Peter Hilton

Peter Hilton, the son of Mortimer Hilton and Elizabeth Freedman, was born on 7th April 1923. His father was a GP in Peckham, London.

According to Martin Childs: "His interest in mathematics was inspired by an unfortunate incident. At the age of 10 he was knocked down by a Rolls-Royce". After many weeks in hospital with his leg in plaster to the waist, he made use of what he later described as "this sort of whiteboard, permanently available to me sitting on my stomach" to solve mathematical problems. (1)

Hilton attended St Paul's School in Hammersmith before winning a scholarship to Queen's College, Oxford, where he read mathematics. However, he was anxious to become involved in the Second World War and in 1941, when he was 18, Hilton was recruited by the Foreign Office on the strength of his mathematical ability and knowledge of German. (2)

Hilton later recalled: "I was recruited by a team looking for a mathematician with a knowledge of German... My knowledge of German was what I had taught myself in one year so I wasn't what they were looking for at all really. But I was the only person who turned up at the interview and they jumped at me and said: 'Yes, you must come.' So I had no right really in a sense to have this job." Hilton was sent to Government Code and Cypher School based at Bletchley Park. (3)

Bletchley Park

Hilton arrived at Bletchley in January, 1942 and initially worked with Alan Turing in Hut 8 on breaking German naval codes produced by Enigma machines. Hilton later recalled: "Alan Turing was unique. What you realize when you get to know a genius well is that there is all the difference between a very intelligent person and a genius. With very intelligent people, you talk to them, they come out with an idea, and you say to yourself, if not to them, I could have had that idea. You never had that feeling with Turing at all. He constantly surprised you with the originality of his thinking. It was marvellous." (4)

At the end of 1942 Hilton went to work with Max Newman, who had been given the problem of dealing with the Lorenz SZ40 machine that was used to encrypt communications between Adolf Hitler and his generals. (5) It operated in a similar way to the Enigma, but the Lorenz was far more complicated, and it provided the Bletchley codebreakers with an even greater challenge. In 1943 Newman came up with a way to mechanise the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher and therefore to speed up the search for wheel settings. (6)

Tommy Flowers, a young telephone engineer, was also involved in the project. He explained the objective of Newman's machine: "The purpose was to find out what the positions of the code wheels were at the beginning of the message and it did that by trying all the possible combinations and there were billions of them. It tried all the combinations, which processing at 5,000 characters a second could be done in about half an hour. So then having found the starting positions of the cipher wheels you could decode the message." (7)

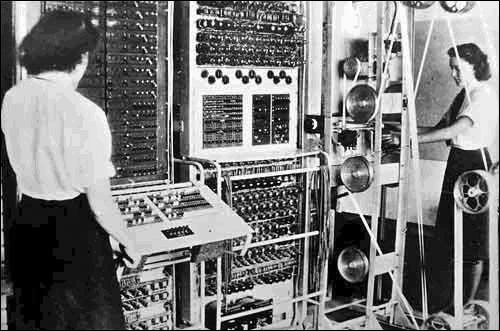

Flowers took Newman's blueprint and spent ten months turning it into the Colossus Computer, which he delivered to Bletchley Park on 8th December 1943, but was not fully operational until 5th February 1944. It consisted of 1,500 electronic valves, which were considerably faster than the relay switches used in Turing's machine. However, as Simon Singh, the author of The Code Book: The Secret History of Codes & Code-Breaking (2000) has pointed out than "more important than Colossus's speed was the fact that it was programmable. It was this fact that made Colossus the precursor to the modern digital computer." (8)

Newman's staff that operated the Colossus consisted of about twenty cryptanalysts, about six engineers, and 273 Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Jack Good was one of the cryptanalysts working under Newman: "The machine was programmed largely by plugboards. It read the tape at 5,000 characters per second... The first Colossus had 1,500 valves, which was probably far more than for any electronic machine previously used for any purpose. This was one reason why many people did not expect Colossus to work. But it began producing results also immediately. Most of the failures of valves were caused by switching the machine on and off." (9)

