Johannes Fest

Johannes Fest, was born in Kreis Samter on 6th February, 1898. A talented student he became a teacher. He served in the First World War but was wounded on the Western Front and returned to teaching. (1)

After the war he became head teacher of the Twentieth Elementary School, He took a keen interest in politics and had been a member of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP). A strong opponent of Adolf Hitler he was a senior figure in the Reichsbanner. (2)

Johannes Fest married Elisabeth Straeter and she gave birth to Joachim Fest, Winfried, Hannif, Wolfgang, and Christa. Neal Ascherson, has pointed out: "He (Johannes Fest) dominated his family, an imperious patriarch given to terrific rages at the dining-table but unbending in his attachment to straightness, good behaviour and democracy. His four principles were militant republicanism (he had detested the kaiser), Prussian virtue (taken with a spice of irony), the Catholic faith and German high culture as inherited by the educated middle class." (3)

His children adored him: "One of his friends once said that my father was a rare combination of energy, self-confidence, and mirth. His sharp wit could even turn into high spirits. Friends of my own youth whom I asked for the impression they had of him when they looked back, often said that as children there was hardly another adult whom they so enjoyed being with, because he was able to tell such crazy stories and sing such silly songs. Almost all spoke in these or similar terms of his ability to entertain and his enjoyment of practical jokes. Admittedly, he sometimes suffered from a short temper; that may have been because his good humor did not come from an inner balance alone, but also had something to do with the certainty of being able to deal with all the trials of fate." (4)

Johannes Fest was friends with several politicians including Max Fechner, a Social Democratic Party (SDP) activist, Franz Künstler, chairman of the Berlin SDP, and Heinrich Krone (BVP). However, he was a strong opponent of Ernst Thalmann, the leader of the German Communist Party (KPD).

Johannes Fest and Adolf Hitler

Soon after Adolf Hitler took power Johannes Fest "was twice summoned to the local education authority, and later to the ministry, and questioned on his attitude towards the Government." On his return from the third meeting he told his wife, Elisabeth Straeter Fest, that he refused to back down and described the new government as a "rabble". She replied: "You know that I have always supported you in what you believe to be right. I always will. But have you thought of the children and what your obstinacy could mean for them?" On 20th April, 1933, was suspended from his post. (5)

Rachel Seiffert has claimed: "From 1933 until the end of the war, this intelligent and energetic man was reduced to an observer, watching the gradual erosion of civil society around him, first with incredulity and then with horror. He concentrated his efforts on his immediate circle, urging Jewish friends to leave." (6)

Johannes Fest was close to Dr. Goldschmidt, a Jewish lawyer. After the passing of the Nuremberg Laws Johannes Fest urged him to leave Germany: "But, Dr. Goldschmidt, who, as a German patriot, had always felt it his duty to drink only German red wine instead of the far superior French and to buy only German clothes, shoes, and groceries, had paid no heed. Germany, said Dr. Goldschmidt, was a state of law; it was in people's bones, so to speak." He later died in an extermination camp. (7)

In 1935 Joachim Fest recalled hearing a row in which his mother pleaded with his father to become a member of the Nazi Party, arguing that a little hypocrisy was justified to ease the hardship the family was undergoing. "Everyone else might join, but not me... We are not little people in such matters." He used to quote the Latin maxim: "Even if others do - I do not!" Joachim later recalled seeing him come home covered in blood after fighting street battles with the Sturmabteilung (SA). (8)

The family could no longer afford servants and they all had to leave. The main loss was the nursemaid, Franziska, who according to Joachim was "after our mother, she was the dearest person to us". The children also had to make sacrifices: "There were no toys anymore and Wolfgang did not get his remote-controlled Mercedes Silver Arrow model racing car or I the football... The model railway already lacked gates, bridges, and points, so to make any progress at all we built hills out of papier-mache on which we placed home-made houses, churches, and towers." (9)

There were several visits from the Gestapo. "The men in belted leather coats who came from time to time and with a Heil Hitler! entered the apartment without waiting to be invited were more than enough to create a threatening atmosphere. Without another word they shut themselves in the study with my father, while my mother stood in front of the coat recess, her face rigid." (10)

