On this day on 31st December

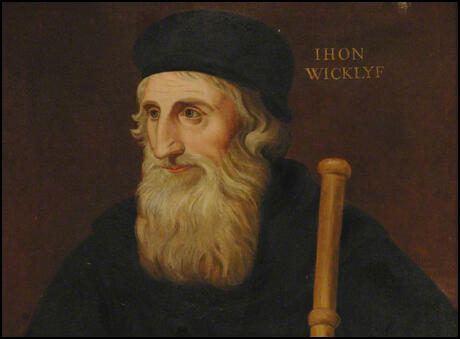

On this day in 1384 John Wycliffe died. Wycliffe was born in Ipreswell in Yorkshire in about 1325. Information about his early life is scarce. Wycliffe came from a wealthy country and in about 1350 went to Balliol College.

According to his biographer, Anne Hudson: "There is good reason to think that Wycliffe was a member of the Richmondshire family from the North Riding village of Wycliffe; he can probably be identified with either Johannes filius Willelmi de Wykliff or Johannes filius Simon de Wycliff, the first of whom was ordained acolyte on 18 December 1350, and both of whom were ordained subdeacon on 12 March 1351, deacon on 18 April 1351, and priest on 24 September 1351. This would suggest he was born in the mid-1320s."

After graduation John Wycliffe taught at Oxford University. He resigned in 1361 to take up the living of Fillingham, Lincolnshire. In 1362 he accepted the prebend of Aust, Gloucestershire, and in 1368 he became the curate of Ludgershall, Wiltshire.

John Wycliffe became a renown lecturer in theology and philosophy. On 26th July 1374, Wycliffe was appointed as one of five new envoys to continue negotiations in Bruges with papal officials over clerical taxes and provisions. The negotiations ended without conclusion, and the representatives of each side retired for further consultation. (3) It has been argued that the failure of these negotiations had a profound impact on his religious beliefs. "He began to attack Rome's control of the English Church and his stance became increasingly anti-Papal resulting in condemnation of his teachings and threats of excommunication."

John Wycliffe antagonized the orthodox Church by disputing transubstantiation, the doctrine that the bread and wine become the actual body and blood of Christ. Wycliffe developed a strong following and those who shared his beliefs became known as Lollards. They got their name from the word "lollen", which signifies to sing with a low voice. The term was applied to heretics because they were said to communicate their views in a low muttering voice.

In a petition later presented to Parliament, the Lollards claimed: "That the English priesthood derived from Rome, and pretending to a power superior to angels, is not that priesthood which Christ settled upon his apostles. That the enjoining of celibacy upon the clergy was the occasion of scandalous irregularities. That the pretended miracle of transubstantiation runs the greatest part of Christendom upon idolatry. That exorcism and benedictions pronounced over wine, bread, water, oil, wax, and incense, over the stones for the altar and the church walls, over the holy vestments, the mitre, the cross, and the pilgrim's staff, have more of necromancy than religion in them.... That pilgrimages, prayers, and offerings made to images and crosses have nothing of charity in them and are near akin to idolatry."

As one of the historians of this period of history, John Foxe, has pointed out: "Wycliffe, seeing Christ's gospel defiled by the errors and inventions of these bishops and monks, decided to do whatever he could to remedy the situation and teach people the truth. He took great pains to publicly declare that his only intention was to relieve the church of its idolatry, especially that concerning the sacrament of communion. This, of course, aroused the anger of the country's monks and friars, whose orders had grown wealthy through the sale of their ceremonies and from being paid for doing their duties. Soon their priests and bishops took up the outcry."

