The Peasant's Revolt and the end of Feudalism

Historians rarely use the term "revolution" when discussing political change in Britain. Some historians have argued that the English Civil War was a revolution as it resulted in the execution of King Charles I in 1649 and the introduction of a republican government led by Oliver Cromwell. It is pointed out that this was a revolution that only lasted just over ten years as King Charles II was restored in 1660. This is why the term Glorious Revolution is sometimes referred to when describing the constitutional monarchy that was established in 1688.

Tom Paine, who inspired both the American Revolution and the French Revolution, had little success in persuading people in his own country to change its political system. In the 20th century it was Karl Marx who was an important figure in the Russian Revolution and other communist overthrows of the established order.

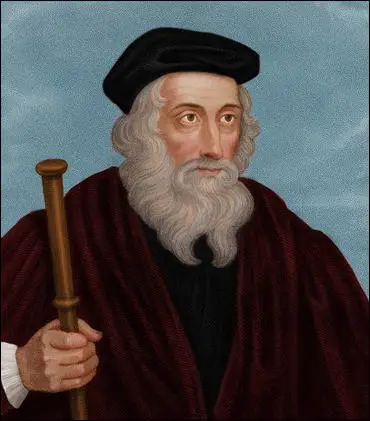

However, it could be argued that it was an Englishman who inspired a series of revolutions that began in the 14th century and did not finish until 200 years later. The man who was partly responsible for both the Peasants' Revolt and the English Reformation, was John Wycliffe, the curate of Ludgershall in Wiltshire. (1)

On 26th July 1374, Wycliffe was appointed as one of five new envoys to continue negotiations in Bruges with papal officials over clerical taxes and provisions. The negotiations ended without conclusion, and the representatives of each side retired for further consultation. (2) It has been argued that the failure of these negotiations had a profound impact on his religious beliefs. "He began to attack Rome's control of the English Church and his stance became increasingly anti-Papal resulting in condemnation of his teachings and threats of excommunication." (3)

John Wycliffe antagonized the orthodox Church by disputing transubstantiation, the doctrine that the bread and wine become the actual body and blood of Christ. Wycliffe developed a strong following and those who shared his beliefs became known as Lollards. They got their name from the word "lollen", which signifies to sing with a low voice. The term was applied to heretics because they were said to communicate their views in a low muttering voice. (4)

In a petition later presented to Parliament, the Lollards claimed: "That the English priesthood derived from Rome, and pretending to a power superior to angels, is not that priesthood which Christ settled upon his apostles. That the enjoining of celibacy upon the clergy was the occasion of scandalous irregularities. That the pretended miracle of transubstantiation runs the greatest part of Christendom upon idolatry. That exorcism and benedictions pronounced over wine, bread, water, oil, wax, and incense, over the stones for the altar and the church walls, over the holy vestments, the mitre, the cross, and the pilgrim's staff, have more of necromancy than religion in them.... That pilgrimages, prayers, and offerings made to images and crosses have nothing of charity in them and are near akin to idolatry." (5)

As one of the historians of this period of history, John Foxe, has pointed out: "Wycliffe, seeing Christ's gospel defiled by the errors and inventions of these bishops and monks, decided to do whatever he could to remedy the situation and teach people the truth. He took great pains to publicly declare that his only intention was to relieve the church of its idolatry, especially that concerning the sacrament of communion. This, of course, aroused the anger of the country's monks and friars, whose orders had grown wealthy through the sale of their ceremonies and from being paid for doing their duties. Soon their priests and bishops took up the outcry." (6)

John Wycliffe and the English Bible

It is believed that John Wycliffe and his followers began translating the Bible into English. Henry Knighton, the canon of St Mary's Abbey, Leicester, reported disapprovingly: "Christ delivered his gospel to the clergy and doctors of the church, that they might administer it to the laity and to weaker persons, according to the states of the times and the wants of men. But this Master John Wycliffe translated it out of Latin into English, and thus laid it out more open to the laity, and to women, who could read, than it had formerly been to the most learned of the clergy, even to those of them who had the best understanding. In this way the gospel-pearl is cast abroad, and trodden under foot of swine, and that which was before precious both to clergy and laity, is rendered, as it were, the common jest of both. The jewel of the church is turned into the sport of the people, and what had hitherto been the choice gift of the clergy and of divines, is made for ever common to the laity." (7)

