and a project was mooted to start a new school on more or less Socialist lines with Reddie as head master and with the co-operation of Carpenter and myself and possibly others. It was not till after a year or two's incubation that this project actually materialised. At one stage it was contemplated that a site in Yorkshire within easy reach of Millthorpe should be chosen, and that the new school should be run by four partners, Dr Reddie, Carpenter, William Cassels, and myself, Carpenter giving part time and the three others their whole time to the work of the school." (7) Carpenter offered to teach boxing at the school, adding, "I don't advise you to undertake it unless you like organisation (I hate it). (8)

Carpenter told his friend, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, about the proposed school. Dickinson knew that his friend from university, John Haden Badley, was interested in progressive education. He sent him a letter suggesting he should meet Cecil Reddie, who was planning to establish a new school, Abbotsholme, near the village of Rocester. Badley returned to England and after an interview he accepted the offer of a job at the school. (9)

Badley explained in a letter to his mother his decision to teach at Abbotsholme: "The fact is, that I have had an offer of work in the autumn, and one which I am very eager to accept. My last summer's experience has shown me that I can hardly hope for congenial work at a great public school: and that to work successfully and happily I want more freedom of action than one is allowed there. Some of my friends began to laugh, and say I must wait till an ideal school was founded, which seemed a somewhat hopeless prospect: but while I am waiting, a school just after my own heart is being founded, and in the strangest manner I am asked to join." (10)

Badley's father wanted him to become a barrister. He therefore had to explain why he was determined to become a schoolteacher: "If teaching is to be my work, I think it must be, or must begin, in some such a way as this.... I have the ambition to do what I can in the fullest way, and of trying to live and teach others to live in what I believe to be the best way. I am aware that will sound presumptuous on my part: but if I am so young as to believe that some things may be changed for the better I am also young enough to be eager to do all I can.... perhaps I shall grow wiser in time; at least I am willing to buy the experience and pay the full price for it." (11)

Abbotsholme School began on 1st October 1889 with sixteen pupils. Reddie only had two members of staff, John Haden Badley and Robert Muirhead. William Cassels, who had invested money in the project, ran the farm attached to the school. (12) Reddie stressed practical work on the school estate. Although Reddie was a very directive headmaster, pupils were given unusual freedom to roam the countryside. "Progressive parents were attracted by its ingenious combination of Ruskinian 'helpfulness' with public-school authoritarianism, its sympathetic atmosphere and sensitive sex instruction, its eclectic Christianity with chapel readings from Confucius and Emerson, its Jaeger uniform, and its cult of fresh air." (13)

Badley taught History and French while Muirhead taught mathematics. Reddie, who spoke the language fluently, would teach German. It has been pointed out: "The preoccupation with diet, correct clothing, a balance between work in the classroom and on the farm and estate, the insistence on the dignity of manual labour, and of learning to use one's hands in craftsmanship, must have struck Badley as a complete revelation." (14)

John Hadyn Badley

At first John Haden Badley enjoyed teaching at Abbotsholme: "It was a happy and strenuous time, for our hearts were in the work; first of all the necessary preparation and then, when term began, that of getting the classes started and the manifold open-air activities in which we all took part. It was a many-sided life in which all one's powers were being used for things that every member of the community, old and young alike, felt to be worth doing; and the atmosphere of comradeship in all we did gave a sense of underlying satisfaction that was soon as much a part of our life as the beauty of woodland and river and hills before our eyes." (15)

According to J H G I Giesbers: "Very soon disagreement and friction developed within the triumvirate. Muirhead and Cassels had been mainly interested in the New School because they considered it an experiment in practical Socialism, a model agricultural community on the lines of the Fellowship of the New Life. While drawing up the first prospectus, however, they discovered to their dismay that Reddie's intentions were quite different; he wanted a school which catered for the Directing Classes, a school for rulers. By the time that he had become headmaster of Abbotsholme, his early Socialism had cooled down considerably, while theirs was as ardent as ever. Besides, Muirhead and Cassels resented Reddie's high-handed treatment and autocratic ways." (16)