It is believed that Wycliffe and his followers began translating the Bible into English. Henry Knighton, the canon of St Mary's Abbey, Leicester, reported disapprovingly: "Christ delivered his gospel to the clergy and doctors of the church, that they might administer it to the laity and to weaker persons, according to the states of the times and the wants of men. But this Master John Wycliffe translated it out of Latin into English, and thus laid it out more open to the laity, and to women, who could read, than it had formerly been to the most learned of the clergy, even to those of them who had the best understanding. In this way the gospel-pearl is cast abroad, and trodden under foot of swine, and that which was before precious both to clergy and laity, is rendered, as it were, the common jest of both. The jewel of the church is turned into the sport of the people, and what had hitherto been the choice gift of the clergy and of divines, is made for ever common to the laity."

In September 1376, Wycliffe was summoned from Oxford by John of Gaunt to appear before the king's council. He was warned about his behaviour. Thomas Walsingham, a Benedictine monk at St Albans Abbey, reported that on 19th February, 1377, Wycliffe was told to appear before Archbishop Simon Sudbury and charged with seditious preaching. Anne Hudson has argued: "Wycliffe's teaching at this point seems to have offended on three matters: that the pope's excommunication was invalid, and that any priest, if he had power, could pronounce release as well as the pope; that kings and lords cannot grant anything perpetually to the church, since the lay powers can deprive erring clerics of their temporalities; that temporal lords in need could legitimately remove the wealth of possessioners." On 22nd May 1377, Pope Gregory XI issued five bulls condemning the views of John Wycliffe.

John Wycliffe tried to employ the Christian vision of justice to achieve social change: "It was through the teachings of Christ that men sought to change society, very often against the official priests and bishops in their wealth and pride, and the coercive powers of the Church itself." Barbara Tuchman has claimed that John Wycliffe was the first "modern man". She goes on to argue: "Seen through the telescope of history, he (Wycliffe) was the most significant Englishman of his time."

King Edward III had problems fighting what became known as the Hundred Years War. He achieved early victories at Crécy and Poitiers, but by 1370 the French won a succession of battles and were able to raid and loot towns on the south coast. Fighting the war was very expensive and in February 1377 the government introduced a poll-tax where four pence was to be taken from every man and woman over the age of fourteen. "This was a huge shock: taxation had never before been universal, and four pence was the equivalent of three days' labour to simple farmhands at the rates set in the Statute of Labourers".

King Edward died soon afterwards. His ten-year-old grandson, Richard II, was crowned in July 1377. John of Gaunt, Richard's uncle, took over much of the responsibility of government. He was closely associated with the new poll-tax and this made him very unpopular with the people. They were very angry as they considered the tax unfair as the poor had to pay the same tax as the wealthy. Despite this, the collectors of the tax seem not to have had to face more than an occasional, local disturbance.

In 1379 Richard II called a parliament to raise money to pay for the continuing war against the French. After much debate it was decided to impose another poll tax. This time it was to be a graduated tax, which meant that the richer you were, the more tax you paid. For example, the Duke of Lancaster and the Archbishop of Canterbury had to pay £6.13s.4d., the Bishop of London, 80 shillings, wealthy merchants, 20 shillings, but peasants were only charged 4d.

The proceeds of this tax was quickly spent on the war or absorbed by corruption. In 1380, Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury, suggested a new poll tax of three groats (one shilling) per head over the age of fifteen. "There was a maximum payment of twenty shillings from men whose families and households numbered more than twenty, thus ensuring that the rich payed less than the poor. A shilling was a considerable sum for a working man, almost a week's wages. A family might include old persons past work and other dependents, and the head of the family became liable for one shilling on each of their 'polls'. This was basically a tax on the labouring classes."

The peasants felt it was unfair that they should pay the same as the rich. They also did not feel that the tax was offering them any benefits. For example, the English government seemed to be unable to protect people living on the south coast from French raiders. Most peasants at this time only had an income of about one groat per week. This was especially a problem for large families. For many, the only way they could pay the tax was by selling their possessions. John Wycliffe gave a sermon where he argued: "Lords do wrong to poor men by unreasonable taxes... and they perish from hunger and thirst and cold, and their children also. And in this manner the lords eat and drink poor men's flesh and blood."

