Water Transport

In the 18th century, Francis Egerton, the Duke of Bridgewater owned a large coal-mine at Worsley. The main market for his coal was the fast-growing town of Manchester. The roads between Worsley and Manchester were so bad that Bridgewater had to use pack-horses instead of wagons. As each horse could only carry 3 hundredweight (cwt) of coal at a time, this was a very expensive form of transportation. (1)

In 1759, John Gilbert, one of Bridgewater's workers, suggested that a solution to this problem would be to cut a canal between Worsley Colliery and Manchester. Gilbert pointed out, that one horse could pull over 400 cwt of coal at a time when it was carried on a barge. Bridgewater liked the idea, and after gaining permission from Parliament gave instructions for the building of the Bridgewater Canal. (2)

Gavin Weightman, the author of The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007), has argued: "As there had been no tradition of canal-building before the 1750s, the engineers who took on the task had to learn new engineering skills - surveying the ground, determining the best course for the water and planning where locks and tunnels might be needed. In the eighteenth century the experts in the use of large-scale machinery were mostly millwrights - it was they who knew about cogs and gears and harnessing water power." (3)

Bridgewater Canal

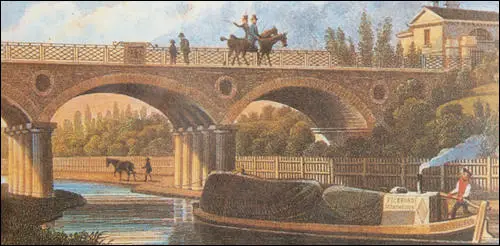

Bridgewater employed the talented engineer and millwright, James Brindley, to take charge of the project. Brindley was the obvious person to recruit for the project. He was not only a millwright but someone who had some knowledge of canals. It took Brindley eighteen months to build the ten-mile canal. To keep it level it had to be taken through tunnels, along newly raised embankments, and along aqueducts such as the two hundred-yard stretch of Barton Bridge above the River Irwell. (4) Its arch was built of masonry and it carried a layer of puddled clay, four feet thick, in order to waterprrof the bed of the canal. It was described as "one of the wonders of the age". (5) According to the record books Brindley was paid 2s.6d. a day for his work, but by the end of the project it was raised to 3s.6d. a day. (6)

Bridgewater now extended his canal to the Mersey. This provided Manchester manufacturers with an alternative way of transporting their goods to the port of Liverpool. As this reduced the costs of transporting goods between these two cities from 12s to 6s a ton (20 cwt), Bridgewater had little difficulty in persuading people to use his canal. It was a "powerful signal regarding the profitability and feasibility of canals". (7)

Samuel Smiles has argued that along with James Watt, Bridgewater "contributed to lay the foundations of the prosperity of Manchester and Liverpool... the cutting of the canal from Worsley to Manchester gave that town the immediate benefit of a cheap and abundant supply of coal; and when Watt's steam-engine became the great power in manufactures, such supply became absolutely essential to its existence as a manufacturing town." (8)

Canal Mania

The next venture was to connect this canal with "the Trent and the Potteries which needed heavy material, such as clay from Devon and Cornwall and flints from East Anglia, and whose products were at once too bulky and too fragile to be suitable for carriage by road." (9)

The financial success of the Bridgewater Canal encouraged other business people to join together to build canals. Josiah Wedgwood, from Burslem, in Staffordshire, had been transporting his pottery by pack-horses. The poor state of the roads meant a great number of breakages. In 1766 Wedgwood and some of his business friends decided to recruit James Brindley to build the Trent & Mersey Canal. (10)

The canal began within a few miles of the River Mersey, near Runcorn and finished in a junction with the River Trent in Derbyshire. It is just over ninety miles long with more than 70 locks and five tunnels. At the time it was described as the "greatest civil engineering work built in Britain." (11)

Although the canal cost £130,000 to build, it reduced the price of transporting Wedgwood's goods from £210s to 13s 4d a ton. The success of this canal resulted in Brindley being employed as the principal engineer on the Coventry Canal, the Oxford Canal, and the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal. (12)

