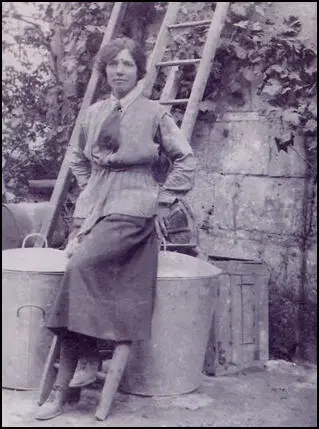

Mary Leigh

Mary Brown was born in Manchester in 1885. (1) She was a schoolteacher until her marriage to a builder named Leigh. According to Sylvia Pankhurst "a quiet, small man." (2)

In 1906 Leigh joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She was arrested for the first time in March 1907 when she took part in a deputation to the House of Commons. In court she annoyed the magistrates by unfurling a WSPU flag. She was sentenced to a month's imprisonment. (3)

On 30th June, 1908, Mary Leigh attended a public meeting in Parliament Square. The authorities decided to send in 5,000 foot police and 50 mounted men to break-up the meeting. Sylvia Pankhurst later reported: "Women spoke from the steps of the Government buildings and offices in Broad Sanctuary, they lifted themselves above the people by the railings round the Abbey Gardens and Palace Yard, or raised their voices standing among the crowds on road or pavement. They were torn by the harrying constables from their foothold and flung into the masses of people... Then roughs appeared, organized gangs, who treated the women with every type of indignity... I was obliged to drop my handbag with keys and purse, to have my hands free to protect myself. The roughs were constantly attempting to drag women down side streets away from the main body of the crowd... Enraged by the violence and indecency in the Square, Mary Leigh and Edith New took a cab into Downing Street, and flung two small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house." (4) It was later revealed that these gangs had been hired by Scotland Yard. (5)

Mary Leigh: WSPU Militant

The next day at Westminster police court twenty-seven women were sent to prison for terms varying from one to two months. Mary Leigh and Edith New, were sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. In court the women wore white dresses and were relieved to hear the sentence because they feared it would be a much longer sentence. However, the Manchester Guardian protested in a leading article: "Their stringent imprisonment... violates the public conscience." (6) However, Millicent Fawcett, leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), said later that it was this incident that resulted in her condemning the methods being used by the WSPU. (7)

When the two women were released on 23rd August, 1908, they were greeted by a brass band playing "The Marseillaise". The woman who met them wore white dresses with belts, sashes and hats in the suffragette colours, and the wagon that carried Leigh and New was hauled by twelve suffragettes. They were taken to Queen's Hall in Langham Place where they were given breakfast by the two main leaders of the WSPU, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. (8)

from Holloway to Queen's Hall on 23rd August 1908.

On 13th October 1908 she took part in another protest meeting outside the House of Commons . Cordons of police, five feet deep, were drawn across all the approaches to Parliament Square. Police horses were also used against the women. "mary Leigh flung herself upon the horsemen, seizing a bridle in either hand." (9) Leigh was arrested and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment. That year, she spent more than a total of six months in prison. (10)

On 14th January 1909, the WSPU presented Emmeline Pankhurst with an amethyst, pearl and emerald necklace at the Queen's Hall. (11) Mary Leigh was given a clock in recognition of her work for the WSPU: "Incommemoration of the year 1908, when for taking part in public demonstrations of protest against the political subjection of women, she was sentenced three times to terms of imprisonment amounting to more than six months' incarceration in Holloway, she won by her brave spirit and cheerful endurance the admiration and esteem of all her comrades in the votes for women agitation." Leigh was unable to be at the ceremony but sent a message: "It will always be a pleasure to me. It is something I can hand down with pride. My absence this evening is a grief it would be impossible to exaggerate." (12)

In May 1909, Mary Leigh was appointed drum major of the newly-founded purple, white and green WSPU Drum and Fife Band which was introduced to publicize the Women's Exhibition at the Prince's Skating Rink. (13) Fifty stalls were loaded with farm produce, sweets, dresses, badges and jewellery. The event raised £5,664 for the campaign fund. (14) The success of the band enabled the WSPU to pay Leigh a £1 a week, a decent wage at the time. (15)

On 25th June 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: "I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction." (16)

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London's Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail". (17)