John Ball toured Kent giving sermons attacking the poll tax. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, heard about this he gave orders that Ball should not be allowed to preach in church. Ball responded by giving talks on village greens. The Archbishop now gave instructions that all people found listening to Ball's sermons should be punished. When this failed to work, Ball was arrested and in April 1381 he was sent to Maidstone Prison. At his trial it was claimed that Ball told the court he would be "released by twenty thousand armed men".

It has been claimed that the teachings of John Wycliffe influenced John Ball, a priest from Kent. For example, Thomas Walsingham a Benedictine monk at St Albans Abbey, stated that Ball "taught the people that tithes ought not be paid" and that he was preaching the "wicked doctrines of the disloyal John Wycliffe."

Some historians such as Charles Oman have disputed this claim because during his research failed to discover any evidence that Ball and his followers "showed any signs of Wycliffite tendencies". However, Reg Groves quotes Bishop William Courtenay as saying that Ball told him that he was a disciple of Wycliffe. R. B. Dobson has observed: "In their understandable reaction from the deliberately propagated legend that John Ball was John Wycliffe's disciple, historians… have sometimes unduly discounted a not unimportant connection between these two ideologues - that the audience for their respective messages must certainly have sometimes overlapped."

In June 1381, John Ball and Wat Tyler led a march to London. This became known as the Peasants' Revolt. On 14th June, Richard II agreed to the demands of the rebels. This included the end of all feudal services, the freedom to buy and sell all goods, and a free pardon for all offences committed during the rebellion. The following day, William Walworth, mayor of London, raised an army of about 5,000 men. Wat Tyler was murdered and the following month John Ball, was hung, drawn and quartered at St Albans.

John Wycliffe denied he was involved in the uprising but as John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984), has been pointed out: "At the popular level a distinction between religious and social radicalism is hard to make, and, if Ball can be taken as representative, the poor priests contributed an element of ideological radicalism to the revolt."

In 1382 John Wycliffe was condemned as a heretic and was forced into retirement. (24) Archbishop William Courtenay urged Parliament to pass a Statute of the Realm against preachers such as Wycliffe: "It is openly known that there are many evil persons within the realm, going from county to county, and from town to town, in certain habits, under dissimulation of great holiness, and without the licence ... or other sufficient authority, preaching daily not only in churches and churchyards, but also in markets, fairs, and other open places, where a great congregation of people is, many sermons, containing heresies and notorious errors."

John Wycliffe died in Ludgershall on 31st December, 1384. He was buried in the churchyard. Afraid that Wycliffe's grave would become a religious shrine, on the orders of Richard Fleming, bishop of Lincoln, acting on the instructions of Pope Martin V, officials exhumed the bones, burnt them, and scattered the ashes on the River Swift.

On this day in 1834 Mary Jane Stafford was born in Hyde Park, Vermont, on 31st December, 1834. When she was three years old Mary's family moved to Crete, Illinois. After leaving school she taught in Joliet, Shawneetown and Cairo.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War the Union Army arrived to protect Cairo from the Confederate Army. As the town was situated at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. A series of epidemic diseases broke out amongst the troops and Stafford volunteered her services as a nurse.

In the summer of 1861 Stafford began work with Mary Ann Bickerdyke at Fort Donelson. Stafford also served under General Ulysses S. Grant. at Shiloh in Tennessee. She also worked on the hospital ships, City of Memphis and Hazel Dell.

After the war Stafford was determined to become a doctor. She graduated from the Medical College for Women in New York in 1869. She also studied at the University of Breslaw in Germany, wher she performed the first ovariotomy ever done by a woman.

In 1872 Mary Jane Stafford opened a private practice in Chicago. Later she became professor of women's diseases at the Boston University School of Medicine and a staff doctor at the Massachusetts Homeopathic Hospital.She died on 8th December, 1891.