In September 1376, Wycliffe was summoned from Oxford by John of Gaunt to appear before the king's council. He was warned about his behaviour. Thomas Walsingham, a Benedictine monk at St Albans Abbey, reported that on 19th February, 1377, Wycliffe was told to appear before Archbishop Simon Sudbury and charged with seditious preaching. Anne Hudson has argued: "Wycliffe's teaching at this point seems to have offended on three matters: that the pope's excommunication was invalid, and that any priest, if he had power, could pronounce release as well as the pope; that kings and lords cannot grant anything perpetually to the church, since the lay powers can deprive erring clerics of their temporalities; that temporal lords in need could legitimately remove the wealth of possessioners." On 22nd May 1377, Pope Gregory XI issued five bulls condemning the views of John Wycliffe. (8)

John Wycliffe tried to employ the Christian vision of justice to achieve social change: "It was through the teachings of Christ that men sought to change society, very often against the official priests and bishops in their wealth and pride, and the coercive powers of the Church itself." (9) Barbara Tuchman has claimed that John Wycliffe was the first "modern man". She goes on to argue: "Seen through the telescope of history, he (Wycliffe) was the most significant Englishman of his time." (10)

The Poll Tax

King Edward III had problems fighting what became known as the Hundred Years War. He achieved early victories at Crécy and Poitiers, but by 1370 the French won a succession of battles and were able to raid and loot towns on the south coast. Fighting the war was very expensive and in February 1377 the government introduced a poll-tax where four pence was to be taken from every man and woman over the age of fourteen. "This was a huge shock: taxation had never before been universal, and four pence was the equivalent of three days' labour to simple farmhands at the rates set in the Statute of Labourers". (11)

King Edward died soon afterwards. His ten-year-old grandson, Richard II, was crowned in July 1377. John of Gaunt, Richard's uncle, took over much of the responsibility of government. He was closely associated with the new poll-tax and this made him very unpopular with the people. They were very angry as they considered the tax unfair as the poor had to pay the same tax as the wealthy. Despite this, the collectors of the tax seem not to have had to face more than an occasional, local disturbance. (12)

In 1379 Richard II called a parliament to raise money to pay for the continuing war against the French. After much debate it was decided to impose another poll tax. This time it was to be a graduated tax, which meant that the richer you were, the more tax you paid. For example, the Duke of Lancaster and the Archbishop of Canterbury had to pay £6.13s.4d., the Bishop of London, 80 shillings, wealthy merchants, 20 shillings, but peasants were only charged 4d.

The proceeds of this tax was quickly spent on the war or absorbed by corruption. In 1380, Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury, suggested a new poll tax of three groats (one shilling) per head over the age of fifteen. "There was a maximum payment of twenty shillings from men whose families and households numbered more than twenty, thus ensuring that the rich paid less than the poor. A shilling was a considerable sum for a working man, almost a week's wages. A family might include old persons past work and other dependents, and the head of the family became liable for one shilling on each of their 'polls'. This was basically a tax on the labouring classes." (13)

The peasants felt it was unfair that they should pay the same as the rich. They also did not feel that the tax was offering them any benefits. For example, the English government seemed to be unable to protect people living on the south coast from French raiders. Most peasants at this time only had an income of about one groat per week. This was especially a problem for large families. For many, the only way they could pay the tax was by selling their possessions. John Wycliffe gave a sermon where he argued: "Lords do wrong to poor men by unreasonable taxes... and they perish from hunger and thirst and cold, and their children also. And in this manner the lords eat and drink poor men's flesh and blood." (14)

John Ball toured Kent giving sermons attacking the poll tax. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, heard about this he gave orders that Ball should not be allowed to preach in church. Ball responded by giving talks on village greens. The Archbishop now gave instructions that all people found listening to Ball's sermons should be punished. When this failed to work, Ball was arrested and in April 1381 he was sent to Maidstone Prison. (15) At his trial it was claimed that Ball told the court he would be "released by twenty thousand armed men". (16)

The Peasants' Revolt in 1381

In May 1381, Thomas Bampton, the Tax Commissioner for the Essex area, reported to the king that the people of Fobbing were refusing to pay their poll tax. It was decided to send a Chief Justice and a few soldiers to the village. It was thought that if a few of the ringleaders were executed the rest of the village would be frightened into paying the tax. However, when Chief Justice Sir Robert Belknap arrived, he was attacked by the villagers. (17)

Belknap was forced to sign a document promising not to take any further part in the collection of the poll tax. According to the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's: "The Commons rose against him and came before him to tell him... he was maliciously proposing to undo them... Accordingly they made him swear on the Bible that never again would he hold such sessions nor act as Justice in such inquests... And Sir Robert travelled home as quickly as possible." (18)