By 1936 Wolfgang and Joachim Fest became old enough to join the Hitler Youth. However, his father refused to allow the boys to join the organisation. Despite this, Fest never joined any resistance group and did nothing active to damage the Nazi dictatorship, but refused to abandon his Jewish friends until they were sent to concentration camps. (11)

In February, 1938, Adolf Hitler invited Kurt von Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor, to meet him at the Berghof. Hitler demanded concessions for the Austrian Nazi Party. Schuschnigg refused and after resigning was replaced by Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the leader of the Austrian Nazi Party. On 13th March, Seyss-Inquart invited the German Army to occupy Austria and proclaimed union with Germany. (12)

In his autobiography, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006), Joachim Fest, pointed out that his father had mixed feelings about the Anschluss: "In March 1938... German troops crossed the border into Austria under billowing flags and crowds lined the streets cheering and throwing flowers. Sitting by the wireless we heard the shouted Heil!s, the songs and the rattle of the tanks, while the commentator talked about the craning necks of the jubilant women, some of whom even fainted. It was yet another blow for the opponents of the regime, although my father, like Catholics in general, and the overwhelming majority of Germans and Austrians, thought in terms of a greater Germany, that is, of Germany and Austria as one nation. For a long time he sat with the family in front of the big Saba radio, lost in thought, while in the background a Beethoven symphony played. Why does Hitler succeed in almost everything? he pondered. Yet a feeling of satisfaction predominated, although once again he was indignant at the former victorious powers." (13)

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

Ernst vom Rath was murdered by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish refugee in Paris on 9th November, 1938. At a meeting of Nazi Party leaders that evening, Joseph Goebbels suggested that night there should be "spontaneous" anti-Jewish riots. (14) Reinhard Heydrich sent urgent guidelines to all police headquarters suggesting how they could start these disturbances. He ordered the destruction of all Jewish places of worship in Germany. Heydrich also gave instructions that the police should not interfere with demonstrations and surrounding buildings must not be damaged when burning synagogues. (15)

Joseph Goebbels wrote an article for the Völkischer Beobachter where he claimed that Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) was a spontaneous outbreak of feeling: "The outbreak of fury by the people on the night of November 9-10 shows the patience of the German people has now been exhausted. It was neither organized nor prepared but it broke out spontaneously." (16) However, Erich Dressler, who had taken part in the riots, was disappointed by the lack of passion displayed that night: "One thing seriously perturbed me. All these measures had to be ordered from above. There was no sign of healthy indignation or rage amongst the average Germans. It is undoubtedly a commendable German virtue to keep one's feelings under control and not just to hit out as one pleases; but where the guilt of the Jews for this cowardly murder was obvious and proved, the people might well have shown a little more spirit." (17)

Johannes Fest visited Berlin the following morning: "On November 9, 1938, the rulers of Germany organized what came to be known as Kristallnacht, and showed the world, as my father put it, after all the masquerades, their true face. The next morning he went to the city center and afterward told us about the devastation: burnt-out synagogues and smashed shop windows, the broken glass everywhere on the pavements, the paper blown in the wind, and the scraps of cloth and other rubbish in the streets. After that he called a number of friends and advised them to get out as soon as possible." (18)

Joachim Fest later pointed out that Kristallnacht had an impact on Jewish children at his school: "It was at this time that, without notice, the only Jewish pupil in our class stopped coming. He was quiet, almost introverted, and usually stood a little aside from the rest, but I sometimes asked myself whether he always appeared so unfriendly because he feared being rejected by his schoolmates. We were still puzzling over his departure, which had occurred without a word of farewell... As a Jew he would soon not be allowed to go to school anyway. Now his family had the chance to emigrate to England. They didn't want to miss the chance." (19)

