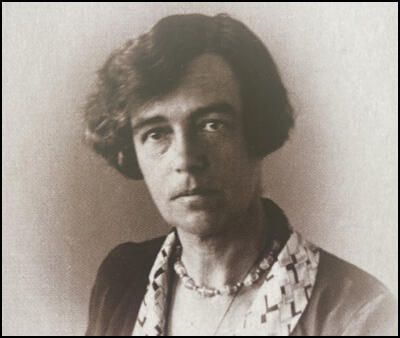

Theodora Bosanquet

Theodora Bosanquet, the daughter of Frederick Charles Tindal Bosanquet (1847–1928), curate of Yaverland, and his first wife, Gertrude Mary Fox Bosanquet (1854–1900) was born at Enfield Cottage, Sandown, Isle of Wight, on 3rd October 1880. Her mother was the second cousin of Charles Darwin and the biblical historian James Whatman Bosanquet was her paternal grandfather. (1)

Theodora attended Cheltenham Ladies' College before gaining a B.Sc. at University College, where she studied biology, geology and some physics. (2) In 1907 she began working for Mary Petherbridge's Secretarial Bureau. The following year she discovered that Henry James, one of her favourite authors, needed a "literary secretary". She applied for the post and by October 1908, she was living in Marigold Cottage in Rye and took daily dictation from him at his home Lamb House. (3)

Theodora was thrilled that she had a job she loved and recorded the excitement of receiving her first week's wage, "the first money I'd ever earned". (4) Henry James introduced her to literary figures such as Rose Macaulay, Naomi Royde-Smith, and Clara Smith. They encouraged her to write and had essays, fiction, poems, and reviews published over the next few years. (5)

Henry James moved to London and Theodora took rooms in Chelsea's Cheyne Walk. His health was deteriorating and he was forced to dictate from his bedroom during his last months before his death in February 1916. The novelist, Edith Wharton offered her a secretarial post based in Paris but she declined. At that time Britain was involved in the First World War and decided to work in the War Trade Intelligence Department. On leaving this job she became executive secretary to the International Federation of University Women. (6)

Theodora Bosanquet and Time and Tide

It was in this post she met Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda. In 1927 she began reviewing regularly for Time and Tide. Extracts of her study of Harriet Martineau appeared in the magazine. She described Martineau's success as "an astonishing triumph of natural capacity over the disabilities of her position, her health and her sex." (7)

At this time Lady Rhondda was living with Helen Archdale at Stonepitts Manor House. (8) The house had seven bedrooms. The gardens were enclosed within high, red-brick walls and included a tennis court, rose gardens, rock gardens and a kitchen garden. The two women often had literary figures staying for the weekend: "Everyone wrote, read and talked as they liked. The result was some marvellous conversation and really gracious living." (9)

Lady Rhondda and Helen Archdale often had political disagreements and increasing editorial interventions, resulted in her being effectively forced out of the editorship of Time and Tide. Although she remained a director of Time and Tide Publishing Company, "after her resignation specifically feminist concerns were gradually marginalized in" the magazine. (10)

Although the two women continued to live together the relationship was in difficulty. In a letter written in November, 1926, Margaret commented: "I don't know whether you ever ask yourself why we live together; if you ever go back to the time when we first came together. We began it for the only reason that can make living together possible, because we were very fond of one another. I have paid heavily for believing that your love, that seemed a real thing, was real - when in fact it can only have been a passing surface passion, much as I've seen you several times. I gave all I had to give and for years now I have been struggling not to see, what you were making only abundantly clear, that the only value I had in your eyes was as some one who could give the children treats." (11)

The two women continued to live together but Lady Rhondda resented the fact that she was paying all the bills: "I very much dislike spending a lot of money when I am already living beyond my income as I am these bad years". (12) They still spent times together at Stonepitts Manor House but as Helen explained to a friend "we do not necessarily go together in fact it is rarely that we coincide." It was not until the spring of 1931 that Helen left the house for good. (13)

Lady Rhondda

In the Easter 1933 Theodora and Lady Rhondda went on a cruise to Madeira, Tenerife, Morocco and Gibraltar. Before the cruise Theodora had admitted to herself that she was attracted by the young Theresa J. Dillon. However, she noted that "at my time of life sexual adventures are not likely to be much in my way" and reasoned that "the Platonic ideal of controlled impulse is probably the ideal for friendship". (14)

The following autumn they went on another cruise. They became intimate and on their return, to live together in Rhondda's Hampstead flat. (15) Four years later they moved into the newly built Churt Halewell near Shere in Surrey. When she first saw the house Bosanquet described the house as "A delight. A pleasance. It will give unmixed satisfaction." Built of local sandstone with "a lovely garden and hidden walkways, it was surrounded by woods and offered privacy, comfort and space." Lady Rhondda also added a swimming pool. (16)

In 1937 Theodora Bosanquet became literary editor of Time and Tide. It was argued by C. V. Wedgwood that "Many writers who were young in the thirties and forties have happy memories of her kindly welcome in the generously untidy, yet methodical, book room of Time and Tide, and many owe their introduction into the world of literary journalism to one of the little luncheon parties she used to give at the now vanished Gourmets Restaurant". (17)

