Evgenia Shelepina

Evgenia Shelepina, the daughter of Peter Shelepina, was born in Gatchina on 10 April 1894. The eldest child of six, with two sisters and three brothers: Iroida, Serafima, Viktor, Roman and Gleb. Her father was born a serf but following emancipation became the curator of the Tzar's Imperial Hospital and Charity Institute in the town. Evgenia was educated locally.

In 1912 she became a student at the Stenography College in Petrograd. In early 1915 she found work for the Ministry of Trade and Industry as a typist. Shelepina became disillusioned with the rule of Tsar Nicholas II and became a supporter of the Bolsheviks. She was in the city when the Russian Revolution took place: "On that first day I remember seeing the sailors and workmen with their flags crossing over the bridge. Everybody crowded to the windows of the Ministry to look out. But they were not at all pleased. I was very pleased. They crowded to the window and then drew back again when they heard the shooting in the town, and were telling each other that the crowd would come in and shoot them next. They were sure that the people would come in and kill everybody in the Ministry, but they dared not leave because of the shooting.... I was pleased to see the workmen and sailors and excited and happy, because I wanted them to win."

Shelepina was taken ill and returned to Gatchina. Most of Shelepina's colleagues opposed the revolution: "I heard that everybody in my Ministry had met and passed a resolution not to work for the Bolsheviks, but to go on strike. I asked whether anybody had voted against the resolution, and was told that only two had refused to vote, but all the rest were for striking. I wished I had been in Petrograd so that there should have been at least one vote against striking.... Nearly everybody had worked there during the old regime, and under Kerensky, and they all believed that the Bolsheviks would only stay in power a few days, and that if they went in with the Bolsheviks they would presently be left between two stools."

When she recovered from her illness she went to Petrograd and offered her services to the new government: "I said, I could do anything they wanted, that I could typewrite, and take shorthand notes, and knew a little book-keeping, that I was willing to do anything they thought useful. They asked what party I belonged to, and I showed them my card of membership of the Bolshevik party. Then they gave me some typewriting to do in the Ministry of Labour.... The person in charge of the department where I worked was a young woman, not very well educated. She knew I had worked in a Ministry before, and perhaps for that reason made a particular show of friendliness for me, though being laughably careful not to let me forget that she was in charge and that I was under her supervision, though she could make no pretence of understanding the work."

A few weeks later she was told that Leon Trotsky was looking for a secretary. The official said, "We want people for the Foreign Office. Do you know any foreign languages?" Evgenia Shelepina replied: "I said I could tell one from another, but I could not talk any of them." He said, "That is unfortunate, but it cannot be helped, and we can get no one at all. Trotsky wants some practical sensible person for a secretary, and we can trust you, and you belong to the party." Shelepina went off to the Smolny Institute: "I found Trotsky in that same room where I used to see him, at the end of the corridor on the third floor... Trotsky sat on one side of the table and I sat on the other. I did not hide from him that I was quite unfit for the work, but that I wanted to do anything I could."

Evgenia Shelepina admitted: "At first I did not know how to talk to Trotsky. I thought of him as of someone so great, and so high, all of whose time was given to the work. It was almost a shock to me to find that he had a daughter. I did not think of him having any human relations at all. I did not know how to address him. Once only I called him Comrade Trotsky. It came out very funnily, and he immediately called me Comrade Shelepina, and we both laughed. After that I always called him Lev Davidovitch, and he called me Evgenia Petrovna."

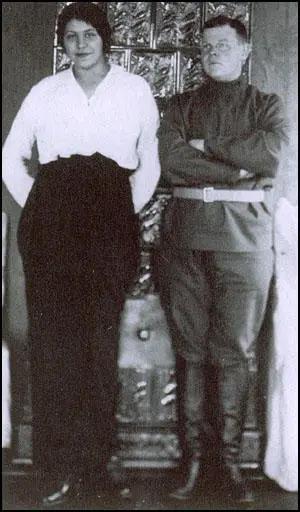

George Alexander Hill, a British diplomat in Petrograd, discovered that Shelepina became an important part in the Trotsky team. "She must have been two or three inches above six feet in her stockings... At first glance, one was apt to dismiss her as a very fine-looking specimen of Russian peasant womanhood, but closer acquaintance revealed in her depths of unguessed qualities.... She was methodical and intellectual, a hard worker with an enormous sense of humour. She saw things quickly and could analyse political situations with the speed and precision with which an experienced bridge player analyses a hand of cards... I do not believe she ever turned away from Trotsky anyone who was of the slightest consequence, and yet it was no easy matter to get past that maiden unless one had that something."

