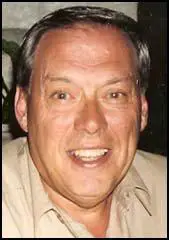

Alfred C. Baldwin III

Alfred Carleton Baldwin III was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on 23rd June, 1936. His father was a lawyer and a state unemployment compensation commissioner. He graduated from Fairfield University in 1957 with a BBA then entered the United States Marines.

In 1960 Baldwin entered the University of Connecticut, School of Law. After graduating in 1963 he joined the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Memphis and was soon afterwards sent to Tampa. Later he was assigned as the Resident Agent for Sarasota, Florida with the responsibility for four counties on the west coast area of Florida.

Alfred Baldwin resigned from the FBI in 1966 and worked as the Director of Security for a multi-state trucking firm. He left this position to work for a retired Naval Admiral who was creating a college degree program at the University of New Haven for law enforcement personnel who desired a college degree in the police administration and law enforcement field.

Alfred Badwin was living in New Haven when he was recruited by James W. McCord in May, 1972, to work for the Committee to Re-elect the President. His first job was to work as a bodyguard for Martha Mitchell, the wife of John Mitchell, who was living in Washington. According to McCord's testimony he selected Baldwin's name from a registry published by the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI. As Jim Hougan, the author of Secret Agenda (1984) pointed out, this was a strange decision because despite hundreds of FBI retirees in the Washington area, McCord selected a man living in Connecticut. Hougan speculates that "Baldwin was somehow special and perhaps well known to McCord".

Baldwin accompanied Martha Mitchell to Chicago. Mitchell did not like Baldwin and described him as the "gauchest character I've ever met". Baldwin was then replaced by another security man. Baldwin was later to question this description of him. "I was later told that it was due to the fact that I had attended a cocktail party and had taken my shoes and socks off and had placed my bare feet on a cocktail table in front one of the President's cabinet members, I believe the Secretary of Transportation Volpe. This was totally false and I was willing to take a lie detector test to prove that I had never ever been in the presence of any cabinet member."

On 11th May, 1972, McCord arranged for Baldwin to stay at Howard Johnson's motel, across the street from the Watergate complex. The room 419 was booked in the name of McCord’s company. McCord had been asked by Gordon Liddy and E.Howard Hunt to place electronic devices in the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. The plan was to wiretap the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee. On 28th May, 1972, McCord and his team broke into the DNC's offices and placed bugs in two of the telephones.

It became Baldwin’s job to eavesdrop the phone calls. Over the next 20 days Baldwin listened to over 200 phone calls. These were not recorded. Baldwin made notes and typed up summaries. Nor did Baldwin listen to all phone calls coming in. For example, he took his meals outside his room. Any phone calls taking place at this time would have been missed.

It soon became clear that the bug on one of the phones installed by James W. McCord was not working. As a result of the defective bug, McCord decided that they would have to break-in to the Watergate office again. He also heard that a representative of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War had a desk at the DNC. McCord argued that it was worth going in to see what they could discover about the anti-war activist. Gordon Liddy later claimed that the real reason for the second break-in was "to find out what O’Brien had of a derogatory nature about us, not for us to get something on him.”

On 17th June, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord returned to O'Brien's office. It was Baldwin's job to observe the operation from his hotel room. When he saw the police walking up the stairwell steps he radioed a warning. However, Barker had turned off his walkie-talkie and Baldwin was unable to make contact with the burglars.

When E.Howard Hunt arrived at Baldwin’s hotel room he made a phone call to Douglas Caddy, a lawyer who had worked with him at Mullen Company (a CIA front organization). Baldwin heard him discussing money, bail and bonds. Hunt then told Baldwin to load McCord’s van with the listening post equipment and the Gemstone file and drive it to McCord’s house in Rockville.

Baldwin told his story to a lawyer to a friend and classmate at law school, Robert Mirto. This information was eventually passed to John Cassidento, a strong supporter of the Democratic Party. He did not tell the authorities but did pass this information onto Larry O’Brien. The Democrats now knew that people like E.Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy were involved in the Watergate break-in.

As Edward Jay Epstein has pointed out: "By checking through the records of phone calls made from this listening post, the FBI easily located Alfred Baldwin, a former FBI agent, who had kept logs of wiretaps for the conspirators and acted as a look-out." On 25th June, Baldwin agreed to cooperate in order to avoid the grand-jury looking into the case.

Robert Mirto and John Cassidento also arranged for Baldwin to talk to the press. He was interviewed by Jack Nelson and the article was published in the Los Angeles Times on 4th October, 1972. According to Katharine Q. Seelye in the New York Times, "The account was among the first in which the public learned details of the break-in, including that the one in June, in which the burglars were caught, was their second visit to the offices of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate."

After Watergate, Mr. Baldwin struggled to find work. In 1974 he landed a job as a substitute teacher in New Haven. He received a master's degree in education from Southern Connecticut State Universit. And though he had received his law degree two decades earlier, he took the bar exam for the first time in 1987 and passed. He also served as an Assistant State Attorney Prosecutor (1986 to 1996). Baldwin retired in 1996 and lived in Vero Beach, Florida.