Hunger Strikes and Force-Feeding

Mary Leigh, Bertha Brewster, Rona Robinson and Theresa Garnett, rented a house close to Sun Hall in Liverpool. On 20th August 1909, the women interrupted a speech made by Richard Haldane the Secretary of State for War. The women climbed onto the roof and Leigh addressed the gathering crowd. The Times described Leigh as "a frail little figure of a woman". (18)

The Liverpool Courier reported that the women "threw bricks and stones through the windows of the Sun Hall with a dexterity which was nothing short of marvellous". (19) After more windows were smashed the police found a window cleaner to get the women down but his ladder was too short and the fire brigade were called. Eventually they managed to bring down the seven women off the roof "in a perilous descent." (20)

Leigh was arrested and was sentenced to two months in prison. On their way to Walton Gaol the women sang "The Marseillaise", broke the windows of the Black Maria and pushed a "Votes for Women" flag through the ventilator in the roof. The governor of the prison sat alongside the driver, and four policemen rode on the step of the van. (21)

The Liverpool Post commented: "Seven viragos have given a lesson to the country which it will not be slow to profit by, and we trust that the arm of outraged justice administer to them a lesson which they will not soon forget." (22) Bertha was sentenced to one month in prison, whereas the other participants received two months. Bertha protested at the leniency of her sentence which she served at Walton Gaol. The women immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. The women were released on 26th August. (23)

On 22nd September 1909 Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth, Mabel Capper, Patricia Woodcock and Rona Robinson conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work." (24)

The Freeman's Journal reported: "Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand. Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck. A policeman who climbed on the roof – a hazardous undertaking – found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: 'Come on up at your peril,' the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest." (25)

Leigh got four months's imprisonment, Marsh three months, the others from a month to fourteen days. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force. (26)

Mary Leigh, described what it was like to be force-fed: "On Saturday afternoon the wardress forced me onto the bed and two doctors came in. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternative days. The sensation is most painful - the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down - about a pint of milk... egg and milk is sometimes used." (27)

Leigh's graphic account of the horrors of forcible feeding was published in Votes for Women, while she was still in prison. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. (28) All the women were released over the next three days "owing to their emaciated condition". (29)

On her release Leigh sued Herbert Gladstone, the Home Secretary. In court on 9th December, 1909, Leigh pointed out that she had been handcuffed for over thirty hours, the hands fastened behind during the day and in front with the palms outward at night. Only when the wrists had become intensely painful and swollen were the irons removed. On the fourth day of her fast, the doctor told her that she must either abandon the hunger strike or be fed by force. She protested that forcible feeding was an operation, and as such could be performed without a sane patient's consent; but she was seized by the wardresses and the doctor administered food by the nasal tube. The Lord Chief Justice ruled that it was the duty of the prison medical officer to prevent the prisoner from committing suicide. (30)

Hunger-strikes now became the accepted strategy of the WSPU. In one eighteen month period, Emmeline Pankhurst endured ten hunger-strikes. She later recalled: "Hunger-striking reduces a prisoner's weight very quickly, but thirst-striking reduces weight so alarmingly fast that prison doctors were at first thrown into absolute panic of fright. Later they became somewhat hardened, but even now they regard the thirst-strike with terror. I am not sure that I can convey to the reader the effect of days spent without a single drop of water taken into the system. The body cannot endure loss of moisture. It cries out in protest with every nerve. The muscles waste, the skin becomes shrunken and flabby, the facial appearance alters horribly, all these outward symptoms being eloquent of the acute suffering of the entire physical being. Every natural function is, of course, suspended, and the poisons which are unable to pass out of the body are retained and absorbed." (31)

On 18th November 1910, Leigh took part in a demonstration at 10 Downing Street against the failure of Herbert Asquith and his government to pass legislation to give women the vote. Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested. (32) This included Leigh, Eileen Casey, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Clara Giveen, Ada Wright, Lilian Dove-Wilcox and Grace Roe. (33)

Mary Leigh was released without charge but in 1911 she was back in prison for not paying her dog licence (tax) and was sentenced to two months in prison. Lady Constance Lytton had only received a two-week sentence for the same offence. Elizabeth Crawford has argued that this highlighted "the government's differing treatment of working class women compared to wealthy women with influence and often political connections." (34)

