Henry Cantwell Wallace

Henry Cantwell Wallace, the son of Henry Wallace, Sr., was born in Rock Island, Illinois, on 11th May, 1866. His father was a Presbyterian minister who served as a chaplain with the Union Army during the American Civil War. An experience that gave him a permanent horror of war.

Henry Wallace, Sr., was told he was dying of tuberculosis, a disease that had virtually destroyed his entire family. Over a period of twelve years, his seven brothers and sisters and his father had all died of "some sort of lung trouble". None of his siblings reached the age of thirty. With a small inheritance left by his father, he purchased some farming land in Adair County in Iowa. In 1877 he left the ministry and with his wife and five small children he moved to Winterset.

Wallace brought a modern approach to farming. He was especially concerned about the problem of land erosion. His grandson, Henry Agard Wallace, later recalled: "To see rich land eaten away by erosion, to stand by a continual cultivation on sloping fields wears away the best soil, is enough to make a good farmer sick at heart. My grandfather watching this process years ago used to speak of the voiceless land. In our time we have seen the process reach an acute stage, and we have at last begun to take to heart the meaning of soil exploitation."

Wallace argued his case in the Madisonian newspaper. He also purchased the Winterset Chronicle , a newspaper with only 400 readers. In ten months the circulation increased to 1,400. As well as writing about scientific farming he introduced on his farm the first shorthorn bull, the first purebred hog, and the first Percheron horse to Adair County. He also pioneered the idea of growing clover to enrich the soil while feeding animals.

In 1883 he helped establish the Agricultural Editors Association, to promote independent farm journalism and the Iowa Improved Stock Breeders Association to foster modern livestock practices. He was also appointed editor of the Iowa Homestead . He argued: "The paper of which I was then editor was not really so much of an agricultural paper as it was an anti-monopoly paper."

Henry Cantwell Wallace was brought up by his father to understand farming matters and in 1885 he went to Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames. He later pointed out: "The college was nominally an agricultural college, but very little agriculture was taught." Hard-working and quick-witted he soon got the impression that he knew more than his teachers.

In the summer of 1887 Wallace discovered that one of his father's tenants planned to leave. He asked his father: "How would you like to have me for a tenant, on the same terms you have been renting for?" His father agreed and he now proposed marriage to May Brodhead, a young woman he had met at college. She had been born in New York City and had never lived on a farm. However, Wallace had "made farming seem most romantic". The couple were married on 24th November, 1887. Their first child, Henry A. Wallace, was born on 7th October, 1888.

Wallace raised purebread shorthorn cattle, Poland China hogs, Percheron horses on his farm near the town of Orient in Iowa. He found life difficult as the prices for cattle and hogs was falling dramatically. After the birth of their second child, Annabelle in 1891, Wallace began considering giving up farming. In 1892 he accepted a position the position of "professor of agriculture" at the Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames.

Henry A. Wallace had very few friends as a child but did develop a close relationship with George Washington Carver, one of his father's students. Carver, born into slavery in Missouri in 1864, was fascinated by plants. Wallace later recalled that Carver "took a fancy to me and took me with him on his botanizing expeditions and pointed out to me the flowers and the parts of flowers - the stamens and the pistil. I remember him claiming to my father that I had greatly surprised him by recognizing the pistils and stamens of redtop, a kind of grass... I also remember rather questioning his accuracy in believing that I recognized these parts, but anyhow he boasted about me, and the mere fact of his boasting, I think, incited me to learn more than if I had really done what he said I had done."

Wallace, like his father, was interested in agricultural journalism. Together with a fellow faculty member, Charles F. Curtiss, he purchased the Iowa Farmer and Breeder , a small livestock journal published twice a month. After taking control of it they changed its name to Farm and Dairy . In 1894 he created a great deal of controversy by questioning the integrity and scientific findings of a well-known local chemist. As a result of the article Wallace was forced to resign from the Iowa State Agricultural College.

Wallace's father was also having problems. James Pierce, the publisher of Iowa Homestead , objected to his anti-monoploy stance. He was also ordered to write favourable stories about a Chicago's firm agricultural products. Wallace Snr. later discovered that this was in return for a lucrative advertising contract. When he resisted these orders he was fired as editor of the journal. Henry Wallace, almost sixty years old, and his son were both without jobs.