Alfred Carleton Baldwin III died of cancer on 15th January, 2020 in New Paltz, N.Y.

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Jay Epstein, Did the Press Uncover Watergate? (July, 1974)

A sustaining myth of journalism holds that every great government scandal is revealed through the work of enterprising reporters who by one means or another pierce the official veil of secrecy. The role that government institutions themselves play in exposing official misconduct and corruption therefore tends to be seriously neglected, if not wholly ignored, in the press. This view of journalistic revelation is propagated by the press even in cases where journalists have had palpably little to do with the discovery of corruption. Pulitzer Prizes were thus awarded this year to the Wall Street journal for "revealing" the scandal which forced Vice President Agnew to resign and to the Washington Star/News for "revealing" the campaign contribution that led to the indictments of former cabinet officers Maurice Starts and John N. Mitchell, although reporters at neither newspaper in actual fact had anything to do with uncovering the scandals. In the former case, the U.S. Attorney in Maryland had through dogged plea-bargaining and grants of immunity induced witnesses to implicate the Vice President; and in the latter case, the Securities and Exchange Commission and a grand jury had conducted the investigation that unearthed the illegal contribution which led to the indictment of the cabinet officers. In both instances, even without "leaks" to the newspapers, the scandals uncovered by government institutions would have come to the public's attention when the cases came to trial. Yet to perpetuate the myth that the members of the press were the prime movers in such great events as the conviction of a Vice President and the indictment of two former cabinet officers, the Pulitzer Prize committee simply chose the news stories nearest to these events and awarded them its honors.

The natural tendency of journalists to magnify the role of the press in great scandals is perhaps best illustrated by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward's autobiographical account of how they "revealed" the Watergate scandals. The dust jacket and national advertisements, very much in the bravado spirit of the book itself, declare: "All America knows about Watergate. Here, for the first time, is the story of how we know.... In what must be the most devastating political detective story of the century, the two young Washington Post reporters whose brilliant investigative journalism smashed the Watergate scandal wide open tell the whole behind-the-scenes drama the way it happened." In keeping with the mythic view of journalism, however, the book never describes the "behind-the-scenes" investigations which actually "smashed the Watergate scandal wide open"-namely the investigations conducted by the FBI, the federal prosecutors, the grand jury, and the Congressional committees. The work of almost all those institutions, which unearthed and developed all the actual evidence and disclosures of Watergate, is systematically ignored or minimized by Bernstein and Woodward. Instead, they simply focus on those parts of the prosecutors' case, the grand-jury investigation, and the FBI reports that were leaked to them.

The result is that no one interested in "how we know" about Watergate will find out from their book, or any of the other widely circulated mythopoeics about Watergate. Yet the non-journalistic version of how Watergate was uncovered is not exactly a secret-,the government prosecutors (Earl Silbert, Seymour Glanzer, and Donald E. Campbell) are more than willing to give a documented account of the investigation to anyone who desires it. According to one of the prosecutors, however, "No one really wants to know." Thus the government's investigation of itself has become a missing link in the story of the Watergate scandal, and the actual role that journalists played remains ill understood.

After five burglars, including James McCord, who was an employee of the Committee for the Re-election of the President (CRP), were arrested in the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate complex on June 17, 1972, the FBI immediately located three important chains of evidence. First, within a week of the break-in, hundred-dollar bills found on the burglars were easily traced by their serial numbers through the Federal Reserve Bank at Atlanta to the Miami bank account of Bernard Barker, one of the burglars arrested in the Watergate. By June 22, the prosecutors had subpoenaed Barker's bank transactions, and had established that the hundred-dollar bills found in the burglary had originally come from contributions to the Committee for the Re- election of the President and specifically from checks deposited by Kenneth Dahlberg, a CRP regional finance chairman, and others. (Copies of these checks were leaked to Woodward and Bernstein by an investigator for the Florida state's attorney one month later, well after the grand jury was presented with this information-and they "revealed" it in the Washington Post on August 1.) And in early June, the treasurer of the Republican National Committee, Hugh W. Sloan, Jr., confirmed to the prosecutors that campaign contributions were given to G. Gordon Liddy, who by then was suspected of being the ringleader of the conspiracy.

Secondly, the FBI, in searching the premises of the burglars, found, within twenty-four hours after their arrest, receipts, address-books, and checks that linked E. Howard Hunt, White House consultant, to the conspiracy. (This information was leaked a few days later by the Washington police to Eugene Bachinski, a Washington Post reporter, and subsequently published in that newspaper.) The investigation into Hunt led the prosecutors to his secretary, Kathleen Chenow, who was flown back from England, and, in early July, confirmed that Hunt and Liddy were working on clandestine projects together, and had had telephone calls from Bernard Barker just before Barker was arrested in Watergate. (Months later, in September, defense attorneys who had been given the list of prosecution witnesses leaked Miss Chenow's name to Woodward and Bernstein, who then-after calling her-"revealed" this information to the public.) Thus, in early July, the prosecutors had presented evidence to the grand jury tying Hunt and Liddy to the burglars (as well as Liddy to the money).