Robert Muirhead later explained what happened: "There the new School started in 1889. The lines on which it started were no doubt due to the very definite ideas of Dr Reddie on school education, and were somewhat different from what Carpenter had in mind, and partly on this account and partly because the site chosen was not quite near to Millthorpe, Edward Carpenter did not enter the partnership but remained as adviser and occasional visitor, a strong supporter of the School.... Towards the end of the first year, however, differences arose between Dr Reddie and Mr Cassels, which seemed to make it impossible for them to continue co-operation. I took the view that the blame for this rested on Dr Reddie, and after some consultation with Edward Carpenter, Cassels and I decided to break up the partnership. Thereupon it was arranged that Cassels and I should leave at the end of the term and allow Dr Reddie to carry on the School on his own lines." (17)

John Haden Badley married Amy Garrett on 8th November 1892, at Gengenbach, Baden, Germany. (18) John and Amy began talking about setting up their own progressive school. Badley found Cecil Reddie a difficult man to work with. Although he shared Reddie's educational philosophy, that included "dismissing the classics, arguing for the study of modern societies, envisaging inter-disciplinary links between history and geography" as well as being "a firm believer in craft education and manual work", he disagreed with his autocratic style of leadership. Edward Carpenter, who had helped fund the venture, shared Badley's concerns. (19) So did fellow member of staff, Robert Muirhead, who told John Bruce Glasier that Reddie's manner had "turned the whole project sour for him." (20)

Badley commented that: "Reddie taught me everything I needed to do and what not to do". Although he admitted that it was "Reddie who helped him to discover what he wanted to do in education. He spoke later of having been apprenticed to a master craftsman." (21) Reddie, who was an homosexual "disliked the company of women" and "women were seen as servants in the kitchens". He also disapproved of Badley's marriage and so he felt he had to leave Abbotsholme School. (22)

John and Amy Badley opened the school in a rented house called Bedales at Lindfield, near Haywards Heath, in January 1893 in partnership with fellow teacher Oswald Byrom Powell (1867-1967), and his wife Winifred Cobb Powell (1861-1937). John later wrote to Oswald: "People ought always to speak of it as our work (yours and Winifred's as much as Amy's and mine)." (23)

German Influence

In 1893 Abbotsholme had 47 pupils. In March 1894, through the generous assistance of a friend, Reddie bought the school and estate for £12,500. From this moment Abbotsholme was Reddie's private property. "The 14th of March 1894 was henceforward considered as the second foundation of the school and the identification of Reddie and Abbotsholme became complete." (24)

A significant number of the sixty pupils present at Abbotsholme in 1900 came from continental Europe. Abbotsholme was a model for similar foundations in France and Germany. Yet growth was discouraged by the lack of concern for specialist teaching and external examinations. He saw the German state as the model that Britain should follow to defeat commercial competition. He also abandoned his socialist beliefs became openly authoritarian. (25) He became close friends with Herman Lietz, who took Reddie's ideas to Germany. (26)

Conflict with Staff

Cecil Reddie saw his school as a great success. He decided to expand the school by commissioning new buildings. A new south-west wing with dining-room, kitchen, chapel, dormitory, sickrooms and spare bedrooms was officially opened in 1900. However, this rebuilding caused conflict with the staff. (27)

Stanley Unwin, a former head boy had just joined the staff: "There is no doubt that the building operations were a terrible strain both upon C.R. himself and certain of his staff, to which C.R. himself contributed not a little by his idiotic refusal to speak to the foreman builder and his insistence upon dealing with the smallest query by correspondence. Every detail was taken with tragic seriousness, and even we boys could see that headmaster and staff were much on edge. But we did not foresee that by the last week of term, C.R. and one of his staff would be completely unbalanced mentally, with disastrous results for the school." (28)