Peter Hilton believed that Max Newman was an outstanding leader of men: "He realised that he could get the best out of us by trusting to our own good intentions and our strong motivation and he made the thing always as informal as possible. For example, he gave us one week in four off. We would be just encouraged to do research on our cryptanalytical methods. Of course, the research work should always be related to the job and we always wrote down what we were thinking in a huge book so that it could be preserved and some of those ideas were adopted and became part of the procedure. So I think Newman was the model administrator." (10)

Colossus Mark II

In February, 1944, the Lorenz SZ40 machine was further modified in an attempt to prevent the British from decyphering it. With the invasion of Europe known to be imminent, it was a crucial period for the codebreakers, as it was vitally important for Berlin to break the code being used between Adolf Hitler in Berlin and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Army in western Europe. (11)

Max Newman and Tommy Flowers now began working on a more advanced computer, Colossus Mark II. Flowers later recalled: "We were told if we couldn't make the machine work by June 1st it would be too late to be of use. So we assumed that that was going to be D-Day, which was supposed to be a secret." The first of these machines went into service at Bletchley Park on 1st June 1944. It had 2,400 valves and could process the tapes five times as fast. "The effective speed of sensing and processing the five-bit characters on punched paper tape was now twenty-five thousand characters per second... Flowers had introduced one of the fundamental principles of the postwar digital computer - use of a clock pulse to synchronize all the operations of his complex machine." (12) It has been pointed out that the speed of the Mark II was "comparable to the first Intel microprocessor chip introduced thirty years later". (13)

When the night staff arrived for work just before midnight on 4th June, 1944 they were informed that tomorrow was D-Day: "They told us that D-Day was today and they wanted every possible message decoded as fast as possible. But then it was postponed because the weather was so bad and that meant we girls knew it was going to take place, so we had to stay there until D-Day. We slept where we could and worked when we could and of course then they set off on June 6, and that was D-Day." (14)

Hilton enjoyed working at Bletchley Park. "I loved it. There is this enormous excitement in codebreaking, that what appears to be utter gibberish really makes sense if only you have the key and I could do that sort of thing for thirty hours at a stretch and never feel tired." (15) He later wrote, "It goes without saying that my colleagues were all extraordinarily good at their wartime jobs at Bletchley Park: they were intelligent, quick, inventive, immensely hard-working and always encouraging each other." (16)

Peter Hilton - Academic Career

In 1946 Hilton went to work with Professor Henry Whitehead at Oxford University. Whitehead worked in topology, a subject that "deals with those properties of geometric shapes that remain unchanged when the shape is bent, twisted, stretched or shrunk. Examples are whether the shape is connected or falls into several pieces, or more subtly, whether a closed curve is knotted." (17)

After completing his PhD thesis, he joined Max Newman and Alan Turing at University of Manchester. In 1949 he married the actress, Margaret Mostyn. Over the next few years she gave birth to Nicholas and Timothy. In 1956 he moved to Birmingham University as the Mason Professor of Pure Mathematics, a chair he held for four years.

"As an academic, Hilton (with other prominent mathematicians) created a new discipline in mathematics, homology theory, which despite its abstract-sounding name has practical applications, among them the classification of complicated surfaces in space. He also made significant contributions to other areas of mathematics: combinatorial geometry, combinatorics and number theory." (18)

In 1962 Peter Hilton became Professor of Mathematics at Cornell University. This was followed by periods at the University of Washington (1971–1973); Case Western Reserve University (1972–1982); State University of New York (1982–1993) and University of Central Florida (1994-1995). (19)

Peter Hilton died at Binghamton on 6th November 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) Peter Hilton, quoted by Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998)

I was recruited by a team looking for a mathematician with a knowledge of German... My knowledge of German was what I had taught myself in one year so I wasn't what they were looking for at all really. But I was the only person who turned up at the interview and they jumped at me and said: 'Yes, you must come.' So I had no right really in a sense to have this job. I loved it. There is this enormous excitement in codebreaking, that what appears to be utter gibberish really makes sense if only you have the key and I could do that sort of thing for thirty hours at a stretch and never feel tired.