The most important chain of evidence involved an eyewitness to the entire conspiracy. The day of the burglary, the FBI discovered a listening post at the Howard Johnson Motor Hotel, across the street from the Watergate, from which conspirators sent radio signals to the burglars inside Watergate (and received transmissions from electronic eavesdropping devices). By checking through the records of phone calls made from this listening post, the FBI easily located Alfred Baldwin, a former FBI agent, who had kept logs of wiretaps for the conspirators and acted as a look-out. By June 25, after the prosecutors offered Baldwin's attorney a deal by which Baldwin could escape prison, Baldwin agreed to cooperate with the government.

The main instrument for extracting information from reluctant witnesses like Baldwin was the prosecutors' skill in threatening, badgering, and negotiating. By July 5, less than three weeks after the burglars were apprehended, Baldwin sketched out the outlines of the conspiracy. He identified Hunt and Liddy as being at the scene and directing the burglary; he described prior break-in attempts, the installation of eavesdropping devices, the monitoring of logs of the eavesdropping, and the delivery of the fruits of the conspiracy to CRP. All this evidence was of course presented to the grand jury in mid-July. (Liddy's name was only mentioned in passing in the press on July 22, when he resigned from CRP, and it was not until the following October that Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times located and published an interview with Baldwin. To "top" the L.A. Times's interview, Woodward and Bernstein erroneously reported that Baldwin had delivered the logs to three executives at CRP, Robert C. Odle, Jr., Glenn J. Sedam, Jr., and William E. Timmons. In fact, Baldwin delivered the logs to Liddy. In any case, the press was three months behind the prosecutors in disclosing Baldwin's vital account.) The prosecutors needed, however, a witness to corroborate Baldwin, since they realized that any single witness could be discredited by fierce cross-examination. The locating of Thomas J. Gregory, a student working as a minor spy for CRP, was critical for the prosecutors' case since he was able to corroborate important elements in Baldwin's account. (Gregory's existence was never mentioned by the press until the trial.)

The prosecutors and the grand jury thus developed an airtight case against Liddy, Hunt, and the five burglars well in advance of, and without any assistance from, Woodward, Bernstein, or any other reporters. The case was presented to the grand jury and would certainly have been made public in the trial. At best, reporters, including Woodward and Bernstein, only leaked elements of the prosecutors' case to the public in advance of the trial.

(2) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, All the President's Men (1974)

The night of October 4, Woodward got home at about eleven. The phone was ringing as he stepped in the door. "Ace-" it was Bill Brady. The night editor calls all. the young reporters "Ace." (Brady had called Woodward "Ace" the second night he worked at the Post, and Woodward's. head had swelled for several hours, until he heard Brady address a notorious office incompetent by the same title.)

"Ace," said Brady, "the L.A. Times is running some long interview with a fellow named Baldwin." Woodward groaned, and said he'd be right in.

Alfred C. Baldwin III had seemed for a time to be one of the keys to Watergate.' The reporters had learned of him while making some routine checks. Bernstein had been told that a former FBI agent had participated in the Watergate operation; that he had informed investigators that Democratic headquarters had been under electronic surveillance for about three weeks before the arrests; and that memos of the wiretapped conversations had been transcribed and sent directly to CRP. The man had also said he had Infiltrated the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, on orders from McCord. On September 11, Bernstein and Woodward had written a story about the participation of such a former FBI agent. A week later, with help from the Bookkeeper, they had identified him as Baldwin, a 35-year-old law-school graduate who had worked as chief of security for a trucking firm before becoming a CRP employee paid in $100 bills. Baldwin was the government's chief witness-the insider who was spilling the whole story. He seemed to have unimaginable secrets to tell, and reporters were in line to hear - them. Woodward had joined the queue. He began making regular phone calls to Baldwin's lawyer, John Cassidento, a Democratic state legislator from New Haven, Connecticut.

(3) E.Howard Hunt, Undercover (1975)

On October 4 Chief Judge John J. Sirica issued an order enjoining everyone connected with the Watergate case from commenting publicly on it. Even so, the Los Angeles Times began publication of Al Baldwin's disclosures that he was McCord's monitor in the motel Listening Post and had himself delivered transcripts to the reelection committee prior to the unsuccessful entry. But despite Sirica's ruling, Baldwin's "memoirs" continued to be published by the Los Angeles Times.

As soon as I heard of Baldwin's declarations, I telephoned McCord and berated him for Baldwin's conduct. To my surprise, McCord defended Baldwin, saying that Baldwin, after consulting with attorneys in Connecticut immediately following his flight from Washington, had been advised to return to Washington and consult with CREP attorneys. According to McCord, Baldwin had done so, but had been turned away by the attorneys, who professed ignorance of his affairs, much less his involvement with James McCord. This reaction, McCord maintained, freed Baldwin to act independently of the rest of us, and this he had done. McCord then said he was feeling a monetary pinch and wondered when financial aid would be forthcoming. I told him that inasmuch as Baldwin had violated my orders and taken the van to McCord's home, the van-which McCord had purchased with money given him by Gordon Liddy-could be sold and the proceeds used for McCord's benefit. In closing, however, I remarked that I felt sure we would not be forgotten.