At that time Reddie's staff included Frank Ellis (English, Latin, Greek, history, physics and mathematics), George Hooper (English, geometry, drawing and painting), Sidney Unwin (natural sciences, horticulture, veterinary hygiene, surveying) and Dr. J. G. Van Eyck had been Professor of Public Law in Batavia but taught a variety of different subjects at Abbotsholme. Reddie accused "Van Eyck, Ellis, Hooper and Unwin, the dissentient masters, whom he accuses of seeking self-advancement, fame and material reward." (29)

One parent complained: "You are very gentle, kind and sympathetic on the surface, but you are possessed of a will of adamant underneath, and what these men feel is that they have got no scope to do things their own way, you cut them short when they come with their suggestions and they go away with a feeling of sickness of heart. You give too much time to details and overwhelm yourself with work in this manner, instead of detailing it to others." (30)

Stanley Unwin wrote in his diary: "Everything was sacrificed to the Building.... To think such devotion, such love as existed 3 years ago, before those damned buildings, should have ended in this! Cause of it all! Reddie's pride. He never says: I'm wrong. I see you are right. I'm sorry. He wants to concentrate everything round himself, and thus prevents anyone else having, or taking any responsibility or showing initiative. He complains of want of co-operation, but won't co-operate himself. He won't trust people... He has no consideration for others, where his whims are concerned. He allows himself to say: It is my right to be cantankerous... In 1900 he was Egoist, conceited, selfish, inconsiderate, intolerant and cantankerous - just a driver - never admitting himself wrong but looking about to see how he could put the blame on somebody else. He found it difficult to judge anything on its own merits, but always looked first to find some bad motive behind. If it was possible for a wrong interpretation to be put on anything he was the man to do it. He concentrated everything in his own hands and wasted hours over petty details, and then talked about his work as 'a miracle of organisation,' while he made true co-operation impossible. The hitch that caused the delay was C.R. himself. He could do no wrong! and he refused to speak and wrote letters instead. What could have been settled in a minute, took hours. He could trust no one - not even his dearest friends who had been loyal to him for years." (31)

First World War

The building dispute resulted in three teachers and thirteen boys leaving the school. By 1914 Abbotsholme only had 31 pupils. After the outbreak of the First World War it fell to 22. J H G I Giesbers pointed out: "Reddie's dream of an intellectual and cultural alliance between Britain and Germany was cruelly disturbed. His ideal had always been to bring together in the New School Movement Britain's best qualities such as self-reliance, individual initiative and sportsmanship, with those of Germany, thoroughness, method, industry and discipline... Other problems which confronted Reddie were the provision of food and finding adequate teaching and domestic staff. Between 1916 and 1918 he had many mistresses on his staff which greatly irritated the bachelor-headmaster. Because he always wanted to supervise every detail, the strain rapidly affected him " (32)

The war had an impact on his personality. One of his students pointed out: "Always a complex combination of devil and saint, the devil now took command. His temper was ungovernable. He shouted, stormed and raged. He seldom came into class without a cane. Teaching, what there was of it, was thrown completely to the winds, and instead we suffered tirades against the English, against women and against Public Schools. Only Germany was extolled although at that very time German bullets were tearing Old Abbotsholmians to death. His classes became reigns of terror, and rested like a dead weight upon the happiness of the boys. Even bathing was spoilt, with C.R. always present, shouting at us to do this and that.. The freedom and gaiety of the school completely disappeared. Instead there was oppression and failure. Each term more boys left." (33)

Despite his pro-German views his previous students were very keen to serve during the First World War and thirty Abbotsholmians and one former teacher were killed on the Allied side and an unknown number of its foreign pupils on the enemy side. Cecil Reddie's favourite pupil, whom he had marked out as his successor, Captain Roderick Bemrose, was killed four days before the Armistice was signed. (34)