Sometimes the German operator made the mistake of encyphering two successive messages using the same wheel setting. When he did this, we could combine the two encyphered texts and what we got was a combination of the two German messages. So you had one length of gibberish which was, in a certain sense, the sum of two pieces of German text. So you were tearing this thing apart to make the two pieces of text. And it's absolutely a marvellous process because you would guess some word, I remember once I guessed the word Abwehr. So that means you have a space and then Abwehr, eight symbols of one of the two messages. (By subtracting the Baudot elements for those letters from the characters in the combined text, Hilton would then be left with eight letters from the other message.)

The eight letters of the other message would have a space in the middle followed by Flug. So then you would guess: 'Well that's going to be Flugzeug - aircraft. So you get zeug followed by a space and that gives you five more letters of the other message. So you keep extending and going backwards as well. You break in different places and try to join up but then you're not sure if top goes with top, or top goes with bottom.

Then of course when you've got two messages like that, as a codebreaker, you have to take the encyphered message and the original text and add them together to get the key and then you have the wheel patterns. But for me the real excitement was this business of getting these two texts out of one sequence of gibberish. It was marvellous. I never met anything that was quite as exciting, especially since you knew that these were vital messages.

(2) Peter Hilton, quoted by Nigel Cawthorne, the author of The Enigma Man (2014)

This man came over to speak to me and said, "My name is Alan Turing. Are you interested in chess?" And so I thought, "Now I am going to find out what it is all about!" So I said, "Well, I am, as a matter of fact." He said, "Oh, that is good because I have a chess problem here I can't solve."

Alan Turing was unique. What you realize when you get to know a genius well is that there is all the difference between a very intelligent person and a genius. With very intelligent people, you talk to them, they come out with an idea, and you say to yourself, if not to them, I could have had that idea. You never had that feeling with Turing at all. He constantly surprised you with the originality of his thinking. It was marvellous.

(3) Peter Hilton, quoted by Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998)

He realised that he could get the best out of us by trusting to our own good intentions and our strong motivation and he made the thing always as informal as possible. For example, he gave us one week in four off. We would be just encouraged to do research on our cryptanalytical methods. Of course, the research work should always be related to the job and we always wrote down what we were thinking in a huge book so that it could be preserved and some of those ideas were adopted and became part of the procedure. So I think Newman was the model administrator.

(4) Peter Hilton, quoted by Alan Hodges, the author of Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983) pages 292-293

Alan Turing had to complete a form, and one of the questions on this form was: "Do you understand that by enrolling in the Home Guard you place yourself liable to military law?" Well, Turing, absolutely characteristically, said: "There can be no conceivable advantage in answering this question 'Yes' and therefore he answered it `No'. And of course he was duly enrolled, because people only look to see that these things are signed at the bottom. And so.., he went through the training, and became a first-class shot. Having become a first-class shot he had no further use for the Home Guard. So he ceased to constantly being relayed back to Headquarters and the officer commanding the Home Guard eventually summoned Turing to explain his repeated absence. It was a Colonel Fillingham, I remember him very well, because he became absolutely apopletic in situations of this kind.

This was perhaps the worst that he had had to deal with, because Turing went along and when asked why he had not been attending parades he explained it was because he was now an excellent shot and that was why he had joined. And Fillingham said, "But it is not up to you whether you attend parades or not. When you are called on parade, it is your duty as a soldier to attend." And Turing said, "But I am not a soldier." Fillingham: "What do you mean, you are not a soldier! You are under military law!" And Turing: "You know, I rather thought this sort of situation could arise," and to Fillingham he said: "I don't know I am under military law' And anyway, to cut a long story short, Turing said, "If you look at my form you will see that I protected myself against this situation." And so, of course, they got the form; they could not touch him; he had been improperly enrolled. So all they could do was to declare that he was not a member of the Home Guard. Of course that suited him perfectly. It was quite characteristic of him. And it was not being clever. It was just taking this form, taking it at its face value and deciding what was the optimal strategy if you had to complete a form of this kind. So much like the man all the way through.