Evgenia Shelepina met Arthur Ransome when he interviewed Leon Trotsky on 28th December 1917. Shelepina was Trotsky's secretary. Ransome, who was unhappily married to Ivy Walker Ransome, fell in love with Shelepina. Ransome's biographer, Roland Chambers, has pointed out: "Over forty years later, Ransome remembered the decisive moment at which he realized he was in love: a mixture of terror and relief over which he had no power whatsoever. But as he snatched his future wife from beneath the wheels of history - the war, the Revolution, the fatal passage of circumstance which Lenin had declared indifferent to the fate of any single individual - the possibility of separating his private from his professional affairs remained as remote as ever."

Evgenia Shelepina was a major source of secret information. Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013) commented that: "Their relationship was to transform the information he received from the regime: it was Shelepina who typed up Trotsky's correspondence and planned all his meetings. Suddenly, Ransome found himself with access to highly secretive documents and telegraphic transmissions."

Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009) argued: "Ransome's articles reflected the party line so accurately that there was little to choose between them but style, while as his relationship with Evgenia deepened, so any change of heart or sudden epiphany became that much more improbable. In his autobiography, she is pictured either as a distant functionary, handing out official releases, or as guardian of his personal happiness; never both at the same time. They had grown together gradually, as ordinary people do, strolling in the evenings, taking supper at the rooms she shared with her sister at the commissariat's headquarters in the centre of town."

Ransome developed a very intense relationship with Evgenia Shelepina and told her that as soon as he could arrange a divorce from Ivy Constance Ransome he would marry her. In his autobiography he recalled, that she had slipped when boarding a tram, and clutching the rail, was dragged full length along the track, so that if her grip had failed she would have been cut in two. "Those few horrible seconds during which she lay almost under the advancing wheel possibly determined both of our lives. But it was not until afterwards that we admitted anything of the kind to one another."

Ransome's position became more difficult when it became clear that Winston Churchill, Britain's Minister of War, wanted to support the White Army in the Russian Civil War. On 27th August, 1919, British Airco DH.9 bombers dropped chemical weapons on the Russian village of Emtsa. According to one source: "Bolsheviks soldiers fled as the green gas spread. Those who could not escape, vomited blood before losing consciousness."

Ransome contacted his spymaster, Robert Bruce Lockhart, to help him and Evgenia, to escape from Russia to Estonia by providing the necessary papers. Lockhart agreed and sent a telegram to the Foreign Office in London asking for help. "A very useful lady, who has worked here in an extremely confidential position in a government office desires to give up her present position... She has been of the greatest service to me and is anxious to establish herself in Stockholm where she would be at the centre of information regarding underground agitation in Russia... In order to enable her to leave secretly, I wish to have authority to put her to Mr Ransome's passport as his wife and facilitate her departure via Murmansk." Arthur Balfour, the Foreign Secretary, arranged for the papers to be sent to Russia.

Evgenia Shelepina returned to England with Arthur Ransome and married her on 8th May 1924, having finally secured a divorce from Ivy Walker Ransome. In 1925, C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, sent Ransome to report on China. He also wrote the newspaper's Country Diary column on fishing.

In 1929 Ransom began writing novels for children. Although not immediately successful, his books eventually became best-sellers. The twelve books include Swallows and Amazons (1930), Swallowdale (1931), Peter Duck (1932), Winter Holiday (1933), Coot Club (1934) and Pigeon Post (1936). According to Jon Henley the "children's books had sold more than a million copies by the time the last was published, and have sold many millions more since."

Evgenia Shelepina Ransome died on 13th March 1975.

