William the Conqueror and the Feudal System

After the Battle of Hastings the Normans, led by William the Conqueror and his army now marched on Dover where he remained for a week. He then went north calling in on Canterbury before arriving on the outskirts of London. He met resistance in Southwark and in an act of revenge set fire to the area. Londoners refused to submit to William so he turned away and marched through Surrey, Hampshire and Berkshire. He ravaged the countryside and by the end of the year the people of London, surrounded by devastated lands, began to consider the possibility of surrender. (1)

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a group of senior figures, including Earl Edwin of Mercia, Earl Morcar of Northumbria, Edgar Etheling, Ealdred, Archbishop of York and "all the best men from London, who submitted from force of circumstances... They gave him hostages and swore oaths of fealty, and he promised to be a gracious lord to them." On 25th December, 1066, William was crowned king of England at Westminster Abbey. (2)

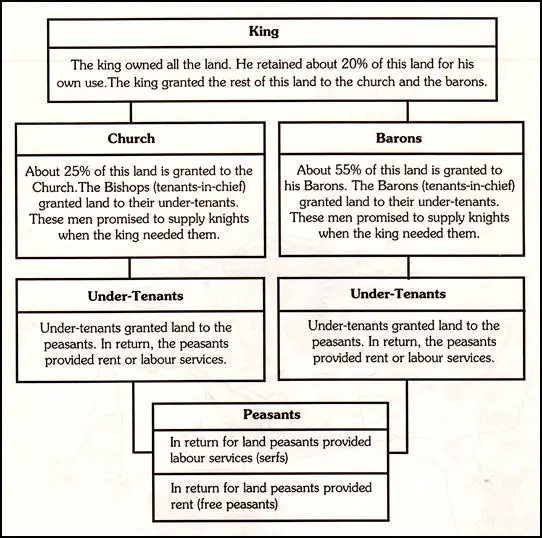

After his coronation, William the Conqueror claimed that all the land in England now belonged to him. William retained about a fifth of this land for his own use. Another 25% went to the Church. The rest were given to 170 tenants-in-chief (or barons), who had helped him defeat Harold at the Battle of Hastings. These barons had to provide armed men on horseback for military service. The number of knights a baron had to provide depended on the amount of land he had been given.

When William granted land to a baron an important ceremony took place. The baron knelt before the king and said: "I become your man." He then placed his hand on the Bible and promised to remain faithful for the rest of his life. The baron would then carry out similar ceremonies with his knights. By the time William and his barons had finished distributing land there were about 6,000 manors in England. Manors varied in size, some having only one village, while others had several villages within its territory.

Richard FitzGilbert is an example of someone who did very well out of the Norman invasion. Richard had the same mother as William the Conqueror, Herleva of Falaise. His father, Gilbert, Count of Brionne, one of the most powerful landowners in Normandy. As Herleva was not married to Gilbert, the boy became known as Richard FitzGilbert. The term 'Fitz' was used to show that Richard was the illegitimate son of Gilbert. (3)

When Robert, Duke of Normandy, William's father died in 1035, William the Conqueror, inherited his father's title. Several leading Normans, including Gilbert of Brionne, Osbern the Seneschal and Alan of Brittany, became William's guardians. A number of Norman barons would not accept an illegitimate son as their leader and in 1040 an attempt was made to kill William. The plot failed but they did manage to kill Gilbert of Brionne. As Richard was illegitimate, he did not receive very much land when his father died. (4)

When William the Conqueror, decided to invade England in 1066, he invited his three half-brothers, Richard FitzGilbert, Odo of Bayeux and Robert of Mortain to join him. Richard, who had married Rohese, daughter of Walter Giffard of Normandy, also brought with him members of his wife's family.

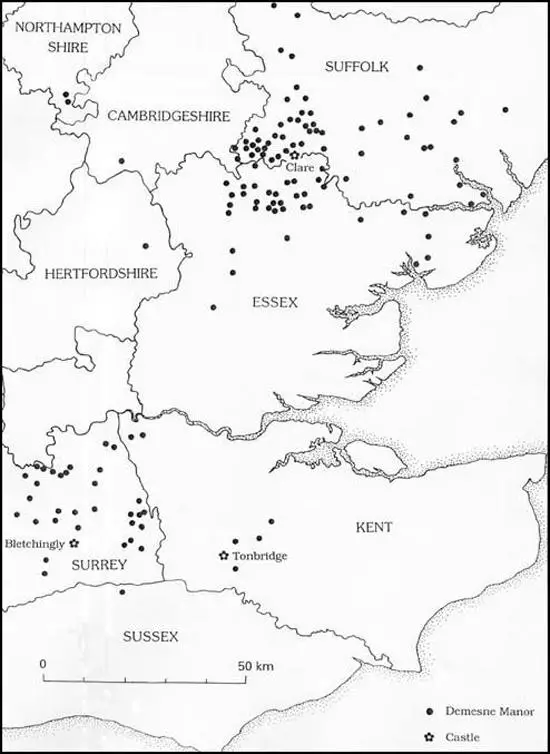

Richard FitzGilbert, was granted land in Kent, Essex, Surrey, Suffolk and Norfolk. In exchange for this land. Richard had to promise to provide the king with sixty knights. In order to supply these knights, barons divided their land up into smaller units called manors. These manors were then passed on to men who promised to serve as knights when the king needed them. (5)

Richard FitzGilbert was given the title, the Earl of Clare. The baron often lived in a castle at the centre of his estates. FitzGilbert built castles at Tonbridge (Kent), Clare (Suffolk), Bletchingley (Surrey) and Hanley (Worcester). His knights normally lived in the manor that they had been granted. Once or twice a year, FitzGilbert would visit his knights to check the manor accounts and to collect the profits that the land had made. (6)

Barons often kept about a third of the land in the manor for their own use (the demesne). Another large area was given to the knight who looked after the manor. The rest was divided up between the church (the glebe land) and the peasants who lived in the village. Those peasants who were freeman would rent the land for an agreed fee. However, the vast majority of the peasants were unfree. These unfree peasants, who were called villeins or serfs, had to provide a whole range of services in exchange for the land that they used. The main requirement of the serf was to supply labour service. This involved working on the demesne without pay for several days a week. As well as free labour, serfs also had to provide the oxen plough-team or any equipment that was needed.