Militant Action in Dublin

On 16th July, 1912, Gladys Evans and Jennie Baines caught a boat from Holyhead to Dublin and took lodgings in Lower Mount Street. Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper arrived two days later. They were in the city because Herbert Asquith was to give a speech on Home Rule to 4,000 supporters. On the 18th July, Leigh saw Asquith travelling in an open carriage with John Redmond and the Lord Mayor of Dublin. She hurled a hatchet at Asquith, but missed him and hit Redmond on his ear. (35)

According to John O'Brien, the Chief Marshall: "When abreast of Prince's Street he saw an article flung from the opposite side. He ran round by the horses' head and saw the accused (Mary Leigh) holding on to one of the rails of the carriage. He saw the accused throw the article. He pulled her away from the carriage, when she counteracted him, and started to poke him and tear at him, and struck him a couple of blows in the face." (36)

Leigh was able to escape and that night, along with Gladys Evans attended a production of the Theatre Royal. As the audience was leaving Joseph Keoth noticed a woman (Evans) throwing a burning rag soaked in paraffin into the projection box at the back of the stalls and running away as if she "expected some explosion". Evans then chucked a handbag filled with gunpowder and matches into a box near the stage. Leigh also threw a burning chair into the orchestra pit. "Several small explosions occurred, produced by amateur bombs made of tin canisters, which, with bottles of petrol and benzine, were afterwards found lying about." (37)

Evans was arrested at the scene and Leigh at her lodgings the next morning. Jennie Baines and Mabel Capper were also taken into custody. The four women were charged with having "unlawfully conspired with other persons, known, and unknown, to inflict grievous bodily harm and wilful and malicious damage upon property, and to cause an explosion in the Theatre Royal of a nature likely to endanger life or to cause serious injury to property; and that in pursuance of this object they attempted to set fire to the theatre." (38)

Mary Leigh called no witnesses and addressed the jury from the dock. Votes for Women reported: "The dramatic feature of the day was undoubtedly Mrs Leigh's defence of her case. Slight and frail in outward appearance, spontaneous and alert in manner, she seemed strangely out of place among the burly officials and dull routine of a court of justice. Her masterly cross-examination was so searching as seriously to baffle several witnesses and confuse their evidence on the point of identification, so that the jury found themselves unable to agree that she actually was one of the persons who fired the Theatre Royal. Her speech to the Court was a heroic effort. It was not rhetoric, nor careful arrangements of arguments and telling points, nor even eloquence, that moved the hearts so strongly of all who gazed upon her pleading countenance as she laboured to reiterate the long tale of injustice and evasion meted out to the women who asked for the removal of the disqualification of their sex, and the equally long tale of the steadily successful attainment by men of their political objects in England and Ireland by the sole means of agitation by violence. The pathos of her passionate determination to persevere in her efforts to the emancipation of her womanhood moved the judge himself and many other with deep emotion. Her courage was an amazement even to women who have felt most deeply the things we have at heart." The judge referred to Mary Leigh as "a very remarkable lady of great talents" (39)

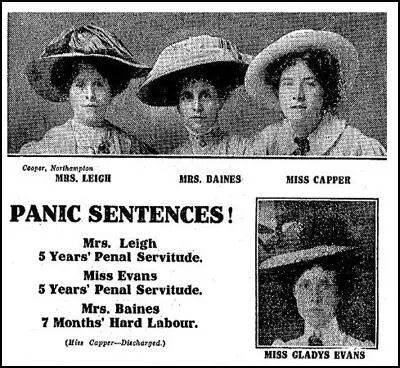

Mary Leigh told them that if they sent her to prison she might not survive the sentence. Mary warned that if convicted she would fight: "she would put her back against the wall, and nothing, not even the whole army of the Government and officials, would bring her to submission. The jury returned guilty verdicts on Mary Leigh and Gladys Evans. Both women were sent to prison for five years because "no more terrible catastrophe could occur in a city than a conflagration at a theatre". Jennie Baines was sentenced to seven months with hard labour, and Mabel Capper was acquitted for lack of evidence." (40)

The women went on hunger-strike. On 7th August Mary Leigh weighed ninety-five pounds, and Gladys Evans a hundred and fourteen pounds. Before they were force-fed for the first time, their weight had fallen to ninety and ninety-six pounds respectively. After a week Mary's weight had dropped to eighty-six pounds and Gladys had lost only half a pound. Despite having been fed three times a day, Mary had lost ten pounds in eighteen days and the authorities feared that she would die. (41)