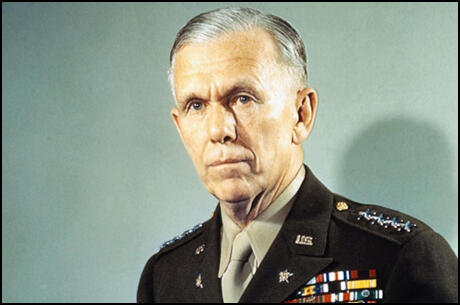

On this day in 1880 George Marshall was born in Uniontown, Pennsylvania. He graduated from Virginia Military Institute in 1901. The following year he received a commission as a second lieutenant and was sent to the Philippines. In 1906 Marshall resumed his education at Fort Leavenworth. He graduated top of the class and qualified for the Army Staff College. When he completed the course he was kept on for another two years as an instructor.

In the First World War Marshall served on the Western Front and was involved in the planning of the Meuse-Argonne offensive in 1918. Promoted to colonel Marshall served for five years as aide to General John Pershing (1919-24) and had a spell of duty in China (1924-27). This was followed by five years as an instructor at Fort Benning (1927-33).

In June 1933 Marshall was given command of the 8th Infantry and became responsible for 34 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in Georgia, Florida and South Carolina. Marshall was a strong believer in the CCC and argued that the US Army should fully support this social experiment.

Marshall was promoted to brigadier general in October, 1936, and was given command of the 5th Brigade at Vancouver Barracks in Washington. He was responsible for the CCC camps in the district. Soon afterwards he became seriously ill and had to have his thyroid gland removed. For a while it was believed that Marshall would have to be retired from the army but he eventually made a full recovery.

In August 1938, Marshall was appointed chief of the War Plans Division and three months later he became deputy Chief of Staff. This brought Marshall into contact with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and members of his administration. Harry Hopkins was especially impressed with Marshall and suggested to the president that he should become the new Chief of Staff. Roosevelt agreed and he assumed office in September 1939.

Marshall directed the United States armed forces throughout the Second World War. Over the next four years the US Army grew to a force of 8,300,000 men. Unlike his predecessor, Marshall was a strong advocate of air power and therefore got on well with General Henry Arnold. However he clashed with Admiral Ernest King over his policy of using all available resources to defeat Germany before Japan. As a result some critics have claimed that his actions prolonged the Pacific War.

In 1944 Marshall was disappointed not to have been given command of the Allied D-Day landings. However, Franklin D. Roosevelt argued that he could not afford to lose him as Chief of Staff. He was involved in the planning of the invasion and Winston Churchill later claimed that Marshall's achievements were monumental and described him as the "organizer of victory".

Marshall was given the rank of a five-star general in December 1944. Along with William Leahy he was senior to Ernest King, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur and Henry Arnold. Marshall resigned as Chief of Staff on 21st November, 1945, but a few days later Harry S. Truman persuaded him to become U.S. ambassador in China.

In January 1947, Truman, who called Marshall "the greatest living American", appointed him as his Secretary of State. While in this position, Marshall devised the European Recovery Program (ERP). Over the first year the ERP spent $5,300,000,000 and played a decisive role in the reconstruction of war-torn Europe.

In 1949, ill-health forced Marshall to resign from office and he was replaced by Dean Acheson. However, the following year, aged sixty-nine, Marshall accepted the post as Secretary of Defence and helped organize United States forces in the early stages of the Korean War.

In the summer of 1951 Marshall was attacked by Joe McCarthy, the right-wing senator from Wisconsin, as being soft on communism. In a speech that McCarthy gave on 14th June, he accused the Secretary of Defence of making decisions that "aided the Communist drive for world domination" and implied that he was a traitor to his country.

Disillusioned by the smear campaign, George Marshall retired from politics. However, Marshall's talents were appreciated abroad and in 1953 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace for his contribution to the recovery of Europe after the Second World War. George Marshall died in Washington on 16th October, 1959.

On this day in 1907 Michael Marks died. Marks was born in Slonim, Russia in 1859. As a young man Marks emigrated to England. Without a trade and unable to speak the English language, Marks moved to Leeds where there was a company called Barran that was known to employ Jewish refuges.