(5) The Daily Telegraph (10th November 2010)

In 1941 Hilton was a young Oxford undergraduate when he was recruited to Bletchley to work in a section known as the Testery (after its head, a linguist called Major Ralph Tester). His colleagues there were Alan Turing; Roy Jenkins (the future Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer); Peter Benenson (who later founded Amnesty International); and Hugh Alexander, the British chess champion. Also there was Donald Michie, a young Oxford classics scholar who became a professor of artificial intelligence and whose various claims to fame included the post of curator of the Balliol Book of Bawdy Verse.

Hilton initially worked with Turing on breaking German naval codes produced by Enigma machines, and concentrated on top secret Offizier messages (for officers' eyes only). His extraordinary powers of visualisation meant that in his mind's eye he could unpick streams of characters from two separate teleprinters – a faculty that was to prove invaluable in the feverish mental chess game with the enemy.

Success rates were high and decryption was accomplished at remarkable speed. At the end of 1942 he was moved to work with a group of some 30 mathematicians on the yet more sophisticated code which the Germans had started using in 1940 to encrypt top-secret messages – mainly between Hitler and his generals.

Known by the irreverent nickname "Fish", these messages to and from the German High Command were produced by a much larger and more complex machine than Enigma.

Many years after the war, this was revealed to be a Lorenz SZ40 encoder, but at the time staff at Bletchley Park called it "Tunny". Hilton played one of the most important roles in the unit's cryptology department, monitoring any changes in "Tunny's" output and eventually becoming chief cryptanalyst on the "Tunny" project.

Codebreakers managed to work out how "Tunny" was constructed as a consequence of an operational slip by a German cipher operator in 1941. It was a crucial error. As a result, Bletchley Park cryptanalysts led by Hilton were able to work out the basic design and build an emulator they called Heath Robinson, after the cartoonist famous for drawing crackpot inventions.

But this proved far too slow at processing the data, and eventually a bigger and better version was developed. Colossus, as it was known, was the world's first programmable computer, weighed a ton, and could crack a Lorenz-encrypted message in hours rather than days. Eventually, 10 were built.

Occasionally German encoders failed to change the settings on their machines and two messages would be sent under the same "key" – a vital lapse in security that was known at Bletchley as a "depth". From this, decoders were able to produce a stream of "clear" (or deciphered text), that was a jumble of the two messages mixed together.

Using his startling ability to visualise two teleprinter streams, Hilton spent countless hours resolving the merged "depths" into individual messages in "clear", deriving "enormous excitement" in cracking what appeared at first to be "utter gibberish"."For me," he remembered, "the real excitement was this business of getting two texts out of one sequence of gibberish. I never met anything quite so exciting, especially since you knew that these were vital messages."

(6) Martin Childs, The Independent (9th December 2010)

Peter Hilton was a crucial member of the Bletchley Park code-breaking team that was of vital importance in helping secure the Allied victory in the Second World War, as well as becoming one of the most influential post-war mathematicians of his generation.

Hilton confessed that it was a long time before he found work which compared with the heady excitement of his days at Bletchley Park. General Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, said that the decoding successes at Bletchley Park shortened the war by at least two years, saving many thousands of lives.

Hilton was recruited to the Foreign Office under somewhat bizarre circumstances. With the order from Winston Churchill to recruit code-breakers, preferably mathematicians with knowledge of foreign European languages, interviewing boards were turning up at the country's leading universities. The combination was almost unheard of due to the premature specialisation in the British education system. They arrived in November 1941 at Oxford, where Hilton's tutor urged him to attend, although he was still an undergraduate and his German was self-taught and rudimentary. In the event, Hilton was the only candidate to present himself, and so was immediately offered a position.