At this point I did not know McCord had charted an independent course of his own: He had been writing mysterious and Aesopian letters to a friend in CIA's Office of Security, and on October 10 McCord telephoned the Chilean Embassy. He identified himself as a Watergate defendant and requested a visa. McCord's assumption was that the embassy's phones were tapped and that when he filed a motion for government disclosure of any wiretaps on his line, the government would drop its case against him rather than reveal that the Chilean Embassy phone was tapped. This the government later denied.

From the first, my wife told me that her dealings with McCord made her feel uneasy. There was something "wrong" about him, she said repeatedly, and the less she had to do with him, the better, as far as she was concerned.

(4) Gail Russell Chaddock, Christian Science Monitor (7th June, 2005)

One reason is the protection that journalists may give to sources in exchange for information. That protection can compromise coverage. Deep Throat, for example, "seemed to know everything that the FBI had uncovered, but revealed nothing that cast the bureau in a poor light," writes Senate historian Ritchie in his latest book on the Washington press corps, "Reporting from Washington." (Ritchie correctly predicted that Deep Throat had a connection to the FBI.) It was the Los Angeles Times, not The Washington Post, that first reported the involvement of former FBI agent Alfred Baldwin in monitoring wiretaps for the Watergate burglars.

(5) Bernard L. Barker, Harper's Magazine (October, 1974)

McCord had the, highest rank of our group in jail then, and so we looked to him for leadership. But we didn't trust him totally, because McCord was very friendly with Alfred Baldwin, and to us; Baldwin was the first informer. To me, Baldwin represented the very lowest form of a human being. McCord was also different from the Cuban group because he did not know about the Ellsberg mission."

After the trial, we were waiting for the sentence in jail, and we were all under tremendous strain. And McCord told me one day: "Bernie, I am not going to jail for these people. If they think they are going to make a patsy out of me they better think again "

So I said, "Jimmy, you are probably a lot more intelligent than I am and you know a lot of things, but ' let's face it. In my way of thinking, you don't do this because of these people. You are going to have to live with McCord, and I am going to have to live with Barker. I don't do this because they are deserving or underserving, but because I have my own code."

Howard (Hunt) was very proud that we had stood up. We had played by the code and not broken. We took everything they had, and it was plenty. The judge sentenced me to forty-five years and the others to long terms, and he told us that our final sentence would be affected by what we told the grand jury and the Watergate Committee, by our cooperation. We were very worried, but we did not let out the Ellsberg thing. We were exposed by the very people who ordered us to do it without their even being in jail.

(6) Jim Hougan, Secret Agenda (1984)

Rental records at the Howard Johnson's, moreover, show that Room 419 was rented on May 5, six days before Baldwin's shift from the Roger Smith Hotel. If economizing was the purpose, McCord did not accomplish it with much efficiency - or why would he have retained Baldwin's redundant room at the Roger Smith? The truth, of course, is that McCord knew of the plans to break into the Watergate offices of the DNC. The Hojo (as it is affectionately known) was to serve as the operation's "listening post" - that is, as the site from which the bugging devices would be monitored. As such, the Hojo was ideal, having a clear view of both the Watergate and the Columbia Plaza Apartments down the street. There was nothing unusual, then, about moving Baldwin to the Howard Johnson's except, of course, for the timing and for the fact that his room was rented in the name of McCord's own firm, McCord Associates.

This was an inexcusable blunder, and it deserves comment. In his undercover work for McCord Associates, Baldwin would be required to use a series of aliases. The use of aliases was a standard precaution of tradecraft, a precaution taken in order to limit the damage in the event that any part of the operation was blown. Renting a room in the name of one's own firm while knowing that the room would be the headquarters of a felony in progress makes veteran intelligence agents suspicious of McCord's actual motives. The blunder, if that was what it was, was compounded even further by the fact that while resident at the Hojo, Baldwin received mail in his own name, entertained friends, and made long-distance calls to his mother and others on a regular basis. Each of those calls was a matter of record, and the FBI later found no difficulty at all in tracing them to Baldwin.

(7) William Shure, assistant minority counsel for Senate Watergate Committee, interviewed Alfred Baldwin on 30th March, 1973.

On May 23, Baldwin said, he returned to Connecticut and came back to Washington on Friday afternoon, the 26th. He had gone to Connecticut to get his own car at the instruction of McCord. He arrived back from Connecticut at approximately 1 p.m. and returned to his room, where he found McCord with all of the bugging equipment set up in the room. McCord very casually told Baldwin that after he had unpacked and showered and gotten organized, he, McCord, would explain to Baldwin what he [Baldwin] would be doing. Baldwin indicates that McCord was already attempting to listen to phone calls over the bugging devices and Baldwin was therefore convinced that a break-in of the Democratic headquarters had to have taken place prior to the 26th (of May). That afternoon McCord in fact showed Baldwin the equipment and McCord himself attempted to pick up conversations and did.

(8) Jim Hougan, Secret Agenda (1984)

In an earlier interview with the FBI, Baldwin told the same story (that the bugging started before 26th May), adding further details. "McCord was fiddling with... a Communication Electronics, Inc Receiving System.... During McCord's tuning of this instrument at 118.9 megacycles, a conversation was picked up to which Baldwin listened. The conversation was in regard to a man talking with a woman and discussing their marital problem." The same story, emphasizing the same date and the fact that the first telephone conversation was intercepted from Room 419 of the Howard Johnson's, was provided by Baldwin to the Los Angeles Times.