Primary Sources

(1) Evgenia Shelepina, unpublished memoirs (c. 1920)

The day before the revolution, we had taken a room together on the Vassilievsky Ostrove and we sat there a little and drank tea, and thought what fools we had been not to have done so earlier, and so escape the difficulty of travelling in and out of Petrograd. But we had not moved in, and on the morning of the revolution we came in together from Gatchina as usual.

On that first day I remember seeing the sailors and workmen with their flags crossing over the bridge. Everybody crowded to the windows of the Ministry to look out. But they were not at all pleased. I was very pleased. They crowded to the window and then drew back again when they heard the shooting in the town, and were telling each other that the crowd would come in and shoot them next. They were sure that the people would come in and kill everybody in the Ministry, but they dared not leave because of the shooting.

I tried to telephone Eroida, because we had agreed to meet at the station at six o clock to go home by train together. The telephone was not working. So I went to the station. I was never under fire. I have always had bad luck. I have never once been under fire all throughout the Revolution. Of course I heard firing all the time. Sometimes it was in the next street. Sometimes it was far away, but I got the whole way to the station without being in any danger at all. I was pleased to see the workmen and sailors and excited and happy, because I wanted them to win.

I waited at the station for four hours not knowing what had become of Eroida. Then, thinking that perhaps she might have gone home earlier, I got into a train that was just leaving and went home. I found mother in Gatchina in great anxiety. She accused me of deserting Eroida, and asked me how I could have come home without her. There were tears and cries and general disturbance. Mother had heard all sorts of rumours and no one knew what was happening. She was angry with me because I could not tell her. I did not know myself although I had come from Petrograd. I put on my coat and was for going back to town, but mother would not have that either.

Eroida got back early the next morning. She had gone to a friend's rooms when the fighting began, and the fighting had come to that very street. People were firing up and down the street so that she could not get out. It was just like Eroida to have all the experience when I really wanted to have it. At last when things were quieter, she and another girl who lived in Gatchina also, went out. Almost as soon as they were in the street they had to lie flat on the ground because someone with a machine gun was firing at anything that moved in the street. They had to lie down six times before they got to the station.

For the next three days I was ill, and then for two weeks the trains were not running between Gatchina and Petrograd. Kerensky was in Gatchina and every day we expected troops from the front, but I was hoping they would not come. We used to send messengers to the station every day to know if a train was going. Then I heard that everybody in my Ministry had met and passed a resolution not to work for the Bolsheviks, but to go on strike. I asked whether anybody had voted against the resolution, and was told that only two had refused to vote, but all the rest were for striking. I wished I had been in Petrograd so that there should have been at least one vote against striking. Ours was a very black hundredish ministry.

Nearly everybody had worked there during the old regime, and under Kerensky, and they all believed that the Bolsheviks would only stay in power a few days, and that if they went in with the Bolsheviks they would presently be left between two stools. I used to go to the station myself to ask about trains. Perhaps you will understand. Quite there too. I could not find one. There was a crowd of students and girl students and others, and so I waited with them.

I was asked "What recommendations have you?"

I said, "I have no recommendations at all, but I worked in the Ministry of Trade and Industry for so long."

I was asked, "What can you do?"

I said, I could do anything they wanted, that I could typewrite, and take shorthand notes, and knew a little book-keeping, that I was willing to do anything they thought useful.

They asked what party I belonged to, and I showed them my card of membership of the Bolshevik party. Then they gave me some typewriting to do in the Ministry of Labour. I set to work at once, and so on the evening of the day I left Gatchina, I was already at work. The Marble Palace, which is the Ministry of Labour, had magnificent rooms, and its' beauty and the feeling of solidarity in it had a quieting effect upon me. I felt better already, as soon as I was at work there.

The person in charge of the department where I worked was a young woman, not very well educated. She knew I had worked in a Ministry before, and perhaps for that reason made a particular show of friendliness for me, though being laughably careful not to let me forget that she was in charge and that I was under her supervision, though she could make no pretence of understanding the work. Every day fresh people came in to work, and as all applications passed through the Ministry of Labour, I used to go every day to look at the lists to see if any of the people from the old Ministry of Trade and Industry had come in, because I was always hoping that I should get back to my old place and be part of the old machine that I knew, and see it working as before. But not one of them came in.

