Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan, the daughter of Thomas de Pizan, was born in Venice, on 11th September, 1364. She moved to Paris as a child of three when her father was appointed as doctor to King Charles V. Like most girls, Christine received very little education. However, her father did teach her to read and write as he "insisted that his daughter should be educated like a boy". (1)

From an early age Christine showed a fascination for books and the king agreed that she could use his royal library. The library contained over 900 books and was one of the largest in the world. (2) Christine later recalled: "One day I was surrounded by books of all kinds... my mind dwelt at length on the opinions of various authors whom I had studied... it made me wonder how it happened that so many different men - and learned men among them - have been and are so inclined to express... so many wicked insults about women and their behaviour... it seems that they all speak from one and the same mouth." (3)

When Christine was fifteen she married Etienne de Castel, one of the king's secretaries. The marriage was a happy one and within a few years Christine had three children. She called her husband a man "whom no other... could surpass in kindness, peacefulness, loyalty, and true love." (4)

At the age of 25 Christine de Pizan's life changed dramatically. Within a short period of time both her father and husband died. Neither man had sorted out his financial affairs and Christine spent the next thirteen years fighting in the courts for her inheritance. (5)

Christine's experiences in the courts had made her think about women's rights. She came to the conclusion that one of the reasons women were considered to be inferior to men was the way they were portrayed in literature. Christine believed that if women rather than men had written the books, the situation would have been very different. (6)

"Thinking deeply about these matters, I began to examine my character and conduct as a woman and, similarly, I considered other women whose company I frequently kept, princesses, great ladies, women of the middle and lower classes, who had told me of their most private and intimate thoughts... No matter how long I studied the problem, I could not see or realise how their (male writers) claims could be true when compared to the natural behaviour and character of women." (7)

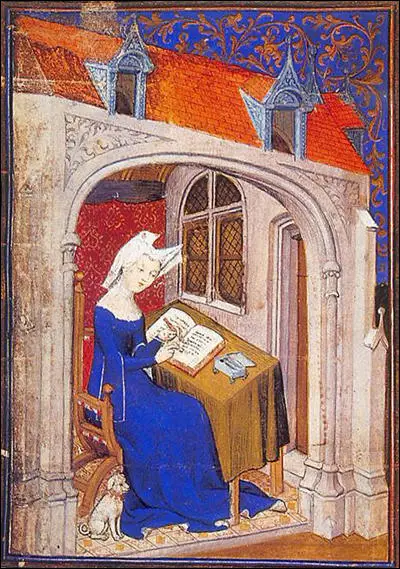

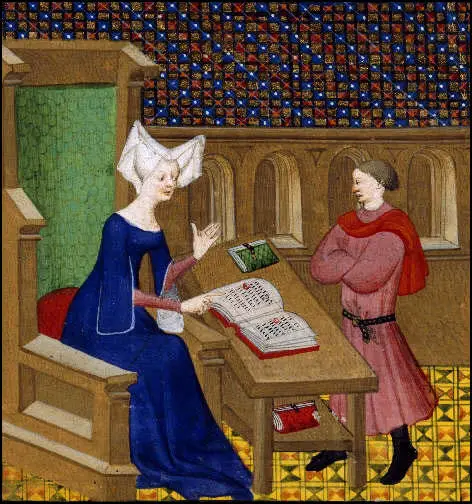

Christine de Pizan decided to try and earn a living as a writer, and applied herself to a course of training in history, science and poetry. In 1393 she began writing love poems, songs, and ballads. They were well received and she was encouraged to continue. By the late 1390s she was earning her living as a writer and is the "only known professional author in medieval Europe who was a woman". (8)

Christine de Pizan's The City of Ladies was published in 1405. It was the first history book written about women from the point of view of a woman. In the book Christine argues that male historians had given a distorted picture of the role played by women in history. The book attempted to redress the balance by providing a positive view of women's achievements and included a collection of stories about heroines of the past.

In the book she advocated the education of girls: "I am amazed by the opinion of some men who claim that they do not want their daughters or wives to be educated because they would be ruined as a result... Not all men (and especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very true that many foolish men have claimed this because it upset them that women knew more than they did." (9)

Kirstin Olsen points out that she used women to illustrate her books. (10) "Anastasia who is so learned and skilled in painting manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris... who can surpass her... People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the paintings of the great masters." (11)

Christine had now reached the conclusion that the male-dominated society in which she lived made it difficult for women to reach their full potential. Christine's next book, Three Virtues (1406), attempted to deal with this problem. This book gave advice on how women could improve their situation. Most of the book dealt with the lives of rich women. For example, Christine spent some time explaining how women could run their estates while their husbands were away from home. It has been described as "a manual of instruction for women in all walks of life on how to be virtuous and happy." (12)

Christine wrote several other books including a book on military law and a biography of King Charles V. "I gathered my information concerning his life, surroundings, behaviour life-style and his specific acts either from chronicles or from talking to famous people who are still alive." (13)