After releasing the Chief Justice, some of the villagers looted and set fire to the home of John Sewale, the Sheriff of Essex. Tax collectors were executed and their heads were put on poles and paraded around the neighbouring villages. The people responsible sent out messages to the villages of Essex and Kent asking for their support in the fight against the poll tax. (19)

Many peasants decided that it was time to support the ideas proposed by John Ball and his followers. It was not long before Wat Tyler, a former soldier in the Hundred Years War, emerged as the leader of the peasants. Tyler's first decision was to march to Maidstone to free John Ball from prison. "John Ball had been set free and was safe among the commons of Kent, and he was bursting to pour out the passionate words which had been bottled up for three months, words which were exactly what his audience wanted to hear." (20)

Charles Poulsen, the author of The English Rebels (1984) has pointed out that it was very important for the peasants to be led by a religious figure: "For some twenty years he had wandered the country as a kind of Christian agitator, denouncing the rich and their exploitation of the poor, calling for social justice and freeman and a society based on fraternity and the equality of all people." John Ball was needed as their leader because alone of the rebels, he had access to the word of God. "John Ball quickly assumed his place as the theoretician of the rising and its spiritual father. Whatever the masses thought of the temporal Church, they all considered themselves to be good Catholics." (21)

On 5th June there was a revolt at Dartford and two days later Rochester Castle was taken. The peasants arrived in Canterbury on 10th June. Here they took over the archbishop's palace, destroyed legal documents and released prisoners from the town's prison. More and more peasants decided to take action. Manor houses were broken into and documents were destroyed. These records included the villeins' names, the rent they paid and the services they carried out. What had originally started as a protest against the poll tax now became an attempt to destroy the feudal system. (22)

The peasants decided to go to London to see Richard II. As the king was only fourteen-years-old, they blamed his advisers for the poll tax. The peasants hoped that once the king knew about their problems, he would do something to solve them. The rebels reached the outskirts of the city on 12 June. It has been estimated that approximately 30,000 peasants had marched to London. At Blackheath, John Ball gave one of his famous sermons on the need for "freedom and equality". (23)

Wat Tyler also spoke to the rebels. He told them: "Remember, we come not as thieves and robbers. We come seeking social justice." Henry Knighton records: "The rebels returned to the New Temple which belonged to the prior of Clerkenwell... and tore up with their axes all the church books, charters and records discovered in the chests and burnt them... One of the criminals chose a fine piece of silver and hid it in his lap; when his fellows saw him carrying it, they threw him, together with his prize, into the fire, saying they were lovers of truth and justice, not robbers and thieves." (24)

Charles Poulsen praises Wat Tyler as learning the "lessons of organisation and discipline" when in the army and in showing the "same pride in the customs and manners of his own class as the noblest baron would for his". (25) The medieval historians were less complimentary and Thomas Walsingham described him as a "cunning man, endowed with much sense if he had applied his intelligence to good purposes". (26)

Richard II gave orders for the peasants to be locked out of London. However, some Londoners who sympathised with the peasants arranged for the city gates to be left open. Jean Froissart claims that some 40,000 to 50,000 citizens, about half of the city's inhabitants, were ready to welcome the "True Commons". (27) When the rebels entered the city, the king and his advisers withdrew to the Tower of London. Many poor people living in London decided to join the rebellion. Together they began to destroy the property of the king's senior officials. They also freed the inmates of Marshalsea Prison. (28)

Part of the English Army was at sea bound for Portugal whereas the rest were with John of Gaunt in Scotland. (29) Thomas Walsingham tells us that the king was being protected in the Tower by "six hundred warlike men instructed in arms, brave men, and most experienced, and six hundred archers". Walsingham adds that they "all had so lost heart that you would have thought them more like dead men than living; the memory of their former vigour and glory was extinguished". Walsingham points out that they did not want to fight and suggests they may have been on the side of the peasants. (30)

John Ball sent a message to Richard II stating that the rising was not against his authority as the people only wished only to deliver him and his kingdom from traitors. Ball also asked the king to meet with him at Blackheath. Archbishop Simon Sudbury and Robert Hales, the treasurer, both objects of the people's hatred, warned against meeting the "shoeless ruffians", whereas others, such as William de Montagu, the Earl of Salisbury, urged that the king played for time by pretending that he desired a negotiated agreement. (31)

