Turnpike Trusts

At the end of the 17th century, British roads were in a terrible state. A law passed in 1555 instructed local people to maintain the roads in their area. Every parish through which a road passed was legally bound to maintain it by six days a year of unpaid labour. In many area, this law was ignored. Even in those parishes where repairs were carried out, as there was no outside supervision, it was usually just a case of people putting stones and gravel in the worst potholes. Little, if any, attention was given to drainage, and so during the winter these roads often became a sea of mud. (1)

During this period coal was the most important cargo on British roads. In the 1670s around 2 million tons a year were being moved around Britain. Around one million tons by sea and a quarter of a million tons by inland rivers. Daniel Defoe, explained in his book, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724) that to be successful, collieries needed to be close to water "for once the rains come in, it (the road) stirs no more that year, and sometimes a whole summer, is not dry enough to make roads passable". (2)

Hauliers came to collieries with horses and carts to collect coal. It is estimated that it would take ten pack-horses or a very large cart, to carry a ton of coal, so even a small colliery producing a few thousand tons a year would create a huge amount of traffic, often along unmade tracks. When bad weather made these tracks or roads impassable coal was left piled at collieries. (3)

In 1748 Pehr Kalm, the Swedish explorer visited England. He told a friend that he was very unimpressed with the quality of British roads: "In Sweden the road is higher than the land around, but here exactly the opposite is the case... In this country very large wagons are used with many horses... Through many years' driving, the wagons seem to have eaten down into the ground... to a depth of two, four, or six feet." (4)

The rapid increase in industrial production between 1700 and 1750 resulted in the need for an improved transport system. Whenever possible, factory owners used Britain's network of rivers to transport their goods. However, their customers did not always live by rivers and they therefore had to make use of Britain's roads. This was a major problem for mine-owners as transport costs were crucial. If they could not get their coal to market at a competitive price, they were out of business. (5)

The appalling state of Britain's roads created serious problems for factory owners. Bad weather often made roads impassable. When fresh supplies of raw materials failed to arrive, factory production came to a halt. Flooded roads also meant that factory owners had difficulty transporting the finished goods to their customers. Merchants and factory owners appealed to Parliament for help.

After much discussion it was decided that this problem would only be solved if road building could be made profitable. Groups of businessmen were therefore encouraged to form companies called Turnpike Trusts. These companies were granted permission by Parliament to build and maintain roads. So that they could make a profit from this venture, companies were allowed to charge people to use these roads. Between 1700 and 1750 Parliament established over 400 of these Turnpike companies. (6)

The quality of the roads built by these companies varied enormously. Some companies tried to increase their profits by spending very little money on repairing their roads. Other companies made every effort to provide a good service. In 1765, Harrogate Turnpike Trust employed John Metcalf to build a three-mile stretch of road in Yorkshire. Although blind since the age of six, Metcalfe was able to make an extremely good road. Metcalfe was aware of the importance of efficient drainage, and his decision to dig ditches along the sides of his convex roads considerably reduced the possibility of flooding. (7)

Metcalf did not always make a profit from his road building. He offered to build the road between Skipton and the River Colne. "There were four miles of road to be made, and estimates were advertised for." Metcalf got the contract but as the "materials were at a greater distance, and more difficult to be procured, than expected, and a wet season coming on, made this a bad bargain." Despite this Metcalf "completed it according to contract". (8)

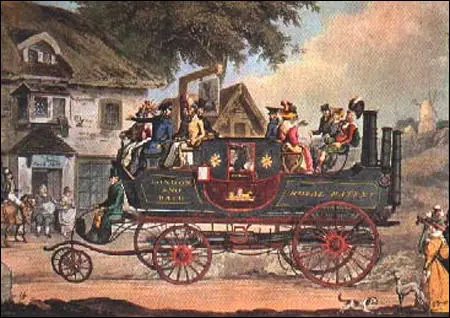

On its trips between London and Bath it reached an average speed of 15 m.p.h.