It was eventually decided to join forces to publish a new journal, Wallaces' Farm and Dairy . In the first edition on 18th September, 1896, Henry Cantwell Wallace explained the background to the venture: "Mr. Wallace was for ten years, up to February 1895, the editor of the Iowa Homestead. His withdrawal from the paper was the culmination of trouble between him and the business manager as to its public editorial policy, Mr. Wallace wishing to maintain it in its old position as the leading western exponent of anti-monopoly principles. Failing in this he became the editor of the Farm and Diary, over the editorial policy of which he has full control."

The journal was a great success. Henry Cantwell Wallace later wrote: "That year, 1895, is one of the most memorable of my life. It brought me what seemed to be one of my greatest troubles, and witnessed the beginning of my greatest success. Above all, it made me understand more completely than ever before that people generally will stand by a man when they see that he is serving them faithfully." H. G. McMillan, the state Republican Party chairman, claimed that Wallace was "without doubt the ablest and most forceful agricultural writer of his day."

Wallace and his newspaper supported William McKinley in the 1896 Presidential Election against his opponent, William Jennings Bryan. James Pierce argued in the Iowa Homestead that Wallace had accepted a bribe to publish his anti-Bryan articles. He claimed "Henry Wallace is charged with selling his opinions and changing them to make them salable." Wallace took Pierce to court and eventually won a $1,500 judgment: "It was regarded as a very unusual thing, in fact, almost unheard of, for one publisher to secure judgment against another publisher for libel. I would not have brought the suit but for the evident maliciousness of Mr. Pierce's article, and I thought it was time to put a stop to this sort of thing."

After the election H. G. McMillan asked Wallace whether he was willing to be Secretary of Agriculture in McKinley's government. He refused the offer but did suggest that his great friend, Tama Jim Wilson, would make an ideal appointment. Wilson was a former professor of agriculture at the Iowa State Agricultural College. He accepted the post and went on to hold the position for the next sixteen years. It was the longest cabinet tenure in American history.

In December 1898 Wallace changed the name of his journal to Wallaces' Farmer . He added a credo that summed up in six words what they and their paper stood for: "Good farming, clear thinking, right living." According to one source: "There was a page devoted to news about hogs, a page for diary farmers, a horticulture page, a market page, and... a page sprinkled with inspirational poems, recipes, and housemaking tips."

Within two years of its founding the newspaper had around 20,000 paying subscribers. After five years they had repayed all their debts and Henry and his father were receiving good salaries. They also moved into a modern building in downtown Des Moines. By 1902 Henry Wallace had enough money to buy ten acres on the west side and was able to construct a new home that cost more than $5,000. Ten years later he purchased a brick mansion that cost over $50,000.

Wallace's son, Henry Agard Wallace, entered Iowa State Agricultural College in 1906. Professor J.L. Lush claimed that "he (Wallace) was healthily skeptical of many things he was taught in class and was constantly challenging them." A fellow student commented: "He always wanted to know why and could spend considerable time discussing some particular matter with a teacher. He was always a thinker... He was half a jump ahead of the instructors in some classes."

In the summer of 1909 his son began producing material for Wallaces' Farmer. His first project was a three month tour of the American West, from the dusty plains of Texas to the great agricultural valleys of California. He traveled mainly by train and at each place he visited he produced an article on the state of its agriculture. He was paid by the inch and earned enough to pay his college expenses during the next year. After leaving college in 1910 he worked full-time for the newspaper.