The implications of Baldwin's account are profound, and it is therefore worth emphasizing that his recollection of the matter has never varied in any significant detail. He recalls the circumstances perfectly, having just returned from Connecticut to find his motel room transformed into a miniature electronics studio. He recalls the nature of the conversation on which he came to eavesdrop, and is emphatic in his assertion that the event occurred in the afternoon of the twenty-sixth in Room 419. This last detail is important because on Monday morning, May 29, hours after the third and finally successful break-in, Baldwin shifted to a room on a higher floor of the Hojo in hopes of improving reception. Clearly, then, if the first interception occurred on a weekend afternoon prior to that move, the DNC had to have been bugged earlier than McCord and the others would have us believe.

In fact, however, all Baldwin knew was what McCord told him and whatever he might have surmised from the conversations of those on the line. He could not say from personal knowledge which telephone, in the DNC or elsewhere, had been bugged. Obviously, then, since the DNC was not broken into until May 29, and since Baldwin is emphatic about having monitored a telephone conversation on May 26, he must have been listening to the transmissions of a bug on a telephone in some location other than the DNC. On whom, then, was Baldwin eavesdropping?

(9) John J. Sirica, To Set the Record Straight (1979)

When we resumed for the third week, Baldwin was back on the stand. One fact that interested me in his testimony was that at one point he had personally delivered transcripts of the bugged phone conversations to the headquarters of the Committee to Re-elect the President. He told the court that he could not remember to whom he had delivered the transcript, and that aroused my suspicions. I asked the jury to leave the courtroom and addressed Baldwin: ". . . You stated that you received a telephone call from Mr. McCord in Miami in which I think the substance of your testimony was that as to one particular log he wanted you to put that in a manila envelope and staple it, and he gave you the name of the party to whom the material was to be delivered, correct?"

"Yes, Your Honor," Baldwin answered.

"You wrote the name of that party, correct?"

"Yes, I did," he said.

"On the envelope. You personally took that envelope to the Committee to Re-elect the President, correct?"

"Yes, I did," Baldwin said.

"What is the name of that party?" I asked. "I do not know, Your Honor," Baldwin said.

"When did you have a lapse of memory as to the name of that party?"

Baldwin said he simply couldn't remember the name even though the FBI had given him several names to test his recollection. He said he handed the envelope to a guard.

"Here you are, a former FBI agent, you knew this log was very important?" I asked.

"That is correct," Baldwin said.

"You want the jury to believe that you gave it to a guard, is that your testimony?" I asked. Every time the path led to the CRP, something happened to memories. We took a recess.

(10) John Simkin, Alfred C. Baldwin, International Education Forum (16th July, 2005)

One of the things that has always intrigued me is the large number of mistakes that were made during the Watergate operation. This is in direct contrast to other Nixon dirty tricks campaigns. Some people have speculated that there were individuals inside the operation who wanted to do harm to Nixon. I thought it might be a good idea to list these 24 “mistakes” to see if we can identify these individuals. Could it have been Bernard Barker?

(1) The money to pay for the Watergate operation came from CREEP. It would have been possible to have found a way of transferring this money to the Watergate burglars without it being traceable back to CREEP. For example, see how Tony Ulasewicz got his money from Nixon. As counsel for the Finance Committee to Re-Elect the President, Gordon Liddy, acquired two cheques that amounted to $114,000. This money came from an illegal U.S. corporate contribution laundered in Mexico and Dwayne Andreas, a Democrat who was a secret Nixon supporter. Liddy handed these cheques to E. Howard Hunt. He then gave these cheques to Bernard Barker who paid them into his own bank account. In this way it was possible to link Nixon with a Watergate burglar.

(2) On 22nd May, 1972, James McCord booked Alfred Baldwin and himself into the Howard Johnson Motor Inn opposite the Watergate building (room 419). The room was booked in the name of McCord’s company. During his stay in this room Baldwin made several long-distance phone calls to his parents. This information was later used during the trial of the Watergate burglars.

(3) On the eve of the first Watergate break-in the team had a meeting in the Howard Johnson Motor Inn’s Continental Room. The booking was made on the stationary of a Miami firm that included Bernard Barker among its directors. Again, this was easily traceable.

(4) In the first Watergate break-in the target was Larry O’Brien’s office. In fact, they actually entered the office of Spencer Oliver, the chairman of the association of Democratic state chairman. Two bugs were placed in two phones in order to record the telephone conversations of O’Brien. In fact, O’Brien never used this office telephone.

(5) E. Howard Hunt was in charge of photographing documents found in the DNC offices. The two rolls of film were supposed to be developed by a friend of James McCord. This did not happen and eventually Hunt took the film to Miami for Bernard Barker to deal with. Barker had them developed by Rich’s Camera Shop. Once again the conspirators were providing evidence of being involved in the Watergate break-in.

(6) The developed prints showed gloved hands holding them down and a shag rug in the background. There was no shag rug in the DNC offices. Therefore it seems the Democratic Party documents must have been taken away from the office to be photographed. McCord later claimed that he cannot remember details of the photographing of the documents. Liddy and Jeb Magruder saw them before being put in John Mitchell’s desk (they were shredded during the cover-up operation).