Lady Rhondda told Winifred Holtby that Bosanquet "is very fine I think in many ways - finer than she gets the credit for being." (18) Freya Stark commented that Bosanquet was both "fastidious and amusing" and that Lady Rhondda and her "go very well together". (19)

Society of Psychical Research

Bosanquet was interested in the scientific investigation of paranormal phenomena; she was a longstanding member of the Society of Psychical Research (SPR), and edited its journal during the Second World War, and served on its council from 1945. "Bosanquet's papers in the SPR archive, including notes, clairaudient talks, and meditations, show that she regularly practised automatic writing through the 1930s and 1940s, sometimes several times a day." (20)

Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda, became ill with cancer she refused medication on the grounds that Time and Tide demanded a clear mind. She died in the Westminster Hospital on 20th July 1958. (21) Bosanquet now moved to a single room at Crosby Hall. She died on 1st June 1961 at St Mary Abbot's Hospital, Kensington, London. After a funeral at Chelsea Old Church, Cheyne Walk, she was cremated. (22)

Primary Sources

(1) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013)

Theodora had been born on 3 October 1880 at Sandown on the Isle of Wight where her father was a curate. She spent part of her childhood in Dorset and Devon. Her mother Gertrude died in her mid-forties in 1900 and her father Frederick C. T. Bosanquet remarried... Other relatives included the philosopher Bernard Bosanquet and his brother Charles, who founded the Charity Organisation Society. On her mother's side were even more illustrious connections: her maternal grandfather was Charles Darwin's second cousin.

(2) Catherine Clay, Theodora Bosanquet: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (8th September 2022)

She was educated at Cheltenham Ladies' College, from where she passed the London University matriculation in 1903, and University College, London. She went on to graduate BSc in geology from the University of London in 1906.Bosanquet left the family home in her twenties, preferring professional work and independence to the leisured lives of her parents and many other women of her class and generation. She began training as an indexer under Mary Petherbridge who ran a secretarial bureau off Conduit Street, London. In the summer of 1907 Bosanquet heard that the American novelist Henry James was looking for a new secretary. Promptly learning how to use a Remington typewriter, she traded the art and craft of indexing to work for "the Master" in the role of typist, starting the job in October 1907 at James's home, Lamb House, in Rye, Sussex. James was delighted with his new secretary, and she remained in his employ in Rye, and later (following a year's interlude from 1910 to 1911 when James was in America) in Chelsea, London, until his death in February 1916.

Bosanquet wrote three well-received books during her tenure at the IFUW: Henry James at Work (1924), Harriet Martineau: An Essay in Comprehension (1927), and Paul Valéry (1933). The first of these, based on her experience of working for James during the last years of his life, is the best-known of her works. Published by the Hogarth Press, it placed Bosanquet at the forefront of Jamesian scholarship... As a study of the nineteenth century's leading ‘woman of letters', Harriet Martineau is evidence of Bosanquet's feminist commitments, while Paul Valéry interested her not only as a notoriously difficult French symbolist poet, but also because of his membership of the Arts and Letters Committee of the League of Nations' Paris-based International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation.

(3) C. V. Wedgwood, The Times (3rd June 1961)

Many writers who were young in the thirties and forties have happy memories of her kindly welcome in the generously untidy, yet methodical, book room of Time and Tide, and many owe their introduction into the world of literary journalism to one of the little luncheon parties she used to give at the now vanished Gourmets Restaurant".

Student Activities

References

(1) Catherine Clay, Theodora Bosanquet: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (8th September 2022)

(2) C. V. Wedgwood, The Times (3rd June 1961)

(3) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013) page 475

(4) Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work (2007) page 16

(5) Catherine Clay, Theodora Bosanquet: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (8th September 2022)

(6) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013) page 477

(7) Theodora Bosanquet, Harriet Martineau An Essay in Comprehension (1927) page 211

(8) David Doughan, Helen Archdale: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September, 2004)

(9) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013) page 335

(10) David Doughan, Helen Archdale: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September, 2004)

(11) Margaret Haig Thomas, letter to Helen Archdale (10th November, 1926)

(12) Margaret Haig Thomas, letter to Helen Archdale (October 1929)

(13) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013) page 341

(14) Theodora Bosanquet, diary entry (April, 1933)

(15) Catherine Clay, Theodora Bosanquet: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (8th September 2022)

(16) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013) page 481

(17) C. V. Wedgwood, The Times (3rd June 1961)

(18) Margaret Haig Thomas, letter to Winifred Holtby (23rd April 1933)

(19) Freya Stark, The Coast of Incense (1953) page 121

(20) Catherine Clay, Theodora Bosanquet: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (8th September 2022)

(21) Deirdre Beddoe, Margaret Haig Thomas : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (28th May 2015)

(22) Catherine Clay, Theodora Bosanquet: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (8th September 2022)