Reddie explained his feelings for Bemrose in a sermon he gave on 25th November, 1918: "I cannot disguise that the personal loss to me has been simply overwhelming... I cannot pretend to remember exactly when I first heard from his father that he wished to be a school-master... but I was filled with great joy when I heard that, because one of the things that had weighed me down for years has been the terrible fear that I should find nobody to carry on this place... of all the boys that have been here, this was the boy that seemed to me most able to carry it on... I did not put it into his head, I did not dangle any sort of expectation about it, but, when I heard from his home that that was his hope, to be a schoolmaster, I must say that then I began to put all my hope in his life, this precious life.... No one can look into the future and see what is going to happen, but I can only tell you this, that I see no signs in this country of people taking up education in the right manner... it will be a very sad thing for me and this place I think, if it fell into the hands of any ordinary type who would contrive as soon as possible to obliterate all signs of our work here... At present I am simply stunned by this loss. I do not know what will be the result of this... It was very natural to put one's hope on that boy. He was so very suitable in so many ways." (35)

Retirement

At the end of the war Abbotsholme School only had 20 pupils. Although sixty years old with incredible energy, resilience and tenacity he set to work and within two years he had practically doubled the number of boys. By 1920 it had 47 pupils but this growth did not continue and in 1921 it had fallen to 28. This caused a financial crisis for Reddie and he had to look for new investors. (36)

Cecil Reddie pointed out in a sermon on 6th October 1924. "I presume it must be palpable to everyone that the school is not in what might be called a flourishing condition... even if we had the most excellent programme here, what are we to do when the great thing is to pass examinations? In the words of our most distinguished chemist, Sir William Ramsay: 'the more examinations passed, the greater the fool produced'. When it comes to examinations the parents merely look at the list to see if their boy has placated some ridiculous person in some examination... the question for us all is whether we are going to fight for something worth having or whether we are merely going in for popular applause... if I want to full this place I have only to use the customary phrases, but i do not want success on such terms, I am to find out what the Englishman is like, to see how far he is worth preserving, and how far he can be improved, I care nothing for what the result may be, if we cannot get that, it is not worth while troubling about anything else." (37)

In 1926 Abbotsholme School only had eight pupils. Cecil Reddie explained his problems in a letter to old boy, Lytton Strachey: "Please excuse brevity and any faults of expression. The matter is most urgent and I am very tired. I am 68 and my strength has begun to give way, so that I desire to be relieved of my heavy burden lest I should suddenly collapse... As I am dead beat, I am anxious to settle the future of the school forthwith... Quite apart from the state of England I ought to provide for the future of the school as soon as possible, for, in case of my death the death-duties would be about £5,000... I have no means of livelihood apart from the school, as all my family property and all the earnings of the school have gone to build up the place. As I cannot work much longer, I must either sell the place or transfer it to others... Altogether I have spent on it about £50,000. If it could be transferred to a private limited company of Old Boys and Friends, the school could be carried on in the old way, and the Old Boys would have the satisfaction of preserving their old house. I am willing to hand it over to such a company in return for a sum of money sufficient for my modest needs. I am advised that, considering my age and the possibility of ill-health, and medical and nursing expenses, I ought to have at least £750 a year. I cannot expect to live many years and I do not think the sum named extravagant." (38)

The letter was passed to the Abbotsholme Association who agreed to help. £6,000 was offered on condition that the management of the school should be transferred to a council of Old Boys. In October 1926, after difficult and almost endless negotiations Reddie appointed a Provisional Council of fifteen members, and in November an Executive Council of five. The Old Boys persuaded Reddie to meet Colin Sharp, Reader in English at St. Stephen's College, Delhi; the first meeting took place in August 1926, the second in January 1927. According to Sharp: "Abbotsholme School then consisted of Dr. Reddie himself, Miss Gifford, his secretary, Miss Ryell, the Matron, a housemaid, a kitchen maid, a boot boy, a gardener and a boy, a bailiff and boy on the farm, no teaching staff, and two boys only in the school, one at first away with a cold. Dr. Reddie, ill, brokenhearted, but full of pluck, most charming in his speech, but bitter towards the world that had not recognized and accepted his message, impressed me as an outstanding and delightful man. Nightly he never stopped talking from 6 p.m. to 2 a.m.; but when not riding his particular hobbies of Moshe (Jews), sex, the inferiority of women, and the putrid English character." (39)