(7) After the break-in Alfred Baldwin and James McCord moved to room 723 of the Howard Johnson Motor Inn in order to get a better view of the DNC offices. It became Baldwin’s job to eavesdrop the phone calls. Over the next 20 days Baldwin listened to over 200 phone calls. These were not recorded. Baldwin made notes and typed up summaries. Nor did Baldwin listen to all phone calls coming in. For example, he took his meals outside his room. Any phone calls taking place at this time would have been missed.

(8) It soon became clear that the bug on one of the phones installed by McCord was not working. As a result of the defective bug, McCord decided that they would have to break-in to the Watergate office. He also heard that a representative of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War had a desk at the DNC. McCord argued that it was worth going in to see what they could discover about the anti-war activists. Liddy later claimed that the real reason for the second break-in was “to find out what O’Brien had of a derogatory nature about us, not for us to get something on him.”

(9) Liddy drove his distinctive Buick-powered green Jeep into Washington on the night of the second Watergate break-in. He was stopped by a policeman after jumping a yellow light. He was let off with a warning. He parked his car right outside the Watergate building.

(10) The burglars then met up in room 214 before the break-in. Liddy gave each man between $200 and $800 in $100 bills with serial numbers close in sequence. McCord gave out six walkie-talkies. Two of these did not work (dead batteries).

(11) McCord taped the 6th, 8th and 9th floor stairwell doors and the garage level door. Later it was reported that the tape on the garage–level lock was gone. Hunt argued that a guard must have done this and suggested the operation should be aborted. Liddy and McCord argued that the operation must continue. McCord then went back an re-taped the garage-level door. Later the police pointed out that there was no need to tape the door as it opened from that side without a key. The tape served only as a sign to the police that there had been a break-in.

(12) McCord later claimed that after the break-in he removed the tape on all the doors. This was not true and soon after midnight the security guard, Frank Wills, discovered that several doors had been taped to stay unlocked. He told his superior about this but it was not until 1.47 a.m. that he notified the police.

(13) The burglars heard footsteps coming up the stairwell. Bernard Barker turned off the walkie-talkie (it was making a slight noise). Alfred Baldwin was watching events from his hotel room. When he saw the police walking up the stairwell steps he radioed a warning. However, as the walkie-talkie was turned off, the burglars remained unaware of the arrival of the police.

(14) When arrested Bernard Barker had his hotel key in his pocket (314). This enabled the police to find traceable material in Barker’s hotel room.

(15) When Hunt and Liddy realised that the burglars had been arrested, they attempted to remove traceable material from their hotel room (214). However, they left a briefcase containing $4,600. The money was in hundred dollar bills in sequential serial numbers that linked to the money found on the Watergate burglars.

(16) When Hunt arrived at Baldwin’s hotel room he made a phone call to Douglas Caddy, a lawyer who had worked with him at Mullen Company (a CIA front organization). Baldwin heard him discussing money, bail and bonds.

(17) Hunt told Baldwin to load McCord’s van with the listening post equipment and the Gemstone file and drive it to McCord’s house in Rockville. Surprisingly, the FBI did not order a search of McCord’s home and so they did not discover the contents of the van.

(18) It was vitally important to get McCord’s release from prison before it was discovered his links with the CIA. However, Hunt or Liddy made no attempt to contact people like Mitchell who could have organized this via Robert Mardian or Richard Kleindienst. Hunt later blamed Liddy for this as he assumed he would have phoned the White House or the Justice Department who would in turn have contacted the D.C. police chief in order to get the men released.

(19) Hunt went to his White House office where he placed a collection of incriminating materials (McCord’s electronic gear, address books, notebooks, etc.) in his safe. The safe also contained a revolver and documents on Daniel Ellsberg, Edward Kennedy and State Department memos. Hunt once again phoned Caddy from his office.

(20) Liddy eventually contacts Magruder via the White House switchboard. This was later used to link Liddy and Magruder to the break-in.

(21) Later that day Jeb Magruder told Hugh Sloan, the FCRP treasurer, that: "Our boys got caught last night. It was my mistake and I used someone from here, something I told them I’d never do."

(22) Police took an address book from Bernard Barker. It contained the notation "WH HH" and Howard Hunt’s telephone number.

(23) Police took an address book from Eugenio Martinez. It contained the notation "H. Hunt WH" and Howard Hunt’s telephone number. He also had cheque for $6.36 signed by E. Howard Hunt.

(24) Alfred Baldwin told his story to a lawyer called John Cassidento, a strong supporter of the Democratic Party. He did not tell the authorities but did pass this information onto Larry O’Brien. The Democrats now knew that people like E. Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy were involved in the Watergate break-in.

Several individuals seem to have made a lot of mistakes. The biggest offenders were Hunt (8), McCord (7), Liddy (6), Barker (6) and Baldwin (3). McCord’s mistakes were the most serious. He was also the one who first confessed to what had taken place at Watergate.