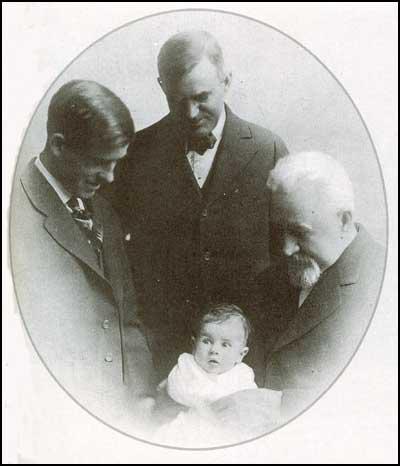

with the latest addition to the family, Henry Browne Wallace.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 created serious problems for farmers in Europe. To survive, the countries involved in the conflict had to increase its imports of food. This increased prices and profits. Wallaces' Farmer reported in 1916: "Dare we assume that the great Ruler plunges half the world into war, that the other half may profit by the manufacture of war materials and the growing of foodstuffs? Who are we, and what have we done, that material blessings should be showered upon us so lavishly?" Wallace also warned about what might happen to agricultural in the years to follow: "Ultimately the United States will have to bear its share of the burden of this war, but very likely for a year, and possibly for two or three years, after the war ends, we will continue on the high tide of prosperity, to be followed by a depression lasting for a number of years... Now would be a good time to reduce your debts."

On the death of his father, Henry Wallace, Sr., in February 1916, Henry Agard Wallace became joint editor of the Wallaces Farmer. He had been inspired by his grandfather to devote his life to the community. Russell Lord, the author of The Wallaces of Iowa (1947), has pointed out: "We know that his great desire was that in his descendants should be multiplied his power for good; that they should live worthily; that they should keep untarnished the family name which he so jealously guarded; that they should always and everywhere be men and women whom he could honor and respect that they should carry on the work which he began."

On 2nd April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. The Wallaces Farmer reluctantly gave its support to America's involvement in the First World War. On the 6th April it commented: "At the bottom, this whole business is a struggle to maintain the ideals upon which this great American republic was founded, and for which, when the pinch comes, are always ready to fight. Emperors fight for commercial supremacy, for extension of their domain, for their right to rule. Democracies fight for human liberty, for the rights of man."

In his newspaper Henry Cantwell Wallace urged President Wilson to take action to protect agriculture. In August, 1917, Wilson responded by appointing Herbert Hoover to head the recently created Office of Food Administration. Hoover was aware that there was a shortage of fat in the European diet. He thought the best way to solve this problem was to increase the export of pork to Europe. Farmers were reluctant to invest in breeding hogs because of the low prices they were commanding at market.

In October 1917 Hoover decided to establish a Swine Commission to look at methods to persuade farmers to increase hog production. He invited Henry Cantwell Wallace and Henry Agard Wallace to join the commission. In its report it suggested that the government guarantee the price of hogs at a rate of return of at least 14.3 to 1 (the price of 14.3 bushels of corn would equal 100 pounds of live hog). Hoover rejected the idea but in November he established the minimum price as 13 to 1. Wallace denounced the Food Administration's position as "illogical, unjust and ridiculous". Hoover wrote to Wallace explaining his position. Wallace replied that "hog farmers needed profits, not carefully crafted words."

This began a long-drawn out conflict between Hoover and the Wallace family. In February 1920, an editorial in the Wallaces Farmer condemned Hoover for trying "to bamboozle the farmers" and expressing the opinion that he was denying farmers the ability to make a reasonable profit: "If we were asked to name one man who is more responsible than any other for starting the dissatisfaction which exists among the farmers of the country, we would instantly name Mr. Hoover." Hoover tried several times to make his peace with Wallace but he refused to back-down. As his friend, Gifford Pinchot, pointed out: "Wallace was a natural-born gamecock. He was red-headed on his head and in his soul."

In 1920 William Squire Kenyon recommended Wallace to the Republican Party presidential nominee, Warren Harding. Kenyon wrote: "The best man I know of in the whole United States, with reference to agriculture is Mr. Henry Wallace. He is a sturdy Scotchman, staunch, level-headed, and knows agricultural problems." John C. Culver and John C. Hyde, the authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) have pointed out: "Different as they were and they were vastly different - Harding and Wallace developed a friendly rapport. For his part, Wallace regarded Harding as something of a blank slate upon which agricultural campaign policy could be written. In large measure he succeeded. He pressed hard for attention to agricultural issues during the campaign, suggested heavy reliance on the pro-agriculture plank in the Republican platform, and contributed the lion's share of Harding's major farm speech, delivered at the Minnesota State Fair in early September."