The man who was at the head of what they called the Committee of Mobilisation which dealt with the organisation of work and finding workers for the Ministries used to laugh at me for being so anxious to get back to my old post. We used to talk together, and I told him how I looked at things. One day he came to me and said, "We want people for the Foreign Office. Do you know any foreign languages?" I said I could tell one from another, but I could not talk any of them. He said, "That is unfortunate, but it cannot be helped, and we can get no one at all. Trotsky wants some practical sensible person for a secretary, and we can trust you, and you belong to the party." I told him I wanted to get back to my old place in my old Ministry, and he promised that this work should be only temporary, and that I ought to do it. I was anxious to do something more than write on a typewriter, so I agreed, and went off to Smolny. I found Trotsky in that same room where I used to see him, at the end of the corridor on the third floor. It was differently furnished then. There was just one table in the corner by the two windows. In the little room partitioned off was some dreadful furniture, particularly a green divan with a terrible pillow on it. You see it had been the room of the resident mistress on that floor of the Institute when it was still an Institute for girls. Trotsky sat on one side of the table and I sat on the other. I did not hide from him that I was quite unfit for the work, but that I wanted to do anything I could.

It was settled that I should begin at once. The first work I did was to make that dreadful room into a place fit to work in. Trotsky gave me a paper to take to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to get a good typewriter, instead of the broken one that was in the room for show, and telephoned for his motor car to take me there and bring me back with the machine and some furniture. He gave me two soldiers to help in getting the furniture. I remember we had to wait a very long time before the motor car was ready.

We went to the Foreign Office, and there found Zalkind (who was for a time assistant Commissary for Foreign Affairs, and afterwards was sent as Russian Minister to Berne) in his room, which was just as you saw it, if not worse. Zalkind was half dressed, his hair wanted combing, the room was like a lumber room. The sofa where he slept was still like the nest of a wild beast. The big table with its red felt top was dusty and piled with papers, and inkpots which had been used for ash trays, and glasses with the dregs of coffee in them, and old bits of bread from the day before.

There were half a dozen people in the room, and Zalkind took the note I had brought him from Trotsky, read it aloud, and said, pointing at me, "We have destroyed secret diplomacy and come to that." I did not like his manner. He told me to find the sailor Markin who knew where everything was. Then I met a very neatly dressed sailor.

Markin was not at all so anxious to look proletarian in the first days as he was later. Then he was dressed very carefully in a neat uniform, and his beard properly trimmed. Markin had very little education, but had a most amusing way of saying 'surprising', 'extraordinary' and 'astonishing', not like most people say those words, but as if they were newly forced out of him by his real feeling of the sensations that they suggest. In those days he was very elegant. He took me to the room where I afterwards went to live, where we found the machine we wanted, and a table and some good chairs, all of which I took back with me to the Smolny, so that next day room 67 was already a place where it was possible to work.

The rear of room 67 was screened off as a private quarter for Trotsky. In this room one day, there was a young girl with hair cut short like a boy. She was sitting at the table doing nothing, and afterwards went with me to the refectory downstairs. This was a big barrack of a room with sawdust and spilt soup all over the floor, and bare tables. You bought tickets at a side table, and then took your place in a long queue, and when your turn came, received a bowl of soup, very hot, and, as you passed by grabbed a wooden spoon out of a basket. The soup was very hot, the plates very deep, and the spoons so large that sometimes it was impossible to get the soup into them at all. Then there was dark coloured tough macaroni, which I did not know how to eat. I could not pick it up on the big wooden spoon, and I did not see where forks were to be had. Most of the soldiers sitting about were eating with their fingers. A few had forks, but I thought they had brought them with them, and decided to bring a fork myself next time. I asked the short haired girl what work she did, and she answered that she did no work at all. I said I thought that was bad, but she explained that she was Trotsky's daughter, and was studying. She was about sixteen, very like Lev Davidovitch, with fine eyes, and a rather malicious expression. Trotsky has been married twice, and this was one of the children of his first marriage.