(11) Alfred C. Baldwin, International Education Forum (21st December, 2005)

I was assigned to guard Martha Mitchell and I have no idea why she referred to me as "the most gauchest character". I was later told that it was due to the fact that I had attended a cocktail party and had taken my shoes and socks off and had placed my bare feet on a cocktail table in front one of the President's cabinet members, I believe the Secretary of Transportation Volpe. This was totally false and I was willing to take a lie detector test to prove that I had never ever been in the presence of any cabinet member. The FBI was satisfied with my statement on this subject, and if there was any truth to Martha's clam of gaucheness I am sure that her husband would not have allowed my continued employment at the Committee To Re-Elect The President where he became the chairman after leave the cabinet post of Attorney-General.

My story was never told to John Cassidento initially. The lawyer who hear it first hand was my friend and classmate at law school, Robert Mirto, who latter appeared at the congressional hearings with me. John was an Assistant Federal Prosecutor in New Haven, not Hartford, who subsequently joined Mr. Mirto's law firm actually in West Haven, CT. Mr Mirto is still practicing law in West Haven. Mr Cassidento is deceased.

I did not cooperate to escape prison. The question of indictment must first be meet, then a trail if indicted, then prison if convicted. Since my position the and today is that we were operating under the orders, or with the authority of the Attorney-General, what took place was legal. I was cooperating to avoid the grand-jury not prison.

One last point, I never meet nor was I ever interviewed by Mark Felt.

(12) Alfred C. Baldwin was interviewed by John Simkin on the International Education Forum (24th December, 2005)

John Simkin: What work were you doing between 1966 and 1972?

Alfred Baldwin: Between 1966 and 1972 I worked as the Director of Security for a multi-state trucking firm. I left this position to work for a retired Naval Admiral who was creating a college degree program for law enforcement personnel who desired a college degree in the police administration and law enforcement field. I was hired as his assistant with the task of hiring adjunct professors as well as teaching law related subjects. The college was the University of New Haven located in New Haven. Yes, there are other colleges/universities other than Yale located in New Haven.

John Simkin: Did you know James W. McCord before he recruited you in 1972?

Alfred Baldwin: Prior to 1972 I did not know James McCord, but I was aware of the fact that he was a former Special Agent with the FBI.

John Simkin: Were you an active supporter of Richard Nixon's before 1972?

Alfred Baldwin: No.

John Simkin: Did you know any of the following before 1972: Anthony Ulasewicz, Douglas Caddy, Carmine Bellino, Timothy J. Gratz, Jack Caulfield, E. Howard Hunt, Lou Russell, Donald Segretti and G. Gordon Liddy?

Alfred Baldwin: No.

John Simkin: Did you do any work for Operation Gemstone or Operation Sandwedge before the Watergate break-in?

Alfred Baldwin: You will have to define operation Gemstone. The files I complied were referred to as Gemstone. No with respect to Operation Sandwedge.

John Simkin: Are you aware of the real reason why the Watergate offices were burgled?

Alfred Baldwin: I have my own personal opinion based on my conversations with McCord at that time, and I should add this opinion hasn't changed in any way even with all the information and data that has come forth since 1972.

John Simkin: It became your job to eavesdrop the phone calls. I believe that over a 20 day period you listened to over 200 phone calls. Could you explain the sort of information that McCord was looking for.

Alfred Baldwin: Will leave this for a future reply because it might require a lengthy explanation.

John Simkin: Gordon Liddy later claimed that the real reason for the second break-in was “to find out what O’Brien had of a derogatory nature about us, not for us to get something on him.” Is that your understanding of the situation as well?

Alfred Baldwin: Gordon can state whatever he wants. I worked for McCord who may not have Liddy's viewpoint.

John Simkin: On 17th June, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord returned to O'Brien's office. It was your job to observe the operation from his hotel room. I believe that when you saw the police walking up the stairwell steps you radioed a warning. However, Barker had turned off his walkie-talkie and you were unable to make contact with the burglars. Is that correct?

Alfred Baldwin: I really cannot make a judgement call on what Mr. Baker did or didn't do because my communications where with McCord. Now if McCord gave his unit to Baker your statement might be relevant.

John Simkin: Is it true that when E.Howard Hunt arrived at your hotel room he made a phone call to Douglas Caddy?

Alfred Baldwin: True Hunt on arriving at my room did make a call to someone who I realized was a lawyer due to the nature of the conversation coming from Hunt. No name was ever used so I can not name that person.

(13) Katharine Q. Seelye, New York Times (10th May, 2022)

Alfred C. Baldwin III had a ringside seat to the hapless Watergate break-in on June 17, 1972. He was the lookout, watching from a perch across the street with a mission to warn his burglary compadres inside the Watergate complex if law enforcement was approaching.

When he finally did see the police swoop in, he was too late to warn the burglars. He fled from his lookout post but was later picked up by the F.B.I.

In the motley cast of oddballs, miscreants, would-be spies and dirty tricksters involved in the ensuing two-year Watergate drama - which culminated with President Richard M. Nixon's resignation in 1974 - Mr. Baldwin was a minor character. But he played a crucial early role by becoming a witness for the government and by being among the first to connect the dots publicly between the burglars and Nixon's re-election efforts.

His account of his involvement, provided to The Los Angeles Times a few months after the break-in, was "perhaps the most important Watergate story so far," the journalist and author David Halberstam wrote in 1979 in "The Powers That Be," a book about the media.