Leigh was released on licence on 20th September 1912 weighing five stones and four pounds.: "When the medical report was received by the Prison Board regarding the grave condition of Mrs Leigh's health, a consultation took place, the Attorney-General being called in. After a long consultation the Board, with the approval of the Attorney-General, recommended her release, and the Lords Junction of the Privy Council, in the absence of the Lord Lieutenant, made the necessary order. The release took place at 6.30 pm. It was the intention to have her removed to the Mater Hospital, but she was conveyed in a cab by two lady friends to a private residence. She is in a state of almost complete collapse, and a specialist will be called in today. Miss Gladys Evans, her fellow-prisoner, who is also being forcibly fed, was examined likewise, but as her condition has not become so far debilitated, no order was made in respect of her. In Mrs. Leigh's case, she had acquired the power of vomiting the food as soon as administered, and her debilitation was due to the consequent starvation." (42)

As soon as she recovered she began a campaign to get Gladys Evans released: "Mrs Mary Leigh, the suffragette who was released from Mountjoy Convict Prison last week after a hunger strike, sent a letter to a suffragette meeting in Dublin on Sunday stating that if her fellow-prisoner, Miss Gladys Evans, who had been sentenced to five years's penal servitude, is not released during the next few days she (Mrs Leigh) would lead a march on Mountjoy Prison, and the issue would only be decided by victory or death." (43)

The health of Gladys Evans began to give the authorities concern. Her heartbeat became irregular and she showed signs of "great nervous tension and general breakdown." She also began to resist the feeding process. It was reported she "violently resisted all efforts that were made to feed her and struggled very much". Five wardresses were needed to overcome her, and she had to be strapped by the ankles and wrists into the feeding chair. Evans was released on licence on 3rd October on medical grounds, after fifty-eight days of hunger-striking and being fed by stomach tube eighty-eight times. (44)

East London Federation of Suffragettes

Like other members of the WSPU, Mary Leigh began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. Leigh now joined the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF), an organization formed by Sylvia Pankhurst. In October 1913 Leigh was badly injured during scuffles with the police at an ELF meeting at Bow Baths. (45)

During the First World War she applied for war service, but was rejected because of her criminal record. Using her maiden name, Brown, she gained a place on an RAC course to train as an ambulance driver. Later she worked at the New Zealand Expeditionary Force Hospital in Surrey. (46)

After the war Mary Leigh joined the Labour Party and every year she made the pilgrimage to Morpeth, Northumberland, to tend the grave of Emily Wilding Davison. She continued to campaign for the vote for women after the passing of the limited 1918 Qualification of Women Act. In 1921, while being arrested for chalking the pavement advertising a meeting, she gave a policeman a black eye and went to prison. (47)

According to her biographer, Michelle Myall: "She apparently took part in the first Aldermaston march (1958), and as a committed socialist regularly attended the May day processions in Hyde Park. She was a founder of the Emily Wilding Davison lodge, a memorial to her suffrage comrade who died after throwing herself under the hooves of the king's horse at the 1913 Epsom Derby. Every year Mary Leigh made the pilgrimage to Morpeth, Northumberland, to tend Davison's grave. In later years she continued to recall with pride her days in the WSPU, and stood by her actions as a suffragette." (48)

Mary Leigh died in Stockport in 1979.

Primary Sources

(1) Mary Leigh was forced-fed in September, 1909. The WSPU was able to get her account published in a pamphlet while she was still in prison.

I was then surrounded and forced back onto the chair, which was tilted backward. There were about ten persons around me. The doctor then forced my mouth so as to form a pouch, and held me while one of the wardresses poured some liquid from a spoon; it was milk and brandy. After giving me what he thought was sufficient, he sprinkled me with eau de cologne, and wardresses then escorted me to another cell on the first floor, where I remained two days. On Saturday afternoon the wardresses forced me onto the bed and the two doctors came in with them. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternate days. Great pain is experienced during the process, both mental and physical. One doctor inserted the end up my nostril white I was held down by the wardresses, during which process they must have seen my pain, for the other doctor interfered (the matron and two of the wardresses were in tears), and they stopped and resorted to feeding me by the spoon, as in the morning. More eau dc cologne was used. The food was milk. I was then put to bed in the cell, which is a punishment cell on the first floor. The doctor felt my pulse and asked me to take food each time, but I refused.