Downstairs in the refectory there was a woman serving out food. I think she had served there in the time when Smolny was still an institute for girls, and she was always thinking of old times, and comparing the comrades with the noble young ladies whose places they had taken.At first I did not know how to talk to Trotsky. I thought of him as of someone so great, and so high, all of whose time was given to the work. It was almost a shock to me to find that he had a daughter. I did not think of him having any human relations at all. I did not know how to address him. Once only I called him Comrade Trotsky. It came out very funnily, and he immediately called me Comrade Shelepina, and we both laughed. After that I always called him Lev Davidovitch, and he called me Evgenia Petrovna.

I with my long training in a Ministry under the old regime, was offended somehow, for the dignity of the Ministry, when I found Trotsky himself taking thought about the arrangement of his room. This table was to be in that place, and this chair here. It seemed to me that there ought to be a whole corps of people to think of all these things, and that Trotsky should have no attention to spare for such matters. I always remember the affair of the phonograph. He asked me if I could write shorthand. I was terribly ashamed because I could not. He said, "In the Ministry of Foreign Affairs there is a phonograph. We will use that." So I went off to the Ministry and found Markin, and after a long hunt we found the phonograph and brought it back.

Trotsky never used it, but we fixed it on the table by his desk. There it stood always, and had a most imposing appearance. Perhaps that was all he wanted it for. It was only just before we left Petrograd that we found out how to work it. Everything was almost packed, and we were in a cheerful mood, expecting every day that the Germans would come in and hang us all, and make a good end of it. Soldier Jukov took the phonograph, and got it to work. He shouted English songs into it. You know how he talks English. Then I shouted into it. Then we made it shout back. On that last day three young people from one of the guerrilla detachments came in to look for Trotsky. They found us playing with the phonograph, and they shouted into it too, all kinds of rubbish, songs, and German swear words. If the Germans find it and turn it on thinking to discover state secrets, they will be surprised by a funny medley of cheerful noises.

At first very few visitors came to room 67. They were mostly foreigners asking for passports to go abroad. Russians too. I used to let almost all of them see Trotsky, particularly the foreigners. I was a little more careful with the Russians. But at first I had no idea what was important and what was not. For example, I tore up and threw away all the replies of the Foreign Embassies to Trotsky's note inviting them to join in discussions of general peace.

The first real bit of Foreign Relations we had was with the King of Sweden. There came along a certain Svanstrom or Swenstrom, from the Swedish Red Cross, with a letter suggesting the making of a neutral zone so that the exchange of invalid prisoners could go on directly through the front instead of by the roundabout way through Torneo. Svanstrom spoke to me in French, and I was ashamed at having to reply in French, and was still more ashamed when it turned out afterwards that he could talk Russian. I was ashamed, not for myself, you understand, but for the dignity of the Commissariate of Foreign Affairs. I did not think that they ought to know that Trotsky had not been able to get a secretary who could talk French. Well, worse was to come.

Svanstrom was to leave for Sweden in two days time, and Trotsky promised an answer to take back to the king of Sweden. Well, the first day passed, and Trotsky did nothing. I could not think he had forgotten it, and I did not like to remind him. Then Svanstrom came for it, and I told him it was not quite ready but would be ready in time, and that it would be sent to him. Still Trotsky did nothing. The next day was Sunday. Trotsky wrote the reply on a scrap of paper, and gave it to me to have it properly typewritten so that it could be given to Svanstrom for the king. Our typewriter, which wrote with English or French characters was a very bad one, so I sent it to the Foreign Office.