Now with only two pupils and facing bankruptcy, Reddie decided he had no option but to leave the school. In March 1927 Reddie accepted Colin Sharp as his successor. A private limited company of Old Abbotsholmians was formed to take over the school. The terms of transfer were a cash payment of £5,500 and an annuity of £400. The only condition was, "not to stay on in the school, but be welcome for occasional visits." (40)

Reddie retired to 1 High Oaks Road, Welwyn Garden City. He invited Old Abbotsholmians to join him on long walks and cycling-tours. In the evenings he played on his organ the Gregorian music which he had introduced at Abbotsholme. He began work on his memoirs but progress was very slow. At the beginning of 1932 he wrote in his diary: "CR. must seriously settle down to his memoirs this year." (41)

In January 1932 he fell ill. He was operated on but complications set in and he died in St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, on 6th February 1932. He was buried in the grounds of Abbotsholme. (42)

Primary Sources

(1) John Haden Badley, Memories and Reflections (1955) page 107

It was a happy and strenuous time, for our hearts were in the work; first of all the necessary preparation and then, when term began, that of getting the classes started and the manifold open-air activities in which we all took part. It was a many-sided life in which all one's powers were being used for things that every member of the community, old and young alike, felt to be worth doing; and the atmosphere of comradeship in all we did gave a sense of underlying satisfaction that was soon as much a part of our life as the beauty of woodland and river and hills before our eyes.

(2) J H G I Giesbers, Cecil Reddie and Abbotsholme: A Forgotten Pioneer and His Creation (1979)

Very soon disagreement and friction developed within the triumvirate. Muirhead and Cassels had been mainly interested in the New School because they considered it an experiment in practical Socialism, a model agricultural community on the lines of the Fellowship of the New Life. While drawing up the first prospectus, however, they discovered to their dismay that Reddie's intentions were quite different; he wanted a school which catered for the Directing Classes, a school for rulers. By the time that he had become headmaster of Abbotsholme, his early Socialism had cooled down considerably, while theirs was as ardent as ever. Besides, Muirhead and Cassels resented Reddie's high-handed treatment and autocratic ways. In the course of the first term signs of a growing rift became frequent and before Christmas things had come to a head.

Cassels resigned his post, Muirhead stayed till the end of the second term. By Christmas 1889 Reddie was sole master of Abbotsholme. In the thirty-eight years of his headship he consistently refused government by committee, which may be considered one of the reasons why eventually he failed.

When Abbotsholme started, there were only 16 pupils. Reddie aimed at 100 because he feared that too great a school-population would destroy the necessary unity. During his reign the school never reached the 100-mark and as the following figures indicate, the numbers of boys fluctuated very much: 1893 - 47; 1899 - 60; 1912 - 34; 1914 - 31; autumn 1914 - 22; 1917 - 13; 1918 - 20; 1919 - 22; autumn 1919 - 44; 1920 - 47; 1921 - 28; 1926 - 8; in 1927, when Reddie resigned, there were only 2 pupils left.

(3) Stanley Unwin, The Truth about a Publisher (1960)

There is no doubt that the building operations were a terrible strain both upon C.R. himself and certain of his staff, to which C.R. himself contributed not a little by his idiotic refusal to speak to the foreman builder and his insistence upon dealing with the smallest query by correspondence. Every detail was taken with tragic seriousness, and even we boys could see that headmaster and staff were much "on edge." But we did not foresee that by the last week of term, C.R. and one of his staff would be completely unbalanced mentally, with disastrous results for the school."