The Second World War

Joachim Fest attended Leibniz Gymnasium. In January 1941 he had used his pocketknife to carve out a caricature of Hitler on a school desk. One of the boys who was a keen member of the Hitler Youth told his teacher about what he had done. "I denied any kind of political motive, but admitted the damage to property and asked to be shown leniency." This was rejected and he was expelled from the school. Johannes Fest was told: "It would be best if you took your other two sons (Winfried and Wolfgang) away at the same time!" (20)

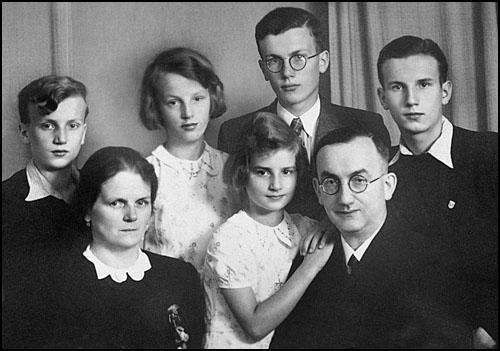

Front row: Elisabeth, Christa and Johannes Fest (1941)

In February 1941, Nazi Party officials arrived at the house and pointed out that none of his three sons had joined either the junior Jungvolk or the Hitler Youth. Johannes Fest sent them away: "Whoever you are. I have no intention of allowing you to come here, on a Sunday at that... Because we have several times been pestered, likewise on a Sunday morning, by your lads. So you haven't just found out something. And now, will you leave my house? Get out! This minute!" His wife told him: "This time you've gone too far!" However, much to his surprise, they did not return. (21)

Johannes Fest, aged 46, was conscripted into service. At first he was assigned to a unit building tank obstacles. (22) In July 1944, Joachim Fest volunteered to join the German Army. His father objected to him joining "Hitler's criminal war". He replied that he did this to avoid being conscripted into the Waffen SS . (23) In October he was transferred to a small town on the Lower Rhine: "There we were trained in duties as sappers, in building pontoons and in moving bridges." Soon afterwards he discovered this his brother Wolfgang had died while serving in Silesia. (24)

Johannes was captured by the Red Army. Whereas his son, Joachim, was taken by the United States Army. The two men were reunited after the war. "He was hardly recognizable: a man abruptly grown smaller, slighter, gray-haired. Most of the time he simply sat there, his eyes sunken, where previously he had always set the tone. After repeated questions, he talked - as if he had to dredge his memory - of the shellfire that had poured down onto Konigsberg in the final days before its surrender; of the flamethrowers; of the terrible stench of corpses in the ruins, which continued to spoil his sense of smell." (25)

Johannes Fest returned to work and became a member of the district school board in Berlin-Tempelhof. He joined the Christian Democratic Union of Germany and from 1950 to 1958 he represented them in the Abgeordnetenhaus. After his retirement from the House of Representatives he was a district councilor in Neukölln.

Johannes Fest died in Berlin on 15th September 1960.

Primary Sources

(1) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

He (Johannes Fest) was a tall man with strong features; the "telegenic face" (as Wolfgang and I called it) which he displays in most pictures reveals only sternness and determination, without giving any clue to the cheerful character and even happiness that comes when a person is in harmony with himself. One of his friends once said that my father was a rare combination of energy, self-confidence, and mirth. His sharp wit could even turn into high spirits. Friends of my own youth whom I asked for the impression they had of him when they looked back, often said that as children there was hardly another adult whom they so enjoyed being with, because he was able to tell such crazy stories and sing such silly songs. Almost all spoke in these or similar terms of his ability to entertain and his enjoyment of practical jokes. Admittedly, he sometimes suffered from a short temper; that may have been because his good humor did not come from an inner balance alone, but also had something to do with the certainty of being able to deal with all the trials of fate.It should also be said that my father did not have the least touch of social snobbery and could chat as easily to the girl behind the counter at the baker's as discuss serious affairs of state with a senior civil servant. He was as relaxed with a university teacher as with the children at our birthdays... He liked to laugh and could entertain a company at table all evening with witty anecdotes or - if it was required - more down-to-earth ones.