Defending his Empire

In 1067 William and his army went on a tour of England where he organised the confiscating of lands, built castles and established law and order. His chroniclers claim that he met no opposition during his travels around the country. After appointing his half-brother Odo of Bayeux, and William FitzOsbern, as co-regents, William went to Normandy in March 1067.

While he was away, disturbances broke out in Kent, Herefordshire, and in the north of the country. William returned to England in December, 1067, and over the next few months the rebellions were put down. However, in 1068, another insurrection, led by Harold's sons, took place at Exeter. Once again he successfully defeated the rebels. Afterwards he built castles in Exeter and other key towns. This included Durham which was the scene of a rebellion in 1069. (7)

William also had to deal with raids on the north led by King Sweyn of Denmark. In September 1069, Sweyn's fleet sailed into the Humber and burnt York. William's army forced the Danes to retreat and then crushed another uprising in Staffordshire. He then burnt crops, house and property of people living between York and Durham. The chroniclers claim that the area was turned into a desert and people died of starvation. The revolt finally came to an end when William's troops captured Chester in 1070. A. L. Morton argues that "the greater part of Yorkshire and Durham was laid waste and remained almost unpeopled for a generation". (8)

In 1071 another revolt broke out. Led by Hereward the rebels captured the Isle of Ely. He held out in the fen country for more than a year. During this period Earl Edwin of Mercia and Earl Morcar of Northumbria, were killed. William personally led the Norman army against Hereward. He managed to escape but William punished the rebels he caught with mutilation and lifelong imprisonment and built a new castle at Ely. (9)

William returned to Normandy in 1073 and later that year conquered Maine. While he was away Waltheof, the Earl of Northumbria, began to conspire against him. Geoffrey of Coutances led the fight against the uprising and afterwards ordered that all rebels should have their right foot cut off. Waltheof was arrested: "His motives, even his actions, were uncertain at the time and have been contentious ever since. Waltheof certainly did not rebel openly. It may have been simply (as one later version had it) that he knew about a conspiracy against the king and was slow in reporting it, or (following another account) that he went along with the plot when it was first put to him, only to have immediate reservations and throw himself on the king's mercy." William had him executed - the only time capital punishment was inflicted on an English leader during his reign. (10)

In 1077 William's eldest son, Robert Curthose, suggested that he should become the ruler of Normandy and Maine. When the king refused, Robert rebelled and attempted to seize Rouen. The rebellion failed and Robert was forced to flee and established himself at Gerberoi. William besieged him there in 1080 but his wife, Matilda of Flanders, managed to persuade the two men to end their feud. (11)

Odo of Bayeux had been left in control of England while William was in Normandy. In 1082 William heard complaints about Odo's behaviour. He returned to England and Odo was arrested and charged with misgovernment and oppression. It was also claimed that Odo was preparing an expedition to Rome to become pope after Gregory VII. Found guilty he was kept in prison for the next five years. (12)

The Domesday Book

In 1085 William returned to England to deal with a suspected invasion by King Canute IV of Denmark. While waiting for the attack to take place he decided to order a comprehensive survey of his kingdom. There were three main reasons why William decided to order a survey. (1) The information would help William discover how much the people of England could afford to pay in tax. (2) The information about the distribution of the population would help William plan the defence of England against possible invaders. (3) There was a great deal of doubt about who owned some of the land in England. William planned to use this information to help him make the right judgements when people were in dispute over land ownership. (13)

William sent out his officials to every town, village and hamlet in England. They asked questions about the ownership of land, animals and farm equipment and also about the value of the land and how it was used. When the information was collected it was sent to Winchester where it was recorded in a book. About a hundred years after it was produced the book became known as the Domesday Book. Domesday means "day of judgement".

William's survey was completed in only seven months. When William knew who the main landowners were, he arranged a meeting for them at Salisbury. At this meeting on 1st August, 1086, he made them all swear a new oath that they would always obey their king. John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984) points out that "from this unique document we have an unparalleled picture of early medieval society in England, including much about the peasantry." (14)

In later life William became very fat. In 1087 William was told that King Philip of France described him as looking like a pregnant woman. William was furious and on mounted an attack on the king's territory. On 15th August he captured Mantes and set fire to the town. Soon afterwards he fell from his horse and suffered internal injuries. Ordericus Vitalis said that as he was "very corpulent" he "fell sick from the excessive heat and his great fatigues". (15)

William was taken to the priory of St. Gervase. Close to death, he directed that Robert Curthose should succeed him in Normandy and William Rufus should become king of England. William said on his deathbed that "I tremble when I reflect on the grievous sins which burden my conscience, and now, about to be summoned before the awful tribunal of God, I know not what I ought to do. I was too fond of war... I was bred to arms from my childhood, and I am stained with the rivers of blood that I have shed." (16)