John Metcalf

John Metcalf was born in Knaresborough, the son of a horse breeder, on 15th August 1717. He came from a poor family and at the age of six he went blind after an attack of smallpox. (1)

According to his own account, "in the space of three years" he was able to "find his way to any part of the town of Knaresborough" and had "begun to associate with boys of his own age". During this period he became a talented horseman. (2)

Despite his blindness he "became an accomplished rider, swimmer, and card player. He enjoyed a wager and was involved in cockfighting, horse-racing, and philandering. Metcalf played the violin and oboe and from the age of fifteen earned a living entertaining wealthy visitors to the rapidly developing spa of Harrogate." (3)

John Metcalf developed a relationship with a local innkeeper's daughter, Dorothy Benson. They "became very intimate, and this intimacy produced mutual regard and confidence". (4) However, he was forced to leave the town after he made another young woman pregnant. "Notwithstanding his mischievous tricks and youthful wildness, there must have been something exceedingly winning about the man, possessed, as he was, of a strong, manly, and affectionate nature." When the woman was asked why she behaved in this way, she replied: "His actions are so singular, and his spirit so manly and enterprising, that I could not help loving him." (5)

He travelled to the coast and at Whitby boarded a ship for London. Metcalf, who was over 6 feet tall, got involved in a fight with John Blake, a local "champion" after he was accused of cheating at cards. He claimed that he "entered into combat with this ruffian" until he "cried for mercy". In his autobiography Metcalf suggested "to the fame" he had "acquired by various means, was now added that of a boxer". (6)

Metcalf returned to Knaresborough in 1739 and married Dorothy Benson. The couple had four surviving children. In addition to continuing his career as a musician Metcalf established a business carrying fresh fish from the coast to Leeds and Manchester. In 1751, when he was thirty-four years old, Metcalf established a stage-wagon service between York and Knaresborough. (7)

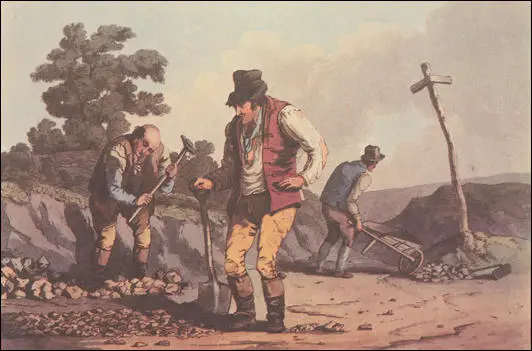

This work made him fully aware of the poor state of the roads. Daniel Defoe, explained in his book, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724) that to be successful, collieries needed to be close to water "for once the rains come in, it (the road) stirs no more that year, and sometimes a whole summer, is not dry enough to make roads passable." (8)

The rapid increase in industrial production between 1700 and 1750 resulted in the need for an improved transport system. Whenever possible, factory owners used Britain's network of rivers to transport their goods. However, their customers did not always live by rivers and they therefore had to make use of Britain's roads. (9)

The appalling state of Britain's roads created serious problems for factory owners. Bad weather often made roads impassable. When fresh supplies of raw materials failed to arrive, factory production came to a halt. Flooded roads also meant that factory owners had difficulty transporting the finished goods to their customers. Merchants and factory owners appealed to Parliament for help.

After much discussion it was decided that this problem would only be solved if road building could be made profitable. Groups of businessmen were therefore encouraged to form companies called Turnpike Trusts. These companies were granted permission by Parliament to build and maintain roads. So that they could make a profit from this venture, companies were allowed to charge people to use these roads. Between 1700 and 1750 Parliament established over 400 of these Turnpike companies. The quality of the roads built by these companies varied enormously. Some companies tried to increase their profits by spending very little money on repairing their roads. (10)

In 1752 the first Turnpike Act in the locality authorized a route between Boroughbridge and Harrogate. Metcalf approached Thomas Ostler, the surveyor, and despite a complete lack of experience in road building, was contracted to build a 3 mile section, which he successfully completed ahead of schedule. (11)

He was also awarded the contract to build a bridge at Boroughbridge. He completed the bridge successfully and by August 1754 had received over £500 for his work. Metcalf sold his stage-wagon business in order to concentrate on this new and more profitable career. (12)

Metcalf did not always make a profit from his road building. He offered to build the road between Skipton and the River Colne. "There were four miles of road to be made, and estimates were advertised for." Metcalf got the contract but as the "materials were at a greater distance, and more difficult to be procured, than expected, and a wet season coming on, made this a bad bargain." Despite this Metcalf "completed it according to contract". (13)

Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) has pointed out: "One of the pioneers of road construction was the extraordinary figure of Jack Metcalf from Knaresborough in Yorkshire.... The Turnpike Trust commissioned Metcalf to build a series of roads that were able to carry; heavy wagons and withstand wet weather. His innovation was to build strong foundations under the road surface, and to use a convex surface to enhance drainage, with gutters running down either side. Metcalf used rafts to build roads across bogs and was an astute surveyor, able to calculate materials and costs accurately. He went on building roads across the north of England, giving manufacturers and commercial travellers easier access to markets and canals and ports." (14)

His next major contract was a 6 mile stretch between Harrogate and Harewood, near Leeds, for which he received £1200. As Metcalf's reputation grew he was awarded contracts in other parts of Yorkshire and, subsequently, in Lancashire, Derbyshire, and Cheshire. A contemporary noted that Metcalf was "a projector and surveyor of highways in difficult and mountainous parts" using only his staff as a guide. (15) According to Samuel Smiles, he sometimes got jobs because he kept his blindness from the people who gave out the contracts. (16)

Metcalf frequently undertook projects that other people refused. "In order to deal with marshy areas he devised a method of laying heather and gorse as the foundation and building the road on top. This proved very successful and in many places enabled a more direct route to be taken. He built several stretches of moorland road linking Yorkshire and Lancashire and altered many routes in the Peak District." (17)

In the summer of 1778 Metcalf took his wife Dorothy to Stockport, in order to seek a cure for her rheumatism. In his autobiography he explained: "human aid proved ineffectual. and she died after thirty-nine years of conjugal felicity, which was never interrupted but by her illness." (18)

Metcalf continued to work to 1792 when he was seventy-five years old. In the course of his career Metcalf had constructed over 120 miles of high-quality road, for which he received in excess of £40,000. "Metcalf attributed his success to his excellent memory for detail, which had developed as a result of his blindness. He made a valuable contribution to communications in the late eighteenth century by improving routes and thus enabling wheeled vehicles to move more easily in the critical period of rapid industrial expansion". (19)

John Metcalf, died, aged ninety-two, in Spofforth, on 27 April 1810.

Primary Sources

(1) Christine S. Hallas, John Metcalf : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

He (John Metcalf) was sent to school at the age of four but two years later became blind after an attack of smallpox. Despite his blindness he became an accomplished rider, swimmer, and card player. He enjoyed a wager and was involved in cockfighting, horse-racing, and philandering. Metcalf played the violin and oboe and from the age of fifteen earned a living entertaining wealthy visitors to the rapidly developing spa of Harrogate. He was also a successful horse dealer.

According to the Memoirs that Metcalf published in 1795, at the age of twenty he became enamoured of a local innkeeper's daughter, Dorothy Benson (1716/17–1778), but, owing to an indiscretion with another woman, had to leave the area. He travelled to the coast and at Whitby boarded a ship for London. While in the capital he renewed some of his earlier contacts. One of these acquaintances, Colonel , was about to travel to Harrogate and offered to take Blind Jack with him. However, Jack, aware of the poor condition of the roads, struck a wager that he would get to Harrogate more quickly on foot than by coach. Jack took five and a half days to walk about 210 miles and won the wager.

(2) Roger Osborne, Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013)

One of the pioneers of road construction was the extraordinary figure of Jack Metcalf from Knaresborough in Yorkshire. Blind from the age of six, Metcalf already had a colourful career as a fiddle-player, soldier, gambler and trader before setting up in the 1740s as a haulier of goods from Leeds to Manchester and Knaresborough to York. He had developed a stagecoach line in the north of England when a turnpike trust was set up in his area in 1765; the trust commissioned Metcalf to build a series of roads that were able to carry; heavy wagons and withstand wet weather. His innovation was to build strong foundations under the road surface, and to use a convex surface to enhance drainage, with gutters running down either side. Metcalf used rafts to build roads across bogs and was an astute surveyor, able to calculate materials and costs accurately. He went on building roads across the north of England, giving manufacturers and commercial travellers easier access to markets and canals and ports.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Samuel Smiles, Lives of the Engineers (1861) page 74

(2) John Metcalf, Life of John Metcalf (1795) page 2

(3) Christine S. Hallas, John Metcalf : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(4) John Metcalf, Life of John Metcalf (1795) page 32

(5) Samuel Smiles, Lives of the Engineers (1861) page 77

(6) John Metcalf, Life of John Metcalf (1795) page 44

(7) John Metcalf, Life of John Metcalf (1795) page 123

(8) Daniel Defoe, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724) page 144

(9) Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007) page 118

(10) George M. Trevelyan, English Social History (1942) page 398

(11) John Metcalf, Life of John Metcalf (1795) page 125

(12) Christine S. Hallas, John Metcalf : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(13) John Metcalf, Life of John Metcalf (1795) pages 130-131

(14) Roger Osborne, Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) page 259

(15) G. Bew, Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (1785) page 173

(16) Samuel Smiles, Lives of the Engineers (1861) page 75

(17) Christine S. Hallas, John Metcalf : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(18) John Metcalf, Life of John Metcalf (1795) page 147