His origin, life, and strong convictions conferred on my father four qualities, none of which seemed to go with the others and each of which developed an impatience with the other three. He was a republican, a Prussian, a Catholic, and a Bildungsburger. In his case, however, all contradictions were held together by strength of personality and each one of these strands contributed to his intransigence.

(2) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

One Sunday at the beginning of February 1941, shortly after we had come back from church, two senior Hitler Youth officials entered the building, banging the street door and demanding to speak to my father. They had just found out-one of them shouted from the bottom of the stairs-that none of his three sons had joined either the junior Jungvolk or the Hitler Youth. There had to be an end to it. "Malingering!" barked the other. "Impertinence! How dare you!" Everybody had duties. "You, too!" the first one joined in again.My father had, meanwhile, gone down to the pair. "Whoever you are," he responded, frowning in annoyance, "I have no intention of allowing you to come here, on a Sunday at that, with a lie. Because we have several times been pestered, likewise on a Sunday morning, by your lads. So you haven't just found out something." And getting ever louder, he finally roared at them, "You accuse me of malingering and are yourself cowards!" And after a few more rebukes he shouted from the second step over their army-style cropped heads, "And now, will you leave my house? Get out! This minute!" The pair seemed speechless at the tone my father dared to use, but before they could reply he drove them back, so to speak, through the entrance lobby and out the door. The commotion had initially startled the whole building, and several tenants had appeared on the stairs. At the sight of the uniforms, however, they quietly closed the doors to their apartments.

Hardly had the street door closed behind the two Hitler Youth leaders when my father raced up the stairs to calm my mother. She was standing in the door as if paralyzed and only said, "This time you've gone too far!" My father put his arm around her and admitted he had forgotten himself for a moment. But first the Nazis had stolen his profession and his income, now they were attacking his sons and Sunday itself One had to show these people that there was a limit. "They know none," said my mother in an expressionless voice. It was all the more important, objected my father, to point it out to them.

(3) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

To be right when everybody else has been wrong can be a lonely, even disabling experience. This may be a way of understanding the enigmatic character of Joachim Fest, the German historian, journalist and editor who died six years ago. His Berlin family belonged to the Bildungsbürgertum - roughly, the well-educated middle class - and rejected Hitler and National Socialism from the very first moment. They were not part of any resistance group; they did nothing ‘active’ to damage the Nazi dictatorship. They simply refused to let this dirty, vulgar, evil thing across the threshold until, in the final stages of the war, it broke in and took their sons and their father away to defend the collapsing Reich. For their defiance – refusing to join the Hitler Youth or League of German Maidens voluntarily, refusing to abandon their Jewish friends until they ‘disappeared’ - the father lost his job as a headmaster and was banned from all employment. The family was repeatedly threatened by the Gestapo and denounced by its neighbours. They were lucky nothing worse happened to them...It was the matter of postwar guilt which isolated him. His family was exceptional because it had no reason to apologize for National Socialism, although his father, especially, felt searing shame for his country. Fest clearly found the cult of guilt unconvincing. If you looked more closely, he believed, you could see that the penitent was almost always blaming other people – his neighbours, his nation collectively – and never himself. There was a silent consensus not to stare into the bathroom mirror in the search for causes. The mood was rather: "Yes, we admit that Germany under that criminal regime was guilty; now let’s move on." But Fest, because he was genuinely not guilty, couldn’t play this game. "Unlike the overwhelming majority of Germans, we were not part of some mass conversion … we were excluded from this psychodrama. We had the dubious advantage of remaining exactly who we had always been, and so of once again being the odd ones out." So, too, did quite a few survivors of the sacrificial plots against Hitler. Everyone was respectful to them (unless they had been communists) and gave them medals. But in the Bonn republic they were decorated strangers, with a space around them.

(4) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)

Fest's parents were devout Catholics, proudly Prussian, and had been ardent supporters of the Weimar Republic. Regarding both communists and Nazis with deep distrust, they kept company with like-minded political activists and intellectual Catholic clergy, and had many close Jewish friends.