Richard II agreed to meet the rebels outside the town walls at Mile End on 14th June, 1381. Most of his soldiers remained behind. Charles Oman, the author of The Great Revolt of 1381 (1906), pointed the "ride to Mile End was perilous: at any moment the crowd might have broken loose, and the King and all his party might have perished... nevertheless, though surrounded all the way by a noisy and boisterous multitude, Richard and his party ultimately reached Mile End". (32)

John Ball at Mile End from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

When the king met the rebels at 8.00 a.m. he asked them what they wanted. Wat Tyler explained the demands of the rebels. This includes the end of all feudal services, the freedom to buy and sell all goods, and a free pardon for all offences committed during the rebellion. Tyler also asked for a rent limit of 4d per acre and an end to feudal fines through the manor courts. Finally, he asked that no "man should be compelled to work except by employment under a regularly reviewed contract". (33)

The king immediately granted these demands. Wat Tyler also claimed that the king's officers in charge of the poll tax were guilty of corruption and should be executed. The king replied that all people found guilty of corruption would be punished by law. The king agreed to these proposals and 30 clerks were instructed to write out charters giving peasants their freedom. After receiving their charters the vast majority of peasants went home.

G. R. Kesteven, the author of The Peasants' Revolt (1965), has pointed out that the king and his officials had no intention of carrying out the promises made at this meeting, they "were merely using those promises to disperse the rebels". (34) However, Wat Tyler and John Ball were not convinced by the word given by the king and along with 30,000 of the rebels stayed in London. (35)

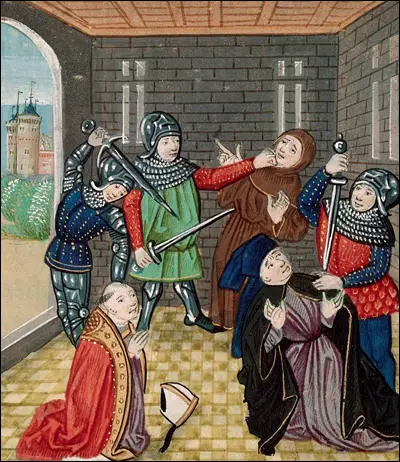

While the king was in Mile End discussing an agreement with the king, another group of peasants marched to the Tower of London. There were about 600 soldiers defending the Tower but they decided not to fight the rebel army. Simon Sudbury (Archbishop of Canterbury), Robert Hales (King's Treasurer) and John Legge (Tax Commissioner), were taken from the Tower and executed. Their heads were then placed on poles and paraded through the streets of cheering Londoners. (36)

The killing of Archbishop Simon Sudbury and Robert Hales

from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

Rodney Hilton argues that the rebels wanted revenge on all those involved in the levying of taxes or the administrating the legal system. Roger Leggett, one of the most important government lawyers was also killed. "They attacked not only the lawyers themselves - attorneys, pleaders, clerks of the courts - but others closely associated with the judicial processes... The hostility to lawyers and to legal records was not of course peculiar to the Londoners. The widespread destruction of manorial court records is well-known" during the rebellion. (37)

The rebels also attacked foreign workers living in London. "The commons made proclamation that every one who could lay hands on Flemings or any other strangers of other nations might cut off their heads". (38) It has been claimed that "some 150 or 160 unhappy foreigners were murdered in various places - thirty-five Flemings in one batch were dragged out of the church of St. Martin in the Vintry, and beheaded on the same block... The Lombards also suffered, and their houses yielded much valuable plunder." (39)

Death of Wat Tyler and John Ball

It was agreed that another meeting should take place between Richard II and the leaders of the rebels at Smithfield on 15th June, 1381. William Walworth rode "over to the rebels and summoned Wat Tyler to meet the king, and mounted on a little pony, accompanied by only one attendant bearing the rebel banner, he obeyed". When he joined the king he put forward another list of demands that included: the removal of the lordship system, the distribution of the wealth of the church to the poor, a reduction in the number of bishops, and a guarantee that in future there would be no more villeins. (40)

Richard II said he would do what he could. Wat Tyler was not satisfied by this reply. He called for a drink of water to rinse out his mouth. This was seen as extremely rude behaviour, especially as Tyler had not removed his hood when talking to the king. One of Richard's party shouted out that Tyler was "the greatest thief and robber in Kent". The author of the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's claims: "For these words Wat wanted to strike the valet with his dagger, and would have killed him in the king's presence; but because he tried to do so, the Mayor of London, William of Walworth... arrested him... Wat stabbed the mayor with his dagger in the body in great anger. But, as it pleased God, the mayor was wearing armour and took no harm.. he struck back at the said Wat, giving him a deep cut in the neck, and then a great blow on the head. And during the scuffle a valet of the king's household drew his sword, and ran Wat two or three times through the body... Wat was carried by a group of the commons to the hospital for the poor near St Bartholomew's, and put to bed. The mayor went there and found him, and had him carried out to the middle of Smithfield, in the presence of his companions, and had him beheaded." (41)