(4) Stanley Unwin, diary entry (17th November 1900)

I have reached a crisis in my life. What may happen in the next few months God alone knows. I will try once more to get Dr. R. to see what the state of mind of his staff is due to. If he changes, well and good. If not, then goodbye Abbotsholme .. . He poor fellow, says life is unendurable here. (Hooper): "What we want here is a new spirit - to go back to 96 and 97, to be treated with more confidence, to be allowed more freedom for individual initiative... The spirit among the fellows has changed. They've lost their ideals. It is a different place to what it was... Everything was sacrificed to the Building. No one's individuality was considered... Look at those notices to the staff - so potty - discussing all the different ways of spelling "Head Master" and "Your's truly". Such trifles when great principles are at stake. This place was once a home."... To think such devotion, such love as existed 3 years ago, before those damned buildings, should have ended in this! Cause of it all! Reddie's pride. He never says: I'm wrong. I see you are right. I'm sorry. He wants to concentrate everything round himself, and thus prevents anyone else having, or taking any responsibility or showing initiative. He complains of want of co-operation, but won't co-operate himself. He won't trust people. He kills out in his staff all love. He has no consideration for others, where his whims are concerned. He allows himself to say: It is my right to be cantankerous.

C.R. in 1889 was an idealist, he was humble, unselfish (jealous even then and suspicious) but a leader of men and a lover of boys - the most Christ like man I have ever met. In 1900 he was Egoist, conceited, selfish, inconsiderate, intolerant and cantankerous - just a driver - never admitting himself wrong but looking about to see how he could put the blame on somebody else. He found it difficult to judge anything on its own merits, but always looked first to find some bad motive behind. If it was possible for a wrong interpretation to be put on anything he was the man to do it. He concentrated everything in his own hands and wasted hours over petty details, and then talked about his work as "a miracle of organisation," while he made true co-operation impossible. The hitch that caused the delay was C.R. himself. He could do no wrong! and he refused to speak and wrote letters instead. What could have been settled in a minute, took hours. He could trust no one - not even his dearest friends who had been loyal to him for years.

(5) G. Dixon, Fifty Years of Abbotsholme (1939) page 38

Always a complex combination of devil and saint, the devil now took command. His temper was ungovernable. He shouted, stormed and raged. He seldom came into class without a cane. Teaching, what there was of it, was thrown completely to the winds, and instead we suffered tirades against the English, against women and against Public Schools. Only Germany was extolled although at that very time German bullets were tearing Old Abbotsholmians to death. His classes became reigns of terror, and rested like a dead weight upon the happiness of the boys. Even bathing was spoilt, with C.R. always present, shouting at us to do this and that.. . The freedom and gaiety of the school completely disappeared. Instead there was oppression and failure. Each term more boys left.

(6) G. Peach, Fifty Years of Abbotsholme (1939) page 40

CR. seemed totally unable to get on with any of them. They consisted of two main types - those who wanted to build up a new educational system based on complete freedom of expression and those who must needs drown their war memories in drink. C.R. quarrelled violently with the former and sacked the latter. It was only from the women teachers of whom there were one or two during this period that I learned anything. I think it was largely due to these difficulties that the revival in the school's fortune was so short-lived.

(7) Cecil Reddie, sermon following the death of Captain Roderick Bemrose (25th November 1918)

I cannot disguise that the personal loss to me has been simply overwhelming... I cannot pretend to remember exactly when I first heard from his father that he wished to be a school-master... but I was filled with great joy when I heard that, because one of the things that had weighed me down for years has been the terrible fear that I should find nobody to carry on this place... of all the boys that have been here, this was the boy that seemed to me most able to carry it on... I did not put it into his head, I did not dangle any sort of expectation about it, but, when I heard from his home that that was his hope, to be a schoolmaster, I must say that then I began to put all my hope in his life, this precious life. For the last few years that he was here, he was my confident in all... It is not possible, in the time left, to be able to bring up and train any boy to carry on this place, and therefore to me it seems as if the natural heir, the hope of this school had perished with that life. No one can look into the future and see what is going to happen, but I can only tell you this, that I see no signs in this country of people taking up education in the right manner... it will be a very sad thing for me and this place I think, if it fell into the hands of any ordinary type who would contrive as soon as possible to obliterate all signs of our work here... At present I am simply stunned by this loss. I do not know what will be the result of this... It was very natural to put one's hope on that boy. He was so very suitable in so many ways.