Great weight was given to learning in this circle, and Fest marks the stages of his formative years by the books he was given to read. At his boarding school in Freiburg, southern Germany, he buried himself in Schiller's Wallenstein "throughout the autumn and early winter of the Russian campaign, so that for me, Freiburg is forever associated with Schiller and as an absurd contrast to the ice storms and blizzards outside Moscow".

Immersed in both high culture and current events, the young Fest was also taken seriously by the adults who passed through his household. This was evidently stimulating for a quick and developing mind, and perhaps also established the intellectual certainty that so marked him out in adulthood. After Fest made clear to his headmaster how parochial he thought him, his fellow pupils asked: "Have you no manners?" "I certainly did, I retorted, but only where there was mutual respect."

The author's bone-dry humour is evident throughout the memoir. It emerges as just one of the many defences the family had to cultivate to endure the Nazi era. They lived with poverty, social exclusion, and under constant threat of visits from the Gestapo, but Fest doesn't take the moral high ground. If ever a book demonstrated the slow but seemingly unstoppable reach of tyranny, even into the private realm, it is this one. He shows how tempting compromise becomes, even while it remains loathsome, and bears witness to the cost and limits of individual courage.

His memories of his father are particularly affecting in this regard. Johannes Fest was a school teacher, whose repeated refusal to join the Nazi party led to him being banned from employment. From 1933 until the end of the war, this intelligent and energetic man was reduced to an observer, watching the gradual erosion of civil society around him, first with incredulity and then with horror. He concentrated his efforts on his immediate circle, urging Jewish friends to leave, and seeing off the Hitler Youth who came calling to forcibly recruit his sons.

Fest absorbed his father's scathing view of the regime, scratching caricatures of Hitler on to his school desk. At the meeting that confirmed his subsequent expulsion, Fest's father put his arms about him – a rare and bravely public show of approbation. His blessing was not easily won. Of Fest's chosen field, his father said the Third Reich was "no more than a gutter subject. Hitler's supporters came from the gutter and that's where they belonged. Historians like myself were giving them a historical dignity to which they were not entitled".

Fest senior learnt of the developing Holocaust through friends, and his sense of impotence must have been intolerable; it certainly left its scars. When his sons entreated him to write about his experiences after the war, he responded: "I did not want to talk about it then, and I do not want to now. It reminds me that there was absolutely nothing I could do with my knowledge." While others accepted requisitioned villas in leafy suburbs from the Allies, Fest senior refused. "For compensation, my father had only the knowledge of meeting his own rigorous principles."

(5) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

At his father's insistence, Fest did not join the Hitler Youth, but in 1944 volunteered for the army to avoid conscription into the Waffen-SS. Johannes maintained that "one does not volunteer for Hitler's criminal war" and that conscription was preferable; after spending time as a PoW in France, Joachim revisited the subject with his father: "You weren't wrong," the older man allowed him, "But I was the one who was right."

His father's integrity became the standard Fest used to measure the psychological weakness and moral prevarications of his countrymen in a lifelong quest to explain how they could have descended into the madness of the Holocaust. His profiles of prominent Nazis in The Face of the Third Reich (1963), his first success and a groundbreaking work for that time, could have come straight from the pages of Dostoevsky as Fest probes in scintillating style the dysfunctional psyches, personal ambitions, contradictions and self-serving delusions of the men who helped create the Third Reich, while showing how they embodied the attitudes of their classes. Hitler (1973) broke new ground by focusing on a psychological exploration of the Nazi leader who, Fest said, operated like "a reptile", outside established moral norms.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 16

(2) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 17

(3) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(4) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 18

(5) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 46

(6) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)

(7) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 86

(8) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

(9) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 52

(10) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 55

(11) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(12) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) pages 425-429

(13) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 118

(14) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987) page 67

(15) Reinhard Heydrich, instructions for measures against Jews (10th November, 1938)

(16) Joseph Goebbels, article in the Völkischer Beobachter (12th November, 1938)

(17) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011) page 66

(18) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 123

(19) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 125

(20) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 174

(21) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 177

(22) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 258

(23) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

(24) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) pages 268-271

(25) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) pages 357