In 1884 Marks met Isaac Dewhurst, the owner of a warehouse in Leeds. The two men arranged a deal where Marks agreed to buy good from Dewhurst and to sell them in the numerous villages around Leeds. The venture was a success and Marks soon raised enough money to establish a stall in Leeds' open market. He also sold goods at Castleford and Wakefield markets.

Marks also decided to rent an area at the new covered market in Leeds that traded six days a week. On one of his stalls Marks sold goods that only cost one penny. Next to the stall was a big poster with the words: Don't Ask the Price, It's a Penny. Over the next few years Mark's opened similar penny stalls in covered market halls all over Yorkshire and Lancashire.

In 1894 Marks decided he needed a partner to help him expand the business. He approached Isaac Dewhurst who decided against the offer but suggested that his cashier, Tom Spencer, might be interested. Spencer had been watching the career of rMarks for sometime and considered the £300 required for a half-share in his business to be a good investment.

It was agreed that Spencer would manage the office and warehouse whereas Marks would continue to run the market stalls. Spencer, who had developed some important contacts while working for Isaac Dewhurst, was able to get the best prices for goods by dealing directly with the manufactures. With the help of Tom Spencer Marks was able to open stores in Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Middlesbrough, Sheffield, Bristol, Hull, Sunderland and Cardiff.

In 1897 Marks & Spencer built a new warehouse in Manchester. This now became the centre of their business empire that now included thirty-six branches. New stores had been built in Bradford, Leicester, Northampton, Preston, and Swansea. London had seven branches including those at Brixton, Kilburn, Islington and Tottenham.

In 1903 Marks & Spenser became a limited company. Spencer's £300 investment was now worth £15,000. Tom Spencer retired later that year but Michael Marks continued to develop the business. 1906 was a record year for the company with several stores taking over £4,000 a year. This included Liverpool (£9,857), Brixton (£9,766), Leeds (£8,701), Manchester (£8,459), Bristol (£6,242), Newcastle (£5,482), Hull (£4,513) and Middlesbrough (£4,064).

On this day in 1951 the Marshall Plan comes to an end. On 12th March, 1947, Harry S. Truman, announced details to Congress of what eventually became known as the Truman Doctrine. In his speech he pledged American support for "free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures". This speech also included a request that Congress agree to give military and economic aid to Greece in its fight against communism.

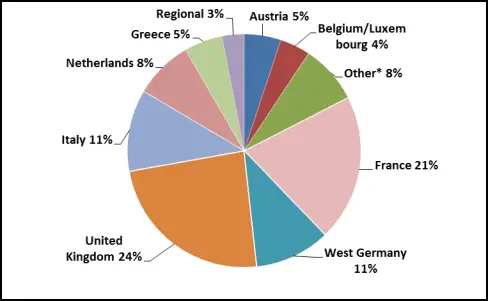

Three months later George C. Marshall, Truman's Secretary of State, announced details of what became known as the Marshall Plan or the European Recovery Program (ERP). Marshall offered American financial aid for a programme of European economic recovery. Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary, made it clear he fully supported the scheme but the idea was rejected by the Soviet Union. A conference was held in Paris in September and sixteen nations in Western Europe agreed on a four year recovery plan.

On 3rd April, 1948, Harry S. Truman signed the first appropriation bill authorizing $5,300,000,000 for the first year of the ERP. Paul G. Hoffman was appointed as head of the Organization for Economic Cooperation (OEEC) administration and by 1951 was able to report that industrial production in Western Europe had grown 30 per cent since the beginning of the Second World War.

The European Recovery Program came to an end on 31st December, 1951. It its three year existence, the ERP spent almost $12,500,000,000. It was succeeded by the Mutual Security Administration.