Christine was patronized by some of the greatest lords and ladies of medieval Europe, including the Dukes of Burgundy, Berry, Brabant, and Limburg, King Charles VI, and especially his wife Queen Isabella of Bavaria." (14) Her books were translated into several different languages and were very popular throughout the western world. Both Richard II and Henry IV tried to persuade Christine to live and work in England. Although Christine was tempted by these offers, she decided to remain in France for the rest of her life. (15)

She was devastated by the disastrous Battle of Agincourt and in 1418 retired to live in a convent. Her final work was a poem celebrating the achievements of Joan of Arc. In the poem Christine pointed out that it was a woman who had saved the kingdom of France, "something that 5,000 men could not have done." (16) Andrea Hopkins points out that the poem was "inspired by Joan's early victories... here was a woman worthy of Christine's ideals - an exemplar of feminine heroism". (17)

Christine de Pizan died in about 1430. Her works continued to be popular and when William Caxton started up the first printing works in England, one of the first authors he published was Christine de Pizan. In 1489 Henry VII asked Caxton to print a special English edition of Christine's book, Faytes of Arms, so that his knights would have the latest information on military technology. "The King... desired and willed me to translate this said book... and to print it to the end that every gentlemen born to arms and all men of war, captains, soldiers and all (who) should have knowledge how to behave... in battles." However, as it was feared that the knights would not be willing to listen to the advice of a woman on military matters, Christine's name was left off the cover of the book. (18)

Primary Sources

(1) Christine de Pizan, The Life of Charles V (1409)

I gathered my information concerning his life, surroundings, behaviour life-style and his specific acts either from chronicles or from talking to famous people who are still alive.

(2) Christine de Pizan, City of Ladies (1405)

One day I was surrounded by books of all kinds... my mind dwelt at length on the opinions of various authors whom I had studied... it made me wonder how it happened that so many different men - and learned men among them - have been and are so inclined to express... so many wicked insults about women and their behaviour... it seems that they all speak from one and the same mouth... Thinking deeply about these matters, I began to examine my character and conduct as a woman and, similarly, I considered other women whose company I frequently kept, princesses, great ladies, women of the middle and lower classes, who had told me of their most private and intimate thoughts... No matter how long I studied the problem, I could not see or realise how their (male writers) claims could be true when compared to the natural behaviour and character of women.

(3) Christine de Pizan, City of Ladies (1405)

I know a woman today, named Anastasia who is so learned and skilled in painting manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris... who can surpass her... People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the paintings of the great masters.

(4) Christine de Pizan, City of Ladies (1405)

I am amazed by the opinion of some men who claim that they do not want their daughters or wives to be educated because they would be ruined as a result... Not all men (and especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very true that many foolish men have claimed this because it upset them that women knew more than they did.

(5) Christine de Pizan, a poem in defence of women (c. 1410)

They neither kill nor wound, nor lop off limbs,

They do not plot, or plunder or persecute.

(6) William Caxton explaining why he printed Christine de Pizan's book on military tactics, Faytes of Arms. (1489)

The manuscript... in French was delivered to me by my sovereign lord King Henry VII... The King... desired and willed me to translate this said book... and to print it to the end that every gentlemen born to arms and all men of war, captains, soldiers and all (who) should have knowledge how to behave... in battles.

(7) Christine de Pizan, Joan of Arc (1429)

She (Joan of Arc) drives her enemies out of France, recapturing castles and towns. Never did anyone see greater strength, even in hundreds of thousands of men... What honour for the female sex... the whole Kingdom - now recovered and made safe by a woman... And so, you English, draw in your horns... A short time ago, when you looked so fierce, you had no idea that this would be so... You thought you had already conquered France and that she must remain yours. Things have turned out otherwise, you treacherous lot! Go and beat your drums elsewhere, unless you want to taste death, like your companions.

(8) Kirstin Olsen, Remembering the Ladies (1988)

Christine de Pizan was unquestionably one of the most extraordinary women of her age, yet few people today, except for some feminist scholars and historians, have heard of her. She was one of the West's first feminists, its first professional writers of her day, and one of the first vernacular authors to oversee the illustration of her books - all remarkable accomplishments, especially since at the time most women could neither read nor write.

(9) Andrea Hopkins, Heroines: Remarkable and Inspiring Women (1995)

Christine de Pizan was the only known professional author in medieval Europe who was a woman. She was celebrated writer in her day, although her work was somewhat neglected until interest in feminist studies revived her importance...

Part of the reason we know so much about Christine de Pizan is that many of her works contain autobiographical details, something quite rare among medieval writers. Her major works began with her long poem The Changes of Fortune, in which she used examples from her own life as well as those of more famous characters to show how fortune can cast down the the prosperous and raise up the humble.

Student Activities

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Farming (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)