James Brindley was now a "national hero, a model of how practical genius could triumph over low birth and near literacy". (13) Brindley was employed as the principal engineer on the Coventry Canal, the Oxford Canal, and the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal. Brindley was the principal engineer on over ten canals in all, including the Birmingham Canal, the Droitwich Canal, the Chesterfield Canal, and the Huddersfield Broad Canal. Several other canal companies, including the Leeds and Liverpool, employed Brindley as a consulting engineer for advice about a specific problem or to check the suggestions of other engineers. (14)

Joel Mokyr, the author of The Enlightened Economy: Britain and the Industrial Revolution (2009) has pointed out: "The most ambitious and costly project of the years of the Industrial Revolution was the construction of canals. In many respects, internal waterways were unglamorous projects. The technology involved was, in the main part, old and unspectacular. Canals were mostly designed for bulky, slow-moving cargoes and served mostly local transport needs, the average haul estimated at 26 miles or less. Much like turnpikes, they required parliamentary approval. They were also expensive to build and maintain, with a great deal of engineering ingenuity invested in the construction of aqueducts, embankments, bridges, locks, and tunnels." (15)

Canals were built by squads of mobile labourers, known as navvies. "Using just picks and shovels they dug trenches four feet deep and fifteen feet wide (to allow two boats to pass). Tunnels and occasional cuttings were made with the help of gunpowder, making canal work dangerous as well as physically hard. Every canal was lined with clay, which was then puddled into a hard non-porous layer by cattle or barefoot labourers." (16)

Canals and the Economy

Between 1790-1794 Parliament gave permission for the construction of canals. Until the building of the canals people were forced to produce and consume the great bulk of its own necessities. Now, the whole interior of England was now laid open to commerce: "The wheat, coal, pottery and iron goods of the Midlands found a ready way to the sea and coal in particular could now be carried easily to any part of the country". (17)

In his book, Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), the economist Adam Smith pointed out that the improvement in transport was stimulating the economy: "Good roads, canals, and navigable rivers, by diminishing the expense of carriage, put the remote parts of the country more nearly upon a level with those in the neighbourhood of the town. They are upon that account the greatest of all improvements. They encourage the cultivation of the remote, which must always be the most extensive circle of the country. They are advantageous to the town, by breaking down the monopoly of the country in its neighbourhood. They are advantageous even to that part of the country. Though they introduce some rival commodities into the old market, they open many new markets to its produce." (18)

Thomas Pennant, who toured Britain in 1779, agreed with Adam Smith and noted that the construction of canals had reduced the price of food and coal: "The fields, which before were barren, are now drained, and by the assistance of manure, conveyed on the canal toll-free, are clothed with a beautiful verdure. Places which rarely knew the use of coal are plentifully supplied with that essential article upon reasonable terms; and, what is of still greater public utility, the monopolizers of corn are prevented from exercising their infamous trade; for, communication being opened between Liverpool, Bristol, and Hull, and the line of canal being through countries abundant in grain, it affords a conveyance of corn unknown in past ages." (19)

In an attempt to increase profits canals were now built all over Britain. By 1838 there were 2,200 miles of canal and 1,800 miles of navigable river. These waterways linked almost every factory and industrial town in Britain. This system of waterways also provided a route to Britain's ports and the profitable overseas market. At the same time, goods imported from the rest of the world could be efficiently distributed throughout Britain. (20)

Primary Sources

(1) Samuel Smiles, James Brindley and the Early Engineers (1864)

The Duke of Bridgewater, more than any other single man, contributed to lay the foundations of the prosperity of Manchester and Liverpool. The cutting of the canal from Worsley to Manchester gave that town the immediate benefit of a cheap and abundant supply of coal; and when Watt's steam-engine became the great power in manufactures, such supply became absolutely essential to its existence as a manufacturing town....