"It was so tangible," he added, "it had an eyewitness, and it brought Watergate to the very door of the White House."

Mr. Baldwin died more than two years ago, on Jan. 15, 2020, but the news only recently came to light. It was first reported by Shane O'Sullivan, an Irish author and filmmaker, who was updating his book, "The Watergate Burglars" (originally published in 2018 as "Dirty Tricks"). The news became public on May 3 when Mr. O'Sullivan's book was issued in paperback. He said that Mr. Baldwin, who was 83, died at a care facility in New Paltz, N.Y.

The New York Times confirmed the death with Mr. Baldwin's lawyer and longtime friend, Robert C. Mirto. The cause was cancer.

Mr. Baldwin, a former F.B.I. agent, had been recruited in May 1972 to work for the Committee to Re-Elect the President, known as CREEP, by James W. McCord Jr., a former security expert at the C.I.A. who masterminded the Watergate burglary. (Coincidentally, Mr. McCord's death in 2017 was also overlooked for two years and was also first reported by Mr. O'Sullivan.)

Mr. Baldwin first provided a vivid account of his role in a 1972 interview with Jack Nelson, a reporter with The Los Angeles Times. The account was among the first in which the public learned details of the break-in, including that the one in June, in which the burglars were caught, was their second visit to the offices of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate.

During the first break-in, in late May, the burglars installed two listening devices, Mr. Baldwin said in his interview. He was stationed across the street at the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge, from which he eavesdropped on the phone taps. He had logged about 200 calls by the time Mr. McCord realized that the bugging devices weren't working properly and decided to stage a second incursion on June 17 to adjust them.

It was not clear at what point Mr. Baldwin saw that the police had arrived on the scene. A 2012 account in Washingtonian magazine said that at the time he was "glued to the TV watching a horror movie, ‘Attack of the Puppet People,' on Channel 20 � oblivious to the situation developing across the street."

But that account was wrong, Mr. Baldwin said. He said he had turned on the television to cover up the sound of his walkie-talkie, which he was using to communicate with the burglars.

Washingtonian reported that by the time he "noticed that things had gone awry across the street, it was too late" � undercover District of Columbia police had already arrived, thanks to a call from Frank Wills, the Watergate security guard, who noticed tape on the door to the D.N.C. headquarters, which prevented it from being locked.

Mr. Baldwin said he had seen the officers' cars massing outside the Watergate and got on his walkie-talkie to alert the burglars to "men with guns and flashlights looking behind desks and out on the balcony."

In short order, uniformed police swarmed the scene, and the jig was up. E. Howard Hunt, one of the conspirators who had slipped out of the Watergate, rushed over to Mr. Baldwin's motel room, told him to pack up the surveillance equipment, take it to Mr. McCord's house and then disappear.

"Does that mean I'm out of a job?" Mr. Baldwin said he asked Mr. Hunt. But by then Mr. Hunt was out the door.

Federal investigators quickly tracked down Mr. Baldwin. By the end of the month he was cooperating with the government, the only participant not indicted. He testified before the Senate Watergate Committee in May 1973, fleshing out the narrative he had told Mr. Nelson.

Alfred Carleton Baldwin III was born on June 23, 1936, in New Haven, Conn. His father was a lawyer and a state unemployment compensation commissioner. Alfred's great-uncle, Raymond E. Baldwin, who died in 1986, had served as Connecticut's governor, a United States Senator representing the state and its chief justice.

Alfred earned his degree in business administration from Fairfield University in Connecticut in 1957 and joined the Marines. He earned his law degree at the University of Connecticut law school, graduating in 1963, and joined the F.B.I. later that year. He was assigned to various cities in the South, then resigned three years later when he married Georgeann Porto and moved back to Connecticut. The marriage soon ended in divorce.

Mr. Baldwin worked as director of security for a trucking company and as an instructor in a college program for law-enforcement officers until he was recruited by Mr. McCord to join CREEP.

Mr. Baldwin's first assignment was to provide security for Martha Mitchell, whose husband, John N. Mitchell, had stepped down as attorney general to work on Mr. Nixon's re-election campaign. They were not a good match.

"Al Baldwin is probably the most gauche character I have ever met in my whole life," Ms. Mitchell later said in a Watergate deposition. For one thing, she said, he had taken off his shoes and socks in her hotel suite.

Mr. Mirto, Mr. Baldwin's lawyer, said in an interview that Mr. Baldwin was a "fun-loving guy." He was so drawn to women, Mr. Mirto said, that if he spotted an attractive one driving on the turnpike, he would drive in front of her and pay her toll, then ask her out for a drink. He said this worked about 10 times.

When he spoke to Mr. Nelson at The Los Angeles Times, Mr. Baldwin had one request � that he be described as "a husky ex-Marine" in an attempt to impress a woman he was seeing. Mr. Nelson complied.

After Watergate, Mr. Baldwin struggled to find work. He finally landed a job as a substitute teacher in New Haven. He received a master's degree in education from Southern Connecticut State College (now University). And though he had received his law degree two decades earlier, he took the bar exam for the first time in 1987 and passed.

He later became a state prosecutor in Hartford, his last job before retiring.

: