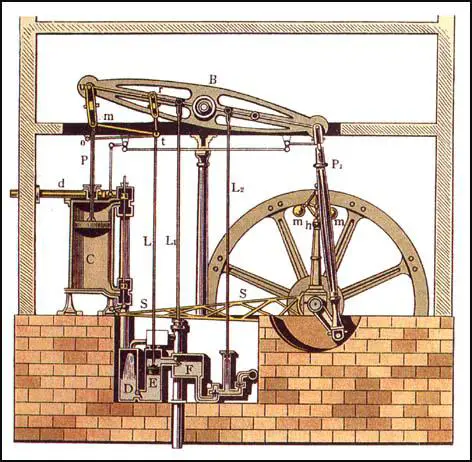

Rotaary Steam Engine

In 1763 James Watt was sent a Newcomen steam engine to repair. While putting it back into working order, Watt discovered how he could make the engine more efficient. Watt worked on the idea for several months and eventually produced a steam engine that cooled the used steam in a condenser separate from the main cylinder. Watt was not a wealthy man so he decided to seek a partner with money. John Roebuck, the owner of a Scottish ironworks, agreed to provide financial backing for the project.

When Roebuck went bankrupt in 1773, Watt took his ideas to Matthew Boulton, a successful businessman from Birmingham. For the next eleven years Boulton's factory was producing and selling Watt's steam-engines. These machines were mainly sold to colliery owners who used them to pump water from their mines. Watt's machine was very popular because it was four times more powerful than those that had been based on the Thomas Newcomen design.

One of Watt's steam-engines was purchased by John Wilkinson, who used it in his blast furnace. Wilkinson now helped Watt improve his steam-engine by developing a boring machine that was able to drill cylinders to a high standard of accuracy.

Watt continued to experiment and by 1782 had produced a rotary-motion steam engine. His machine now drove on both the forward and backward strokes of the piston, and a sun-and-planet gear produced rotary motion. Whereas his earlier machine, with its up-and-down pumping action, was ideal for draining mines, this new steam engine could be used to drive many different types of machinery. Richard Arkwright was quick to realise the importance of this new invention, and in 1783 he began using Watt's steam-engine in his textile mill. Others followed his lead and by 1800 there were over 500 of Watt's machines in Britain's mines and factories.

In 1755 Watt had been granted a patent by Parliament that prevented anybody else from making a steam-engine like the one he had developed. For the next twenty-five years, the Boulton & Watt company had a virtual monopoly over the production of steam-engines. Watt charged his customers a premium for using his steam engines. To justify this he compared his machine to a horse. Watt calculated that a horse exerted a pull of 180 lb., therefore, when he made a machine, he described its power in relation to a horse, i.e. "a 20 horse-power engine". Watt worked out how much each company saved by using his machine rather than a team of horses. The company then had to pay him one third of this figure every year, for the next twenty-five years.