On this day in 2012 The Daily Mail: reported that Education Secretary Michael Gove has decreed that Mary Seacole should be taken out of the National Curriculum. Guy Walters wrote: "The £500,000 memorial - larger than the statue of Florence Nightingale near Pall Mall - will show Seacole marching out to the battlefield, a medical bag over her shoulder, a row of medals proudly pinned to her chest. There's just one problem: historians around the world are growing increasingly uneasy about the statue, amid claims the adulation of Seacole has gone too far. They claim her achievements have been hugely oversold for political reasons, and out of a commendable - but in this case misguided - desire to create positive black role models. Now Seacole is at the centre of a new controversy with the news that the story of her life will no longer be taught to thousands of pupils. Westminster Education Secretary Michael Gove has decreed that instead they will learn about traditional figures such as Oliver Cromwell and Winston Churchill."

Walters quoted Lynn MacDonald, a history professor and world expert on Florence Nightingale, who felt Seacole is being promoted at the expense of Nightingale. "Nightingale was the pioneer nurse, not Mary Seacole. It's fine to have a statue to whoever you want, but Seacole was not a pioneer nurse, she didn't call herself a nurse, she didn't practise nursing, and she had no association with St Thomas's or any other hospital."

Imran Kahn, an executive member of Conservative Muslim Forum and a former Conservative councillor, argued in New Statesman on 5th January, 2013: "According to newspaper reports, Mary Seacole is to be dropped from the national curriculum so history teachers can concentrate on Winston Churchill and Oliver Cromwell. Tellingly, teachers themselves have not been coming forward to offer support for this move. The idea that schools must silence black voices so teachers can talk about Churchill, Cromwell or Nelson is one that barely merits serious argument. But bearing in mind that the abolition of slavery occurred during the lifetime of Mary Seacole in 1840, and the gigantic military presence in the British West Indies – 93 infantry regiments serving between 1793 and 1815 – not to mention her own crucial role, Seacole is ideally placed to mark out hugely significant historical events. Michael Gove must trust teachers to decide what is in the best interests of children, instead of air-brushing black people out of history. There is no question that historical black role models such as Seacole give children of all races important tools in overcoming racist assumptions about black and Asian peoples’ contribution to Britain. Knowing about black history educates all of us, promotes respect and helps to inculcate shared multicultural values."

Opponents of the idea of removing Mary Seacole from the National Curriculum started an online petition: "The Government is proposing to remove Mary Seacole from the National Curriculum. We are opposed to this and wish to see Mary Seacole retained so that current and future generations can appreciate this important historical person. Her role in the Crimea War fully justifies Mary Seacole's status as a Victorian figure taught in schools today. She was a national heroine on her return to Britain and a crowd of 80,000 attended a four day fundraising benefit in her honour in 1857. Her inclusion on the National Curriculum came as a result of a tireless campaigning to recognise someone who had become a forgotten figure in modern times. Her proposed removal can only be attributed to a recent backlash against Mary Seacole as a symbol of 'political correctness' by Right-wing media and commentators. To remove Mary Seacole from the National Curriculum is tantamount to rewriting history to fit a worldview hostile to Britain's historical diversity.... Mary Seacole the only Black figure to feature in the National Curriculum not connected to civil rights or enslavement and removing someone who was voted by the public the Greatest Black Briton sends out the wrong signals. We should be taught more Black history not less."

The petition was signed by 35,000 people and The Independent reported on 7th February, 2013: "The 'greatest black Briton' Mary Seacole is to remain on the National Curriculum after an apparent U-turn by Education Secretary Michael Gove, The Independent has learned. The move represents a major victory for campaigners, who opposed his plans to drop her. The reprieve was granted under pressure from Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, as well as Operation Black Vote which set up a petition signed by more than 35,000 people. On the old Curriculum, Mary Seacole - who cared for soldiers during the Crimean War – appeared in the annex as suggested as someone primary school teachers could use in their classrooms to illustrate Victorian Britain. In the new document, her story is even more central. Seacole, one of the first and most prominent black figures in British history, appears alongside Florence Nightingale and Annie Besant as a figure high school pupils should cover in order to learn about."