Wallace advised Harding throughout the campaign and was considered to be an important factor in his victory. As expected, Wallace was appointed as Secretary of Agriculture. He told his readers: "I will do the best I know." Also in the cabinet was Herbert Hoover who had been appointed by Harding as Secretary of Commerce. In a letter to the head of a special congressional reorganization committee, Hoover suggested the Agriculture Department be stripped of all marketing functions, foreign and domestic. Wallace was furious as he saw Hoover's plan as a power grab.He argued that if the proposal was accepted it would reduce the department to a "sort of glorified extension service" concerned only with helping farmers produce more crops so they could "sell them for what the buyer is willing to pay." Harding accepted his arguments and the department was not changed.

Wallace was expected to come up with ideas to solve the problem of falling corn prices in 1921. His son, Henry Agard Wallace, was one of those making suggestions. In the Wallaces Farmer he argued that the only way to increase the price of corn was to reduce production. He told his readers that they should take 10 per cent of their land out of corn production and cover it with a nitrogen-building legume such as clover. The resulting drop in supply would increase prices and enrich both farmers and their land: "After everything has been taken into account, the fact remains that we have far more corn than we need."

Henry Agard Wallace also suggested a government-operated storage system. He got the idea from a book written by Chen Huan-chang, that described a grain storage system established in China in 54 B.C. "When the price of grain was low, the province should buy it at the normal price, higher than the market price, in order to profit the farmers. When the price was high, they should sell it at the normal price, lower than the market price, in order to profit the customers." The book explained that the storage system survived in various forms for fourteen hundred years. Wallace urged the government to take similar action: "If any government shall ever do anything really worth while with our food problem it will be by perfecting the plan tried by the Chinese 2,000 years ago; that is, by building warehouses and storing food in years of abundance and holding it until the years of scarcity."

George N. Peek and Hugh S. Johnson developed a plan for government aid. In January 1922, they sent their proposal, Equality for Agriculture , to Wallace and the Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. They warned Wallace and Hoover that if it was rejected by the Republican Party the "essential principles deduced in the brief will seriously embarrass it in the coming election, if not permanently." Hoover was not impressed with the Peek-Johnson proposal and instead put forward his own plans for agricultural recovery.

Wallace was more sympathetic but rejected it because it did nothing to curtail production. He argued that too much land was in production; too much soil was being destroyed to grow corn that nobody needed. Wallace urged President Warren Harding to take action but he believed in laissez-faire and was reluctant for the government to interfere with market-forces. The debate came to an end when Harding died suddenly on 2nd August, 1923.

Wallace now approached Senator Charles L. McNary of Oregon and Representative Gilbert N. Haugen of Iowa to serve as the sponsors of his plan. This eventually became known as the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Bill that proposed a federal agency would support and protect domestic farm prices by attempting to maintain price levels that existed before the First World War. It was argued that by purchasing surpluses and selling them overseas, the federal government would take losses that would be paid for through fees against farm producers. The bill was passed by Congress in 1924 but was vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge.

Henry Agard Wallace in the Wallaces Farmer had campaigned strongly for McNary-Haugen bill. He wrote that politicians were "willing to entertain a feeling of sympathy for farmers who are having a hard time, provided that sympathy costs them nothing and further provided that they are not asked to cease worshiping at the shrine of laissez-faire." President Coolidge was very angry with his Secretary of Agriculture but was warned against sacking a man who was so popular with farmers at a time when the presidential election was less than a year away.

In September, 1924, Wallace made a speech where he argued: "The men of vision must arise soon if the United States is to be saved from the fate of becoming a preponderantly industrial nation in which there is not a relation of equality between agriculture and industry.... They must set the minds of the farmers on fire with the desire for a rural civilization carrying sufficient economic satisfaction, beauty, and culture to offset completely the lure of the city."

Henry Cantwell Wallace went into hospital for the removal of his gall bladder. The operation took place on 15th October, 1924. It was deemed a success and was working from his hospital bed when he became seriously ill. His doctor diagnosed the problem as toxemic poisoning and he died on 25th October. He was 58 years old at the time of his death.