It is at Worsley basin that the canal enters the bottom of the hill by a subterranean channel which extends to a great distance - connecting the different workings of the mine - so that the coals can be readily transported in boats to their place of sale ... In f3rindley's time this subterranean canal, hewn out of the rock, was only about a mile in length, but now extends to nearly forty miles underground in all directions. Where the tunnel passed through earth or coal, the arching was of brickwork; but where it passed through rock, it was simply hewn out. This tunnel acts not only as a drain and water-feeder for the canal itself, but as a means of carrying the facilities of the navigation through the very heart of the collieries; and it will readily be seen of how great a value it must have proved in the economical working of the navigation, as well as of the mines, as far as the traffic in coals was concerned.

(2) The Gloucester Journal newspaper (6 February, 1847)

On Tuesday last, John Savory, aged about 28, was drowned in the Comb Hill Canal. He was riding on a horse which was dragging a boat laden with hay, along the canal, when the horse slipped and fell into the water, and the young man was drowned.

(3) An advertisement for the Ashby de-la-Zouch Canal appeared in The Leicester Journal on 14th December, 1792. It compared the costs of transporting goods from Ashby Woulds to other places in the area.

Places Cost per ton by canal Cost per ton by road

Snarestone 3s 4d 9s 0d

Shacklestone 4s 7d 12s.0d

Dadlington 8s 4d 20s.0d

Burton Hastings 11s 3d 26s.0d

(4) William Albert, The Turnpike Road System: 1663-1840 (1972)

Canals excelled in the carriage of bulky low-value goods over long distances, while the roads were more important in the transport of passengers, the mails and goods for which speed or security of delivery was essential.

(5) Thomas Pennant, The Journey from Chester to London (1779)

The cottage, instead of being half covered with miserable thatch, is now covered with a substantial covering of tiles or slates, brought from the distant hills of Wales or Cumberland. The fields, which before were barren, are now drained, and by the assistance of manure, conveyed on the canal toll-free, are clothed with a beautiful verdure. Places which rarely knew the use of coal are plentifully supplied with that essential article upon reasonable terms; and, what is of still greater public utility, the monopolizers of corn are prevented from exercising their infamous trade; for, communication being opened between Liverpool, Bristol, and Hull, and the line of Canal being through countries abundant in grain, it affords a conveyance of corn unknown in past ages.

(6) Adam Smith, Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776)

Good roads, canals, and navigable rivers, by diminishing the expense of carriage, put the remote parts of the country more nearly upon a level with those in the neighbourhood of the town. They are upon that account the greatest of all improvements. They encourage the cultivation of the remote, which must always be the most extensive circle of the country. They are advantageous to the town, by breaking down the monopoly of the country in its neighbourhood. They are advantageous even to that part of the country. Though they introduce some rival commodities into the old market, they open many new markets to its produce.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) K. R. Fairclough, Francis Egerton, the Duke of Bridgewater : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(2) George M. Trevelyan, English Social History (1942) page 400

(3) Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007) page 42

(4) John Burke, History of England (1974) page 223

(5) Barrie Trinder, Britain's Industrial Revolution (2013) page 105

(6) Samuel Smiles, James Brindley and the Early Enginners (1864) page 225

(7) Joel Mokyr, The Enlightened Economy: Britain and the Industrial Revolution (2009) page 209

(8) Samuel Smiles, James Brindley and the Early Enginners (1864) page 239

(9) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938) page 285

(10) Jenny Uglow, The Lunar Men (2002) page 112

(11) Brian Dolan, Josiah Wedgwood: Entrepreneur to the Enlightenment (2004) page 316

(12) K. R. Fairclough, James Brindley : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(13) Jenny Uglow, The Lunar Men (2002) page 117

(14) K. R. Fairclough, James Brindley : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(15) Joel Mokyr, The Enlightened Economy: Britain and the Industrial Revolution (2009) page 209

(16) Roger Osborne, Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) page 269

(17) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938) page 286

(18) Adam Smith, Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) page 62

(19) Thomas Pennant, The Journey from Chester to London (1779) page 55

(20) Roger Osborne, Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) pages 266-273