Metcalf's next major contract was a 6 mile stretch between Harrogate and Harewood, near Leeds, for which he received £1200. As Metcalf's reputation grew he was awarded contracts in other parts of Yorkshire and, subsequently, in Lancashire, Derbyshire, and Cheshire. A contemporary noted that Metcalf was "a projector and surveyor of highways in difficult and mountainous parts" using only his staff as a guide. (9) According to Samuel Smiles, he sometimes got jobs because he kept his blindness from the people who gave out the contracts. (10)

This road was so successful he was commissioned to build a series of roads that were able to carry heavy wagons and withstand wet weather. According to Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) "Metcalf used rafts to build roads across bogs and was an astute surveyor, able to calculate materials and costs accurately. He went on building roads across the north of England, giving manufacturers and commercial travellers easier access to markets and canal and ports." (11)

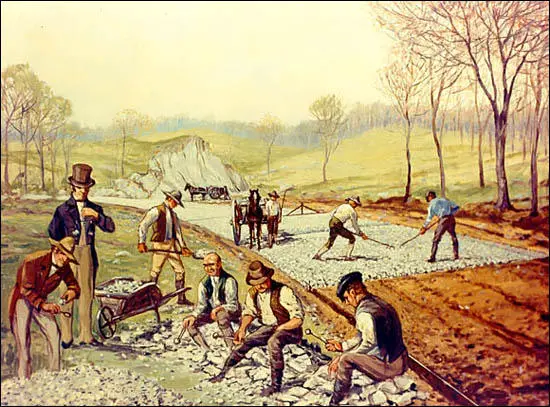

Another important road builder was Thomas Telford. This talented engineer adapted ideas first used by the Romans. On top of foundations made from large stone blocks, Telford spread layers of large and small stones. Telford's method was based on the idea that vehicles could assist rather than destroy roads. He pointed out that by using small stones on the surface of the road, the more traffic that used the road, the more tightly compacted the stones would become. Telford's roads were very impressive, but they were also expensive and the Turnpike companies found it difficult to make profits from this method of road building. (12)

Eventually another Scottish engineer, John Macadam, came up with a cheaper method of making good roads. As he explained later: "I have generally made roads three inches higher in the centre than I have at the sides... if the road be smooth and well made, the water will run easily on such a slope... I always make my surveyors carry a pair of scales and a six ounce weight in their pocket and when they come to a heap of stones, they weigh one or two of the largest". (13)

In 1816, Macadam was employed by the Bristol Turnpike Trust. Macadam developed the view that roads did not need stone foundations. His method was to spread a series of thin layers of small angular stones over a subsoil base. After each layer was laid, it was left for a while so that the weight of vehicles using the road could compact the stones together. These 'macadamized' roads enabled horses to pull three times the load they could on other road surfaces. Wagons and coaches could also travel much faster on this surface. (14)

Primary Sources

(1) Pehr Kalm from Sweden travelled through England in 1748.

In Sweden the road is higher than the land around, but here exactly the opposite is the case... In this country very large wagons are used with many horses... Through many years' driving, the wagons seem to have eaten down into the ground... to a depth of two, four, or six feet.

(2) John Macadam, evidence to Parliamentary Committee (1819)

I have generally made roads three inches higher in the centre than I have at the sides... if the road be smooth and well made, the water will run easily on such a slope... I always make my surveyors carry a pair of scales and a six ounce weight in their pocket and when they come to a heap of stones, they weigh one or two of the largest.

(3) Advertisement for the Manchester flying-coach in 1754.

However, incredible it may appear, this coach will actually (barring accidents) arrive in London four days and a half after leaving Manchester.

(4) John Copeland, Roads and their Traffic: 1750-1850 (1968)

Light, well-sprung vans were able to travel faster than the old cumbersome wagons. Pickford's started using these vans in 1814-15, the journey from Manchester to London taking thirty-six hours.

(5) George Walker, The Costume of Yorkshire (1814)

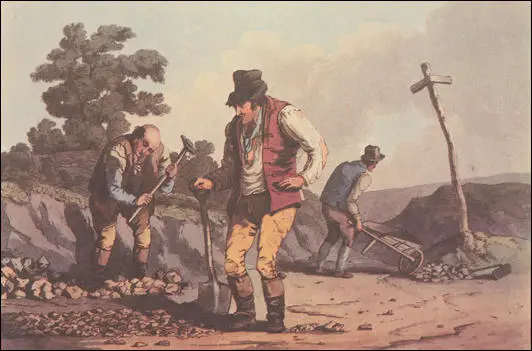

As gravel is not in general plentiful, except on the coast, the roads in Yorkshire are usually made of stone, which abounds in almost every part of the county. It is brought in large pieces from the quarry, and thrown from the carts on the road side, at convenient distances, where repair is necessary. Men are employed afterwards to break it, and spread it... In times however like these, when machinery is applied with profit and advantage to almost every purpose of agriculture and trade, it must be a matter of surprise that no machines have yet been invented and used for breaking stone for the road ; they would not only improve the roads, but be a great saving of time, trouble, and expense.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)