On Sunday he came in and implored me to lie amenable and have food in the proper way. I still refused. I was fed by the spoon up to Saturday, October 2, three times a day. From four to five wardresses and the two doctors were present on each occasion. Each time the same doctor forced my mouth, while the other doctor assisted, holding my nose on nearly every occasion. On Monday, September 27, I was taken to a hospital cell, where I was fed by spoon in similar fashion. On Tuesday, the twenty-eighth, a feeding cup was used for the first time, and Benger's Food poured into my mouth for breakfast and supper, and beef-tea mid-day.

On Tuesday afternoon I overheard Miss Edwards, on issuing from the padded cell opposite, call out, "Locked in a padded cell since Sunday." I called out to her, but she was rushed into it. I then applied (Tuesday afternoon) to see the visiting magistrates. I saw them, and wished to know if one of our women was in a padded cell, and, if so, said she must be allowed out. I knew she had a weak heart and was susceptible to excitement, and it would be very bad for her if kept there longer. I was told no prisoner could interfere on behalf of another; any complaint on my own behalf would be listened to. I then said this protest of mine must be made on behalf of this prisoner, and if they had no authority to intervene on her behalf, it was no use applying to them for anything. After they had gone I made my protest by breaking eleven panes in my hospital cell. I was then fed in the same way by the feeding cup and taken to the padded cell, where I was stripped of all clothing and a night dress and bed given to me. As they took Miss Edwards out they put me into her bed, which was still warm. The cell is lined with some padded stuff-india-rubber or something. There was no air, and it was suffocating. This was on Tuesday evening.

I remained there until the Wednesday evening, still being fed by force. I was then taken back to the same hospital cell, and remained there until Saturday, October 2, noon, feeding being continued in the same way. On Saturday, October 2, about dinner time, I determined on stronger measures by barricading my cell. I piled my bed, table, and chair by jamming them together against the door. They had to bring some men warders to get in with iron staves. I kept them at bay about three hours. They threatened to use the fire hose. They used all sorts of threats of punishment. When they got in, the chief warder threatened me and tried to provoke me to violence. The wardresses were there, and he had no business to enter my cell, much less to use the threatening attitude. I was again placed in the padded cell, where I remained until Saturday evening. I still refused food, and I was allowed to starve until Sunday noon. Food was brought, but not forced during that interval.

Sunday noon, four wardresses and two doctors entered my cell and forcibly fed me by the tube through the nostrils with milk. Sunday evening, I was also fed through the nostril. I remained in the padded cell until Monday evening, October 4. Since then I have been fed through the nostril twice a day.

The sensation is most painful - the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down - about a pint of milk... egg and milk is sometimes used.

(2) Votes for Women (9th August 1912)

Mr T. M. Healy, KC, appeared for all the prisoners except Mrs Leigh, who conducted her own case, and addressed the jury at considerable length on the woman's suffrage movement, pointing out that women had tried constitutional methods, which had failed, and contending that the case against her had not been proved. The judge referred to her as "a very remarkable lady of great talents" ….

In his fine and impassioned speech for the defence of Miss Gladys Evans, he (Tim Healey) was rankly contemptuous of the trifling quantity of the damage to a couple of curtains, a carpet, and two chairs, only in comparison with the vaster outrages committed by the forerunners of the present-day electors, but with a greater and still more powerful emphasis, in comparison with the daily and hourly destruction of women's and children's lives in the cities of our civilisation.

Magnificent as was the plea of Mr Healy, the dramatic feature of the day was undoubtedly Mrs Leigh's defence of her case. Slight and frail in outward appearance, spontaneous and alert in manner, she seemed strangely out of place among the burly officials and dull routine of a court of justice. Her masterly cross-examination was so searching as seriously to baffle several witnesses and confuse their evidence on the point of identification, so that the jury found themselves unable to agree that she actually was one of the persons who fired the Theatre Royal. Her speech to the Court was a heroic effort. It was not rhetoric, nor careful arrangements of arguments and telling points, nor even eloquence, that moved the hearts so strongly of all who gazed upon her pleading countenance as she laboured to reiterate the long tale of injustice and evasion meted out to the women who asked for the removal of the disqualification of their sex, and the equally long tale of the steadily successful attainment by men of their political objects in England and Ireland by the sole means of agitation by violence. The pathos of her passionate determination to persevere in her efforts to the emancipation of her womanhood moved the judge himself and many other with deep emotion. Her courage was an amazement even to women who have felt most deeply the things we have at heart.