The death of Wat Tyler from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

The peasants raised their weapons and for a moment it looked as though there was going to be fighting between the king's soldiers and the peasants. However, Richard rode over to them and said: "Will you shoot your king? I will be your chief and captain, you shall have from me that which you seek " He then spoke to them for some time and eventually they agreed to go back to their villages and the Peasants' Revolt was over. (42)

An army, led by Thomas of Woodstock, John of Gaunt's younger brother, was sent into Essex to crush the rebels. A battle between the peasants and the King's army took place near the village of Billericay on 28th June. The king's army was experienced and well-armed and the peasants were easily defeated. It is believed that over 500 peasants were killed during the battle. The remaining rebels fled to Colchester, where they tried in vain to persuade the towns-people to support them. They then fled to Huntingdon but the towns people there chased them off to Ramsey Abbey where twenty-five were slain. (43)

King Richard with a large army began visiting the villages that had taken part in the rebellion. At each village, the people were told that no harm would come to them if they named the people in the village who had encouraged them to join the rebellion. Those people named as ringleaders were then executed. Apparently the king stated: "Serfs you are and serfs you will remain." A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has pointed out: "The promises made by the king were repudiated and the common people of England learnt, not for the last time, how unwise it was to trust to the good faith of their rulers." (44)

The king's officials were instructed to look out for John Ball. He was eventually caught in Coventry. He was taken to St Albans to stand trial. "He denied nothing, he freely admitted all the charges without regrets or apologies. He was proud to stand before them and testify to his revolutionary faith." He was sentenced to death, but William Courtenay, the Bishop of London, granted a two-day stay of execution in the hope that he could persuade Ball to repent of his treason and so save his soul. John Ball refused and he was hanged, drawn and quartered on 15th July, 1381. (45)

Decline of Feudalism

In 1382 John Wycliffe was condemned as a heretic and was forced into retirement. (46) Archbishop William Courtenay urged Parliament to pass a Statute of the Realm against preachers such as Wycliffe: "It is openly known that there are many evil persons within the realm, going from county to county, and from town to town, in certain habits, under dissimulation of great holiness, and without the licence ... or other sufficient authority, preaching daily not only in churches and churchyards, but also in markets, fairs, and other open places, where a great congregation of people is, many sermons, containing heresies and notorious errors." (47) Wycliffe died on 31st December, 1384. (48)

Although initially it failed to achieve its aim, the Peasants' Revolt was an important event in English history. For the first time, peasants had joined together in order to achieve political change. The king and his advisers could no longer afford to ignore their feelings. In 1382 a new poll tax was voted in by Parliament. This time it was decided that only the richer members of society should pay the tax. (49)

After the Peasants Revolt the lords found it very difficult to retain the feudal system. Villeinage was already crumbling due to economic and demographic pressures. (50) Labour was still in short supply and villeins continued to run away to find work as freemen. In 1390 the government attempt to keep wages at the old level was abandoned when a new Statute of Labourers Act gave the Justices of the Peace the power to fix wages for their districts in accordance with the prevailing prices. (51)

Even the villeins who stayed were much more reluctant to work on the lord's demesne. In some villages the villeins joined together and refused to carry out any more labour services. Several towns and villages saw outbreaks of violence. However, as Charles Oman has pointed out, these were "scattered and sporadic, instead of simultaneous". (52)

Unable to find enough labour to work their demesne, lords found it more profitable to lease out the land. With smaller areas to farm, the lords had less need for the labour services provided by the villeins. Lords started to "commute" these labour services. This meant that in return for a cash payment, peasants no longer had to work on the lord's demesne. During this period wages increased significantly. (53)

Charles Poulsen, the author of The English Rebels (1984) argues that in the long-term the peasants did win: "The concept of freedom was not killed in the repression. It was nurtured and grew until it became the cornerstone of the national political structure, changing as life and circumstances changed." (54) These rebellions spread throughout Europe and similar uprisings took place in Germany, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Finland and Switzerland. (55)

The decline in the feudal system continued for the next 200 years, and by the time of Henry VIII it "had for all intents and purposes ceased to play any great part in the rural economy". However, as late as 1574 Queen Elizabeth "found some stray villeins on royal demesne to emancipate." (56)