Thus, on 12 January 1942, still uncertain as to what work he would be doing, Hilton presented himself at Bletchley Park and was escorted to Hut 8, where he was to work with some of the country's greatest mathematical minds. Colleagues included Alan Turing, who headed the team, developing the Enigma code-breaking machine and playing a huge role in the development of the computer; Peter Benenson, who later founded Amnesty International; Hugh Alexander, the British chess champion; Donald Michie, who became a Professor of Artificial Intelligence; and Roy Jenkins, future Chancellor of the Exchequer. Hilton got on especially well with Professor Henry Whitehead – they often shared a beer or two in the Bletchley pub that was subsequently renamed The Enigma – and when the war ended he was invited to return to Oxford as Whitehead's research student.

On his second day, Hilton began working with Turing on German naval codes produced by Enigma encryption machines, and concentrated on top secret Offizier messages (for officers' eyes only). His extraordinary ability to visualise meant that in his mind's eye he could unpick streams of characters from two separate teleprinters, a faculty that was to prove invaluable. His rapid deciphering of the convoluted messages provided the Allied forces with proposed German troop movements often hours before German generals in the field had been informed.

Hilton was a generous colleague and a committed enthusiast. He later wrote, "It goes without saying that my colleagues were all extraordinarily good at their wartime jobs at Bletchley Park: they were intelligent, quick, inventive, immensely hard-working and always encouraging each other." In 1942, he joined a team of more than 30 mathematicians in a section known as the Testery (after its head, linguist Major Ralph Tester), deciphering messages from Hitler's High Command to his generals.

The encryption became more complex and required even more sophisticated deciphering. The Germans' new Geheimschreiber [secret writer] machine was the "Lorenz SZ40" (nicknamed "Tunny" by the British). Hilton's ability to remember facts and figures proved vital and he became chief cryptanalyst on the "Tunny" project. Under his direction, his team worked out the basic design and built an emulator they called "Heath Robinson", after the cartoonist famous for his crackpot imaginary inventions. This, however, proved too slow at processing the data.

By February 1944, Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, had been built and was operational. It was able to crack a Lorenz-encrypted message in hours rather than days; eventually 10 were constructed. Occasional German incompetence meant that sometimes two messages were transmitted using the same key, and Hilton spent many hours utilising his astonishing ability to work on two teleprinters simultaneously: "For me, the real excitement was this business of getting two texts out of one sequence of gibberish. I never met anything quite so exciting, especially since you knew that these were vital messages."

(7) Ian Stewart, The Guardian (2nd December 2010)

In 1941, four of the UK's leading wartime codebreakers at Bletchley Park wrote to Winston Churchill. They included Alan Turing, renowned as one of the pioneers of computing and artificial intelligence, and a powerful and original mathematician. The letter urged Churchill to give the highest priority to the recruitment of more codebreakers and the provision of the necessary equipment. It was not sent through normal channels, but Churchill recognised its urgency and forwarded it to his chief of staff marked "action this day".

Soon afterwards, an interviewing board was searching for a mathematician with a strong knowledge of European languages. Given the high degree of specialisation in the educational system of the time, this was asking a lot. Only one candidate presented himself for interview, an undergraduate studying for a mathematics degree who had been teaching himself German for a year. His name was Peter Hilton, and he was appointed, even though neither he nor the interviewers knew what the job was. His official position was in the foreign office.

As a student at Oxford University, Hilton had trained for the Royal Artillery. However, he decided that if he followed that career path, he was likely to die young, "of sheer boredom", as he wrote in 1998 in Reminiscences of a Codebreaker.

So, on 12 January 1942, the young mathematician presented himself at Hut 8, Bletchley Park, where Turing asked him if he played chess. A day later he was told what his real job was: decoding secret German messages encrypted by the famous Enigma machines. Though he lived until the age of 87, Hilton always maintained that Bletchley Park was the most exciting part of his career. For most of his professional life he was a researcher and teacher specialising in an esoteric branch of pure mathematics, topology, at a number of British and then US universities.