(3) Irish Independent (21 September 1912)

When the medical report was received by the Prison Board regarding the grave condition of Mrs Leigh's health, a consultation took place, the Attorney-General being called in. After a long consultation the Board, with the approval of the Attorney-General, recommended her release, and the Lords Junction of the Privy Council, in the absence of the Lord Lieutenant, made the necessary order.

The release took place at 6.30 pm. It was the intention to have her removed to the Mater Hospital, but she was conveyed in a cab by two lady friends to a private residence. She is in a state of almost complete collapse, and a specialist will be called in today.

Miss Gladys Evans, her fellow-prisoner, who is also being forcibly fed, was examined likewise, but as her condition has not become so far debilitated, no order was made in respect of her. In Mrs. Leigh's case, she had acquired the power of vomiting the food as soon as administered, and her debilitation was due to the consequent starvation.

(4) The Daily Mirror (21 September 1912)

After a hunger strike lasting forty-four days, Mrs Mary Leigh, the English suffragette who was sentenced on August 7 – six weeks ago – to five years' penal servitude for attempting to burn the Theatre Royal, Dublin, at the time of Mr. Asquith's visit, was released on licence yesterday evening from the Mountjoy Prison. This practically amounts to a total discharge; the remainder of her sentence being cancelled.

She had refused to take her food and had been subjected to the "forcible feeding" process, and her state of health become so serious that her medical attendant and the prison doctor, in consultation with Sir Christopher Nixon and Sir Thomas Myles, advised the authorities to release her.

Mrs Leigh was very emaciated after the hunger strike, and had to be lifted from a taxicab into an invalid chair...

Mrs Leigh is the suffragette who in December, 1909, after a hunger strike in Winston Green Prison, Birmingham, unsuccessfully sued the Home Secretary (then Mr Gladstone) for damages for a series of assaults in consequence of the forcible feeding treatment to which she was subjected.

(5) Derby Daily Telegraph (23 September 1912)

Mrs Mary Leigh, the suffragette who was released from Mountjoy Convict Prison last week after a hunger strike, sent a letter to a suffragette meeting in Dublin on Sunday stating that if her fellow-prisoner, Miss Gladys Evans, who had been sentenced to five years's penal servitude, is not released during the next few days she (Mrs Leigh) would lead a march on Mountjoy Prison, and the issue would only be decided by victory or death.

(6) Derby Advertiser and Journal (27 September 1912)

Mrs Mary Leigh, the Suffragette who, on August 8 last, was sentenced, along with Gladys Evans, to five years penal servitude on a charge of setting fire to the Theatre Royal, Dublin, was on Friday released from Mountjoy Prison, Dublin. She had been practising the hunger strike, and was so emaciated that she had to be lifted from the taxi-cab in an invalid chair at the private house to which she was taken.

(7) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931)

Mary Leigh and her colleagues, who were organising there, began by copying the police methods so far as to address a warning to the public not to attend Mr. Asquith's meeting, as disturbances were likely to ensue, and immediately the authorities were seized with panic. A great tarpaulin was stretched across the glass roof of the Bingley Hall, a tall fire escape was placed on each side of the building, and hundreds of yards of firemen's hoses were laid across the roof. Wooden barriers, nine feet high, were erected along the station platform and across all the leading thoroughfares in the neighbourhood, whilst the ends of the streets both in front and at the back of Bingley Hall were sealed up by barricades. Nevertheless, inside those very sealed-up streets, numbers of Suffragettes had been lodging for days past and were quietly watching the arrangements.

When Mr. Asquith left the House of Commons for his special train, detectives and policemen hemmed him in on every side, and when he arrived at the station in Birmingham, he was smuggled to the Queen's Hotel by a back subway a quarter of a mile in length and carried up in a luggage lift.

Meanwhile, tremendous crowds were thronging the streets and the ticket holders were watched as closely as spies in time of war. They had to pass four barriers and were squeezed through them by a tiny gangway and then passed between long lines of police and amid an incessant roar of "show your ticket." The vast throngs of people who had no tickets and had only come out to see the show surged against the barriers like great human waves, and occasionally cries of "Votes for Women" were greeted with deafening cheers.