His son wrote in the next edition of the Wallaces Farmer: "The fight for agricultural equality will go on; so will the battle for a stable price level, for controlled production, for better rural schools and churches, for larger income and higher standards of living for the working farmers, for the checking of speculation in farm lands, for the thousand and one things that are needed to make the sort of rural civilization he labored for and hoped to see. He died with his armor on in the fight for the cause which he loved."

Primary Sources

(1) Henry Cantwell Wallace, Wallaces' Farm and Dairy (18th September, 1896)

Mr. Wallace was for ten years, up to February 1895, the editor of the Iowa Homestead. His withdrawal from the paper was the culmination of trouble between him and the business manager as to its public editorial policy, Mr. Wallace wishing to maintain it in its old position as the leading western exponent of anti-monopoly principles. Failing in this he became the editor of the Farm and Diary, over the editorial policy of which he has full control.

(2) Wallaces Farmer (24th November, 1916)

Dare we assume that the great Ruler plunges half the world into war, that the other half may profit by the manufacture of war materials and the growing of foodstuffs? Who are we, and what have we done, that material blessings should be showered upon us so lavishly?

(3) Wallaces Farmer (29th December, 1916)

Ultimately the United States will have to bear its share of the burden of this war, but very likely for a year, and possibly for two or three years, after the war ends, we will continue on the high tide of prosperity, to be followed by a depression lasting for a number of years... Now would be a good time to reduce your debts.

(4) Wallaces Farmer (29th December, 1916)

At the bottom, this whole business is a struggle to maintain the ideals upon which this great American republic was founded, and for which, when the pinch comes, are always ready to fight. Emperors fight for commercial supremacy, for extension of their domain, for their right to rule. Democracies fight for human liberty, for the rights of man.

(5) John C. Culver and John C. Hyde, American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001)

Different as they were and they were vastly different - Harding and Wallace developed a friendly rapport. For his part, Wallace regarded Harding as something of a blank slate upon which agricultural campaign policy could be written. In large measure he succeeded. He pressed hard for attention to agricultural issues during the campaign, suggested heavy reliance on the pro-agriculture plank in the Republican platform, and contributed the lion's share of Harding's major farm speech, delivered at the Minnesota State Fair in early September. Wallace personally wrote a flier called "Heart to Heart Talk to Farmers" and helped devise a newspaper advertisement attacking the Democrats' "unwise, unsympathetic agricultural policies."

In November, Harding and Calvin Coolidge smashed the Democratic ticket, the publisher James Cox and young Franklin D. Roosevelt, at the polls. The Republicans carried every state outside the Deep South. In the event of victory, Harding notified the farm editor three days before the election, "I shall very much want your assistance in making good the promises which we have made to the American people."

Friends began congratulating Harry Wallace well before any cabinet appointments were announced. "I take it that you will be the next Secretary of Agriculture," Iowa State professor John Evvard wrote.

Virtually all of the major farm organizations backed him; only the Farmers' Union opposed him. Kenyon publicly declared that nothing would be so beneficial to the Republic as Wallace's selection. So certain did Wallace's appointment seem that Edwin Meredith wrote to offer his assistance in the transition. The Des Moines Register editorially commented that no one was more certain than Henry C. Wallace to sit in Harding's cabinet. It was all a bit embarrassing to Wallace. "The only thing I can do is grin a sickly grin and talk about something else," he wrote to his brother Dan.

Few outside the Wallace family understood how truly reluctant he was to take the post. Harry still recalled the day he asked his own father why he had not pursued the chance to become secretary of agriculture. "No Wallace has ever held an office higher than Justice of the Peace, and I didn't want to mar the family record," Uncle Henry quipped. Deep within him, Harry felt his father was right. Gifford Pinchot, who was staying at the Wallaces' home when the formal offer to join the administration was received, said Harry nearly rejected it. "I urged him as strongly as I could to take the place, believing that in so doing lay the line of greatest usefulness," Pinchot recalled.

(6) Henry Agard Wallace, Wallaces Farmer (4th November, 1924)

The fight for agricultural equality will go on; so will the battle for a stable price level, for controlled production, for better rural schools and churches, for larger income and higher standards of living for the working farmers, for the checking of speculation in farm lands, for the thousand and one things that are needed to make the sort of rural civilization he labored for and hoped to see. He died with his armor on in the fight for the cause which he loved.