(8) J H G I Giesbers, Cecil Reddie and Abbotsholme: A Forgotten Pioneer and His Creation (1979)

In August 1914 Reddie's dream of an intellectual and cultural alliance between Britain and Germany was cruelly disturbed. His ideal had always been to bring together in the New School Movement Britain's best qualities such as self-reliance, individual initiative and sportsmanship, with those of Germany, thoroughness, method, industry and discipline. Four long war-years would be a formidable obstacle to the realisation of this ideal. Because of the relatively large number of foreign pupils, Abbotsholme was very vulnerable. The young foreigners left immediately and numbers dropped from 39 in the summer of 1914 to 22 in autumn. Besides, English boys left school for the Army approximately two years earlier than in peace-time. In 1918 Abbotsholme had no more than 20 pupils.

Other problems which confronted Reddie were the provision of food and finding adequate teaching and domestic staff. Between 1916 and 1918 he had many mistresses on his staff which greatly irritated the bachelor-headmaster. Because he always wanted to supervise every detail, the strain rapidly affected him...

When in 1918 the Armistice was signed, Reddie was tired, bitter, disappointed, broken. The nineteenth of July 1919 was a national holiday in Britain but not at Abbotsholme. "This school which is out for National reconstruction, has nothing to do with that cesspit and madhouse England."

Thirty Abbotsholmians and one master were killed on the Allied side and an unknown number of its foreign pupils on the enemy side. A very great personal tragedy was that Reddie's favourite pupil, whom he had marked out as his successor, Captain Roderick Bemrose, was killed four days before the Armistice was signed.

(9) Cecil Reddie, letter to Lytton Strachey (July, 1926)

Please excuse brevity and any faults of expression. The matter is most urgent and I am very tired. I am 68 and my strength has begun to give way, so that I desire to be relieved of my heavy burden lest I should suddenly collapse... As I am dead beat, I am anxious to settle the future of the school forthwith... Quite apart from the state of England I ought to provide for the future of the school as soon as possible, for, in case of my death the death-duties would be about £5,000... I have no means of livelihood apart from the school, as all my family property and all the earnings of the school have gone to build up the place. As I cannot work much longer, I must either sell the place or transfer it to others... Altogether I have spent on it about £50,000. If it could be transferred to a private limited company of Old Boys and Friends, the school could be carried on in the old way, and the Old Boys would have the satisfaction of preserving their old house. I am willing to hand it over to such a company in return for a sum of money sufficient for my modest needs. I am advised that, considering my age and the possibility of ill-health, and medical and nursing expenses, I ought to have at least £750 a year. I cannot expect to live many years and I do not think the sum named extravagant. Anyhow, I am willing to accept it and make the best of it. But, as it is impossible to rent a house, I must buy one (for, say, £2,000); and I wish to have a lump in addition, so that I can publish my memoirs, finish the Abbotsholme psalter and liturgy, etc. and leave the legacies to those that will be looking after me at the end. My residue I wish to come back to the school as an endowment. It is proposed therefore that half the pension, £350, should be provided by a lump sum of £7,500, the other £350 coming out of the annual income of the school... I am not asking for money for myself; for, if I sold, I should have more than enough to live on. But I am fighting for the school and for the ideals and methods that have made it famous all over the world. I desire to hand over the whole place and all that it contains, except my private papers, a few books and pictures, and the necessary furniture for my new home... I confidently believe that the sons of Abbotsholme will not let their old home perish.

(10) Cecil Reddie, sermon (6 October 1924)

"I presume it must be palpable to everyone that the school is not in what might be called a flourishing condition... even if we had the most excellent programme here, what are we to do when the great thing is to pass examinations? In the words of our most distinguished chemist, Sir William Ramsay: 'the more examinations passed, the greater the fool produced'. When it comes to examinations the parents merely look at the list to see if their boy has placated some ridiculous person in some examination... the question for us all is whether we are going to fight for something worth having or whether we are merely going in for popular applause... if I want to full this place I have only to use the customary phrases, but i do not want success on such terms, I am to find out what the Englishman is like, to see how far he is worth preserving, and how far he can be improved, I care nothing for what the result may be, if we cannot get that, it is not worth while troubling about anything else.