Inside the hall there were armies of stewards and groups of police at every turn. The meeting began by the singing of a song of freedom led by a band of trumpeters. Then the Prime Minister appeared. "For years past the people have been beguiled with unfulfilled promises," he declared, but during his speech he was again and again reminded, by men, of the unfulfilled promises which had been made to women; and, though men who interrupted him on other subjects were never interfered with, these champions of the Suffragettes were, in every case, set upon with a violence which was described by onlookers as "revengeful" and "vicious." Thirteen men were maltreated in this way.

Meanwhile, amid the vast crowds outside women were fighting for their freedom. Cabinet Ministers had sneered at them and taunted them with not being able to use physical force. "Working men have flung open the franchise door at which the ladies are scratching," Mr. John Burns had said. So now they were showing that, if they would, they could use violence, though they were determined that, at any rate as yet, they would hurt no one. Again and again they charged the barricades, one woman with a hatchet in her hand, and the friendly people always pressed forward with them. In spite of a thousand police the first barrier was many times thrown down. Whenever a woman was arrested the crowd struggled to secure her release, and over and over again they were successful, one woman being snatched from the constables no fewer than seven times.

Inside the hall Mr. Asquith had not only the men to contend with, for the meeting had not long been in progress when there was a sudden sound of splintering glass and a woman's voice was heard loudly denouncing the Government. A missile had been thrown through one of the ventilators by a number of Suffragettes from an open window in a house opposite. The police rushed to the house door, burst it open, and scrambled up the stairs, falling over each other in their haste to reach the women, and then dragged them down and flung them into the street, where they were immediately placed under arrest. Even whilst this was happening there burst upon the air the sound of an electric motor horn which issued from another house near by. Evidently there were Suffragettes there too. The front door of this house was barricaded and so also was the door of the room in which the women were, but the infuriated Liberal stewards forced their way through and wrested the instrument from the woman's hands.

No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl beside her (Charlotte Marsh). Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work. A ladder was produced and the men prepared to mount it, but the only reply was a warning to "he careful" and all present felt that discretion was the better part of valour. Then the fire hose was dragged forward, but the firemen refused to turn it on, and so the police themselves played it on the women until they were drenched to the skin. The slates had now become terribly slippery, and the women were in great danger of sliding from the steep roof, but they had already taken off their shoes and so contrived to retain a foothold, and without intermission they continued "firing" slates. Finding that water had no power to subdue them, their opponents retaliated by throwing bricks and stones up at the two women, but, instead of trying, as they had done, to avoid hitting, the men took good aim at them and soon blood was running, down the face of the tall girl, Charlotte Marsh, and both had been struck several times.

At last Mr. Asquith had said his say and came hurrying out of the building. A slate was hurled at the back of his car as it drove away, and then "firing" ceased from the roof, for the Cabinet Minister was gone. Seeing that they now had nothing to fear the police at once placed a ladder against the house and scrambled up to bring the Suffragettes down, and then, without allowing them to put on their shoes, they marched them through the streets, in their stockinged feet, the blood streaming from their wounds and their wet garments clinging to their limbs. At the police station bail was refused and the two women were sent to the cells to pass the night in their drenched clothing.

We knew that Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, and their comrades in the Birmingham prison would carry out the hunger-strike, and, on the following Friday, September 24, reports appeared in the Press that the Government had resorted to the horrible expedient of feeding them by force by means of a tube passed into the stomach. Filled with concern, the committee of the Women's Social and Political Union at once applied both to the prison and to the Home Office to know if this were true but all information was refused.

(8) Freeman's Journal (12 December 1912)

Mr John O'Brien said that he was the Chief Marshall at the reception of Mr Asquith on his arrival in Dublin, on Thursday night, the 18th July. He was on the right-hand side of the carriage which contained Mr. Asquith, Mrs Asquith, Mr Redmond, and the Lord Mayor of Dublin. When abreast of Prince's Street he saw an article flung from the opposite side. He ran round by the horses' head and saw the accused holding on to one of the rails of the carriage. He saw the accused throw the article. He pulled her away from the carriage, when she counteracted him, and started to poke him and tear at him, and struck him a couple of blows in the face…

Prisoner, in conclusion, said if women got what she called a recognition of their rights they would be agreeable as the Irish people to call for cheers for Mr Asquith, and "even ask God to give him a long life."