It was Sunday and no one was there. At last very late it came back. It was written on beautiful paper, but dirty, you should have seen it. It was full of mistakes which had been rubbed out with indiarubber, and the indiarubber still showed. It was not that it was to be handed to the King that gave cause for concern. It was that any foreigner should think we were such a set of uneducated barbarians as to be unable to send out a neater looking document. I did not know what to do. So I tried to make a cleaner copy on the old English machine in room 67. Its ribbon was full of copying ink, so that it smudged, and the machine itself was filthy. It had not been used for I don't know how long. My first copy was worse than the original. The second was not much better, and I spent hours over them, because I was accustomed to write on a Russian machine, and all the letters were in different places, and I had to look at each letter, because I did not know how the French words were spelt. And I did not know how to put the accents on. Then Trotsky came in, and I told him the whole story and showed him the three copies to choose from. He chose the first, and laughed and told me to put it in an envelope. Nor was even that the end. We were to give Svanstrom a pass and also a Swedish officer who was to go with him. And we sent neither the passes nor the letter. They came for them themselves early in the morning. I nearly died of shame when I handed them the envelope, and then, to make things worse, the Swedish officer kissed my hand. It was so unexpected, for one thing, and there were a lot of people about, and I thought it would seem to them altogether like bourgeois times and the old regime. Altogether it was a most unfortunate incident. And with that began Bolshevik dealings with foreign powers.

(2) Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013)

Ransome was soon so close to the leading revolutionaries that Western diplomats began to wonder if he had "unusual channels of information." This he did. Unbeknown to anyone in London, he had fallen in love with Trotsky's personal secretary, Evgenia Shelepina, and was seeing her on a daily basis.

Their relationship was to transform the information he received from the regime: it was Shelepina who typed up Trotsky's correspondence and planned all his meetings. Suddenly, Ransome found himself with access to highly secretive documents and telegraphic transmissions.

He had first set eyes on Evgenia when he interviewed Trotsky on 28 December 1917, but he did not speak to her until later that evening, when he visited the Commissariat for Foreign Affairs. He poked his head into a room and, amid a group of unfamiliar faces, immediately recognised her.

"This was Evgenia," he would write, "the tall, jolly girl whom later on I was to marry and to whom I owe the happiest days of my life."

Ransome had been looking for the official censor to stamp his despatch: Evgenia offered to help him find the right person. She also said she would try to find them both some food in the censor's office. "Come along," she said, "perhaps he has some potatoes. Potatoes are the only thing we want. Come along."

They eventually found both the censor and his potatoes: the latter were in the process of burning on an overheated primus stove. Evgenia rescued them from the pot and shared them out...

The Americans in Petrograd called her "The Big Girl" because, explained one, "she was a big girl". She played an important role in the months that followed the revolution for she controlled the visitors who wished to get Trotsky's ear. She was far more than a secretary; she could provide (or deny) access to all of the Bolshevik leaders...

Ransome took the new Bolshevik leadership very seriously and his reports on their activities - often sympathetic - caused him increasing difficulties with officials in London. His relationship with Evgenia did not help matters. In the British Embassy in Petrograd, there were whispered rumours that far from serving the British government, he was actually working as a double agent.

Ransome did little to discourage these rumours for they only served to boost his credentials amongst the leading Bolsheviks. Besides, he shared some of the views of the revolutionary leaders and genuinely hoped that Lenin and Trotsky would drag Russia into a brighter future.....

An ill-timed telegram from Foreign Commissar Georgy Chicherin only increased the fears of the ambassadors. The commissar warned them that their lives would be in grave danger unless they immediately returned to Moscow. His words had quite the opposite effect. On 25 July, all of the foreign diplomats in Vologda boarded a train to Archangel and left Bolshevik Russia forever.

In the aftermath of their departure, Ransome once again found himself accused of having pro-Bolshevik sympathies. Major-General Knox was the most outspoken about Ransome's intimacy with the Bolshevik leaders: on one occasion, he went so far as to say that he should be "shot like a dog."

But Ransome had personal reasons for fearing a rupture of relations with Moscow. It was certain to lead to his expulsion from the country, along with the other remaining Westerners, and this would have serious ramifications on his relationship Evgenia. The two of them could not marry, for Ransome already had a wife, and Evgenia (as his mistress) was unlikely to be granted an entry visa for Britain. Yet she faced a potentially dangerous situation if she remained in Moscow. Ransome feared that the Allied powers would march on Moscow and purge Russia of its Bolshevik masters. If so, Evgenia would be caught in the maelstrom.