John Stubbs

John Stubbs, the eldest of three sons and four daughters, was born in Norfolk in about 1542. He was educated at Trinity College. He graduated from Cambridge University on 31st January 1561 and the following year he entered Lincoln Inn. During this period he developed strong Puritan views. According to Natalie Mears he felt particularly strongly on "the eradication of such practices as the wearing of surplices and kneeling at communion". Stubbs was called to the bar on 2nd February 1572. Some time between 1575 and 1579 Stubbs married Anne Vere. (1)

In 1579 Christopher Hatton, a member of the Privy Council and was involved in negotiations about the possible marriage of Queen Elizabeth to the Duke of Alençon. Hatton was against the match "but joined with the rest of the council in a sullen acquiescence, offering to support the match if it pleased her." (2) However, there was a great deal of opposition to the proposed marriage. As Elizabeth Jenkins has pointed out: "The English dislike of foreign rule, which had shown itself strongly on the marriage of Mary Tudor, was now indissolubly connected with a fear of Catholic persecution. The idea of a French Catholic husband for the Queen roused the abhorrence which, in the Puritans, reached almost to frenzy." (3)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

John Stubbs was totally opposed to the marriage and wrote a pamphlet, The Discovery of a Gaping Gulf, criticizing the proposed marriage. It accused certain evil "flatters" and "politics" of espousing the interests of the French court "where Machiavelli is their new testament and atheism their religion". He described the proposed union as a "contrary coupling" and an "immoral union" like that of a cleanly ox with an uncleanly ass". (4) Stubbs accused the Alençon family of suffering from sexually transmitted diseases and that Elizabeth should consult her doctors who would tell her she was exposing herself to a frightful death. (5) Stubbs also argued that, at forty-six, Elizabeth may not have children or may be endangered in childbirth. (6)

On 27th September 1579 a royal proclamation was issued prohibiting the circulation of the book. On 13th October Stubbs, Hugh Singleton (the printer), and William Page (who had been involved in the distribution of the pamphlet) were arrested. Elizabeth wanted to be immediately executed by royal prerogative but eventually agreed to their trial for felony. The jury refused to convict, and they were then charged with conspiring to excite sedition. The use of this statute was criticized by Judge Robert Monson. He was imprisoned and removed from the bench when he refused to retract. (7)

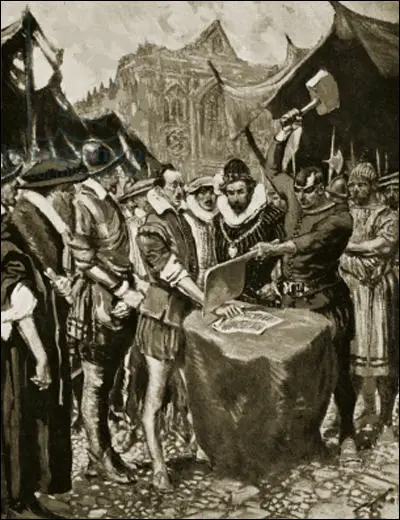

Stubbs, Singleton and Page were all found guilty of sedition and were sentenced to have their right hands cut off and to be imprisoned, though it appears that Singleton was pardoned because of his age: he was about eighty. The sentence was carried out at the market place in Westminster on 3rd November 1579, with surgeons present to prevent them bleeding to death. Stubbs made a speech on the scaffold where he asserted his loyalty and asked the crowd to pray that God would give him strength to endure the punishment.

William Camden points out in The History of Queen Elizabeth (1617): "Stubbs and Page had their right hands cut off with a cleaver, driven through the wrist by the force of a mallet, upon a scaffold in the market-place at Westminster... I remember that Stubbs, after his right hand was cut off, took off his hat with his left, and said with a loud voice, 'God Save the Queen'; the crowd standing about was deeply silent: either out of horror at this new punishment; or else out of sadness." (8)

An eyewitness claims it took three blows before his hand was chopped off. The bleeding was stopped by searing the stump with a hot iron. Stubbs fainted but William Page walked off unaided, and found the strength to shout: "I have left there a true Englishman's hand!" Stubbs and Page were then taken back to the Tower of London. Parliament was due to meet in October, 1579, to discuss her proposed marriage. Elizabeth did not allow this to happen. Instead she called a meeting of her council. After several days of debate the council remained deeply divided, with seven of them against the marriage and five for it. "Elizabeth burst into tears. She had wanted them to arrive at a definite decision in favour of the marriage, but now she was once more lost in uncertainty." (9)

Elizabeth was shocked to discover that the punishment of Stubbs had a negative impact on her popularity. As Anka Muhlstein pointed out: "Thanks to her unerring political instinct, Elizabeth realized at once that she had taken the wrong tack. Her people's respect and affection, which she had never lacked hitherto, were essential to her. The easy-going relationship she enjoyed with her subjects warmed her heart." (10) In January, 1580, Queen Elizabeth admitted to Alençon that public opinion made their marriage impossible.

Stubbs remained in the Tower of London until 1581. The following year, Stubbs's Christian Meditations upon Eight Psalms was printed. In 1585 he became steward of Great Yarmouth and, four years later, its MP. In the House of Commons he sat on four committees (including privileges and the subsidy). (11)

John Stubbs died in February 1590.

Primary Sources

(1) William Camden, The History of Queen Elizabeth (1617)

Stubbs and Page had their right hands cut off with a cleaver, driven through the wrist by the force of a mallet, upon a scaffold in the market-place at Westminster... I remember that Stubbs, after his right hand was cut off, took off his hat with his left, and said with a loud voice, "God Save the Queen"; the crowd standing about was deeply silent: either out of horror at this new punishment; or else out of sadness.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)