(9) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931)

When Asquith visited Dublin, on July 18, Irish suffragists met him by boat at Kingstown, and shouted to him through megaphones. They rained Votes for Women confetti upon him from an tipper window as he and Redmond were conducted in torchlight procession through the streets, but when they attempted poster parades and an open-air meeting close to the hall where he was speaking, a mob attacked them with extraordinary violence. Countess Markievicz and others were hurt; every woman who happened to be in the streets was assailed. Many unconnected with the movement had to take refuge in shops and houses. The Ancient Order of Hibernians was abroad, determined to punish womanhood for the acts of militant women from England. Mary Leigh had rushed to the carriage in which John Redmond and the Prime Minister were riding and had dropped into it a small hatchet. She was mobbed, but escaped, and afterward she and Gladys Evans had made a spectacular show of setting fire to the Theatre Royal, where Asquith was to speak. They had attended a performance at the theatre, and as the audience was dispersing, Mary Leigh, in full view of numbers of persons, had poured petrol onto the curtains of a box and set fire to them, then flung a flaming chair over the edge of the box into the orchestra. Gladys Evans set a carpet alight, then rushed to the cinema box, threw in a little handbag filled with gunpowder, struck matches, and dropped them in after it. Finding they all went out as they fell, she attempted to get tinder the wire fencing into the box. Several small explosions occurred, produced by amateur bombs made of tin canisters, which, with bottles of petrol and benzine, were afterward found lying about.

Declaring it his duty to pass a sentence calculated to have a deterrent effect, Justice Madden sentenced both Mary Leigh and Gladys Evans to five years' penal servitude. He expressed the hope that when militancy were discontinued the term would he reduced. "It will have no deterrent effect upon us," responded Mary Leigh in defiant tones.

(10) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931)

On reaching London we at once summoned a general meeting of the Federation. The members at first declared they would not be "thrown out" of the W.S.P.U., nor would they agree to a change of name. I persuaded them at last that refusal would open the door to acrimonious discussions, which would hinder our work and deflect attention from the cause. The name of our organisation was then debated. The East London Federation of the Suffragettes was suggested by someone, and at once accepted with enthusiasm. I took no part in the decision. Our colours were to be the old purple, white, and green, with the addition of red - no change, as a matter of fact, for we had already adopted the red caps of liberty. Mother, annoyed by our choice of name, hastened down to the East End to expostulate; she probably anticipated objections from Paris. "We are the Suffragettes! that is the name we are always known by," she protested, "and there will be the same confusion as before!" I told her the members had decided it, and I would not interfere.

In the East End, with its miserable housing, its ill-paid casual employment and harsh privations bravely borne by masses of toilers, life wore another aspect. The yoke of poverty oppressing all was a factor no one-sided propaganda could disregard. The women speakers who rose up from the slums were struggling, day in, day out, with the ills which to others were merely hearsay. Sometimes a group of them went with me to the drawing-rooms of Kensington and Mayfair; their speeches made a startling impression upon those women of another world, to whom hard manual toil and the lack of necessaries were unknown. Many of the W.S.P.U. speakers came down to us as before: Mary Leigh, Amy Hicks, Theodora Bonwick, Mary Paterson, Mrs. Bouvier, that brave, persistent Russian, and many others; but it was from our own East End speakers that our movement took its life. There was wise, logical Charlotte Drake of Custom House, who, left an orphan with young brothers and sisters, had worked both as barmaid and sewing machinist, and who recorded in her clear memory incidents, curious, humorous, and tragic, which stirred her East End audiences by their truth.

Melvina Walker was born in Jersey and had been a lady's maid; many a racy story could she tell of the insight into "High Life" she had gained in that capacity. For a long period she was one of the most popular open-air speakers in any movement in London. She seemed to me like a woman of the French Revolution. I could imagine her on the barricades, waving the bonnet rouge, and urging on the fighters with impassioned cries. When she was in the full flood of her oratory, she appeared the very embodiment of toiling, famine-ridden, proletarian womanhood.

Mrs. Schlette, a sturdy old dame, well on in her sixties, came forward to make a maiden oration without hesitation, and soon was able to hold huge crowds for an hour and a half at a stretch. Mrs. Cressell, afterward a Borough Councillor; Florence Buchan, a young girl discharged from a jam factory, the reason being given by the forewoman: "What do you want to kick up a disturbance of a night with the Suffragettes"; Mrs. Pascoe, one of our prisoners, supporting by charring and home work a tubercular husband and an orphan boy she had adopted-but a few of the many who learnt to voice their claims.